A Senate majority could be within Democrats’ reach

That’s the real lesson of the Tennessee special — just don’t blow it

I wasn’t paying much attention to last week’s special election in Tennessee until the votes came in and a little factional squabbling started about whether that race would have been winnable had Democrats not nominated such a progressive candidate.

It’s a very red seat, and I think clearly Democrats should have tried to nominate someone better-suited to the district. But also, it’s a very red seat, and basically any candidate Democrats nominated would have lost.

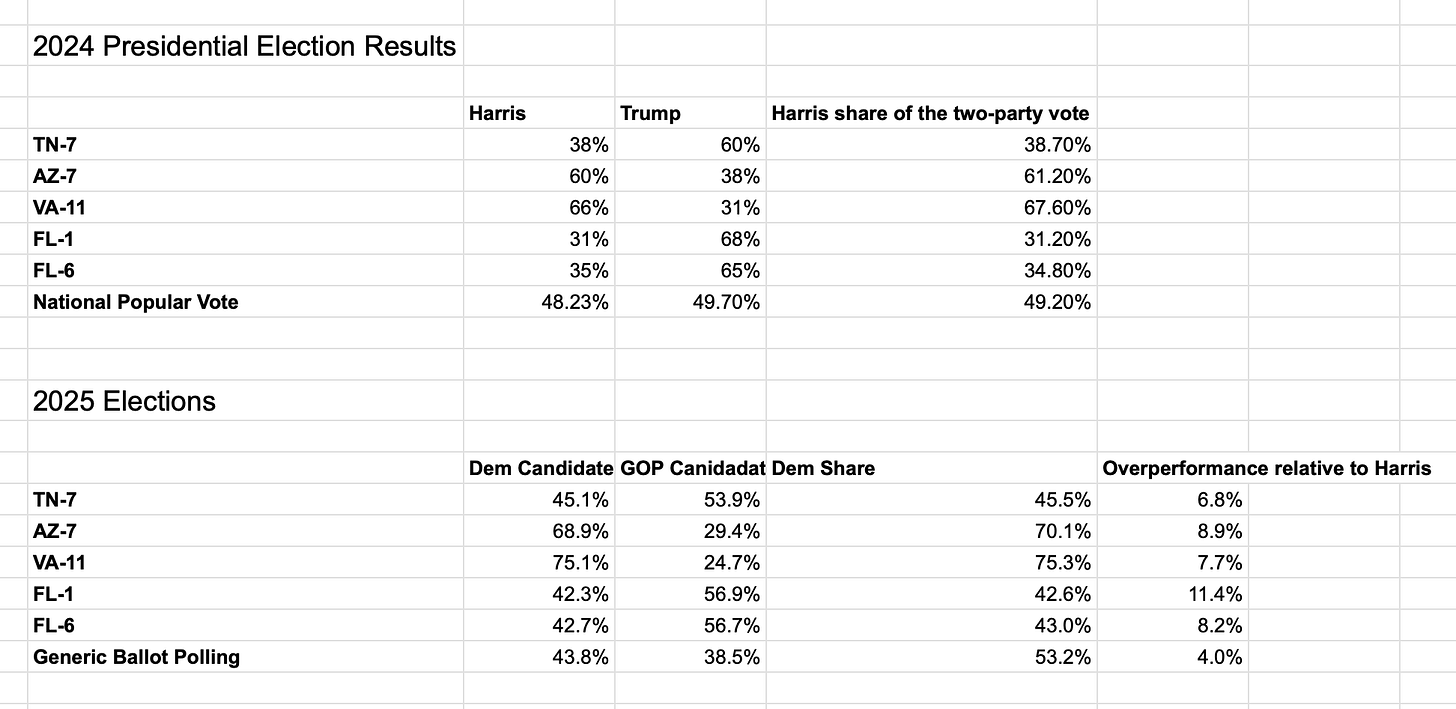

Still, to an extent, that whole conversation is beside the point. What’s important about the race is that Aftyn Behn lost by nine percentage points in a district that Kamala Harris lost by 22. And what’s particularly significant about that is that this election attracted millions of dollars in ad spending and interventions by both Donald Trump and Kamala Harris.

