How fracking reshaped the world

Thanks, Obama

This piece is written by Milan the Researcher, not the usual Matt-post.

Sometimes I like to watch old clips of Barack Obama in my spare time, and the other day I came across this one where he takes credit for the boom in American oil production under his tenure.

The “Fox and Friends” hosts and their guest go on to complain about Obama’s regulatory policies, but they admit that oil and gas production did in fact go up during his presidency. Check the numbers from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, and you’ll see that Obama presided over a surge in natural gas and crude oil production, a decline in coal production, and the beginning of the wind and solar boom.

People don’t talk about this very much: Republicans don’t want to give Obama credit, and Democrats don’t often brag about increasing fossil fuel production. But the energy transition he oversaw has had significant and underrated impacts on the economy, the trajectory of climate change, and geopolitics.

A (very) brief history of fracking

Hydraulic fracturing has been around since 1949, but it took off during the Obama administration. This was partly because interest rates were near zero in the aftermath of the Great Recession, which made financing new fracking projects cheap, and partly because of technical advances. Oil companies figured out how to combine fracking with techniques such as horizontal drilling to tap into previously inaccessible reserves at affordable prices.

Here’s a somewhat simplified outline of the process:

You find a reserve of natural gas in shale rock.

You drill a hole, first going straight down, and then going horizontally once you hit the shale layer.

You mix up some chemicals and a bunch of water and inject it into the well you’ve made at high speed.

The pressure from the water and chemicals mixture causes the shale to crack — hence the name “hydraulic fracturing” — and release the natural gas.

The natural gas and the fracking fluid flow to the surface; you collect the gas and recycle the fluid.

There are some risks involved — the fluid might contaminate water supplies, and some of the methane in the natural gas might leak into the atmosphere.

Theoretically, groundwater contamination shouldn’t be a problem as long as you don’t screw up drilling the holes. (Several layers of rock separate the shale and the aquifers.) Environmental organizations like to argue that fracking still poses risks to water supplies, but trade groups say that the process is safe and there doesn’t seem to be a clear scientific consensus on this. Suffice it to say that fracking likely poses some increased risk to groundwater supplies. Another risk is surface water pollution: the used fracking fluid might not be properly stored and leak, or might not be properly treated.

Regarding air pollution, the big argument is that methane might leak into the atmosphere from fracking wells. If too much methane leaks, it might erase fracking’s climate advantage over coal. But the consensus estimate seems to be that the leaks are small enough that fracking is still better than coal from a climate perspective, and the main pro-fracking trade group is more-or-less on board with plans to reduce methane leakage.

A taste of energy abundance

One domestic consequence of the fracking boom was job creation. According to one study, fracking created 550,000 new jobs in the United States. The impact was not even: states with large shale reserves (such as North Dakota and Pennsylvania) added jobs, while those with a lot of coal (Kentucky and West Virginia) lost them. But in the aggregate, fracking was a net benefit to American employment. Research by Erin Mansur, Bruce Sacerdote, and James Feyrer concluded that “an increase of 725,000 jobs were associated with new oil and gas extraction between 2005 and 2012. Assuming no displacement from other employment, this suggests that the fracking boom lowered aggregate US unemployment by 0.5% during the Great Recession.”

A more plentiful supply of natural gas led to lower prices, which makes it easier to heat homes in places like New England where gas is used for that sort of thing. It made it more affordable for manufacturers to open new factories in states with large reserves. According to this 2015 Brookings white paper, the fracking boom reduced natural gas prices by $3.45 per 1,000 cubic feet, lowering residential electricity bills by $17 billion from 2007-2013 and saving the average gas-consuming household $200 per year. The authors also found that lower gas prices saved commercial buyers $11 billion over the same period, industrial buyers $22 billion, and electricity utilities $25 billion. (That’s a total increase of $74 billion to consumer surplus, offset by -$26 billion in producer surplus for a net gain of $48 billion.)

In other words, a surge in natural gas production gave America a sneak peek of what an energy abundance agenda has to offer. But by far the biggest impact of the fracking boom has been on renewable energy and the geopolitics of oil.

