Biden made the right call on Willow

Stand with Alaska Natives and Alaska labor — drill, baby, drill

The Biden administration, and the Democratic Party more broadly, have gone to great lengths to prioritize taking action on climate change. Their main piece of partisan legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act, dedicated its largest pool of money to energy efficiency and zero-emissions energy production. But they also weaved climate goals into other bills that have passed — like the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act — and have incorporated climate elements into their executive actions and their international diplomacy.

But after some initial flirtations with this approach, what they have not done is tried to destroy the domestic fossil fuel industry.

I think this balanced approach is the right one. It reflects the kind of approach people normally expect to see from any administration on any topic. The Trump administration put a lot of emphasis on reducing irregular migration, especially at the southern border. But they didn’t reduce it to zero, and despite Trump’s various insane musings, they didn’t bomb Mexico or whatever in pursuit of that goal. Life is full of tradeoffs and competing priorities, and while reducing greenhouse gas emissions is important, it’s not the only important thing in life or the only relevant consideration when making policy. Unfortunately for Biden, this issue is highly polarized: the fossil fuel industry and its allies are uncompromising in wanting zero attention paid to climate change, while the climate movement is uncompromising in wanting zero fossil fuel use. Thus a president who has done more on the climate issue than on any other topic gets himself denounced by climate journalists and New York Times columnists as a “climate fuckboy” for being willing to make historic investments in emissions reduction while still approving things like the Willow project.

I think Biden made the right call on Willow. It annoys me when climate group leaders put forward the IRA as an example of how they know how to win, even as they themselves reject the IRA approach. But the actually existing Inflation Reduction Act energy provisions — an effort to achieve emissions reductions in a way that Joe Manchin can live with — represent a good approach. The administration is trying to advance global decarbonization at an acceptable price rather than obsessively pining for the destruction of the American fossil fuel industry.

Unfortunately, Biden’s approach to climate is so unfashionable that the Biden administration itself seems somewhat disinterested in defending its own position on Willow. But I liked his line in the State of the Union Address about how America still needs oil whether environmentalists want to admit it or not, and I think he should lean into that.

Climate harms are relative to baseline

Patrick Brown from the Breakthrough Institute wrote a piece last week complaining about the treatment of crop yields in the latest IPCC report. The report talks about warming reducing yields, but Brown feels they don’t make it clear that they are talking about reductions relative to a baseline that assumes growing crop yields, not an absolute decline in yields:

Yet despite clear historical trends, the IPCC discusses decreases in crop yields ad nauseum throughout the chapter. Herein lies the obscurantism. Although most readers will understand the word “decrease” to mean a decrease relative to today, the IPCC uses the word to mean a decrease relative to a hypothetical world without climate change. So crop yields can be projected to continue to increase overall, but still be said to decrease compared to a hypothetical world with no climate change but in which everything else is the same.

I’m not sure I agree that this is a legitimate complaint about the IPCC. This is often the way policy analysis works. When the Congressional Budget Office said it believed the Affordable Care Act would reduce employment by inducing more early retirements, people wrote headlines about how the CBO was projecting a reduction in the workforce if the law passed. But the CBO was not saying there would be fewer workers in 2023 than in 2012, they were saying there would be fewer workers in 2023 than there would have been absent the ACA making it easier to retire early. The IPCC does the exact same thing, and I don’t have a huge problem with it.

Except Brown is right that lots of people seem confused about this, so someone is doing something wrong.

Climate change was never my beat, but I read a lot of policy analysis reports and I always took it for granted that the IPCC was talking about climate damages relative to a baseline of global economic growth. When I started pitching “One Billion Americans” to publishers, it became clear to me that lots of educated liberals believed that the climate science consensus was that the future would likely be worse than the present in absolute terms. I don’t really know why people think this; it’s genuinely not what the reports say. But they do, and it’s clearly influential in shaping the thinking of a significant minority of the public.

