Russia's war on the world's food supply

It’s getting bad out there

Russia’s war in Ukraine is taking a terrible toll on Ukrainians and promoting hardship within Russia and throughout the developed world. But the biggest economic casualties are almost certainly the poorer countries that aren’t involved in the proxy conflict at all but are facing potential devastation due to the run-up in global food prices deliberately provoked by Russian policy.

Russia is using its Black Sea Fleet and control over most of Ukraine’s coastline to blockade exports of Ukrainian grain.

The grain can, to an extent, make its way to market along other routes. But back in 1843, the Russian Empire decided to build their railroad tracks a bit wider than standard gauge railroads.1 The Soviet Union continued this policy, and the result is that Ukrainian freight trains today can’t easily move into Poland, so the blockade creates a huge shipping bottleneck.

I initially assumed the Russians were primarily interested in hurting the Ukrainian economy by denying them export income and secondarily interested in raising global grain prices to benefit their own grain exporters. But Russia has halted grain exports and is now arguing that western countries should lift their sanctions on Russia in order to get the Russian grain flowing. This doesn’t make a lot of sense since the countries sanctioning Russia are not the countries most hurt by soaring food prices. Unfortunately, the whole idea of invading Ukraine didn’t make much sense either (I tried to warn them!), and Putin’s thinking on this issue seems driven by ideology rather than any practical consideration.

This leaves us with a really big problem, and its most straightforward solution — Turkey abrogates the Montreux Convention and NATO sends a fleet of warships to break the Russian blockade — involves gigantic downside risks.

