Affordability means hard choices

Tackling cost pressures is going to mean taking on some sacred cows.

For anyone interested in both a career in journalism and the kinds of issues we cover at Slow Boring, our friends at The Argument are hiring for several full-time positions, including an editor and a video podcast producer. They’re also looking for their first cohort of fellows — early-career writers interested in focusing on abundance and economic policy; gender, families, and culture; technology and society; and/or polling and political analysis.

Donald Trump, who is not much of a policy wonk but does enjoy living life unencumbered by principles, recently announced that he is reversing course on tariffs for beef, coffee, and certain other grocery categories to address voter concerns about the cost of living.

Trump owes his biggest strengths as a politician to the cult-like structure of the MAGA movement, which allowed him to impose these counterproductive tariffs for months without conservative influencers complaining. Impressively, he now also appears to be able to remove them without meaningful backlash from within the movement.

Democrats struggle more with this dynamic. The Biden administration kicked around various proposals to make a big show of addressing the cost of living, but many of them bumped up against the interests of labor unions, environmental groups, and other progressive policy-demanders. I think Biden should have pulled the trigger on more of them anyway, but intra-coalition backlash and blowback is genuinely a bigger concern on the Democratic side.

And this, I suppose, is my biggest question about the new party-wide consensus in favor of a message focused on affordability. The political opportunity is clearly there; voters care about it and they think Trump is failing. And Trump has created an opportunity for Democrats by blundering away from certain Republican positions like free trade, by embracing NIMBYism, and by imposing an immigration policy that goes way beyond border security to do real harm to the broad American economy (and of course to the families directly impacted).

But prioritizing the cost of living means deprioritizing other things, which in turn requires confronting tradeoffs and making clear choices.

A recent example — and one that relates to my personal interests — is that the New York state legislature passed a bill back in June requiring all New York City subway lines to operate with two-person crews (one driver and one conductor) indefinitely. This is how the subway already works, but the requirement is unusual globally and obviously raises the cost of subway operations.

What’s more, while self-driving cars present a difficult (though increasingly solved) problem, self-driving trains are much easier to implement since they run on tracks. Retrofitting an existing train line is expensive, but New York is starting work on a brand new train line — the Interborough Express — and it’s totally crazy to build a brand new train line in 2025 that’s not designed to be automated.

The Transit Costs Project at NYU released a report on this topic, and noted that not only do fewer than 7 percent of train lines globally operate with two-person crews, the Japanese cities that do this are all currently investing in technology to allow one-person or zero-person operation.

On the theory that Democrats are now very interested in affordability, it should be a total no-brainer for Kathy Hochul to veto the bill.

By the same token, given Zohran Mamdani’s interest in reducing bus fares, he ought to be very interested in the question of why New York City buses have higher costs per mile and per hour than the public buses in Boston, D.C., or San Francisco.1

In both cases, though, to focus on affordable transit would mean crossing the demands of narrow union interests. The New York Times did a story on this where they got the president of the Transport Workers Union to say “it doesn’t really matter to us what the data shows” in terms of whether two-person crews have the benefits he’s claiming they have.

That’s fair enough, I guess. But if you’re a politician who wants to prioritize the cost of living, you do have to care about facts and data.

The affordability skinsuit

I think this shift has been particularly obvious in the energy space, where progressive groups have made a strong pivot to affordability. Their new message has two good things going for it:

Trump’s effort to cripple renewables deployment on public lands is genuinely bad for costs.

Building renewables is, in many cases, legitimately the lowest-cost option due to the falling cost of solar panels and batteries.

But none of the environmental groups have actually pivoted to promoting affordability by centering their advocacy on removing barriers to renewables deployment.

Instead, they’ve all donned a kind of affordability skinsuit while continuing to advance a policy agenda focused almost entirely on blocking fossil fuel infrastructure.

It’s not just that they care about renewables more than they care about affordability; they care about blocking natural gas pipelines more than they care about promoting renewables. There are ongoing bipartisan talks on Capitol Hill where members of Congress are trying to reach a permitting reform deal that would be win-win for pipelines and solar. We saw two previous iterations of these talks collapse in part because the green groups have no interest in such a deal, and I see zero sign that they’ve become more supportive now.

When Josh Shapiro proposed a state-level version of this kind of idea — he called it the Lightning Plan — environmental groups opposed it. And Politico ran an article just last week about how environmentalists are outraged at Hochul because she’s prioritizing affordability in her thinking about pipelines. Apparently they only wanted her to pretend to prioritize affordability.