We know that Democrats now dominate with the highest-propensity voters and thus have the opportunity to score big overperformances in elections that nobody is paying attention to. That’s why Democrats did so much better in November’s obscure Georgia utility regulator races than they did in the higher profile gubernatorial contests in Virginia and New Jersey.

The Tennessee special election wasn’t like that.

Democrats do seem to have benefited from differential turnout, but it was high turnout overall. And more to the point, turnout isn’t purely exogenous. This ended up being a fairly high-salience race. Republicans spent meaningful amounts of money trying to both motivate their base and persuade persuadable voters. There was a House special election in Florida back in April where Democrats lost by 15 in a seat that Harris lost by 37. The key thing about that race is that it was barely contested by either side because the district is so uncompetitive. The scale of Democratic overperformance in this race did convey information about something, but it wasn’t a good model of what a real election would look like.

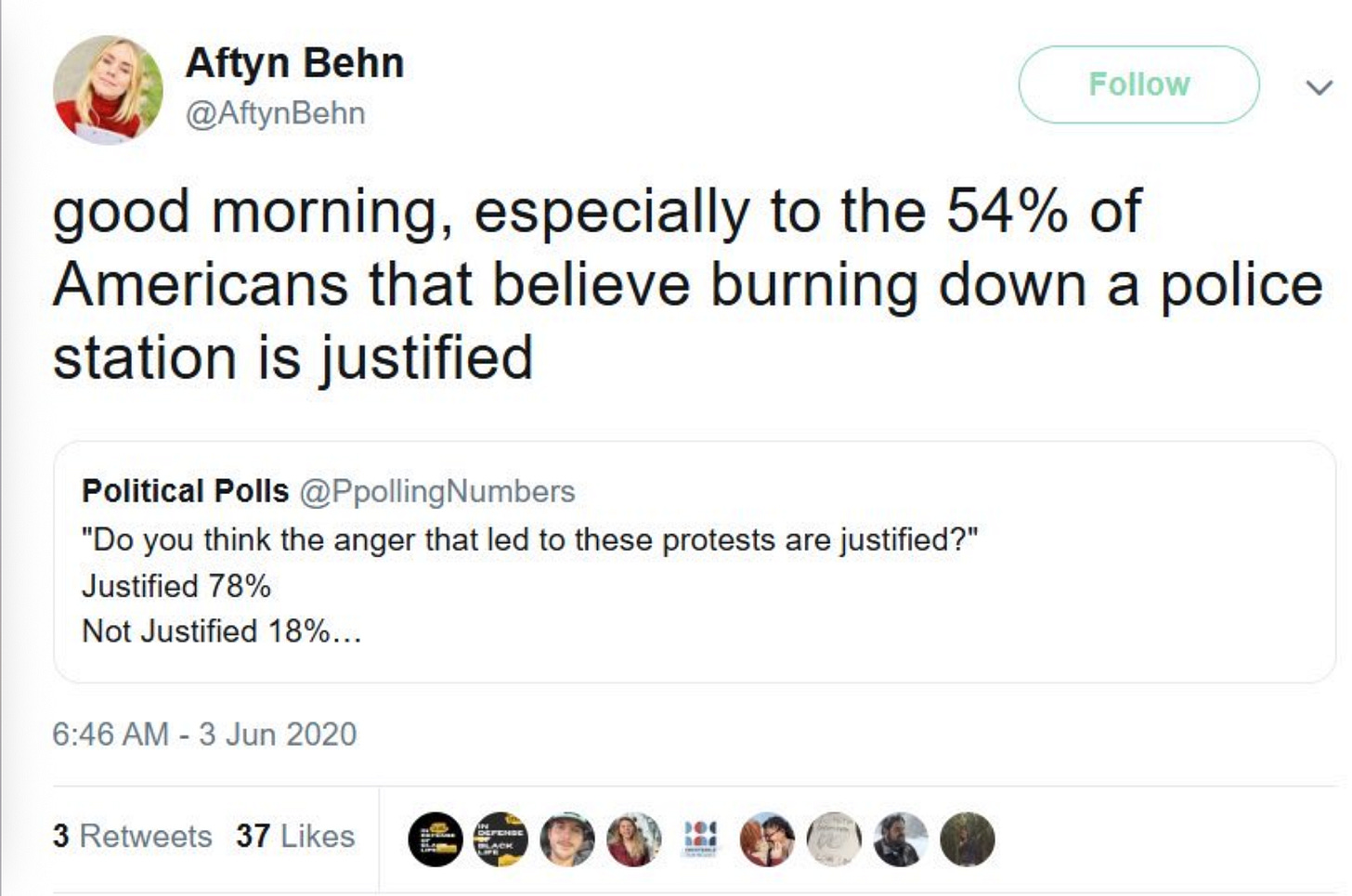

The Tennessee special, by contrast, was a real election with real budgets and some earned media attention. And Behn, though by most accounts a charismatic person and effective public speaker, was a genuinely terrible candidate for the district. Unlike Zohran Mamdani, she declined to disavow earlier support for defunding the police and had a record of inflammatory statements that made it clear she wasn’t just talking about hiring more social workers.

If Democrats can put up 13 points of overperformance in a meaningfully contested House race with a candidate who is terribly positioned to win crossover voters, that suggests Republicans are in deep trouble.

Deep enough to realistically put a Senate majority within reach, if Democrats come up with good nominees.

Let’s do some math

Here’s a little table I threw together that shows (on the left) 2024 presidential election results in the five House seats that had special elections in 2025 and then the special election results in those seats. I also threw in the national popular vote from 2024 and the current generic ballot polling average from Decision Desk for good measure.

