Deadweight loss, explained

The most important Econ 101 concept you've never heard of

This piece is written by Milan the Researcher, not the usual Matt-post.

The other day I sent my friend Gabe this Suraj Patel tweet that made me chuckle. He told me he didn’t get the joke because he didn’t know what “deadweight loss” meant.

And I’m guessing that a lot of people are like Gabe and don’t know what deadweight loss is — economics journalists rarely explicitly mention it. I’m sure that’s in part because readers don’t want articles full of weird jargon. At the same time, it really is a central concept to economics, and ignoring it can make policy decisions appear to be zero-sum tradeoffs when they’re really not.

I can’t let a good opportunity to explain basic economics concepts go to waste. So, here’s my attempt to share with you what my Econ 115 professor taught me.

Voluntary transactions generally make people better off

To understand deadweight loss, it’s important to first understand consumer surplus and producer surplus. And to understand those concepts, you need to understand a really basic supply and demand chart with the price of widgets on the vertical axis and the quantity of widgets sold on the horizontal axis. The line for demand slopes down, and the line for supply slopes up — as the price of a particular good increases, the quantity demanded goes down (the law of demand), whereas the quantity supplied increases with price (the law of supply).

In a perfectly competitive market — homogenous goods, tons of buyers and sellers, and perfect information — price and quantity settle into equilibrium at the intersection of the supply and demand lines.

But we know that some consumers who bought at the equilibrium price would still have bought if the price had been higher. And some producers who sold at the equilibrium price would have sold even if the price had been lower. That difference between the actual transaction and the hypothetical transactions you would have been willing to do is the surplus.

When Gabe came to visit me in New Haven, we went to Popeyes around midnight. He bought a spicy chicken sandwich for $4, but he would’ve been willing to pay up to $6 for some late-night grub (dining halls close at 7), so he gained $2 of value from the transaction. This is called consumer surplus.

We can measure the value derived by sellers the same way, finding the difference between the actual price the local Popeyes sells a sandwich for and the minimum price they would have accepted — that’s producer surplus. When you plot the supply and demand lines and layer on producer and consumer surplus, you get the chart above.

The consumer and producer surpluses represent the value that both Gabe and Popeyes gain from the transaction in which he gives them $4 and they give him a chicken sandwich. The total surplus is just the sum of the two. A normal business transaction involves redistribution — someone gets money, someone else gets a sandwich — but it’s not just redistribution. Voluntary transactions take place because both parties derive surplus from the exchange of money for sandwiches.

The cost of blocked transactions

The caveat here is that we’ve been assuming that price and quantity remain at the market equilibrium. But what happens when they don’t? What if Joe Biden tries to halt inflation by mandating a $3 cap on the price of chicken sandwiches?

At first glance, this seems like a straightforward transfer from producers to consumers. The local Popeyes would take a hit to their profits, reducing their producer surplus because the price cap narrows the gap between the minimum price they’d take and the actual price. By the same mechanism, Gabe’s consumer surplus would increase, since the gap between the maximum price he’d pay and what he actually pays increased.