My problem with that article, though, is that I think the authors are too eager to accept the green groups’ argument that there’s a sharp tradeoff here. It seems to me that in the context of the Northeast, cheaper gas reduces emissions both by encouraging a switch away from dirtier fuel oil for heat and by supporting electrification via cheaper electricity.

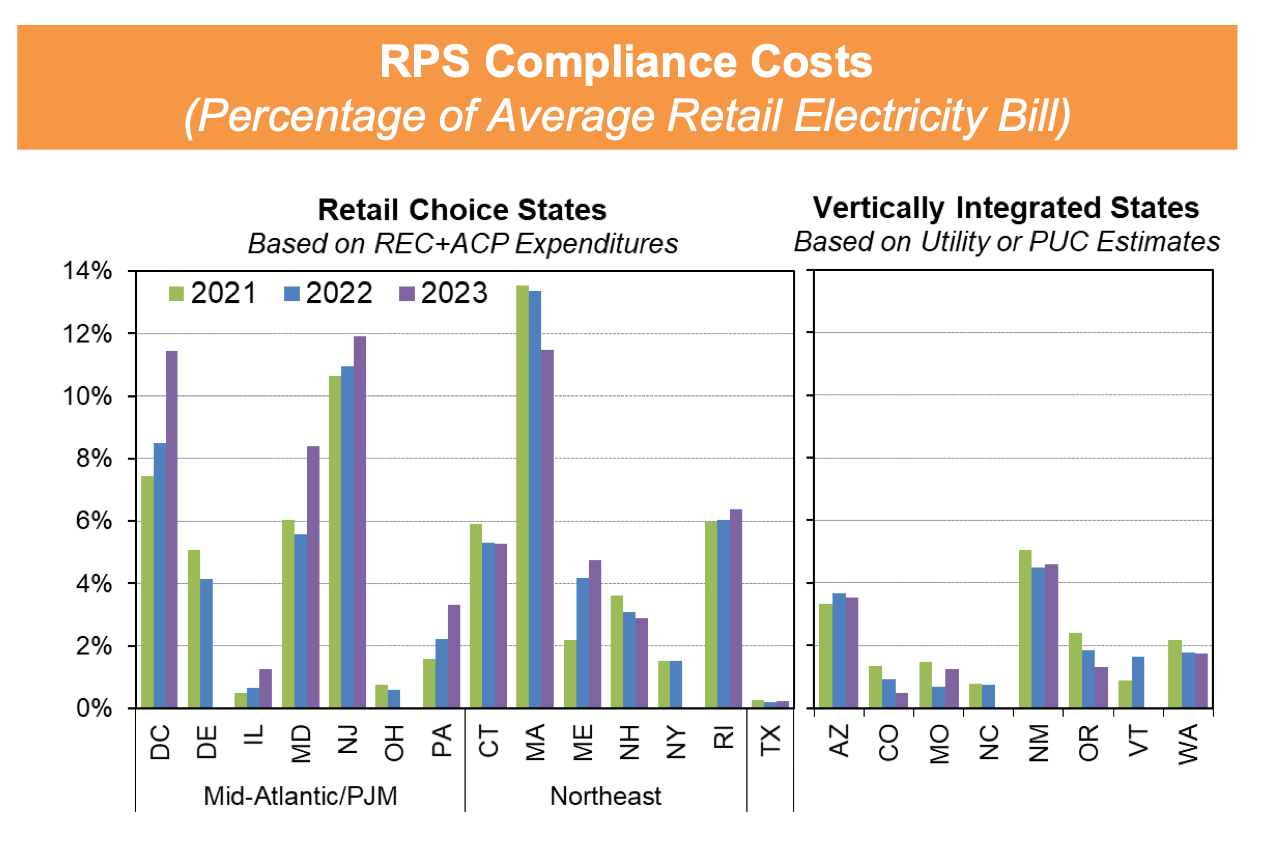

Another version of this dilemma is about to occur in New Jersey, where Governor-elect Mikie Sherrill won in part on a promise to freeze electricity prices. It is not at all clear how she plans to accomplish this. One idea would be to note that, according to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, New Jersey has some of the highest compliance costs for its renewables portfolio standard (RPS). The lab estimates that New Jersey’s compliance costs from the RPS add a bit over 10 percent to the average electricity bill.

The basic issue is that there’s something of a mismatch between the states that have the greatest legislative enthusiasm for climate initiatives and the states that have the most actual capacity to do large-scale renewables deployment.

The northeastern United States in particular is densely populated, not especially windy, and extremely lacking in sunshine. Texas features large swathes of privately owned arid land that has little economic value and can be gainfully transformed into large-scale solar projects, but New Jersey does not. Sherrill sensibly says that the long-term solution for America’s most densely populated state is nuclear, but even a real nuclear optimist knows that’s not going to be achieved next year.