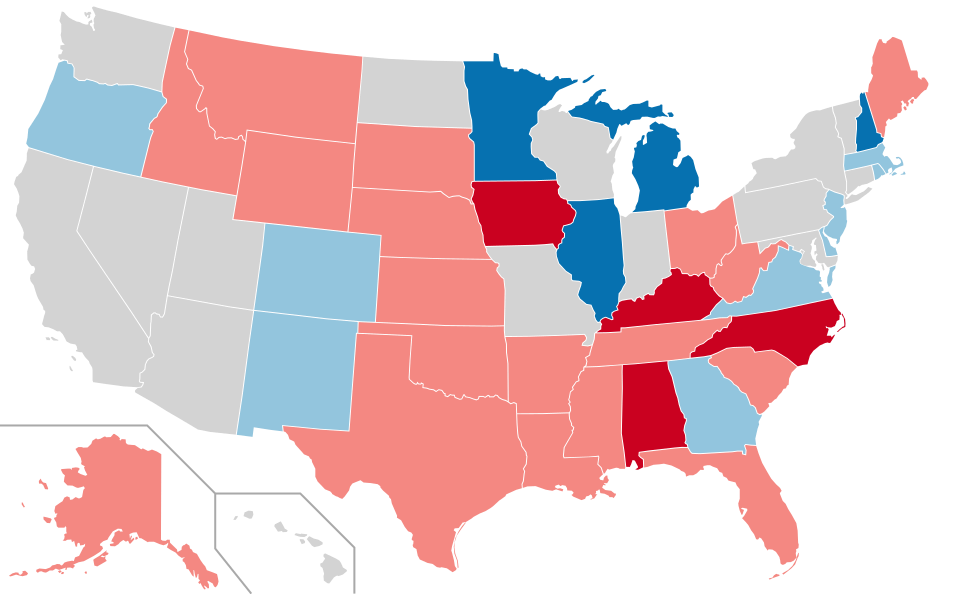

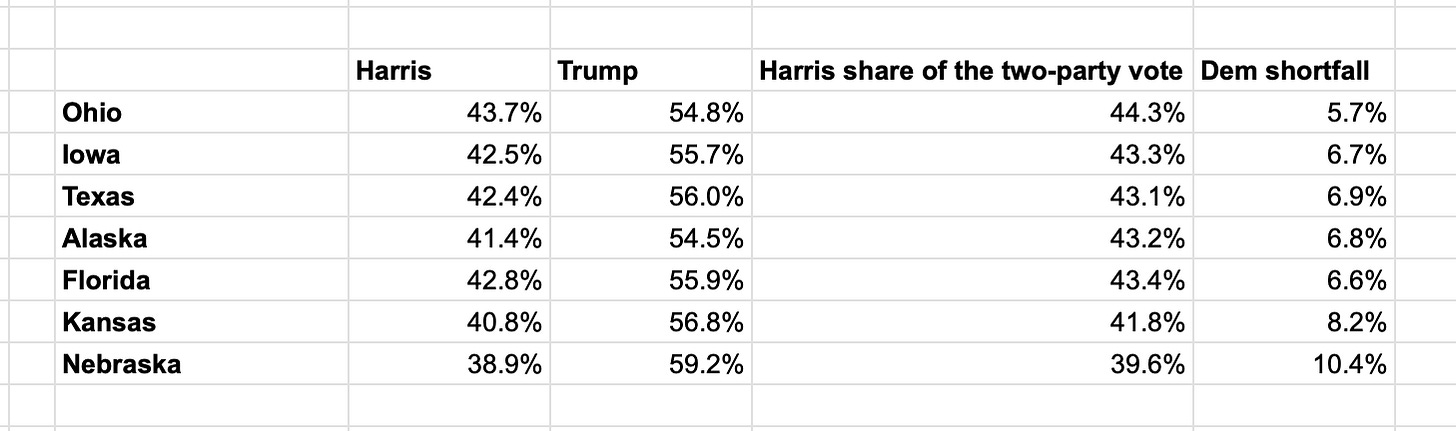

Now here’s a table looking at the 2024 election results in seven states with Senate elections, and the scale of the Democratic shortfall in each state. You can see that if you project the generic ballot forward, Democrats are falling short in all of these states. But if Democrats can overperform by as much as they did in Tennessee, they have a fighting chance in a bunch of them.

A four-point gain relative to Harris would be good enough to flip North Carolina (and Democrats have a very strong candidate there), at which point attention would turn to the messy situation in Maine. I think that if Dems flip two Senate seats and take the House, there will be a strong inclination to declare victory. If they flip North Carolina but lose in Maine, there will be bitter factional arguments about the outcome of the Maine Senate primary.

But that’s all misguided.

If you take the MAGA threat to democracy seriously, you need to win the Senate.

If you have any progressive convictions at all on any public policy issues, you need to win the Senate to pass bills.

If you want to win the Senate, you need to be competitive in states that Trump won as handily as he won Texas, Alaska, and Florida.

If Democrats do four points better than Harris did and we end up talking about Maine, that is a failure and they are not doing good enough.

Conversely, the message of the Tennessee special election should be that even though it’s tough to win in Iowa, Ohio, Texas, Alaska, and Florida, it’s not impossible.

Democrats secured roughly the level of overperformance that they would need in a reasonably high-salience race, and they did it with a candidate who had some pretty big flaws. In four other House special elections with lower salience but better nominees, Democrats put up the numbers they would need to carry those states. And the good news about the generic ballot is that, while it’s not currently good enough, the historical trend is for things to get worse for the president’s party during the midterm year. It’s not inevitable that the generic ballot will converge to the kind of numbers we’ve seen in actual elections, but it’s certainly plausible and in line with history.

That being said, what I want to see here is optimism about the Senate rather than fatalism in the face of a “bad map.” The map is bad! But the point I’ve made over and over again is that the map doesn’t get particularly better in two or four years. The Democratic Party has just positioned itself in a way that all the maps are bad and it needs to take steps to change that.

And when I say optimism, I don’t mean complacency.

One concern I’ve developed about recent American politics is that, while molecules don’t read chemistry papers, politicians and political operatives do read political science. They may look at findings like “the generic ballot normally moves against the president’s party over the course of the midterm year” and then just assume that it will happen.

