The good news on America's cleaner water

Things are improving, and recent legislation will make it even better

Oysters are returning to New York Harbor, and while the water is not yet clean enough to safely eat the oysters, their return is a double dose of good news about the quality of the water in the Hudson River.

On the one hand, the oysters went away because the water got too toxic, and it is now clean enough for them to survive. On the other hand, oysters are filter feeders, and their very presence helps clean up bodies of water. Their departure from the river was part of a downward spiral of ecological decay that has now been reversed. As a kid in the 1980s, I went to a summer camp that would send us occasionally to pitch in on early Hudson River cleanup efforts, and it’s good to know that’s bearing fruit.

Over the course of 2020 when everything was shut down, my son and I went a lot of hikes in the D.C. area. We were pleased to learn that water quality in the Potomac and Anacostia has been improving thanks in part to the efforts of teams of volunteer water-quality monitors and people pitching in to remove trash. Last fall, the city government announced an ambitious plan to dredge and cap significant stretches of contaminated sediment in both the Washington Channel and the Anacostia that should contribute to further improvements in quality.

It turns out, per an April Gallup survey, that the cleanliness of American water is the public’s top environmental concern. I think this is worth further discussion because it seems like an area of largely unheralded good news in which the New York and D.C. situations are fairly typical of the national average.

I think acknowledging this progress is important because the people who’ve done the work deserve credit. But also because I tend to agree with Hannah Ritchie that pessimism about environmental problems is paralyzing; it can induce despair in progressives who should be engaged and frighten moderates into believing that only extreme and unpalatable solutions will work. Improving America’s water hasn’t been easy or without cost, but it hasn’t been impossible or cost-prohibitive either — and there’s more we can do coming down the pike.

American water is getting cleaner

A lot of people know that the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland accumulated so much industrial waste that it caught fire in 1969, both because there’s now a Burning River brand of beer from the area and also because this is said to have been a precipitating event for the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. But the iconic photo of the burning river that ran in Time magazine was actually a photo of an older fire that happened in 1952. In fact, there were 11 significant Cuyahoga River fires prior to 1969, and the ‘69 one just became well-known because it intersected with a burgeoning political movement to do something about it.

But it’s also not like Cleveland was unique. There were fires in the Buffalo River and the Rouge River in the Detroit area.

Today, now that the rivers that feed the Great Lakes are not catching on fire, we can use more subtle gauges of pollution to assess the situation. And the trends are basically good. One major water hazard is a category of oily chemical called PCBs, and we can see that this type of pollution is improving along with a variety of measures, though we still have not quite hit our recommended targets.

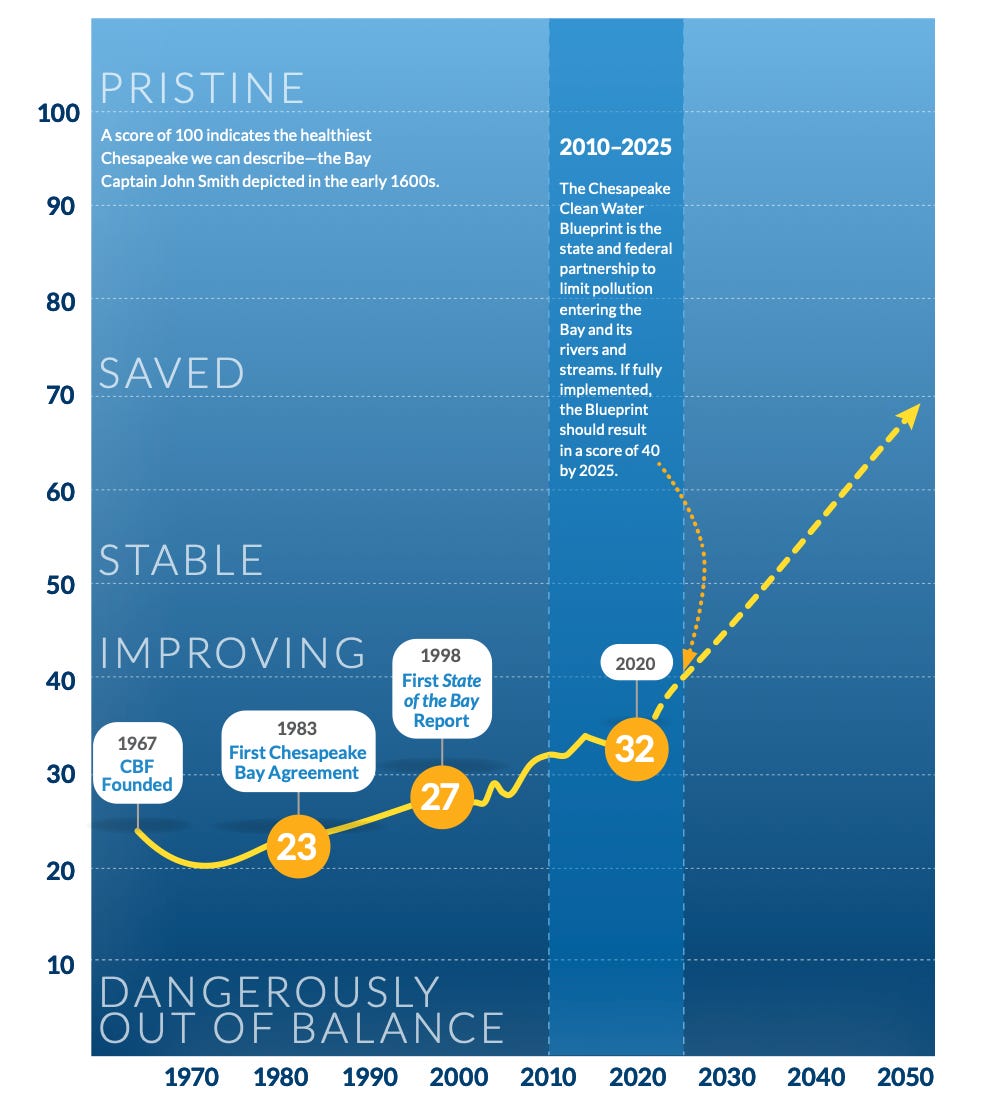

The Chesapeake Bay is also seeing reduced pollution levels (albeit fitfully) thanks to improved wastewater treatment.

The difficulty is that in most places, we have largely picked the lowest-hanging fruit in terms of regulating industrial runoff and upgrading water treatment. We’re now left with some mix of costly remediation efforts (which work but require money) and dealing with water runoff problems.

The hard problem of impermeable surfaces

When it rains in the woods, a lot of water is absorbed directly into the soil it lands on. Some pools up or runs into streams, but plenty goes straight into the ground.

On a paved road or a parking lot, that doesn’t happen. The surfaces are impermeable by water, so the water runs along until it eventually hits a drain. Here, two problems arise. One is that all kinds of oil, antifreeze, and other nasty stuff get picked up along the way. The other is that when the storm sewers are overloaded by water, they just dump a bunch of untreated, nasty water into the rivers.

Technologically speaking, this is a solvable problem. You can replace traditional asphalt parking lots with permeable pavers which massively reduce runoff, for example.

Back in 2012, then-governor of Maryland Martin O’Malley implemented a stormwater fee across the state’s non-rural jurisdictions. The idea was to both raise funds for stormwater remediation projects and also to incentivize the use of permeable surfaces rather than building more and more impermeable ones. It was a perfectly good idea, but unfortunately, it got demagogued as a “rain tax” and contributed to Larry Hogan winning the election in 2014. People hate taxes, so realistically it’s hard to get stuff like this done without bipartisan buy-in. But it was a good idea.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.