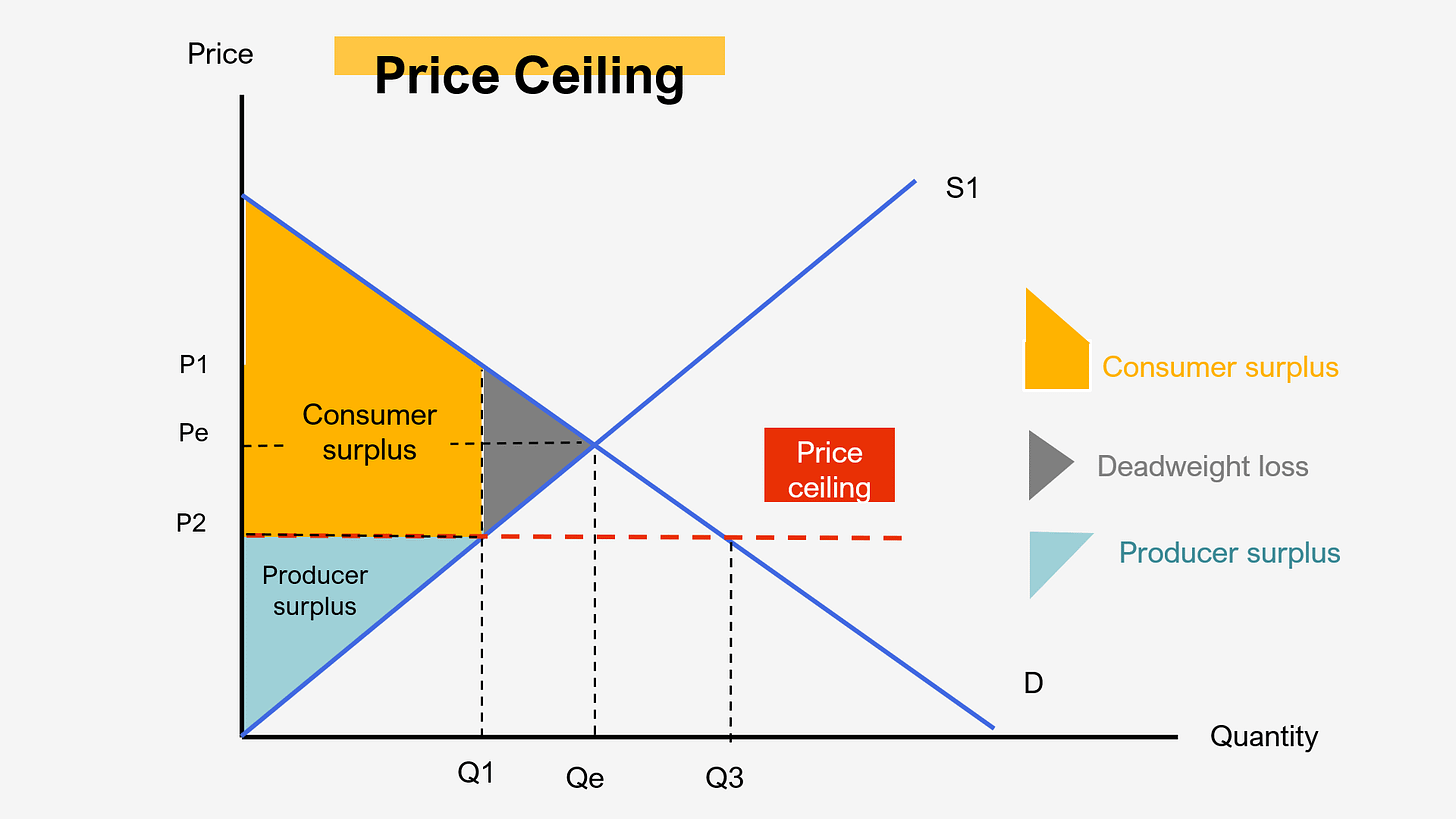

If you look at this chart, that’s what you see. Compared to the market equilibrium price Pe, the consumer surplus is larger after the price ceiling is applied and the producer surplus is smaller.

But if the price of sandwiches is capped at $3, Popeyes’ is going to sell fewer sandwiches because the marginal sandwich becomes unprofitable. If it costs them $2 in ingredients and labor to make the sandwich, then maybe it makes sense to keep the store open at midnight on a Saturday when each sandwich nets a $2 profit. But if a sandwich only nets $1, then keeping the store open for those late-night customers might not be worth it anymore. And if Popeyes closes at 10 p.m., then I lose out on the opportunity to get a sandwich when I’m hungry at midnight.

And that’s deadweight loss: the lost value of the transactions that don’t occur as a result of the price cap. More formally, it’s the sum of lost producer and consumer surplus as you move from the equilibrium quantity (Qe on the chart) to the quantity produced under the price cap (Q1).

Going back to our Popeyes example, it turns out that the $3 price cap isn’t a strict transfer from producers to consumers. That is happening, but both parties are taking a hit to their respective surplus. It seems like the surplus that consumers gain is larger than the surplus they lose as deadweight loss, but note that the total surplus has actually decreased. It’s not a zero-sum transfer — it’s negative-sum! When the late economist Arthur Okun observed that redistributive policies can be a “leaky bucket,” this is the kind of situation he had in mind.

DWL IRL

Price controls on chicken sandwiches aren’t a policy that’s actually on the table. But one area where deadweight loss does come into play in the real world is tax policy.