These are observed empirical regularities, though — not laws of nature. From what we can tell, campaign effects are normally small but that’s in a context of both sides trying to run good campaigns. If one party just stopped campaigning, I bet the impact of the other would be large. By the same token, we know that in the past, opposition parties have managed to move the needle over the course of the midterm year. That should confirm the assessment that winning the Senate is realistic, but it means Democrats need to think seriously about the map and try hard to actually do it.

Senate races are harder than special elections

Actually trying starts with recognizing that even though TN-7 had high salience and high turnout for a House special election, it still didn’t have the kind of salience you would expect in a typical Senate race. In particular, the election didn’t get much media attention until the very last minute. In a real election, the weak spots of both parties’ candidates are going to be aired much more extensively. And having a bad nominee in TN-7 almost certainly wasn’t the difference between winning or losing, because the district was just too red.

But in the key Senate states, that’s not the case — these are actually within reach.

In Ohio, Democrats are going to run back Sherrod Brown rather than try a fresh face. That’s perfectly reasonable, though I hope Brown will remember facts that he used to know about the Ohio electorate — for example, fifteen years ago he positioned himself to the right of Obama on climate. That was in a context where Obama had won Ohio and was still vocally in favor of an “all of the above” approach to American energy. A Sherrod Brown who knows what the 2010-vintage Sherrod Brown knew about Ohio, energy, and economic populism could potentially win Ohio even in a tough year, to say nothing of a friendly one. But you need to actually get that version of Sherrod Brown, not the one who convinced climate-focused donors that all it takes to win is a rumpled suit.

In Texas, Colin Allred dropped out of the race this week, setting up a head-to-head race between James Talarico and Jasmine Crockett. Talarico is an unproven commodity, but his ability to win over Joe Rogan is impressive and he has high favorable ratings thus far. When it looked like it was going to be him versus Allred, my concern was that a contested primary would push two smart politicians both too far left to win in Texas. Now I’m really afraid Democrats are going to blow this. Crockett is a massive small-dollar fundraiser and a crowd-pleasing guest on MSNBC and other base-oriented media, but that’s not a good resume for winning a Senate race in Texas.

In Iowa, as I’ve mentioned before, I like Zach Wahls a lot and if you take the special election precedents seriously, I think you could imagine him winning a Senate election. But Josh Turek has a demonstrated track record of overperformance in state legislature races that, in a favorable national political climate, leads me to believe his odds are genuinely over 50 percent if he gets the nomination. Nathan Sage is too left-wing.

In Alaska, there’s an ongoing effort to recruit Mary Peltola, who would clearly be a great option. Word on the street is she may be more inclined to run for governor, a race where it’s easier to divorce herself from the national party. I think the national party should take this seriously, and really ask themselves whether the juice is worth the squeeze in terms of losing winnable voters in Alaska by insisting on large-scale federal interference in management of Alaska’s natural resources. Reasonable people can disagree about how to strike the balance between nature preservation and mining, and I think Democrats should defer to Alaska’s actual elected officials about this instead of treating the state as a remote colony to be run for the benefits of green donors. It would help win a Senate seat, it would help appeal to Lisa Murkowski, and it would be complementary to winning in Texas and Ohio.

In Kansas and Florida, I’m told that Democrats basically don’t have candidates. That’s a shame, both because these states are conceivably winnable and also because I think it’s a reminder that the whole Democratic Senate strategy has become excessively reliant on the idea of recruiting unicorn candidates. I don’t think it’s unknowable what a winning candidate profile in Kansas might look like. Even if Laura Kelly and Sharice Davids don’t want to take a crack at the race, any candidate (some mayor, a pro-choice farmer who’s mad about tariffs) could speak to the two of them and assimilate their knowledge. They’d have to say clearly that they plan to be an independent voice and a lot more moderate than most Democrats, but that’s not undoable.

Florida … is less clear. To me the autopsy exercise the Democratic Party and the progressive movement should do that has never been done is the “what went wrong” in Florida bit. Looking ahead from 2012, this is the place where the party’s bet on demographic change and concern about rising sea levels and hot weather should have paid off. I don’t have a pet theory about this. I’m just saying, this state is a lot more winnable than TN-7 was. Try to find someone!