But the difference is really important. The correct perspective on climate change means that reducing emissions is good, but you still have to check and see whether the specific emissions reduction you are proposing makes sense. It’s like any other environmental topic. It’s great that America’s lakes and rivers have gotten cleaner, and I’m glad to see more investment happening in this area. But if someone told me they wanted to spend $100 billion cleaning the Potomac River, I’d say that’s too much — a cleaner river would be nice, but there are a lot of nice things you could do with $100 billion.

In climate terms, I think the key point is that the costs involved in different emissions reduction plans are very different. Imagine a 20-degree night in Boston. You could reduce the city’s fossil fuel consumption by getting everyone to turn down the thermostat in their house from 72 degrees to 68 degrees. Alternatively, you could select a small minority of households at random and turn their heat off entirely. Assuming you picked an appropriate number of people for Option 2, you could achieve the exact same emissions reductions in both cases. But Option 1 would be a harmless inconvenience whereas Option 2 would get a bunch of people killed.

A high-cost way to cut emissions

The most cost-effective way to cut emissions is to support innovation and technology that, if it pays off, would have an outsized impact on global efforts to mitigate climate change.

And over the past 20 years, the U.S. and other foreign governments have accomplished a lot this way. The price of solar panels and wind turbines has tumbled. The price of batteries has fallen. Multiple companies make commercially viable electric cars, e-bikes, and other zero-emissions vehicles. Some of these are pure business success stories, but there’s been a big policy element. The Obama administration kept Tesla afloat in its early years and got denounced for its trouble by Mitt Romney, but I think the bet paid off. Obama-era policymaking also played a role in the solar panel price decline, though in this case, I think action by the Chinese and German governments was probably more important. The Inflation Reduction Act continues this legacy with measures to help spur the nuclear industry, tax credits available for geothermal power, and probably most important of all, a bunch of measures designed to subsidize exploratory work in decarbonizing industrial processes.

Beyond that, the most cost-effective thing you can do to cut emissions is to put a price on them. Pricing emissions encourages people and businesses to make low-cost reductions while continuing to make it feasible to keep using fossil fuels where they’re most valuable. The politics of carbon taxation are very tricky, but it’s worth keeping in mind as a policy option now that the macroeconomic situation warrants deficit reduction.

What the IRA does instead is subsidize low-carbon consumption, in part by subsidizing zero-emissions energy generation but also by directly providing tax credits for electric cars, heat pumps, induction stoves, and other zero-emissions technology. This is not quite as good, but it works pretty well.

Blocking new fossil fuel extraction projects also reduces emissions, and it does so through the same mechanism as a carbon tax: higher prices change consumer behavior.