Natural gas and the rise of renewables

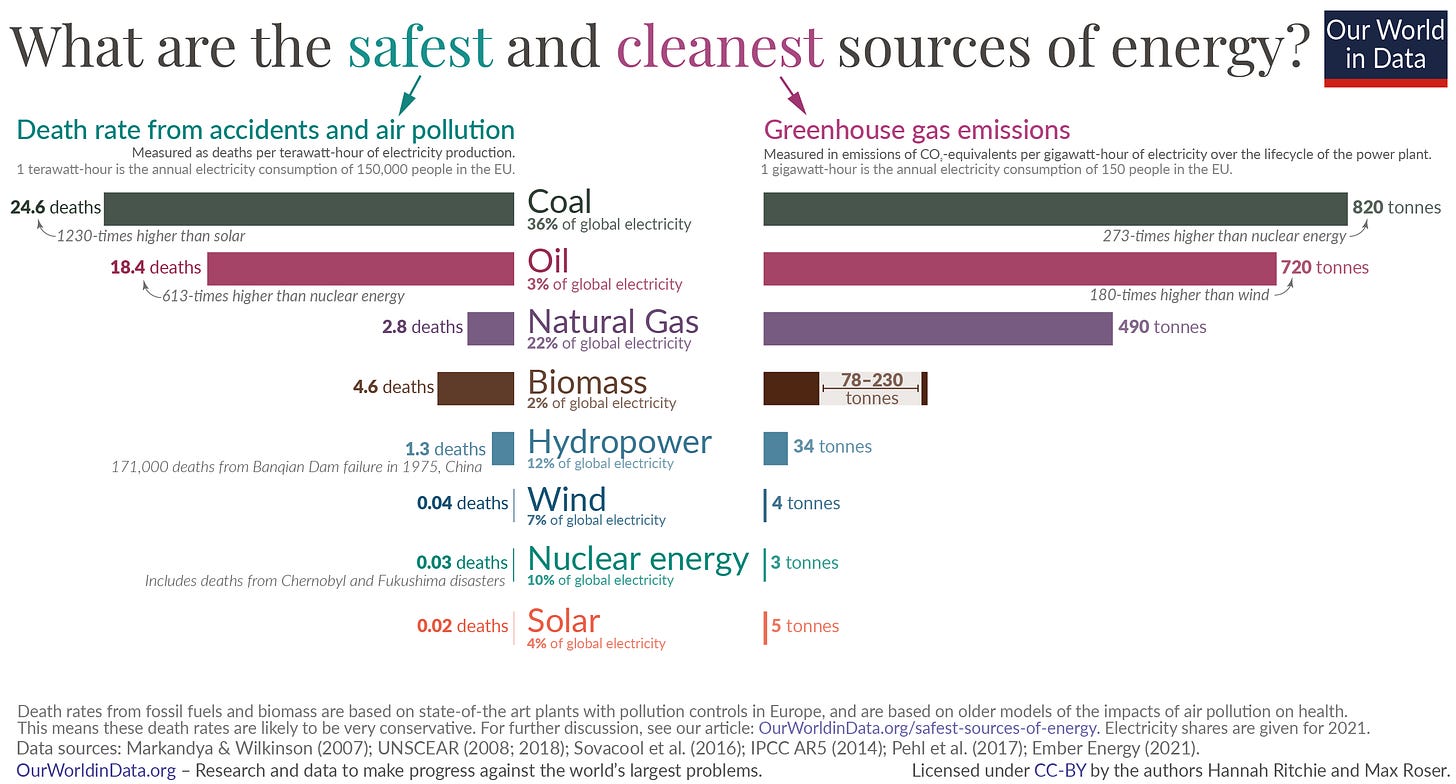

Air pollution is really bad. It’s so bad that the benefits of improving air quality alone would make the cost-benefit of decarbonization pencil out. It causes about 250,000 premature deaths in America, where we have relatively good air quality, annually. Globally, air pollution causes between four to seven million premature deaths every single year. It causes substantial non-lethal harm, including reductions in cognitive abilities and increased risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia. It can cause health problems in babies and young children. It’s bad for your lungs and it makes you feel like shit. And when it comes to air pollution, coal is by far the worst energy source on a per-unit basis, in both greenhouse gas emissions and deaths caused by accidents and air pollution.

The displacement of coal by fracking was a boon for both public health and for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Fracking made gas cheaper, which made coal relatively less appealing. As it happens, natural gas also turns out to be a very useful complement to wind and solar.

Way back in my first-grade days in 2009, Barack Obama and congressional Democrats passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. That law included $90 billion in funding for clean energy programs. Some of that money ended up going towards unsuccessful ventures; infamously, the program gave a $535 million loan to a solar power startup called Solyndra that ended up failing. Republicans used to make hay out of calling ARRA’s clean energy funding a wasteful government handout; in 2012, Mitt Romney was calling Tesla Motors a “loser” company. But in 2023, the conventional wisdom is that the ARRA investment in renewables successfully jumpstarted the modern wind and solar industries.

The ARRA money was important, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. Solar and wind are intermittent sources of energy; they can’t generate electricity when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing. If you wanted a 100%-renewable grid, you’d have to build out a ton of excess production (panels, turbines) and storage (batteries) capacity for cloudy and windless days. This is expensive and requires a lot of land. Alternatively, you can rely on a firm power source — some kind of power plant that you can turn on or off at a whim — as a backup. There are plenty of different kinds of firm energy — coal, nuclear, and hydro fit the bill — but in practice, the best complement for solar and wind is natural gas.

