Climate policy should reduce greenhouse gas emissions

A modest proposal

That headline seems stupid, right? Like reasonable people can disagree about all kinds of things. But if you’re trying to make climate policy, obviously you’re going to propose ideas that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, right? Bueller? Anyone?

In other news, on October 15, Hilary Howard and Grace Ashford wrote a story for the New York Times headlined “N.Y. Democrats Urge Hochul to Reject Pipeline Over Climate Concerns.”

The article is about the Northeast Supply Enhancement project, a proposed pipeline from New Jersey into the Rockaways that would increase the amount of natural gas that can be shipped from the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania to the northeastern United States.

Specifically, it’s about a letter signed by New York City House Democrats — including Hakeem Jeffries, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Dan Goldman, Nydia Velázquez, and Ritchie Torres — opposing the pipeline.

Those representatives, in short, span the factional divides that captivate the internet — they include pro-Israel Democrats and critics of the U.S.-Israel alliance, those who identify with the abundance movement and those who identify as populists. Yet this disparate group of Democrats is united in opposing the project on climate grounds.

A curious and alert New York Times reader might want to know what exactly these concerns are. How much will the pipeline increase emissions? Are we talking about an increase in localized carbon emissions in New York State or an increase in global emissions? We know that climate change is not considered a priority by most voters and that all factions of Democrats are (supposedly) focused on affordability and the cost of living.

But still, perhaps you care a lot about climate change and think it’s worth asking voters to pay a price for reduced emissions. You might want to know what price and how much emissions reduction we’re talking about.

The article doesn’t say because the letter doesn’t say.

Which is a remarkable fact that, were it my article, I would have made note of. Those critics know that they’re against the pipeline. They know that the reason they’re against the pipeline is climate concerns. But again, what are the concerns?

In defense of the letter writers, the reason they don’t have even back-of-the-envelope modeling of how much the pipeline will increase emissions is that this is actually an incredibly challenging modeling exercise. On the other hand, suppose you’re the governor of New York State and a proposal for a project lands on your desk. The project will create jobs and stimulate other economic activity. It will reduce energy costs for your constituents.

But people are asking you to say no to it due to climate concerns. And those people can’t tell you — not even a vague estimate — what the climate impact will be. I would not act on these objections. And in particular, I would not act on objections of that nature when the emissions impact of the project could very likely be negative.

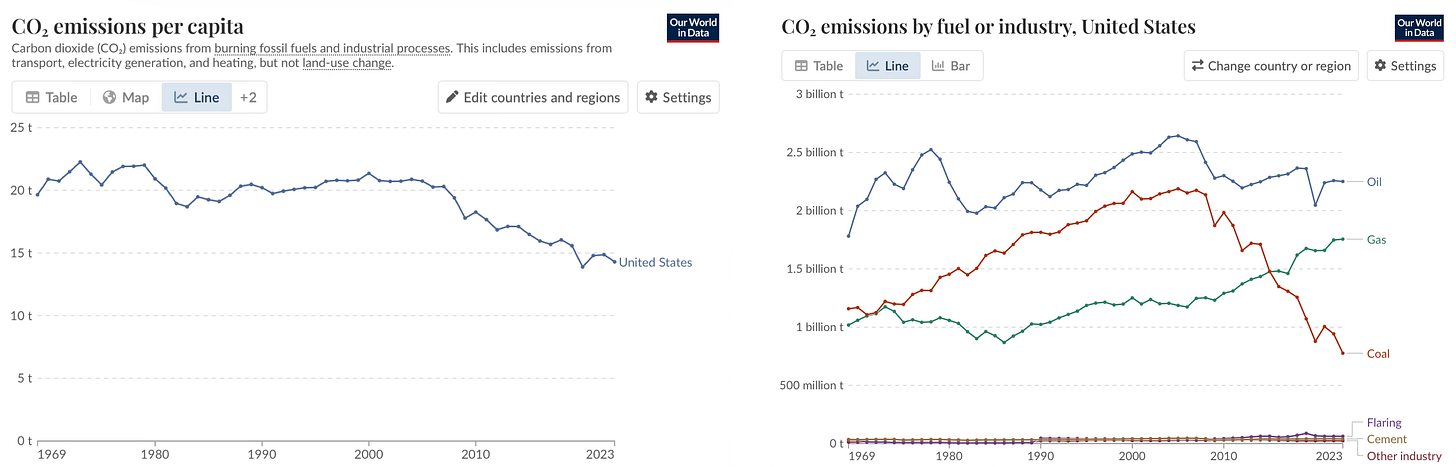

Note, for example, that American emissions have been going down since the domestic natural gas boom began, around 2007, because replacing coal with gas reduces emissions.

