How to promote growth and equality without raising taxes

Fixing the leaky buckets of upward redistribution

When I thought Democrats were going to lose the Senate, my planned post-election article was going to include a section on how the party needs to think more seriously about ways to generate broadly shared prosperity that aren’t just expansion of the welfare state.

The results are in, and I think it’s fair to say that Democrats basically won the midterms.

They did lose the House, though, and with it any hope of reviving the Build Back Better plan in the medium term. But even beyond that, I don’t think it makes a ton of sense in the current macroeconomic situation to center an economic message on welfare state expansion. Fundamentally, we are due for a deficit reduction cycle in which the right will say we should cut spending and the left will say we should raise taxes. The idea that taxing the rich needs to be part of fiscal responsibility is a classic Clinton/Obama message that still works for the Biden era. And that dynamic makes large welfare state expansions hard.

But it shouldn’t mean giving up on ideas to boost broad-based prosperity. It does mean Democrats need to look for egalitarian economic policy ideas that don’t require much if any tax revenue. And the good news is there are plenty of ideas like that.

The leaky bucket of upward redistribution

In 1975, Arthur Okun published his classic book “Equality and Efficiency: The Big Tradeoff,” the thesis of which is admirably clear from the title.

That book introduces a metaphor that I love. Redistribution, Okun says, is a leaky bucket, and efforts to take from A and give to B work, but they end up reducing the sum of A+B. Milan offered a great illustrative example of price controls for chicken sandwiches in his deadweight loss post: a rule that limits producers’ profits can generate gains for consumers, but overall welfare is reduced as fewer chicken sandwiches are sold.1

But where I think Okun goes awry is in assuming that all leaky buckets are examples of this tradeoff — as if anyone naively believes that the only thing the government could possibly do wrong is care too much about poor people.

There’s a certain type of economist who loves to dazzle people with examples of unintended consequences or how well-meaning policies go awry and cause harm. But the fact of the matter is that lots of policies we have in place are not well-intentioned at all. And their consequences aren’t unintended, they’re just bad. I think we should actually expect naked rent-seeking to be the primary source of inefficiency in the economy, not efforts at reducing inequality.

Part of what makes this rent-seeking so bad is that Okun is absolutely right about the leaky bucket (see this post on why parking regulations make it hard to unleash the power of technological innovation in the transportation sector). Nevertheless, it’s not hard to see why these rules are in place. Most people are happy with the parking situation that they have, so if you tell them we’re going to make changes that potentially involve them losing parking spaces, and we’re going to do that for the sake of Uber drivers, e-bike weirdos, and people so poor they’re stuck riding the bus, then that sounds like a loser of a reform even if the distributional impact is technically progressive. It’s important to help people understand that when a city does what Nashville just did and rolls back parking requirements, this contributes in subtle ways to widespread economic gains across the city.

It’s impossible to guarantee that policy reforms will make literally everyone better off,2 but you can focus on reforms that have two characteristics. One is that the number of winners exceeds the number of losers. And the other is that the surface-level distributive impact is both broad-based and progressive — you shouldn't rely on hypothetical redistribution to protect the interests of lower-income people.

The important case of housing

As Milan’s post argued, housing is an important example of this. Renters are poorer on average than homeowners, so policies restricting housing supply are an upward transfer from housing consumers (renters) to housing producers (landlords and homeowners), which is bad. How did this happen? Well, it’s not an unintended consequence of a well-meaning policy. The origin of American zoning is largely in efforts to uphold racial segregation. The Supreme Court struck down racial zoning laws decades before the Civil Rights Act, and by the 1960s, cities already had a well-entrenched practice of using zoning codes to promote economic segregation. And zoning became stricter in the decades following the Civil Rights Act when de jure racial segregation went out the window more generally.

Be that as it may, I don’t think running a white guilt play really convinces people to upzone. And the raw political fact is that homeowners are a majority of the population, and because we are older and richer than renters, we are an even larger majority of the electorate. Because we are less transient, we are also more likely to understand our local political system, be in touch with elected officials, and generally work the levers of power.