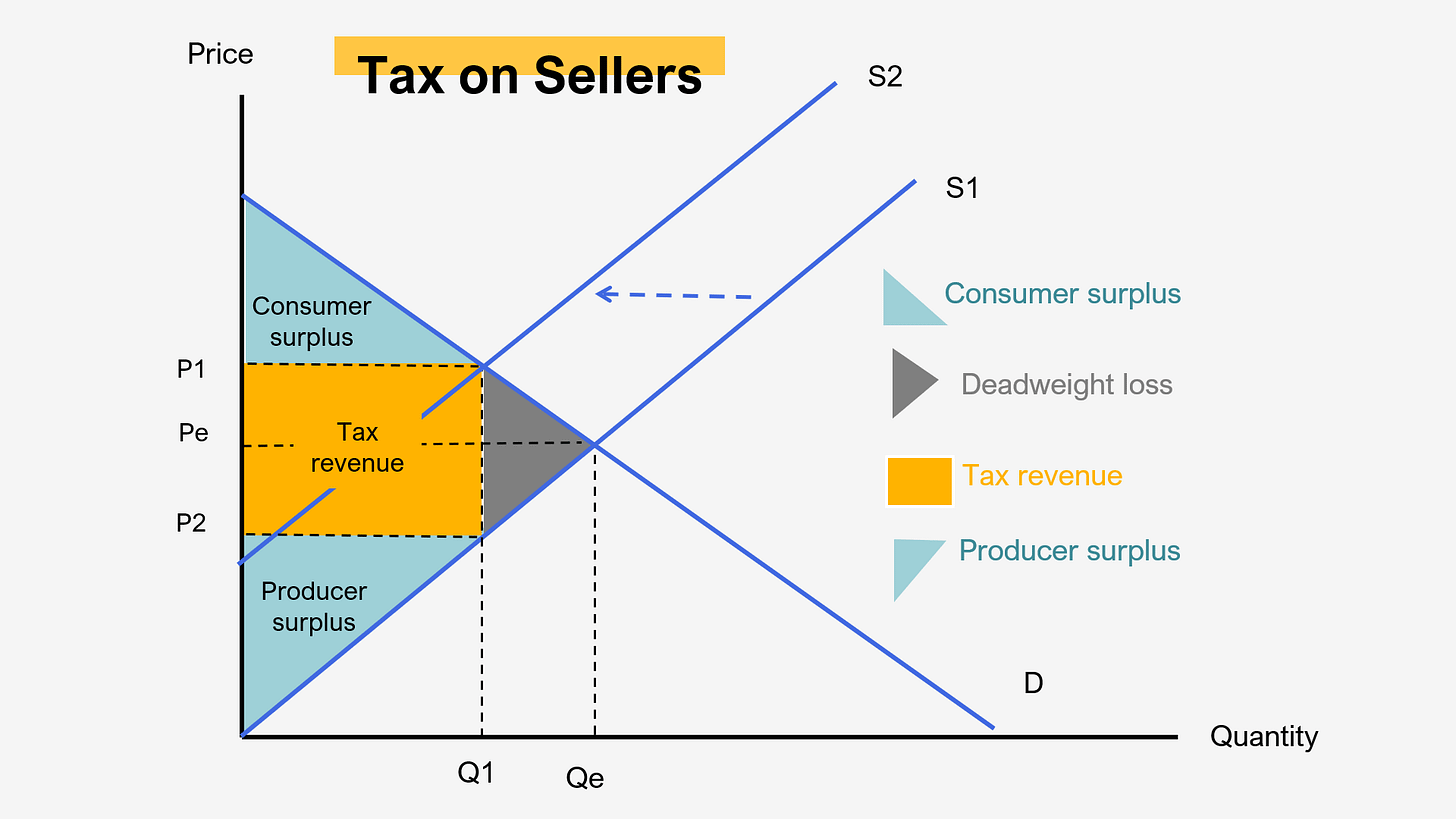

Think about the federal gas tax. It’s currently a little over 18 cents per gallon. You and I don’t send Uncle Sam a check every time we buy gas, the gas station does. But the gas station passes that cost onto consumers. That’s what economists mean when they distinguish between the imposition of a tax and its incidence — it’s the difference between who the tax is formally applied to and who actually pays. Governments usually opt for taxes imposed on sellers, because it would be a huge headache to, for example, have drivers write the government a check every time they buy gas.

Because of taxes, the gas supply is lower than it would be in a completely free market, which means some people aren’t buying gas who would be if there was no tax — that’s the deadweight loss. Buyers and sellers share the incidence of the tax,1 and a chunk of both consumer and producer surplus gets turned into tax revenue.

The fact that total surplus shrinks may lead you to believe that all taxes (except on land — more on that later) are bad, but there are two important and related caveats.

First, it matters what you’re taxing. Some transactions have negative effects called “externalities” that affect people other than the buyer and seller and reduce total surplus. Air pollution is an externality of burning fossil fuels, so if the gas tax reduces gasoline consumption, that offsets the deadweight loss incurred by some people not buying gas. Taxes on goods with negative externalities are called Pigouvian taxes, and they can have zero or even negative deadweight loss, depending on how high they’re set. In his textbook, former Bush CEA chair Greg Mankiw advocates for a gas tax of over $2 to fully account for pollution externalities, traffic congestion, and damage to roads.