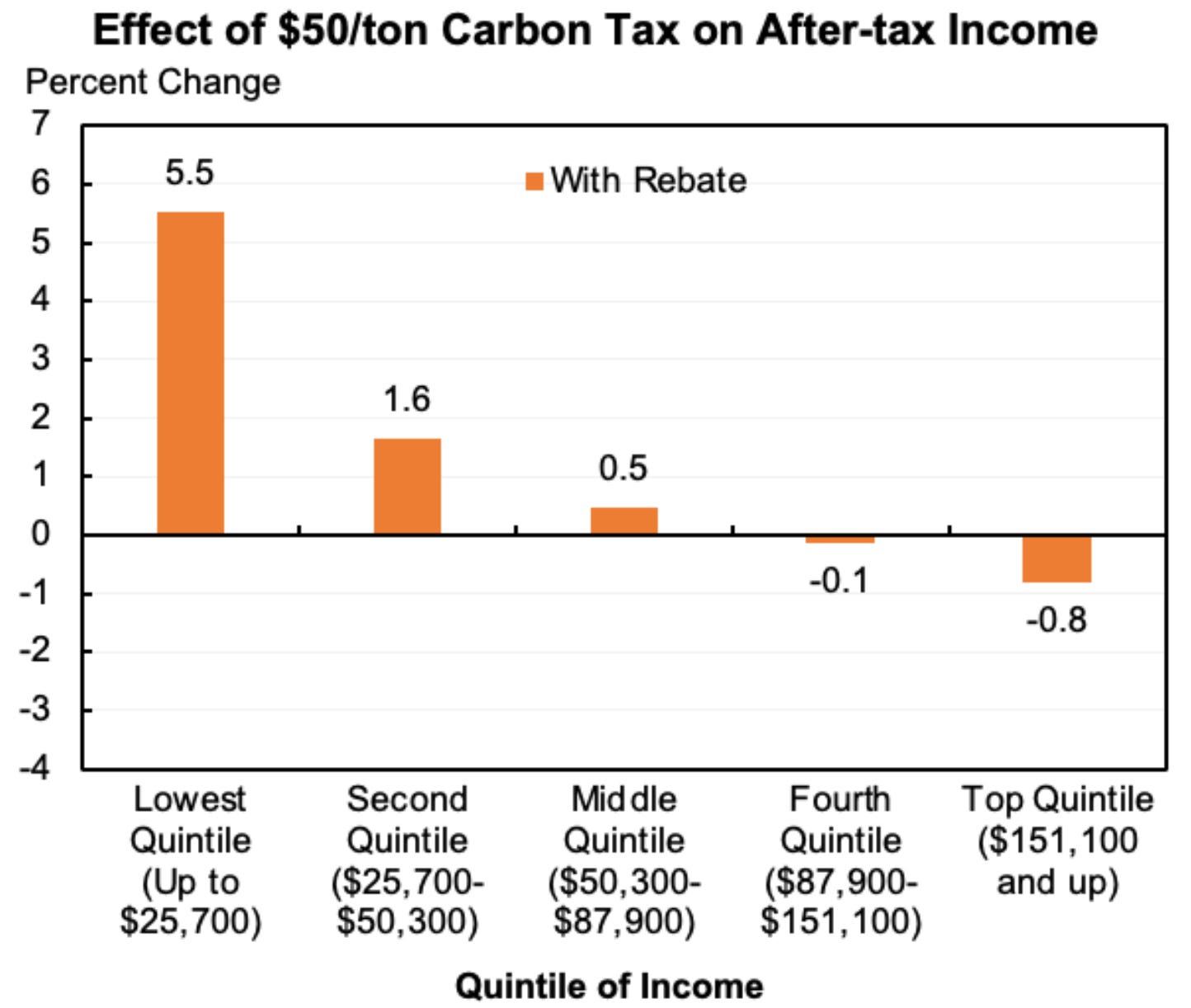

Because they have the same mechanism, they have the same major downside — people don’t like paying higher energy prices, and the impact of higher energy prices is regressive, falling harder on the poor than the rich. The difference, though, is that a carbon tax generates revenue that can be put to some useful purpose. You can, for example, use the carbon tax revenue to provide flat rebates which, as this Jason Furman chart shows, turns it into a progressive policy.

You could also do something else with the money, like avoid the need for Social Security cuts or reduce the deficit or fund green projects. The point is that revenue is useful.

Blocking fossil fuel projects, by contrast, raises costs for the poor without generating any revenue for the government. On the contrary, it costs the government revenue because fossil fuel companies pay taxes. Instead of the economic surplus from the $50/ton price increase flowing to Uncle Sam, it flows to other producers of oil who simply reap the windfall of higher prices. What’s particularly bad, though, is that because the price of oil is set globally, changes in domestic production have a very muted impact on global prices. Environmentalists themselves acknowledge this whenever someone suggests increased domestic production as a way to bring prices down. But it’s a perfectly symmetrical point. To generate the equivalent of a $50/ton increase in prices you need a gigantic cut in domestic production, because without demand-side measures, for every 10 barrels of oil you don’t drill at home, nine replacement barrels get drilled abroad.

This is why no successful center-left political movement in a place with fossil fuel reserves — not the Labor Party in Norway, not the SNP in Scotland, not the NDP in Alberta — adopts this approach to the climate issue. The local costs are just too wildly out of line with the benefits.