This is just to say that while redistribution from homeowners to renters is good egalitarianism, it’s bad politics. The promise of YIMBYism is that it isn’t just some sob story about renters; it’s also pro-growth reform that Republicans like Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin can support.

Or looked at the other way, it’s not just some pro-growth neoliberal deregulation that benefits homebuilders, but it’s also a critical means of addressing the cost of living faced by the poor, which makes it something the bleeding hearts at the National Low Income Housing Coalition can endorse.

Many homeowners will actually see the value of the land they own rise, even as the price of housing falls. Other homeowners will benefit from cheaper housing by being able to move into a larger place — especially in high-cost jurisdictions, it’s not only renters who end up fleeing in search of more square footage for growing families.

But housing is such a large part of the economy that housing reform isn’t just about housing. Public sector workers benefit from the growth of the tax base. Everyone who provides locally focused services — food service and retail workers, doctors and dentists, store owners, personal trainers, hairstylists — benefits from a growing customer base. Any reform you make is bound to be controversial. But that’s why it’s a good idea to look at the really large economic sectors where the gains are big.

Health care is full of supply constraints

Next to the housing/transportation complex, the biggest cost center facing American households is health care. And while there is a lot to say about policies related to the health insurance system and the distribution of payments for health care services, there are also a lot of policy ideas that would unlock efficiencies mostly at the expense of well-compensated providers.

A longstanding proposal from economist Dean Baker is to eliminate the rule that foreign-trained doctors must complete a U.S. residency program before practicing in the United States. If you or a loved one got sick in Lithuania, you probably wouldn’t feel any profound doubts about a Lithuanian doctor’s ability to treat you. Even without any specific information about Lithuanian medical training rules or EU regulatory standards, most of us would assume that whatever’s going on there is probably okay.

The standard for practicing medicine in the United States should be stricter than the “eh, it’s probably fine” standard we use while traveling, but much more liberal than the current rule. We should have an objective training and licensing standard that can be met by residents of any country — Lithuania or Mexico or Bangladesh or Nigeria — who are then allowed to come to the United States and work. That’s how free trade in goods works. Importing children’s toys isn’t a deregulated free for all, but the rule is that if a toy complies with Consumer Product Safety Commission rules then it can be made in China or Vietnam or wherever.

Medical training should work the same way. This would reduce doctors’ income, but grow real wages for the majority of Americans.

The pro-growth impacts would also generate additional revenue that could be used to increase the number of residency slots and train more U.S.-born doctors. And it’s not like doctors would be impoverished by this system. The most natural impact of a more abundant medical supply would be for providers to flow to places where doctors are currently scarce, for more people to offer off-hours work, for more entrepreneurs to offer high-end concierge services, and to otherwise actually grow the pie of medical care. It is a transfer from doctors to patients, but it’s not just a transfer.

The same logic could be applied to dentists. And also to scope-of-practice rules that make it hard for dental hygienists to clean dead teeth without working for a dentist and to rules that make it hard for a nurse practitioner to provide routine medical care services. These are all ideas that would build a more egalitarian, more prosperous economy without increases in taxes or explicit welfare payments.

Build more stuff in America

Whenever Democrats test inflation-related campaign messages, they hear that voters like the idea of strengthening domestic supply chains and increasing domestic production. John Fetterman’s campaign, which both progressive and moderate factionalists seem to agree was good, talked a lot about how he wants to “make more shit in America.”

It’s great that people like this slogan, and its popularity raises the question of what kind of policy would operationalize it.

One possibility is that “make more shit in America” means traditional trade protection — tariffs on imported Korean washing machines and imported Mexican car parts. The problem with those policy ideas is that whether voters like the slogan or not, those taxes make inflation worse rather than better. But it’s a genuinely ambiguous slogan, and there are lots of things you could do under the heading of “make more shit in America.” I would suggest the following as essentially a follow-up list for the Inflation Reduction Act:

Ease permitting for intra-regional electrical transmission lines so we can move wind and solar power from the places that are windy and sunny to the places where there is demand.