Food has gotten very expensive

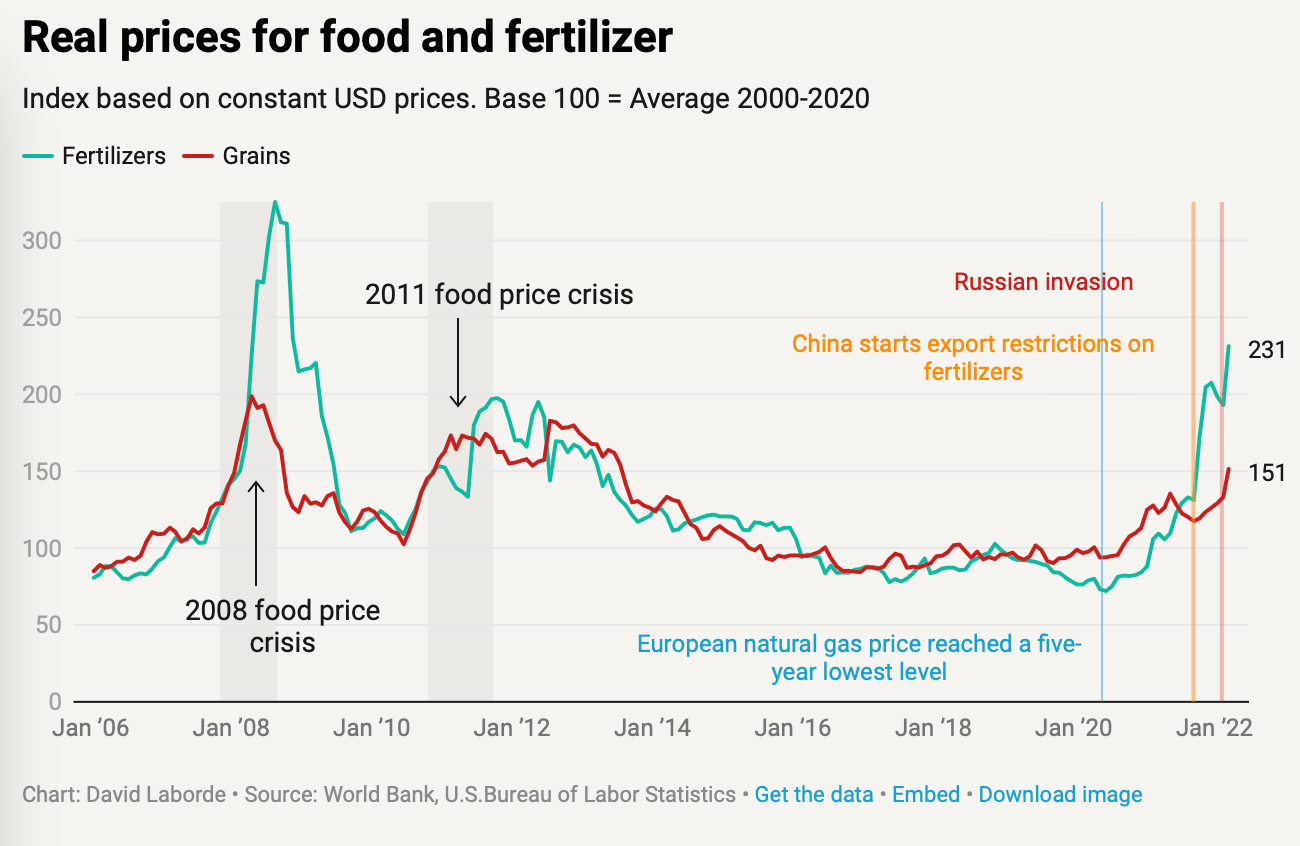

Today’s global inflation is partially attributable to stimulative fiscal and monetary policies enacted in a number of major countries, including notably the United States of America — you can see that clearly in the “core” Consumer Price Index that strips out volatile food and energy commodities. But these commodity price swings are very painful and as you can see, grocery prices have been rising in the United States faster than overall inflation, driven by a staggering 40 percent increase in the cost of wheat flour.

There is partial substitutability between different staple crops, so even though the blockade directly impacts the price of wheat, the price of corn is up 32 percent and the price of soybeans is up 18 percent. Grain costs also partially pass through into meat prices because they raise the cost of animal feed.

While expensive food is a genuine hardship to many people in rich countries, it’s not a crippling economic calamity the way expensive energy is. Back in 1970, the average American household spent 16 percent of its money on food; today we spend less than 8 percent, even as we’ve shifted to eating out more and eating more meat (and more food overall). Nobody is happy about rising food prices, but most households can adjust across many margins.

And even though very few Americans are farmers, our farmers have incredibly high productivity and the United States is a major global exporter of wheat. High wheat prices push up the value of the dollar, improve our terms of trade, and have some offsetting disinflationary benefits in terms of making exports cheaper.

Long story short, Russia’s wielding of the food weapon is certainly annoying to their antagonists in the U.S., Europe, and developed Asia. But the real pain is coming for countries that are totally uninvolved in the war.

