I was wrong about the American Rescue Plan

Three cheers for the Great Rethink of macroconomic policy

This piece is written by Milan the Researcher, not the usual Matt-post.

Back in February of 2021, Matt wrote a piece titled “The $1.9 trillion relief plan is not too big.” His thesis was that the fiscal policy response to the Great Recession was too small, leading to a lost decade of high unemployment and weak growth, and that it was time to go big. Most people think of the 2019 economy as pretty good: the unemployment rate was 3.7%, inflation was 1.8%, and real wages were growing at 1.5%. But the experts at the Congressional Budget Office thought we were already running too hot. Remember all those 2019 articles about a looming recession?

Matt argued that “we were below potential in 2019 and […] the acceleration of job growth in early 2020 is strong evidence for that,” and so we should err on the side of overstimulating the economy in pursuit of true full employment.

One year and some change later, I published “The American Rescue Plan was too big.” My core argument was that Matt was wrong. ARP vastly overshot the output gap, despite warnings that the bill was too big prior to passage, and allocated the $1.9 trillion sub-optimally, including $350 billion to state and local governments that weren’t facing revenue shortfalls and $135 billion on an expanded Child Tax Credit which, while an excellent policy, lacked the votes to be made permanent.

At the time of that writing, inflation was running at 8.2% year-on-year, unemployment was at 3.6%, and real wages were shrinking at -2.5%. It seemed like we had over-learned from the last war and run right into the Phillips curve. I worried that this would discredit the emerging new consensus on macroeconomic management, even as structural problems (namely population aging) that the Great Rethink sought to address continued to cumulate.

Today, I am happy to say that I was wrong.

Smoothing over the pain

Conceptually, you can think of the question “How much stimulus should we do?” through the lens of pain distribution. When you have a global pandemic, some amount of economic harm is inevitable — the question is how best to manage it. Ideally, you would simply do the exact amount of stimulus required; in practice, you’re working with limited information and a lot of uncertainty and are subject to political constraints that may limit your first-best options. So you have a choice between erring on the side of doing too much or doing too little.

If you understimulate, that pain will be concentrated: you may have low inflation, but unemployment will be elevated. And when layoffs happen, the last people to be hired are going to be the first to be fired. They’re likely to be those already on the margins of society: Black workers, people with disabilities, ex-convicts, etc. If you overstimulate, the pain will be diffused: unemployment will be low but inflation will be higher. Instead of a few people losing all of their (labor) income, everyone takes a smaller haircut to their real wages.

In theory, that might make over-stimulation less popular, politically, than under-stimulation; instead of a small number of people upset that they lost their jobs, you have a large number upset about rising prices. (Comparing the results of the 2022 and 2010 midterm elections provides a point against this theory.) But from a utilitarian point of view, the latter is preferable. Because of the diminishing marginal utility of money, spreading out the pain does a better job of reducing aggregate harm.

Another advantage of going big is that it’s easier to correct a mistake. In 2009, the Obama team settled on asking Congress to pass $831 billion in stimulus, even though their economists’ calculated that the economy needed more like $1.7 or $1.8 trillion. The White House thought that moderate legislators would balk at that price tag and that if the ARRA money proved insufficient, they could just go back and ask Congress for more. Then Republicans won the House in 2010 and decided that they would strangle the recovery to try and deny Obama a second term, and that was the end of that.1 And the Fed had already cut rates to zero and was basically out of juice, so the country muddled through the next decade and it took almost 10 years for the labor market to recover.

That’s the risk of going too small on fiscal stimulus: a bad economy makes it very likely that the opposition wins control over some veto points, and it is in their political interest to sabotage the economy, pin the blame on the incumbent, and win the next election.2 But if you go too big on fiscal stimulus, the central bank can use monetary policy to correct the error; the institution is intentionally insulated from political pressure by structure, norms, and the opaque nature of the interest rate mechanism to the lay public.

On the American Rescue Plan, I stand by my critiques of two of the line items.

$350 billion on state and local government aid: By March of 2021, when ARP was being written and voted on, it was clear that state and local governments were not facing a revenue shortfall. This aid was economically unnecessary, ended up paying for counterproductive policies such as permanent state tax cuts, and should have been capped at replacing lost tax revenue.