In Nebraska, Dan Osborn is running once again as an independent. I think that’s great; he just needs to really put some meat on the bones of the whole “I’m not a Democrat” thing.

It takes discipline to win

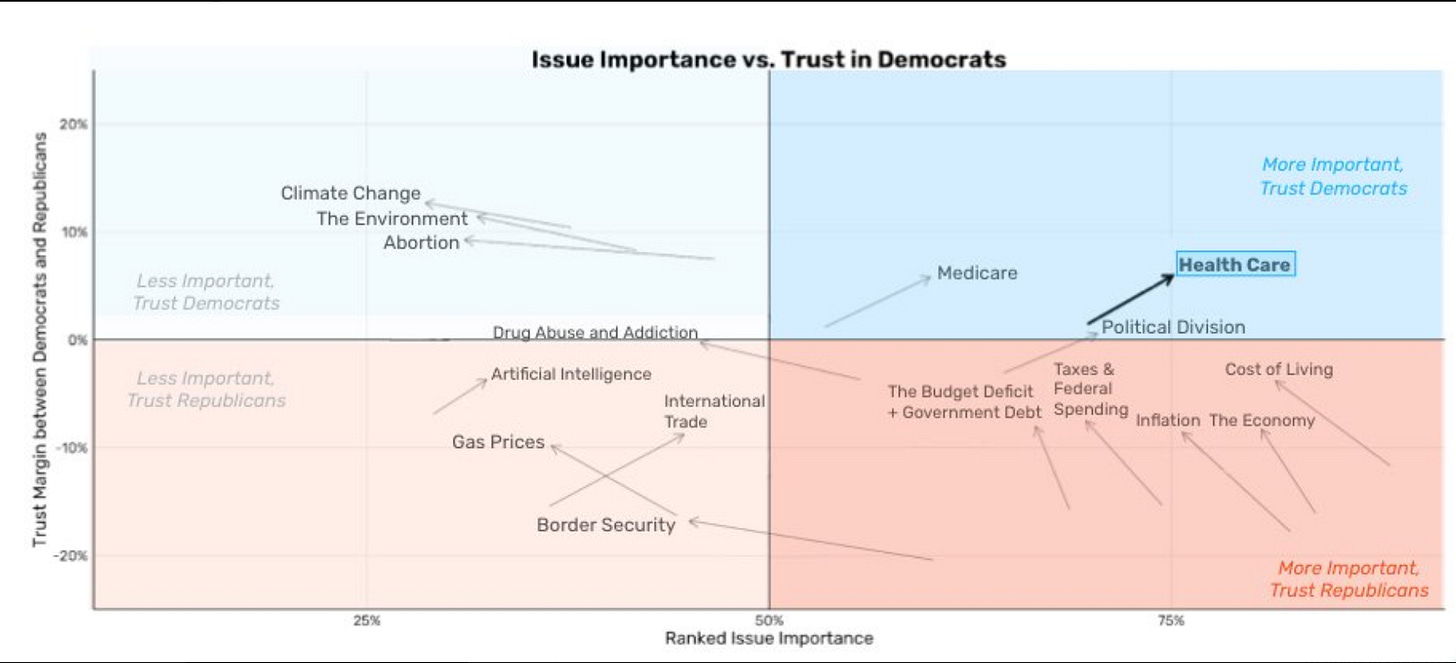

If you want to understand why Democrats have a shot at winning in unlikely places, this David Shor chart showing thermostatic public opinion at work is incredibly useful.

It’s an update of work Blue Rose Research did a bit over a year ago that showed Republicans had a daunting trust advantage on most of the issues that voters saw as most important. But over the course of a year of governing, three bad things happened to Trump. One is that on his best issues, including border security and gas prices, people care less than they used to. Another is that on issues like cost of living, the economy, and inflation, people still care a lot but the G.O.P. trust edge is collapsing. And the third is that Democrats have succeeded in getting people to care more about Medicare and health care while increasing their issue advantage.