Russia isn’t hurting their enemies

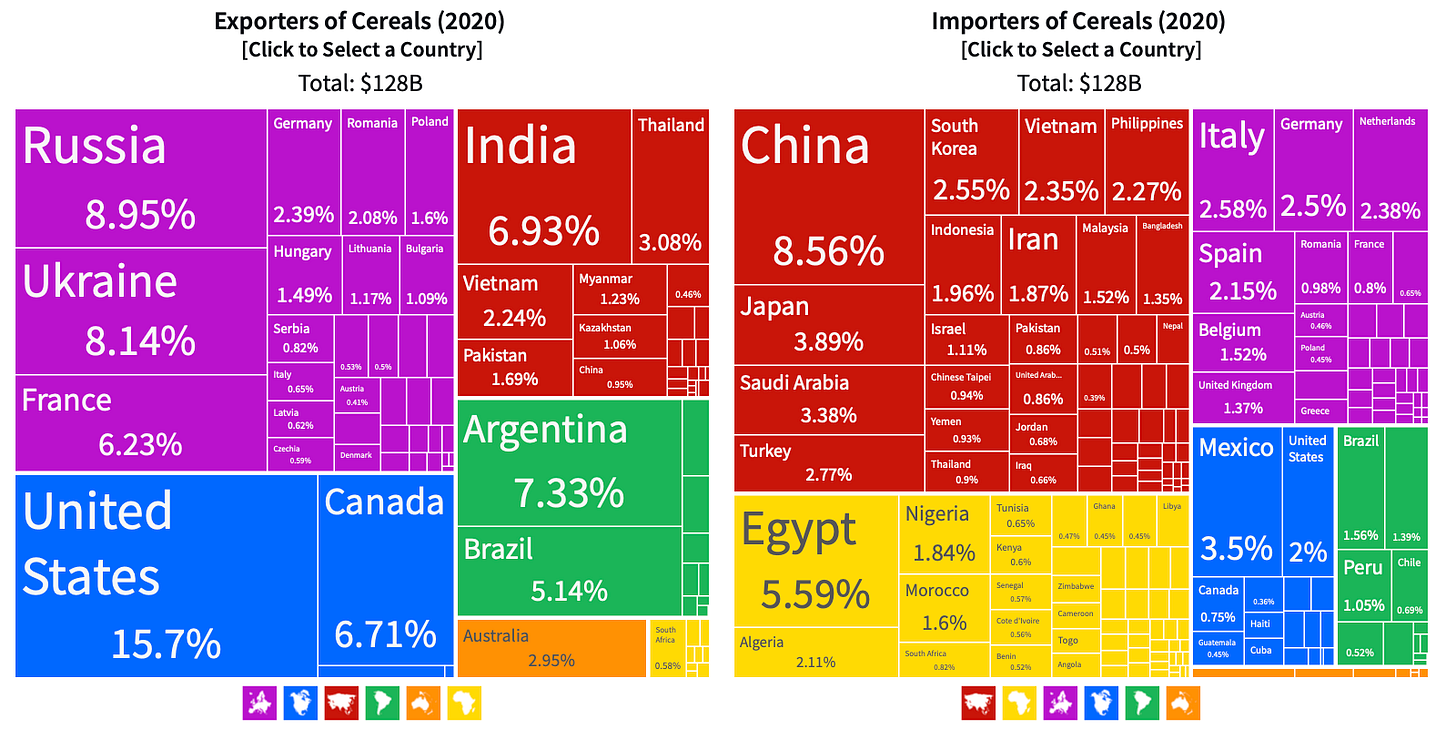

Russia and Ukraine are both huge wheat exporters. But as you can see the United States is also a huge wheat exporter, and the EU exports wheat, too. And the per-person wheat exports of Canada and Australia — also integral members of the anti-Russian sanction coalition — are positively gigantic.

By contrast, even the biggest net importers among the anti-Russian countries — Korea and Japan — don’t make the top 10 list, so the war on food is instead hammering countries like Egypt and Indonesia.

Before the war broke out, there was a sense that the European response to a Russian invasion might be muted by fear that Russia would respond to sanctions by cutting off energy exports. This has not happened. Instead, European leaders have faced pressure to cut off energy imports from Russia in order to deny Russia money and are now set to phase out oil imports, though not Russian natural gas.

But as Matt Klein emphasizes, the sanctions on Russia have been highly effective at limiting what they are able to import, so accumulating foreign currencies through exports isn’t actually that big of a deal for the Russian economy one way or the other. The point is that the food war is not particularly hurting Russia’s adversaries in this conflict. It’s not even hurting Ukraine that much because of the quantity of aid pouring into the country from the west. It’s true, of course, that Ukraine isn’t getting all the foreign weapons that they want. But this is a question of western governments’ policy choices, not of Ukraine needing more money through agricultural exports.

So while the Russian government would clearly like to exploit the havoc they are wreaking for gains in Ukraine, they have very little leverage. I’m sure Indonesia would gladly make big concessions to Russia in order to get them to lift the grain embargo, but Indonesia can’t do anything useful for Russia.

If you look more broadly at “cereals,” some European countries do take a hit, but plenty of others benefit from the grain shortage.

It’s a war, and blockading Ukraine’s sea exports is something Russia can do, so they are doing it. But the damage this does to the world is wildly out of proportion to the damage it does to Russia’s enemies.

A crisis for the global poor

I’ve only been looking at the country-level impact of food shortage. But living in a country that exports grain on net doesn’t mean that you personally will benefit from high grain prices.

India has a big albeit low-productivity agricultural sector, but it also has a large urban population that includes many poor people whose ability to feed themselves is badly imperiled by rising food prices — even rising prices improve India’s trade balance. Back in mid-May, the Indian government banned most wheat exports in an effort to insulate local food prices from global market trends, but while this move specifically helps poor people in India, it does nothing to alleviate the global shortage. All it really achieved was to set off a wave of country-specific food export bans that are disrupting global trade patterns and making food scarcer everywhere than it would be if nobody was doing this.

And it gets worse. The natural response to a bunch of grain coming off the market should be increased plantings elsewhere. But for a mix of reasons including high natural gas prices and the fact that Russia is a major producer, there is a simultaneous trend of soaring fertilizer prices that’s making it harder to generate new food supply.

There are also drought conditions in some relevant parts of the United States, further crimping supply.

The upshot is that food prices are likely to stay very elevated, creating a huge annoyance for rich country households. But those households are relatively unlikely to dramatically shrink their food consumption, which means it’s the global poor who are going to be left holding the bag in terms of actual trouble feeding themselves.

Here’s where I would like to have some great solutions

Unfortunately, I’m not sure I can offer great ideas about how to fix this.

