How banks create money out of nothing

The Fed’s two missions are intimately linked

In certain corners of the internet, you can get a good fight going by suggesting that banks, in the course of their normal banking activities, create money out thin air.

I think this notion is so contentious in part because it belongs to a strange class of ideas that are mostly articulated by cranks even though there’s nothing inherently cranky about them. It would be as if everybody was taught Newtonian mechanics in high school and college and discussed everyday phenomena in Newtonian terms, and the only people who ever mentioned relativity were political radicals who insisted that the constant speed of light shows we should do socialism.

The boring truth is that banks’ exogenous money creation does not have any particularly clear upshot for politics or policy.

But it’s interesting to consider, and I do think the standard account of banks collecting deposits and then loaning them out is an oversimplification we don’t need to maintain as our ultimate understanding of the financial world. And banks’ ability to create money helps explain the otherwise odd fact that the same institutions — the Fed, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, etc. — are charged with macroeconomic stabilization and with bank regulation. These are superficially very distinct functions. So much so that in the last financial policy overhaul, we formally created two different vice chairs of the Fed: one overseeing bank regulation and the other macro stabilization. But these things really are related, because banks create money so bank regulation and the money supply are interconnected. And you see that interconnection clearly at work this week as the Fed is on the one hand raising interest rates to slow demand and reduce inflation while on the other hand trying to prevent bank failures that they worry would slow inflation too much.

The mystery of money

As most parents of young children know, it’s surprisingly hard to say what money is exactly.

I’ve got some money (i.e., little pieces of paper) in my wallet, but most of my money is “money in the bank,” which is to say short-term loans to the bank. There are different kinds of short-term loans to the bank, though. I’m a normal person whose deposits are all FDIC-insured. But as we’ve been reminded recently, really rich people and, importantly, businesses can’t get by with only $250,000 in their account. So some money is insured and some is not, and there’s a difference. In addition to bank accounts, there are also money market funds, which are kind of like bank accounts but also kind of not. People sometimes say things like “I have most of my money in the stock market,” which usually means a majority of their net worth is composed of shares of stock, but shares of stock are not generally money — you can’t buy anything with them. When people say “Jeff Bezos made eleven zillion dollars last year,” they typically mean the value of his shares of Amazon stock went up.

“Elon Musk is worth over $150 billion” definitely does not mean that he has a giant vault full of money. It doesn’t even really mean that he could raise $150 billion by selling all the stock he owns, since if he suddenly started liquidating his whole stake in Tesla, the market would panic and the price would collapse. Words are just a little imprecise.

But generally speaking, money is what you use to buy things.

You can see the money-creation point if you think about something like a Home Equity Line of Credit. Let’s say you bought a house with a standard 20% downpayment and a 30-year loan 15 years ago. Today, after all those years of monthly payments, you’ve repaid a chunk of the principal on that loan. What’s more, the house is worth more than it was when you bought it. So the value of your home equity has risen over time and with it your net worth. But you can’t buy things with the unrealized value of your house. You have to sell it to get money, and then you can buy things. Alternatively, you can ask a bank for a loan that’s secured by the equity in your home. The way that works is the bank will put down in a spreadsheet “John owes us $X, with the loan secured by his home.” Then in another spreadsheet, they’ll put X additional dollars in John’s bank account.

When you get a loan like that from the bank, they don’t tell you “hang on for a couple of hours, we need to scrounge up some extra deposits before we can lend you the money.” In part because just like the deposits “in” the bank are, for the most part, not physically located anywhere, the expectation is that you’re not going to be getting your loan in the form of physical cash. These are all just spreadsheet entries. The bank goes from having no entries about you on their spreadsheets to having one entry about the money in your bank account and another entry about the money you owe them. The act of lending you the money created the bank deposits. And by taking out the loan, you transform yourself from being someone who has a lot of home equity but no money into someone who has a bunch of money but less home equity. You and the bank worked together to create money.

The golden age

It’s a kind of weird idea, but I think it makes sense if you turn the clock back and imagine a time when governments were minting coins out of precious metal. The old Spanish dollar that used to circulate throughout the Western Hemisphere, for example, was just a piece of silver — its value was derived from the value people placed on the silver itself.

The point of minting coins was the convenience of having standard quantities of precious metals to pass around rather than having everyone barter with randomly sized chips of silver and gold. Creating a coin with such-and-such silver content and stamping it in a recognizable way was a kind of public service, a little thing the government could do to grease the wheels of commerce.

That being said, carting around large amounts of metal can be an inconvenient way to handle transactions.

The word “bank” derives from the Italian word for “bench” because grain merchants would gather at benches to settle their accounts. It’s easier to write down numbers indicating who owes how much to whom than to keep passing big chests of coins back and forth. Eventually you get a system where the bench-based account keepers are setting up imposing-looking buildings of their own, often with vaults, where people can leave their precious metal for safekeeping. If you’ve got a bunch of metal in the bank, then the bank can write you a letter of credit — basically a promissory note saying “if you give this guy what he wants and he gives you the note, then you can take the note back to the bank and we’ll give you the metal.” That’s more convenient than dragging a bunch of metal out to wherever the deal was going to happen.