Bharat Ramamurti, a very smart economic-policy guy who worked in the Biden administration and for Elizabeth Warren, says that “targeted price controls, alongside aggressive measures to boost the supply of things like housing and clean energy, may be the least worst option out of the cost-of-living crisis we’re facing.” But why does the supply side reform have to be clean energy? Why, in New Jersey’s case, can’t it be waiving or relaxing the RPS? If the answer is that constraining natural gas use is more important than addressing the cost of living, then that’s fine. But that’s donning the skinsuit rather than prioritizing affordability.

Policy is full of annoying tradeoffs

I read a paper last fall about the Buy American Act, which requires the federal government to use American firms for a range of procurement purposes. This sounds like a nice idea, and you can see why elected officials might support it. But the researchers’ conclusion was that it creates jobs at a fiscal cost of $111,500 to $137,700 per job.

That’s not a very good deal.

It also understates the full economic cost of the program — not just the fact that the federal government is overspending on various things, but that the workers doing those jobs are no longer available to do anything else.

This is also a glaring problem with MAGAnomics. Over the weekend, a big raid in Florida targeted immigrants working as tomato-pickers. Some of the people detained were apparently legal residents, and I have serious concerns about ICE hassling American citizens on the basis of racial profiling or supposition.

But even leaving that aside, plenty of farmworkers are here illegally, and who is supposed to do that work if we deport them or scare them off? Some people say they’re here doing the jobs “Americans won’t do.” Others might respond that if you raised wages, some American would do the job. But then the job that person was previously doing will be empty. There just isn’t some enormous pool of unemployed Americans available to go pick tomatoes or work in a sock factory or whatever other job opportunities the Trump administration thinks they’re creating with tariffs and mass deportation.

Their version of skinsuiting is to claim that their anti-immigration crackdown is housing affordability policy. But if you’re trying to make housing cheaper by reducing demand, you’d actually want to focus on the highest-paid, most economically valuable immigrants. Elon Musk does a lot more to raise real estate prices than any seasonal tomato-picker. Besides which, the administration is also raiding construction sites. Trump’s first-term immigration policies appear to have raised housing costs by driving up the price of construction.

And yet, even Democrats who are eager to oppose the administration on immigration are unlikely to argue that what he’s doing is bad because it’s driving up the cost of farm labor. That’s not an argument that sounds good.

The general problem is that your costs are my income and vice versa, so many cost-reducing ideas involve some unpleasant tradeoffs.

Politicians are interested in policies that sound like they can bring costs down purely by sticking it to unsympathetic actors, but this is rarely the actual situation. You’re more likely to get the reverse, like earlier this fall when the City Council in New York voted in favor of a rule that only a master plumber can hook up a gas stove. This is good for the extremely small number of master plumbers in N.Y.C. — there are only 1,000 of them in the whole city — and that was apparently good enough to secure a 47-1 win when it came up for a vote.

It would be convenient for Democrats if it were easy to connect affordability to billionaire “oligarchs,” but it’s pretty clearly not the case that the high-margin advertising businesses run by Facebook and Google are responsible for the high cost of living. You can get an iPhone 16 today for the same nominal price as an iPhone 11 in 2019.

Especially when you’re talking about Democrats who are governing in blue states, the vast majority of opportunities to get serious about the cost of living are going to involve tackling relatively friendly interest groups, and that’s inevitably going to get ugly.

To an extent, I think Democrats should recognize that the “affordability” crisis is mostly people being mad that Trump can’t deliver on his promise to make nominal prices lower and it’s a political free kick for them. But at a minimum, they should avoid passing or signing laws that will make things worse.

Note that I picked three cities that are in metro areas with higher average wages than New York!

Gonna do a little self promotion here and drop my piece in Vital City about how Mamdani might tackle some of these issue: https://www.vitalcitynyc.org/articles/zohran-mamdani-michelle-wu-and-brandon-johnson

Very good post, and I’m glad it’s strategically unpaywalled. But this is my first encounter with the “skinsuit” metaphor and it kind of creeps me out.

ETA: this is a very widespread problem. On the transpo and infrastructure projects I work on, there are all kinds of procurement rules as well as rules governing the hiring of consultants like us (eg, a percentage of women- and minority-owned subconsultants on the team). Most people know this—I knew it before I worked in this domain—but to see it in action is truly remarkable, and not in a good way. The problem is so big and so enmeshed in the system that it seems impossible to unwind. Earlier this year, I nurtured a tiny ember of hope that the wanton destruction would open up an opportunity to build a better system, but per this post that doesn’t seem likely.