It does underscore that seeing a Russia-Ukraine peace settlement would be highly desirable for the world. That’s a sentiment I often see accompanied by the assertion that there’s some “one weird trick” the United States could pull to end the war, which just doesn't seem true to me. Even the squishier European leaders like Olaf Scholz who are clearly uncomfortable with the concept of backing Ukraine in a fight to the finish aren’t coming back from their phone calls to Moscow with the outlines of what a settlement might look like. It’s good to continue to have dialogue, but as best as I can tell, the Russian invasion has from the start been motivated by some sincerely held and genuinely unreasonable ideas that are hard to compromise away.

I’m also worried about the precedent. The actual invasion of Ukraine has been very costly for Russia, and I think if a deal is reached at some point, it will be reasonable to think Russia has learned a lesson about the difficulties here. But the blockade gambit has been very low-cost for Russia, and as long as they retain the ability to do it, I’d be worried that they’ll just try again down the road.

In infrastructure terms, there are rail links between Ukraine and Poland that could take goods to Polish ports. The gauge incompatibility is an issue, but you could build a dry port with the fixed infrastructure to load and unload large numbers of containers off of one set of rail cars and onto another. The problem, according to the freight trade press, is that investors expect the war will end and the sea route will reopen, so you’d be undertaking a very expensive investment and potentially not be able to recoup it. The good news is that it seems like western governments could make this happen with a loan guarantee. The bigger problem is that even with the bad rail link, Polish ports are running out of capacity.

So the best strategy is probably to defeat Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. Ukraine got its hands on some Harpoon anti-ship missiles last week (and Sweden is about to send more), which should make defending Odesa against Russian attacks easier. And Turkey has closed the straits so Russia can’t re-enforce its naval force. But even though this will force Russian ships away from Ukraine’s remaining port, they could still linger out of range elsewhere in the Black Sea and probably maintain the blockade. The latest thing, as I understand it, is a Norwegian-made missile system called Naval Strike that lives on ships. Right now the U.S., Poland, and Norway are the only countries that have these (more are on the list), and either we could give some to Ukraine or else have the Poles do it and then backfill them. But you’d have to look at whether there are any vessels available to Ukraine that would be suitable.

There is something odd about the conventions governing this war where NATO giving Ukraine weapons to fire at Russia is considered fair game but NATO forces actually firing the weapons ourselves would be a potential trigger for nuclear war. But those are the rules we’re living with.

China’s mystery food stockpile

Finally, China has for slightly mysterious reasons stockpiled a staggering quantity of grain over the years.

The country has also taken a fairly pro-Russia line during the conflict, so of course they’re not eager to help the west out with a release of the wheat reserve.

But at the same time, it’s not really the U.S. or Europe who is suffering as a result of this food crunch. If Egypt and Indonesia and Nigeria and other places are pushed into crises as a result of a conflict between Russia and the West, it seems like a golden opportunity for China to trade its surplus grain for whatever geopolitical advantages they are interested in. So far, though, they haven’t done anything visible at all.

Will they start selling grain onto the open market at some point and reap a huge profit? That seems a little out of character, but it would be a great investment. Will they pull off some diplomatic masterstroke in Africa and the Middle East? Can the West accomplish something in bilateral talks with the Chinese on this topic? I don’t know and it seems like nobody else does either. The conventions of journalism are bad at underscoring the significance of the known-unknowns here. But we have a conflict between two major powers that is causing a huge global grain shortage and a third major power that has been stockpiling grain. You have to think that at some point, China will put that stockpile to use.

Many people say they made this choice to make it harder for Germans to invade, but the people saying this tend not to have any primary sources to cite. In an old Slavic Review article, R.M. Haywood says this is wrong and the Russians preferred it for technical reasons and simply thought the idea of a rail connection to the West was unrealistic.

I was with you right up until this:

“There is something odd about the conventions governing this war where NATO giving Ukraine weapons to fire at Russia is considered fair game but NATO forces actually firing the weapons ourselves would be a potential trigger for nuclear war.”

What’s odd? This is literally how proxy wars have worked since the days of the Roman Republic, if not before.

I assume that Putin is hoping to rerun his play with Syria:

commit atrocities and cause famine in third world;

create waves of desperate refugees flooding western democracies;

fund white supremacist/nativist candidates in the democracies;

see his puppets propelled to electoral victory by resentment of refugees and white supremacist hysteria;

watch his puppets relax sanctions and grant him territorial gains.

It's not crazy, it's just immoral. And with Murdoch, Le Pen, Farage, AfD, Trump, and lots of others working in concert, it has a good shot at succeeding.