$135 billion on the expanded CTC: Slow Boring has done a lot of coverage of the expansion of the Child Tax Credit. It’s a good policy, and I support making it permanent. But the political support for that just did not materialize; it seems like Joe Manchin understood the ARP’s expansion as a one-time, emergency measure, while the White House and most of the Democratic caucus intended it as a pilot for a permanent expansion. Given that the votes simply did not exist to make the policy permanent, I think that it would’ve been better to leave it out of the bill and use the money elsewhere.

Of course, there’s also the $410 billion spent on a final round of stimulus payments. My prior view was that the extra helicopter money was economically unnecessary, but if you clinch the Senate majority by promoting another round of checks, you can’t just turn around and not do it. But now I’m not so sure. Matt Klein pointed out that America’s weaker welfare state and a higher level of business destruction called for spending more money to aid the recovery.3 And the fact that we’re beating Europe on growth without notably higher inflation arguably proves that the third round of stimulus checks wasn’t excessive.

Siphoning supply from Europe

When America went big on stimulus, we went really big. Between the CARES Act, the stimulus tacked onto the December 2020 appropriations bill, and the ARP, Congress did about $5 trillion in fiscal stimulus.

Compared to European nations with stronger pre-existing welfare states who opted to give employers money to furlough workers, we provided much more in the way of direct cash transfers — most famously the stimulus checks but more significantly via a huge temporary boost to unemployment benefits.