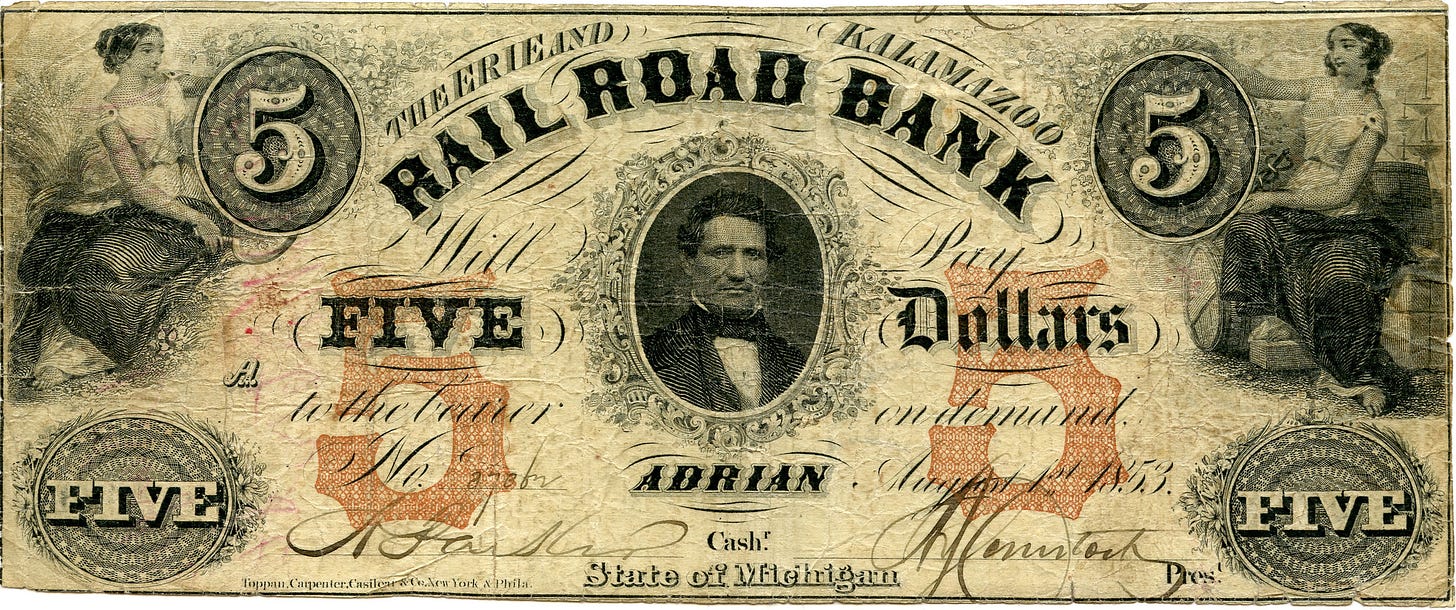

But it’s even simpler if nobody ever has to actually go to the bank and get the metal: I trade you some promissory notes for whatever you sell, and then you hand the promissory notes over to whomever you want to buy stuff from. The value of the promissory note is bound up in the idea that you could take it to the bank and get some gold. But in the ordinary course of things, the note itself is the thing people use as the medium of exchange. Eventually, instead of writing letters of credit to specific individuals, banks start issuing standardized promissory notes. Here’s a $5 bill from the Erie & Kalamazoo Railroad Bank:

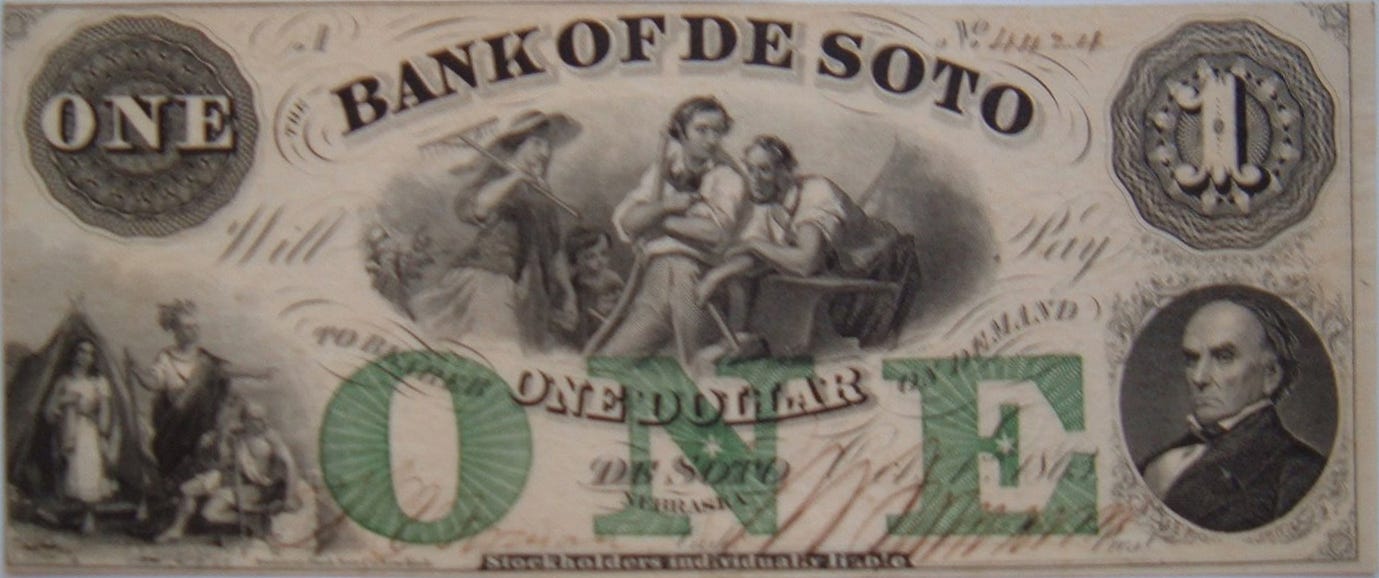

And here’s $1 from the Bank of De Soto:

In the pre-Civil War United States, that’s how it worked. The dollar was defined by the government as a quantity of gold, but most people kept their gold in the banks and used banknotes as money.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.