These days, renewables like wind and solar are cost-competitive with fossil fuels in many places. Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act allocated between $400 billion (according to the CBO) and $1.2 trillion (according to Goldman Sachs) of taxpayer money toward boosting clean energy. Government spending might drive another $3 trillion in private-sector investment. A lot of that money will end up going to red states with landscapes naturally suited to renewables, such as Wyoming (wind) and Texas (solar). This creates a political obstacle to greening America: Republican politicians tend to favor oil and gas and distrust or outright dislike wind and solar. In Texas, where clean energy now provides 25-30% of power, Republican legislators recently attempted to change the laws to make it harder to build new wind and solar projects and lost. Why? Because the numbers don’t lie — the green energy tax credits in the IRA are projected to create more than 100,000 new jobs in the state.

Besides permitting reform, the big barrier to renewable energy is that it takes up a lot of space. If we wanted to run the grid off of only renewables, America would need to use four times as much land as we do now to satisfy our energy needs. That’s because we’d need a lot of excess capacity to hedge against the intermittency of getting 98% of our power from wind and solar. With natural gas (and new nuclear plants and carbon capture technology1) as a backup, decarbonization becomes much less land-intensive: we’d need to use 200 million fewer acres compared to the pure-renewables scenario.

It’s the oil, stupid

Under Obama, fracking made America a net oil exporter, which has had important consequences for geopolitics. Take the Gulf states. Traditionally, America’s relationship with Saudi Arabia has, at its core, been about oil (though it’s considered bad form to make this connection explicit): Washington sells the kingdom American weapons and in exchange, Riyadh keeps the black stuff flowing.

Back when America was a net importer, this relationship worked out well for both parties. America really needed the oil, and Saudi Arabia really needed the weapons. Saudi Arabia also really needs oil revenue. The country is an absolute monarchy ruled by the House of Saud, and oil revenues finance the vast majority of its budget. The princes take a good chunk of that money and use it to buy yachts and fine art, but the implicit social contract is that in exchange for forfeiting civil liberties and democratic rights, Saudi citizens enjoy lifestyles heavily subsidized by oil revenue.

Lower oil prices are an existential threat to Saudi Arabia’s political economy — so the princes responded to the fracking boom by starting a price war. In 2014, the Saudis begin surging production, flooding the market with oil and pushing prices down in the hopes of driving American frackers out of business.2 In 2016, Russia joined OPEC+ and agreed to restrict production to drive oil prices back up. In 2020, the Saudis started a price war against Russia after the latter refused to agree to further cuts.

There are many reasons why the U.S.-Saudi relationship has soured. Tehran is the kingdom’s primary regional rival and Riyadh was not too pleased when Obama brokered the Iran nuclear deal. Joe Biden ran on a promise to make the kingdom a “pariah” state over Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s killing of Jamal Khashoggi and the war in Yemen (though he has tried to mend ties as president). MBS reportedly favors Donald Trump over Biden and may use oil production to help the former return to the White House in 2024; his investment fund gave Jared Kushner $2 billion. But the fracking boom opened a rift between Washington and Riyadh, creating room for MBS to forge closer ties with Russia and China. Zooming out, Washington is following through on Obama’s “pivot to Asia” and shifting its focus away from the Middle East and towards great power competition with Beijing. The relationship with Saudi Arabia is just less valuable for the U.S. than it used to be — not least because we don’t need their oil the way we used to.

Over in Europe, natural gas kept the EU dependent on Russian energy. Starting under Gerhard Schröder with the construction of the Nord Stream pipeline and continuing under Angela Merkel with Nord Stream 2, Germany phased out its nuclear power plants as it ramped up its reliance on imported Russian gas. Cheap natural gas spread Moscow’s soft power through things like soccer team sponsorships.

When Putin invaded Ukraine, a combination of EU sanctions and Russian cutoffs triggered an energy crisis on the continent. But America has very large reserves of natural gas and a lot of practice extracting it, which allowed Washington to step in and fill the gap. That might’ve made the difference between continued European support for Kyiv and capitulation.

None of this is to say that the oil doesn’t matter anymore — it absolutely does. Net exporter or not, the price of oil is set globally, and American voters don’t like it when gas prices go up (that’s one of the main reasons Biden has re-engaged with MBS). The fundamental change is that 50 years ago, we were a net importer of oil and our primary geopolitical rival, the Soviet Union, was a net exporter. During the Cold War, rising oil prices directly benefited Moscow and directly hurt us. Today, the situation is reversed: we’re a net exporter, and Beijing is a net importer. A negative oil supply shock still hurts the United States, but it isn’t the fatal blow that it used to be, and it arguably hurts our biggest rival more.

Here at Slow Boring, we donate 5% of revenue to Stripe Climate — subscribe to support the development of advanced carbon capture technology! (We also donate 10% to GiveWell’s Top Charities Fund.)

The fact that a lot of frackers lost their shirts in the price war is one reason that oil companies have been hesitant to invest in increased production over the last few years.

I could not be better targeted than I am by Slow Boring’s combination of obsessively pro growth politics and open Democratic partisanship

"This piece is written by Milan the Researcher, not the usual Matt-post."

CPI needs to track title inflation, how did intern become Researcher.