Get the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to promulgate rules for small modular reactors that account for the health and safety benefits of burning fewer fossil fuels and not just for the downside risk.

Give geothermal exploration projects on federal land the same categorical NEPA exemption enjoyed by oil and gas projects.

Create a permitting framework for hydrogen and CO2 pipelines to promote industrial decarbonization.

IRA has money for carbon capture projects, but right now the EPA isn’t authorizing any carbon storage wells, so the captured carbon mostly goes to enhanced oil recovery.

Most radically of all, I think the Biden administration should prioritize removing barriers to deploying zero-carbon energy over creating barriers to fossil fuels. We should have faith in the decarbonization potential of electrifying buildings and vehicles,3 and we should acknowledge that we don't yet have the technology we need for zero-carbon industry, air travel, maritime shipping, or other key sectors.

This is an agenda to “make more shit in America” both in the sense that we are talking about building lots of zero-carbon energy and also in the sense that cheap energy is a critical input to industry. Rooftop solar with battery backup isn’t going to power a factory, and you need to build big stuff in order to make stuff.

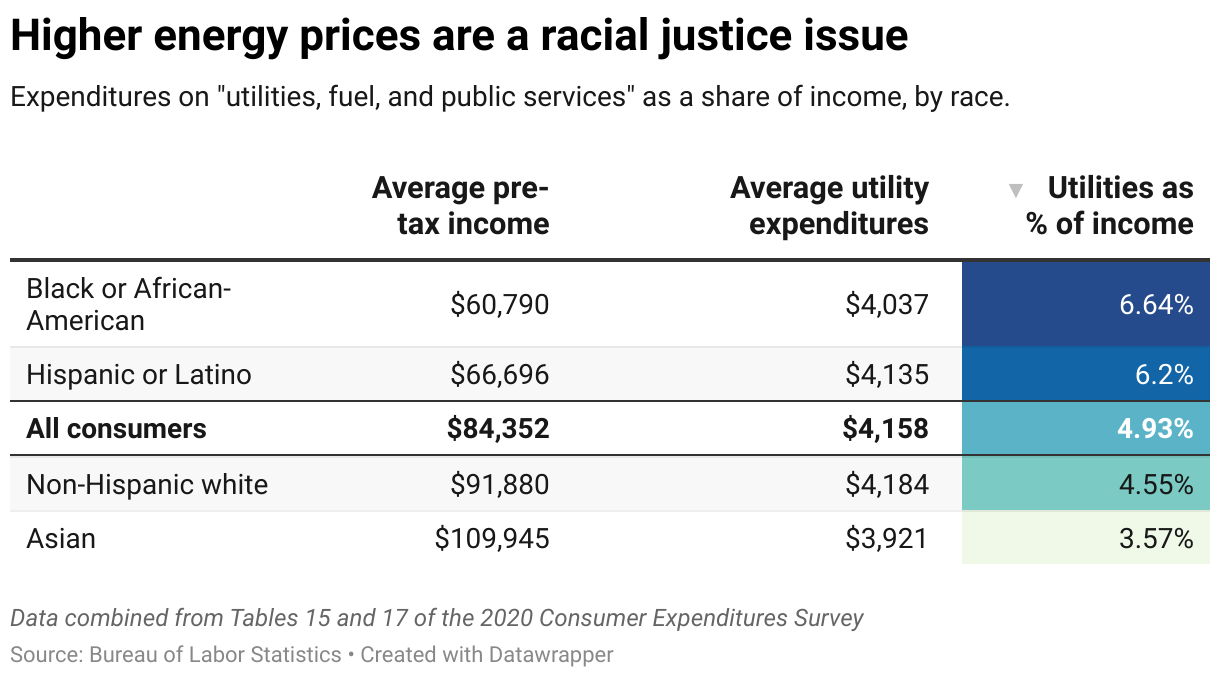

It’s also worth recalling that this has real distributive implications. I did this troll once about how cheap gasoline is a racial justice issue because Black and Hispanic families spend a higher share of their income on gas than white ones. The same is true, of course, of home utilities. Note that this is just trolling — the issue is that poorer people are disproportionately impacted by expensive energy costs — but that’s an important fact for progressives to understand.