The northeastern United States no longer has coal plants, so delivering additional natural gas there will not reduce emissions through that particular mechanism. But both the global and regional energy situations are complex, and I think there’s still a reasonable case that this pipeline will reduce emissions.

The climate case for a pipeline

The letter writers claim that a pipeline is economically pointless because “gas consumption in New York is projected to remain flat or decline due to increased renewable generation and improved efficiency.”

The reality is that, due to pipeline constraints, the northeastern United States currently imports a good amount of liquified natural gas. The point of liquifying gas is that you can put it on boats. This boat-borne gas trades on a global market at a higher price than domestic natural gas, the price of which is depressed by limited export infrastructure and a shortage of pipelines connecting to northeastern markets. Building more pipelines would provide the Northeast with access to cheaper piped gas. This will decrease northeastern gas prices relative to a “no pipeline” counterfactual. It will also somewhat raise national gas prices, and (by a smaller amount) reduce global gas prices.

The most important potential climate impact of the pipeline is that gas-burning furnaces emit 40 percent less greenhouse gases than oil-burning furnaces, so making it cheaper to switch has large environmental benefits. More abundant gas could also reduce the region’s reliance on dirtier oil- and coal-burning peaker plants during periods of very high electricity demand.

Speaking of electricity, everyone seems to agree that we should be encouraging the use of electric cars and electric heat pumps rather than fossil-fuel-burning options for transportation and home heat. How attractive those options are, from a consumer standpoint, is in part a function of electricity prices. The lowest emissions option, of course, is for heat pumps and electric cars to be powered by 100 percent zero-emissions electricity. But a large gas-fired power plant is more efficient than a home gas furnace, and gas is clean compared to fuel oil or gasoline. So a program of burning natural gas to generate electricity to displace internal combustion engines and home furnaces is a program to bring emissions down.

I will be the first to admit that this is an imperfect and imprecise model. But I believe that more pipelines to bring Marcellus Shale gas to the northeastern United States will make emissions lower, not higher, relative to a counterfactual in which we refuse to build pipelines.

Paying an economic price in order to reduce emissions may be dicey politics, but it’s not a crazy idea. But paying a price in order to make emissions higher is absurd. Pipeline opponents have simply not bothered to try to explain why this is wrong or what climate concerns exactly they have.

Taking northeastern energy seriously

I think most people probably just assume that if a bunch of environmentalists are saying a pipeline is bad for climate, the pipeline is bad for climate.

But consider Indian Point.

When Andrew Cuomo, R.F.K. Jr., and the Natural Resources Defense Council teamed up to close this New York nuclear plant, many warned that eliminating a major source of zero-emissions electricity would make emissions higher.

That is in fact exactly what happened, which seems really obvious. The counterargument at the time was that this would be fine because renewable power was growing rapidly. Well, they were wrong, and it didn’t grow quickly enough. But in some ways that’s just a cheap rhetorical point. Even if renewables had grown fast enough to replace the Indian Point energy, it’s still the case that turning the nuclear plant off would lead to higher emissions relative to a counterfactual in which it wasn’t turned off.

New York State is simply not in danger of having an overabundance of zero-emissions electricity. New York is burning lots of fossil fuels to generate electricity and to heat homes and power vehicles. The state’s electricity prices are 50 percent higher than the national average. New Yorkers can use all the supply they can get.

I bring up the Indian Point saga to illustrate that, however incredulous it might sound that Joe Newsletter Writer is correct about the emissions impact of the pipeline and the professional environmental advocates are wrong, these people have a terrible forecasting track record that is grounded in a fundamentally bad analytic framework.

A few years ago, they didn’t want nuclear because we could build renewables instead. Now, they don’t want gas because we can build renewables instead. But two questions:

Why “instead”? What’s the tradeoff?

What’s the 100 percent renewable vision for the Northeast anyway?

Onshore wind generates a lot of electricity in places where it’s quite windy, which is why a lot of Great Plains states combine high renewables share with cheap electricity. But it’s not that windy in the Northeast. It’s also the least sunny part of the country, with the exception of Washington State, which happens to have a quarter of America’s hydroelectric power.

This is not to say that there is no renewable energy in the Northeast or no prospect for building more. But the northeastern United States is not a place where building renewable energy is particularly economical.