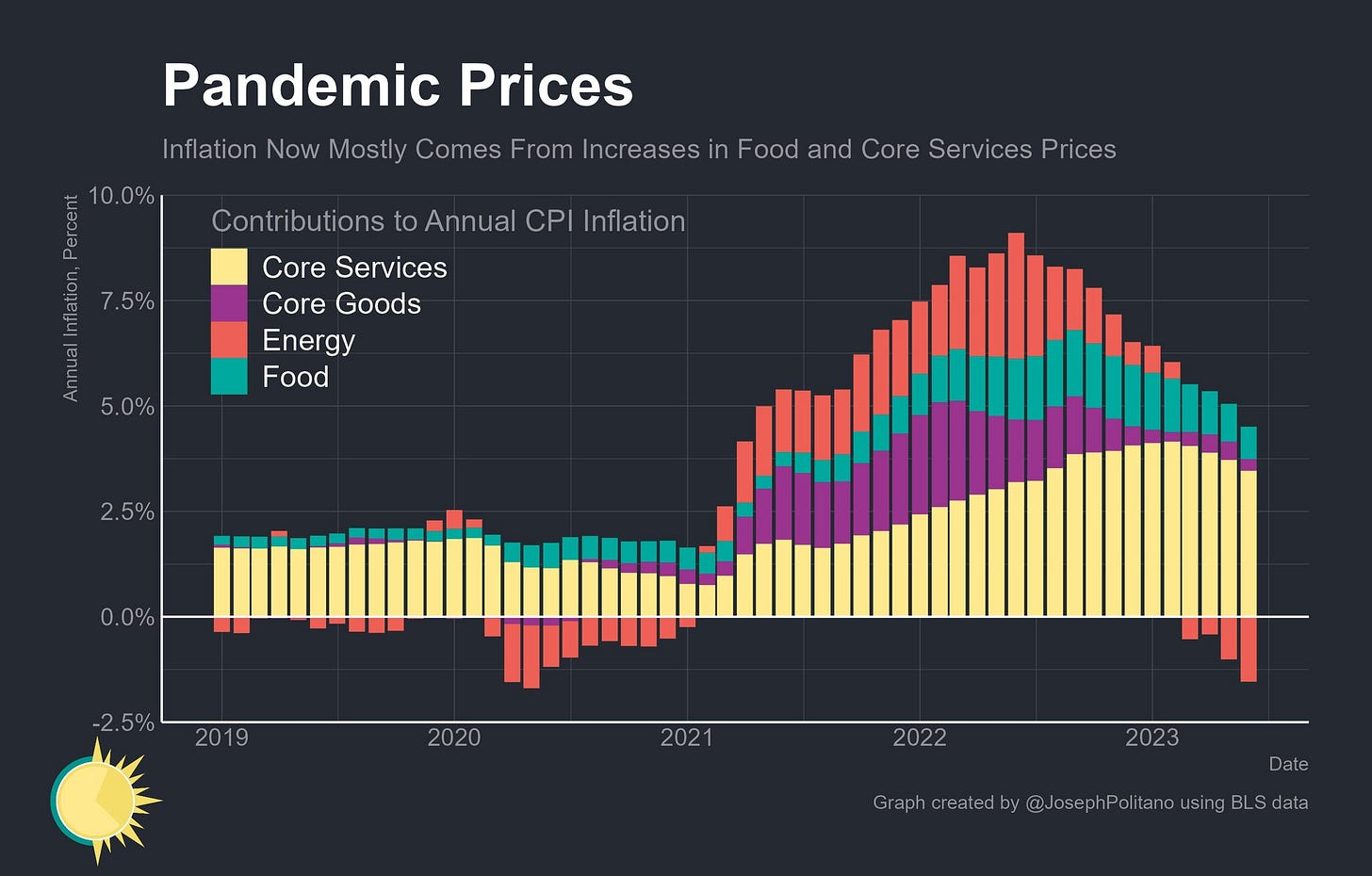

Without wading into the whole “Team Transitory vs. Team Permanent” debate, post-Covid inflation can be attributed to a combination of (1) pandemic-related supply constraints, (2) fiscal and monetary stimulus, and later (3) Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. One can debate the extent to which each factor contributed to the problem; I am not going to do that here. But Joey Politano pointed out to me that one effect of America spending much more than Europe, and especially much more on getting money into people’s pockets, was that American consumers were able to buy up a lot of goods during the 2021 reopening period. If you look at this chart shared by Dario Perkins, you see that the large majority of goods have been snatched up by Americans post-Covid.

That was good for American consumers — we got the goods we wanted at relatively cheap prices — but not so great for Europeans. They ended up with a much smaller supply of goods available for purchase and less money on hand with which to purchase them.

When you look at inflation in America, it’s mostly about the services; the rise in goods and energy prices have mostly worked their way out of the system.

Over in Europe, a big share of inflation has been energy prices, especially after Putin invaded Ukraine. Because of fracking and our abundance of natural gas, America simply wasn’t affected as much by the war; if anything, our plentiful reserves have helped us replace the gas that Europe used to import for Russia.

Today, the energy shock seems to have worked its way out of the system, but food and goods’ contribution to European inflation has been ticking up. Again, part of that likely comes down to Ukraine-related factors such as commodity shortages and the costs of replacing Russian gas in the food production supply chain. But some of the increase in European goods prices is likely down to America snatching up a lot of the supply earlier. That’s not great for Europe, but to the extent that American policymakers make decisions with the primary goal of benefitting American citizens, that’s a win for us.

The future is (still) Japanese

The failure to do enough in response to the Great Recession has been a disaster for the human race. Understimulating the economy left millions out of work, weakening demand and slowing economic growth. According to Matt Klein’s calculations, the consequence of undershooting stimulus was that “by the eve of the pandemic, U.S. output per person was 14% below where it would have been if the 1946-2006 trend had held steady,” which means that “the average American earned about $9,600 less in 2019 than would have been reasonably expected before the financial crisis.”

In America, we failed to do enough stimulus. But at least we were directionally correct — Europe has had it even worse because they responded to a shortfall in demand with fiscal austerity. For example, Greece’s economy still hasn’t fully recovered from the financial crisis. Absent the Great Recession, it should be richer than Poland; now it likely never will be. Globally — again, per Klein’s calculations — pre-pandemic economic output was running 12% below pre-financial crisis forecasts. That represents an enormous amount of lost human flourishing. And it was a completely avoidable and self-imposed outcome.

That very costly error rightfully spurred a rethink of macroeconomic policymaking. You can see the effects of that rethink in fiscal policy. (Joe Biden, February 5, 2021: “One thing we learned is, you know, we can’t do too much here; we can do too little. We can do too little and sputter.”) You can see it in monetary policy, in the Fed’s adoption of flexible average inflation targeting.4

But this rethink wasn’t just a response to the mistakes of the past, it’s a blueprint for the challenges that are coming. As I like to say, the future is Japanese. All around the world, populations are growing older, and that has some very important macroeconomic effects.

