Two visions of environmentalism

A better world for people vs. a world with less human impact

Josh Lappen had an illuminating piece for Heatmap a few weeks ago forecasting increased tensions within the climate coalition around questions like permitting reform. The article focused on “three of the most important factions within the climate coalition — the environmental movement, the clean energy industry, and the Washington-centric group I’ve termed the green growthers.”

That interest group lens is a powerful one for examining these topics. There is, for example, an obvious alignment of interests between the solar power industry and environmental groups. But it’s a contingent alliance — if it turned out that actually solar panels cause a ton of pollution, the solar industry would still want people to buy solar panels while environmentalists wouldn’t. That’s not the case, of course, but it is true that from an industry perspective, a panel is a panel is a panel, whether it’s plastered atop a wildlife refuge or a scenic valley or an urban rooftop. Conversely, environmentalists care a lot about where things are built, but (contrary to a green growth view) often don’t care that much about whether or not anything actually gets built.

But Lappen’s taxonomy also suggests a more philosophical way of looking at these disagreements as reflecting two fundamentally different worldviews: a human-centered view of environmental problems versus a neopastoralist one that emphasizes the interests of nature as distinct from humanity.

These views will often coalesce around the same objective — the tremendous progress on cleaning up America’s rivers since the passage of the Clean Water Act has been a boon to wildlife and also made our cities more pleasant places. A river that’s healthy for fish and birds is also a recreational asset that’s clean enough for swimming and boating. But even though these are not completely disparate worldviews, they absolutely do at times press in different directions. Because while humans suffer adverse consequences from pollution, we also reap the upside of industrial civilization in a way that most animals do not.

Economic development is good

Bangladesh is a densely populated coastal nation whose population lives at very low altitudes, often near flood-prone rivers. Bangladesh is also fairly close to the equator and has a tropical climate. So in many ways, it offers a preview of the perils climate change poses for humans, as Somini Sengupta documented in late June for the New York Times. But Sengupta’s claim that “this matters to the rest of the world, because what the 170 million people of this crowded, low-lying delta nation face today is what many of us will face tomorrow” is a little bit slippery.

It’s true that many people around the world will, in the near future, face the sort of problems people in Bangladesh face today. But it’s probably not true that “many of us” in the audience of New York Times readers — overwhelmingly upscale residents of rich countries — will face these problems, because we are rich while many of Bangladesh’s problems are downstream of being poor. If you look at the world’s 10 most populous countries (the chart below is on a log scale), you can see that Bangladesh is not only dramatically poorer than the United States, but is also quite a bit poorer than Indonesia or China or Mexico.

An example of the overlap between humanistic and neopastoral views is that both see the historic legacy of carbon dioxide emissions from rich countries as a kind of world-historical injustice. The United States (and others) got rich in large part by burning fossil fuels, and now Bangladesh, which is not rich, is going to pay the price.