I think the moral of this story is pretty clear: Democrats — not just those in tough races, but as many Democrats as possible — need to portray themselves as a political party that is obsessed with health care, the cost of living, and economic growth. That means prioritizing those issues in a real way when faced with a tradeoff on climate change and the environment.

But it also means consistently dragging media attention back to those topics, even though you and I both know that in their heart of hearts Democratic Party elites are deeply angry about Trump as a violator of procedural norms of constitutional democracy and a fomenter of cruelty toward immigrants and other vulnerable people.

That doesn’t mean no one should ever mention these other issues.

Topics of corruption, for example, very naturally lend themselves to the argument that Trump and his band of cronies are enriching themselves rather than enriching you. And in a big picture sense, part of the point of democracy is that in a functioning democracy the rulers need to care about your economic interests, and Trump is degrading those accountability functions because he only cares about his interests.

Still, while I’m not going to tell you that murdering Venezuelans or promising ethnic cleansing of Muslim immigrants is exactly genius politics, it’s clearly better politics for Trump to have these topics on the front page than the fight about Affordable Care Act subsidies.

If you actually want to check Trump’s abuses of power, rather than talk about checking them, then by far the best way to do that is to win a Senate majority, which can halt the MAGA-fication of the judiciary and put real pressure on nominations throughout the executive branch. And when you’re trying to think about what can win over voters in deep-red terrain, it’s worth thinking not just about polling on specific issues, but about the macro structure of the argument in American politics.

When push comes to shove, Trump is happy to concede the idea that he is indifferent to the welfare of foreigners — whether that’s immigrants or Ukrainians or AIDS patients cut off from PEPFAR. He is not happy to concede that Democrats have better policies for the core economic interests of the typical American. His willful indifference is more morally scandalous than his bad opinions about health care policy. But Trump and Stephen Miller and J.D. Vance and Pete Hegseth really are prepared to concede that point. They revel in it even.

And it’s gross! I genuinely don’t understand how they purport to be Christians while behaving this way. But in political terms, it’s important to focus on trying to win the argument they’re not prepared to concede. The bulk of the persuadable electorate is probably people who thought of Trump as a businessman who is “good at the economy” and are now having doubts.

Democrats’ main priority has to be amplifying those doubts while addressing the public’s doubts about their own priorities.

Indeed this got my attention when I saw 9pts miss, by a Lefty-Left candidate in that kind of district: 'If Democrats can put up 13 points of overperformance in a meaningfully contested House race with a candidate who is terribly positioned to win crossover voters, that suggests Republicans are in deep trouble.'

The chart on movement of Trust re Cost of Living is quite meaningful so @ ' I think the moral of this story is pretty clear: Democrats — not just those in tough races, but as many Democrats as possible — need to portray themselves as a political party that is obsessed with health care, the cost of living, and economic growth. That means prioritizing those issues in a real way when faced with a tradeoff on climate change and the environment.'

Seems spot on.

Being mad about Democracy should mean being serious about reflecting on what it takes to win in said democracy, not intellectualising about it but taking lessons on what's needed to flip votes to get the power to protect democracy. The 1930s showed similar lessons, masses don't value democracy as democracy [good or bad they don't overall] they value pocket-book issues.

Trump's speech yesterday where he went off the rails apparently - flipping back to immigration and anti-foreigners rambling when he was supposed to talk Affordability (i.e. pocketbook issues) shows the vulnerability - he's got no 2nd script really and under stress he retreats to where he sees accolades. Suggests rather strongly that like the Biden Admin / Proggy Left of Biden era, Trumpies are going to make the mistake of thinking that they can emphasize Their Points and ignore / downplay / argue away Cost-of-Living.

Here's a simple way to put it: Democrats should want winners, and anyone who can't put together a plan to win should be branded as losers. They can try to say that they're losing for a great cause, such as staying ideologically pure, but they're still losers. Call out the losers as such, set them aside, and put some people in that can be winners.