Older people need healthcare and pensions and, generally speaking, people don’t think it is right to force the elderly to work.

A smaller share of the population being of working age makes it harder to support the growing needs of the elderly; you either have to raise taxes or cut benefits or some combination of the two.

Because they don’t work, older people save more money than young people. Banks use the savings that people deposit to make loans;5 a greater supply of savings, therefore, reduces the price of borrowing — i.e., it pushes interest rates down.

Older people have a lower marginal propensity to consume.

An older population has lower productivity growth, and a slower-growing population drags on raw GDP growth.

What this all adds up to is a world of persistently weak demand leading to higher unemployment and weak inflation, as a symptom of an economy with too much slack and not enough growth. It’s a world where fiscal capacity is strained by providing for the elderly population and where low rates make it very difficult for central bankers to provide stimulus via monetary policy. Matt first wrote about this back in 2020, making the case for using massive fiscal stimulus to push long-term rates up and restore central banks’ ability to maneuver in the near future. (The return of actual fiscal constraints in budgeting has the added benefit of restoring sanity to politics by realigning disputes along a traditional left-right axis on economic issues.)

Nothing about the world’s long-term demographic trends has changed since the pandemic. But compared to our recovery from the last recession, we’ve done much better. It’s morning in America: unemployment is at 3.6%, inflation is at 3%, and real wages are growing at 1.3%. Compared to other rich nations, we’re doing much better on economic growth, while inflation has not been noticeably higher here than abroad — an important piece of evidence that the ARP did not actually overstimulate the economy.

That’s a victory for both Team Overshoot (we got full employment, while excess fiscal stimulus was canceled out by the Fed) and for the expectations view of monetary policy (the Federal Funds Rate has not risen nearly as fast as the Taylor rule says it should).

And it represents an important sign that this new approach can tackle secular stagnation: real 30-year yields on Treasury bonds are now sitting at around 1.5%, compared to around 1% pre-pandemic.

Klein told me that theoretically, long-term expectations for real rates shouldn’t be affected much by a one-off policy like the American Rescue Plan. But to the extent that markets viewed ARP as a blueprint for future policy, that pushed rate expectations up. If you look at the chart, you’ll notice that long-term rates spiked right after the Georgia runoffs were decided and markets expected lots of continued spending by a unified Democratic government, then fell during 2021 when it became clear that Biden lacked the votes to pass his original Build Back Better plan.

Perhaps ARP won’t become a blueprint for the future. The pandemic recession was unique in that Covid was not seen as the fault of anyone (in America), so it was easier to form a social and political consensus around going big on relief. That might not be the case next time, especially if ARP is looked back on as a mixed bag when the next recession hits.

But if the Great Rethink consensus sticks, and especially if future relief packages include automatic fiscal stabilizers, we will have effectively cured recessions. That could have its own unintended consequences — it could reduce creative destruction, or incentivize riskier behavior that requires even more costly cleanup. We can’t really know for sure. But given the risks of going too small, I think it’s worth a shot.

(Thank you to Joey Politano and Matt Klein for their help with this piece. You can find their work on Substack at Apricitas and The Overshoot, respectively.)

Mitch McConnell, October 24, 2010: “The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.”

It speaks volumes that House Republicans were willing to deliberately inflict economic harm on the American people to further their own electoral prospects, whereas when given the same opening in 2020, House Democrats put country over party.

Klein also told me that this made it easier to reallocate workers in the face of supply shortages, though that churn might have increased inflation in the short term.

I think that FAIT was originally intended as a soft lift of the inflation target from 2% to something like 2.5 or 3%. But the rapid spike in inflation post-pandemic forced the Fed to backpedal on that to retain credibility.

This is a somewhat simplified model of things, but for our purposes, it works.

Two weekend posts? Both excellent? Man, the value proposition of a Slow Boring subscription is insane. Seriously I think it’s the best of any media I purchase.

It’s nice to see a piece calling out where you went wrong in a previously published article and where you were on target. It often feels like so much of the discourse is people saying “that’s not what I meant!”. Meaning what you say and then being willing to correct it on the record is the mark of an honest person. Thanks Milan!