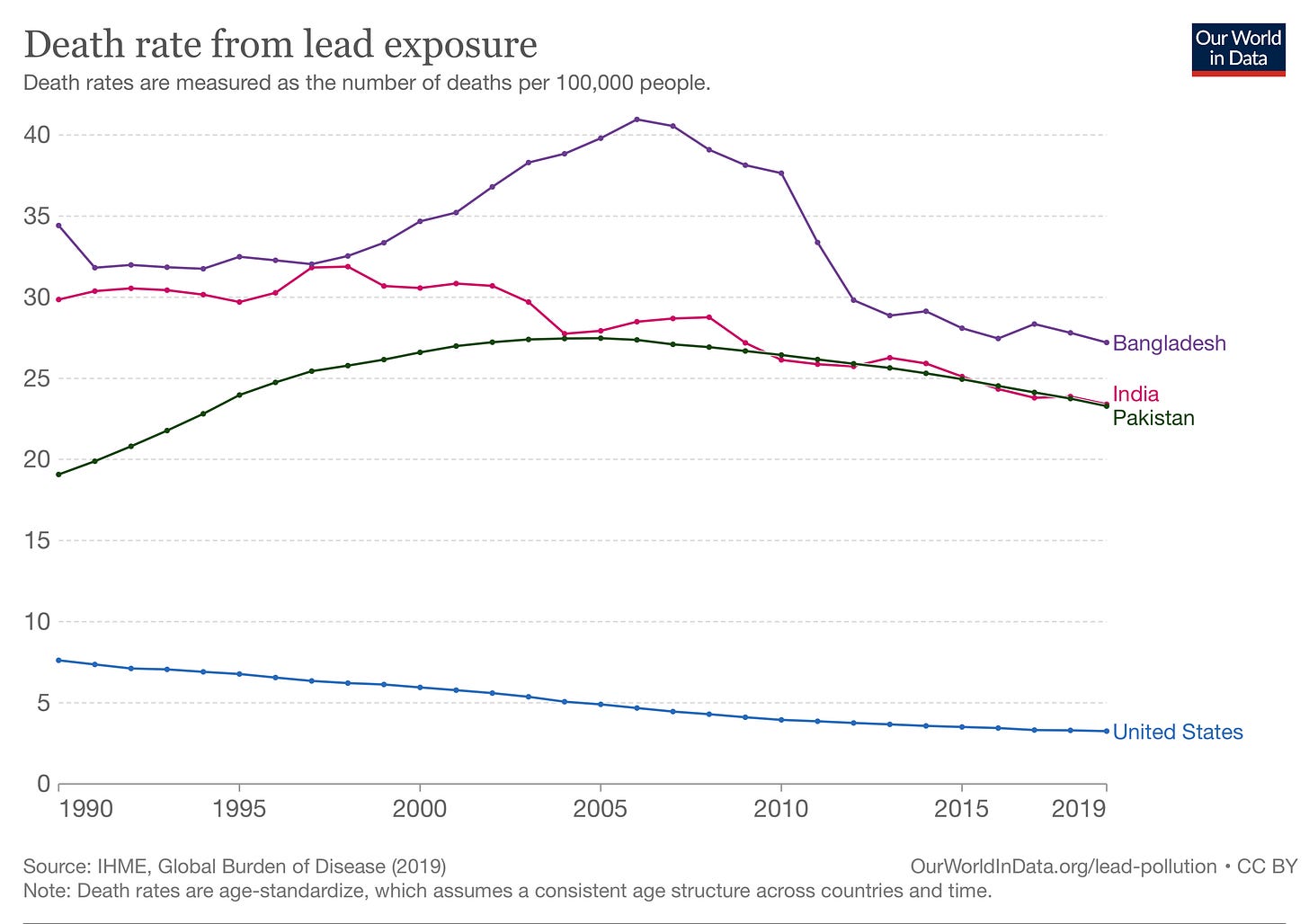

But these views provide contrasting perspectives on a question like, “what if India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh had grown rapidly as China since 1990?”

I think that would be great. A world in which the economics of South Asia grew as fast as China has grown would be a world with much less poverty and much greater human flourishing. It would be a world in which Africa was poised for an industrial takeoff as the last redoubt of truly cheap global labor in a world of higher consumer demand.

But rapid Chinese economic growth has undeniably pushed global greenhouse gas emissions up. And comparable growth in India/Pakistan/Bangladesh would have had an even larger impact since these countries, in aggregate, have more people than China. The more rapid warming of the planet would have considerable downsides for people in South Asia and elsewhere. But crucially, on net, people in Bangladesh would be better off with triple the income and bigger climate problems because they could invest in air conditioning, more productive agriculture, and better flood control.

The question of whether economic development is a good thing that has downsides or a bad thing reflects a fundamental divergence of worldviews. One suggests boring ideas like “price the externalities” and a focus on new technologies, rock weathering, carbon storage, nuclear energy, and — yes — permitting reform rather than emissions reductions by any means necessary. But the views also have different implications for the environmental issues you should spend your time worrying about.

There’s a huge global lead poisoning problem

The early days of the Biden administration featured a burst of activity around lead remediation, with a heavy focus on reducing the use of lead pipes in water distribution systems.

That particular issue drew attention after the events in Flint, Michigan, which were both serious public health problems on the merits and also had the kind of obscene, highly visible nature that attracts a lot of media attention. Historically, though, most lead contamination in the United States is due to gasoline and paint, with lead paint leaving an especially dire legacy in the form of chips and dust even though it’s been banned since 1978. And unlike gasoline, which has gone unleaded globally, lead paint is still used in dozens of countries around the world — primarily in Africa, where a huge share of the world’s children are born, but also in many Latin American countries, Indonesia, and Turkey.

To get a sense of the scale of the problem, at the peak of Flint’s water contamination, approximately 5% of children there had blood lead levels above the United States’ trigger threshold. Globally, one-third of children are above that level; in low- and middle-income countries, half of all children exceed the U.S. threshold.