Second, it matters what you’re spending the money on. If you’re in a state where sports betting is legal, taxing gambling might have some benefit in decreasing problematic behavior on the margin but still creates deadweight loss. But if you spend the money on providing free school lunches to all kids, the benefits to hungry children could outweigh the lost utility to hobbyist gamblers.

The application to housing

A lot of coverage of housing policy leaves out the concept of deadweight loss.

Instead, both critics of the status quo and its defenders often use an implicit framing in which NIMBY policies are a straight transfer from renters who bear the cost of higher rents to homeowners who enjoy a higher net worth. In other words, a transfer from consumers of housing to producers of it.

What this misses is the lost value of the housing that doesn’t exist because of bad policy. When you make it harder to build housing, it’s harder for people to find a place to live where they want to for an affordable price. And as Matt wrote in “Homeowners should be YIMBYs,” land use restrictions decrease the value of a homeowner’s property by reducing the number of things they can do with that property.

Of course, it’s much easier to recognize the transfer of consumer surplus to producers. Both student renters and landlords in Santa Clara are very much aware that rents are through the roof and supply is woefully inadequate. It’s much harder to “feel” the deadweight loss that’s happening here precisely because deadweight loss is the value of transactions that don’t happen. But it’s a really big deal — according to Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, restrictive zoning policies reduced American economic growth by 36 percent2 from 1964 to 2009.

Better zoning policies would make it easier to find a place to rent. It would also be easier to find someone to rent your spare unit to if the asking price were closer to the market equilibrium — that’s a win-win. Leaving deadweight loss out of the analysis obscures that point and makes the whole situation seem like a zero-sum conflict where any win for renters comes at the expense of homeowners or vice-versa. But the zoning transfer to homeowners is an extremely leaky bucket. We can’t guarantee that literally every person would be better off if we reduced deadweight loss, but the average benefits would exceed the costs.

Equality and efficiency

The leaky bucket metaphor comes from an essay titled “Equality and Efficiency: The Big Tradeoff,” the premise of which is that because redistributive policies tend to entail deadweight loss, there is a tradeoff (a big one!) between equality and efficiency. But limiting the number of units that can be built on a given parcel of land is a leaky policy that redistributes upward toward homeowners who are richer on average than renters. It’s inefficient, but it’s also inegalitarian.

And many policies have this structure. For example, say you wanted to raise tax revenue while minimizing deadweight loss. What you’d want to do is tax goods with very low elasticity of demand or supply. What does that mean? Consider the Halloween pumpkin market.

Once a farmer plants their fields, they’re pretty much locked into a given level of pumpkin production — the supply is inelastic. So if the government imposes a jack-o’-lantern tax, the farmer can’t really cut supply, but consumers can easily buy fewer pumpkins, so the farmer ends up eating most of the tax. By the same logic, a tax on a good with very inelastic demand will result in consumers bearing most of the incidence.

The problem is that the goods with the lowest elasticity tend to be necessities, like medicine or food. If you taxed insulin at $20/vial, you would probably collect a lot of tax revenue from diabetics with no choice but to pay, but it would obviously be incredibly cruel. This is the tradeoff in action. The most economically efficient policies — the ones that minimize market distortion — are also generally the least egalitarian.

A land value tax would avoid this problem since the fact that the supply of land is fixed means that you can avoid deadweight loss without balancing the budget on the backs of diabetics or the hungry.

I’ll spare you the math, but the incidence of a tax is the same regardless of whether it’s imposed on the buyer or the seller.

Not a typo!

A great example of "deadweight loss" are restrictions on surge pricing for ride share companies. No surge pricing to get drivers on the road=no ride home from the ballgame for me.

Great explanation of deadweight loss. I’d add the concepts of fixed costs vs. variable costs as a contributing factor to why suppliers decrease quantity with a price cap.

* Fixed costs: Costs a supplier pays regardless of quantity sold

* Variable costs: Cost per-a-unit of production

In the Popeyes example

* Fixed: Lease, maintenance, wages of a minimal crew

* Variable: Ingredients, wages of additional workers at busy times

With the price ceiling, Popeyes could find that sales after 10 PM doesn’t provide enough revenue to offset the costs of the minimum crew needed to operate a store. They could also find that some locations should be closed since they don’t bring in enough revenue to cover their fixed costs regardless of hours of operation.