A state willing to pay a price to meet its climate goals can, of course, choose to subsidize a renewables buildout, but there’s a real fiscal tradeoff with things like schools and Medicaid. You could say “instead of paying teachers high salaries, we should build renewables instead.” Or “instead of giving generous health benefits to poor people, we should build renewables instead.” But a gas pipeline does not reduce the state’s capacity to subsidize renewable energy. There is no tradeoff. If anything, by bringing the price of energy down, it makes it easier to subsidize renewables.

There’s also the question of what you’re actually building.

In my experience, residents of the Northeast are more invested in the climate issue than residents of Texas or Iowa, and also more skeptical of cutting down huge swathes of forest to build utility-scale wind and solar plants. People in states with agriculture-intensive economies are more comfortable with this sort of project. That’s why northeastern states gravitated toward offshore wind projects, which were suffering from exploding construction costs even before the Trump administration started canceling them.

There’s no realistic counterfactual analysis in which blocking the gas pipeline leads to a surge of renewables construction. If you want to build more renewables, by all means, identify the policy obstacles and do that. But the question to ask about the pipeline is whether building it will make emissions go up relative to not building it — and there’s just not a compelling reason to think the answer is yes.

The perils of backwards reasoning

So what’s going on here?

Back in the stone age of 2009, the prevailing thought on addressing climate change was that there would be a binding international treaty aimed at limiting emissions such that total climate change would be limited to two degrees Celsius. That treaty would, among other things, commit various countries to legally binding emissions targets. In the United States (and presumably elsewhere), that would involve a statutory cap on greenhouse gas emissions, with emitters needing to obtain emissions permits either through direct government allocation or by purchasing them on a market. That was “cap and trade.”

The legally binding cap would, of course, constrain emissions in any given year.

But it would also inform investment decisions. With the cap falling over time, everyone would know that, in the future, aggregate fossil fuel use would have to be lower rather than higher. So you wouldn’t build a new pipeline in 2020 that would take decades to pay off if you knew the infrastructure had to be retired in 2030. The country would plow ahead into a future where the energy mix was cleaner than in the no-cap scenario, but also where energy is just generally scarcer and somewhat more expensive. Daily life in the United States would look more like it does in Europe, where energy is more expensive and there is a lot more emphasis on efficiency.

Whatever one makes of this vision, the fact is it didn’t happen. There was no globally binding treating, there was no cap and trade bill, and the world is not going to limit warming to two degrees Celsius.

Unfortunately, a lot of people who genuinely care about this issue are stuck reasoning backwards from these phantom targets. It is probably true that building new natural gas pipelines is not consistent with the United States becoming a net zero economy by 2050. In that scenario, the Northeast would electrify transportation and home heat regardless of electricity prices, and electricity prices would simply go as high as they need to go in order to make offshore wind and other renewables pencil out.

But this is a thought experiment or science fiction.

Democrats need to forget about the hypothetical scenario in which pipeline approvals are being made in the context of a national cap and trade system that operates in the context of a legally binding international treaty.

Instead, they need to think about the actual question at hand: Will emissions be higher or lower if we build the pipeline? If they are very, very sure that emissions will be higher, that’s the beginning of an argument against the pipeline.

You do have to actually ask the question, though.

And even though it sounds hard to believe that anyone would fail to ask that question, I truly believe that they are failing to. That’s why Indian Point was closed, that’s why there’s no environmental groups engaging in the fight over New York’s housing charter amendments, and it’s why calls to block pipelines come with no analysis on the merits of the actual impact.

Elsewhere on Slow Boring: how Los Angeles is rethinking its public spaces ahead of the 2028 Olympics.

It's worth highlighting that gas supplies in the Northeast are so low relative to demand that gas-fired power plants cannot be used in the coldest part of winter. So on cold days, the supply of electricity shifts towards oil, which is much dirtier. (See the ISO graphs below).

This factor, combined with retiring Indian Point and Vermont Yankee, have pushed electricity prices up dramatically - and this, in turn, makes it unattractive to switch from oil heat to heat pumps. (MA this winter started heavily subsidizing electric heat in an attempt to make it more economically attractive.)

https://www.iso-ne.com/about/where-we-are-going/power-plant-retirements

For all the justified criticicim made of "environmental" groups for failing to promote the lowest cost policies to reduce net CO2 emissions, the MSM, the NYT being the most MS of all, fail to raise the issue either. When researching this post [ https://thomaslhutcheson.substack.com/p/climate-decision-making-1] I noticed that the coverage never mentioned how much mor or less CO2 would go into the atomosphere as a result of a decision one way or the othere and at what cost cost or benefit. It DID mention the politics of the decision, but not the costs and benefits. That's just bad journalism.