This is, objectively, an enormous environmental problem with dire implications for human welfare. Very high levels of lead are, as you would assume, toxic to animals (especially birds), just as they are to humans. But what makes lead particularly damaging to human ecology is that it has significant negative impacts on cognition, which is uniquely important to humans.

The lead problem in developing countries is annoyingly diffuse — there’s the paint, there’s cosmetics (especially kohl), there’s glazed ceramics, poorly made aluminum cookware, and lead in turmeric and other spices. All of these problems impact people in the United States to an extent, but that’s usually in the form of hand-carried imports from abroad because we have a stronger regulatory framework here. Note that unlike burning gas to generate electricity, there’s no real economic upside to letting people put lead in their spices to make them look more brightly colored. But actually standing up a regulatory apparatus that can prevent it is really difficult.

A tougher nut to crack is the legitimate industrial use of lead in making lead-acid batteries (that’s your standard “car battery”). These batteries have a limited working life, at which point something has to be done with them. The correct thing to do is to recycle them safely in a well-regulated facility. But all across South Asia, lots of batteries are recycled in “informal” smelting operations — essentially open firepits — that expose their operators to tons of lead and also poison the nearby air and soil. The upshot is catastrophically high levels of lead exposure, which is lethal in its worst cases but has wide-ranging consequences for the region well short of death.

I don’t want to be a “nobody is talking about this” guy on the subject of lead. People are, in fact, talking about it. The Center for Global Development has a project on this, an organization called Pure Earth is very focused on lead, UNICEF knows all about the problem, and I attended a conference in June in D.C. where I learned a lot about this issue.

But one of the things I learned is that there’s very little philanthropic funding in this space compared to many other environmental topics — seemingly because, unlike climate change, it doesn’t also impact polar bears and other charismatic megafauna.

Climate policy for humans

The basic distinction here between environmentalism for people and environmentalism for nature winds up being important in lots of ways, but one that’s near and dear to my heart is immigration.

When I was working on “One Billion Americans,” I thought a lot about the arguments and evidence related to the impact of immigration on the wages and incomes of native-born Americans. I also thought a lot about the impact of higher population levels on transportation and housing infrastructure, two subjects that I love to write about. What I hadn’t really thought about until I started discussing the project with editors and then with sometimes-skeptical audiences was the idea that increasing immigration to the United States would be bad because it would raise global carbon dioxide emissions.

On one level, I don’t have a good answer to this objection — it is absolutely true that if someone comes from Haiti to the United States to work as a maid, her CO2 emissions are going to rise. And this is just as true of skilled workers. When Indian computer programmers get an H-1B visa to come work in the United States, their income rises by a factor of five or six. It’s challenging to see that kind of boost to your standard of living without increasing your carbon footprint.

But is this a good objection? We can’t allow immigration because it’s too beneficial to immigrants? I’m skeptical.

Contemporary environmental groups no longer do anti-immigration advocacy, and even though Paul Ehrlich continues to be cited respectfully on 60 Minutes, as best I can tell he’s walked away from things like advocating for coercive mass sterilization campaigns. But there’s a difference between dropping a policy as a matter of pragmatic coalition politics and abandoning the underlying ideas that led to that policy in the first place. And I think everything from the skewed perspective on economic development in South Asia to the local radio callers complaining about the climate impact of One Billion Americans to the permitting debate comes back to this philosophical difference. If you view pollution as a hazard to human health that needs to be set against the considerable benefits of energy abundance to human flourishing, then you are making decisions about things like Willow and the Mountain Valley Pipeline in a world of tradeoffs.

But if your concern really is primarily about biodiversity and nature, it’s easy to fall back on the idea that maybe we can all just get by with rooftop solar and perhaps some romantic ideas about sparing the third world from the scourge of industrialization.

Started to write a long comment but realized it boiled down to: well lots of people get into environmental activism because they really like animals and nature while not being particularly inclined to systematize their moral views.

Unsurprisingly that leads to people acting as if they value nature for nature's sake (beyond instrumental benefits of diversity, happiness and even animal pleasure). I don't think they really have coherent preferences here but rather are just doing what most ppl do and cheering what makes them feel good and booing what makes them feel bad.

Yeah, tradeoffs are hard, and some parts of the environmental movement are ascetics.

But if you're denying that there's some intrinsic value to biodiversity and nature, I think you might find that it's not just blue-state hippies that disagree with you on that one.