It matters what Alaskans think

Some people see “wokeness” as an incipient totalitarian trend on the left. But I think if you pay attention to energy politics, you’ll see that left-wing people are happy to blow off social justice precepts whenever it suits them. The Alaska Federation of Natives, for example, supports the Willow Project. Environmental groups reacted to indigenous support for the project not by deferring to marginalized people and frontline communities, but by backing a minority faction of Alaska Natives in suing against the project.

Meanwhile, Mary Peltola, a Yup’ik Democrat who managed to win the state’s at-large House seat, is a Willow supporter. And that’s no huge surprise since Willow is also backed by the Alaska AFL-CIO, as well as a bunch of national unions in the building trades.

If Alaska were a country the way Norway is, then Peltola would be the leader of its local center-left party with a social basis in the labor movement and indigenous communities. It would distinguish itself from a right-wing party’s approach to climate change by caring about things like science and technology and pricing, but not by trying to hammer the local fossil fuel industry. And the true spirit of the IRA was an appreciation on the part of Democrats that the United States is in fact a major fossil fuel-producing country and should address the climate issue in a way that is sensitive to the relevant economics. The real fuckboy move would have been for Biden to totally ignore Alaskan labor and kneecap his local political allies.

What’s a little bit infuriating about this is that when you look at how big climate groups run their messaging around the IRA, they all do a great job! They emphasize jobs and economic development and the idea that many of these programs will save consumers money. This is to say they know that hairshirt emissions politics and climate apocalypticism are losing messages. But you need to carry that analysis forward to things like Willow. There is no way to spin “blocking a fossil fuel project that is locally popular” as “good for jobs or economic development.” If the locals don’t want it, then fine, work with them to block it — oil extraction NIMBYism seems fine to me. But if they do want it, you have to let it go. If you’re a green group or a single-purpose climate advocate, I of course don’t expect you to applaud a new oil project. But you’ve also got to see that we’re living in the real world and that having Joe Biden — who made historic climate investments the centerpiece of his legislative agenda! — in office is very, very good for you. Clap for him, be happy, and let him try to steer the country through a difficult economic situation so he can run for re-election on prosperity and win.

A friend noted for me that the Cooperative Election Survey has a question asking if we should increase domestic fossil fuel production. Most people say yes, most independents say yes, and interestingly, most non-white Democrats say yes.

My very strong suspicion is that the racial divide among Democrats is just tracking socioeconomic issues. Black and Latin Democrats are poorer than white Democrats and less likely to have college degrees. They, like the Alaska Federation of Natives and the Alaska AFL-CIO, put more value on the economic upside of energy production. They are right to do so, and Biden is right to stand with them. I only wish he were unapologetic about it. Climate is a serious problem that is worthy of serious investments, and the Biden administration has made those investments. They ought to follow through with the regulatory changes needed to expand nuclear and geothermal power while addressing the interregional transmission lines that renewables need. But let the places with oil and gas keep drilling as long as it’s economically viable.

Manjoo's reaction does not make him look good, but it's just another entry in the eternal struggle between ineffective firebrands and effective incrementalists.

Everybody remembers the time that William Lloyd Garrison called Lincoln "the fuckboy of abolitionism".

I've asked this before, but I wonder how much oil America would import for every barrel it didn't produce? My strong suspicion is that it would be much closer to one barrel than zero barrels. Any reduction would simply be from the increased world price of oil from America producing less. If I'm right, it would be absolutely senseless for America to limit oil production, since it would have virtually no impact on climate change while inflicting huge damage on the US economy.

Also, 'we must do what [marginalised group of people] says we should do' has necessarily always meant 'we must do what a subgroup within [marginalised group of people] that has a position that aligns with mine says we should do'. Women disagree on abortion. Black people disagree on criminal justice. Native Alaskans disagree on oil production. Activists want to pretend the world is simple.