If you conceptualize people’s “economic interests” purely in terms of the welfare state, then you’ll badly misunderstand the political alignments of the past quarter century.

The IRA itself was a critical step in reclaiming energy abundance as a progressive priority, but it needs followthrough in the next Congress. Fortunately, most of what needs to happen is doable through executive moves or on a bipartisan basis.

Full employment still matters

Some progressive senators have started complaining about the pace of interest rate increases, citing the harms of higher unemployment. I was touting full employment before it was cool, so I thoroughly agree. Still, when inflation has been this far above target for this long, something has to happen. The Fed could reasonably knock off the 0.75 percentage point increases and slow the pace to 0.5 or even 0.25 percentage points soon. But realistically, rates need to go up.

We can (and should) address that with deficit reduction, but that only underscores that welfare state expansion can’t be the driver of an agenda for shared prosperity.

What can be is the elimination of leaky buckets of upward redistribution. Higher interest rates are hammering the housing market, but there are still plenty of places where, thanks to overly strict zoning, the market price of homes vastly exceeds the cost of building them. Reform not only helps address housing costs, but it also maintains employment.

Similarly, even in recessions, we don’t see tons of unemployed doctors. Whatever the interest rate situation, there will be demand to hire foreign-trained medical professionals. And those doctors and dentists will get haircuts and shop in stores and dine in restaurants. Energy abundance directly addresses inflation and supports consumer spending on other topics.

All of which is to say, it is perfectly possible to maintain robust employment and economic growth during a time of rising interest rates. But it requires supply-side reforms, and those should especially be reforms that are progressive in their distributive impact.

This probably looks different if you consider the welfare of the chickens.

That’s what the textbooks call Pareto efficiency, and it’s rare.

Note that even if the electricity that charges your EV comes entirely from natural gas, that’s much lower emissions than what comes out of the tailpipe of an ICE car.

Could we step up the push to put tax-preparers out of work?

Legislation to have the IRS calculate your taxes and send you the bill. You verify it, or don't, and send them a check, or don't.

HR Block and Turbotax have to find new jobs.

"The origin of American zoning is largely in efforts to uphold racial segregation."

You see this claim a lot in progressive circles and it (a) doesn't really make sense and (b) is wholly unsupported by the linked studies and historiography. The paper linked in this work examines the use of zoning to enforce Racial Segregation in Southern Cities in the early 1900s. The idea that zoning would be used to uphold a de jure system of segregation that already existed is more or less unremarkable, horrific though it may be.

But "the origin of American zoning" is not found at all in the largely rural South. The paper you link to admits this in the second paragraph (!) saying "Benjamin Marsh championed zoning in the early 1900s in an effort to combat urban congestion and thereby improve the quality of working-class neighborhoods." Not only does this progressive, urban origin of zoning happen to be true, it also makes way more sense that an idea that originated in European urban renewal movements would first present itself in large, Northern American cities as opposed to smaller Southern ones.

This claim is akin to the ludicrous 1619 project claim that capitalism was invented in America (wrong) as a way to more efficiently facilitate the trade of enslaved people (also wrong). I don't understand why people feel the need to lie about this stuff, when it seems bad enough to me that the United States spend two centuries using otherwise anodyne or progressive advancements (urban renewal, ledger books) to facilitate the bondage and disenfranchisement of human beings. That is already bad! You don't need to pretend that Central Park is Jim Crow! IMHO it devalues the entire argument to make demonstrably false claims like this.