When people don’t vote, Democrats win

Everyone needs to learn the new politics of turnout

Back on August 5, there were two special elections for state legislative seats.

Democrats won them both. In Delaware’s House District 20, the Democratic candidate narrowly won a seat that Kamala Harris carried by a 54-45 margin — a poor showing for Democrats, even though they won the seat. The other race was in Senate District 4 in Rhode Island, a 55-44 Harris district. And here, Democrats won by a whopping 83-16 in a massive overperformance.

We can’t learn much from any one special election race, since there are dozens of idiosyncratic factors at work. But special elections in the aggregate do convey some information about the national political climate.

So far in 2025, Democratic candidates in special elections are running 15.5 points ahead of Kamala Harris and 11.1 points ahead of Joe Biden’s (much stronger on average) baseline from 2020.

This is telling us that the national political climate not only favors Democrats, as you would expect for the out-party under an unpopular president, but massively favors them. Slow Boring readers know I’ve been dooming about the upcoming Senate races, but if Dems can actually run nearly 16 points ahead of Harris, then Ohio, Texas, Iowa, Florida, Alaska, and potentially even Kansas are all on the map. And that’s exactly what the party needs to meaningfully contest for a Senate majority, check the MAGA-fication of the federal judiciary, and actually make policy change in 2028.

So is everything fine? Am I totally wrong about the need for ideological adjustments?

This is the kind of argument that purveyors of “hopium,” like Simon Rosenberg and Tom Bonier, offered in the 2024 cycle. Across 2023 and 2024, Democrats beat Joe Biden’s benchmarks by 3.5 percentage points in special elections. Had Democrats performed that well in November, Harris would have added North Carolina to Biden’s hefty electoral vote haul. Bob Casey would have been re-elected, and the Senate races in Ohio and Montana would have both been razor close.

Why didn’t the national climate, as measured by special elections, translate into November reality? It’s pretty simple, as my friends in the analytics community and I explained: In a change from the Obama era, Democrats are now the party that performs best among the people who are most likely to vote.

This gives Dems an edge in low-turnout special elections, so while these elections do offer some real information about the national environment, you can’t just copy and paste the results.

This is on some level a boring technical question with no ideological or policy implications. But on another level, it’s a big deal. Having the likelier-to-vote coalition is good, it’s a strategic advantage for Democrats that is keeping them in the game, despite other problems. But it’s also a potential source of complacency, as the hopium controversies of last year showed.

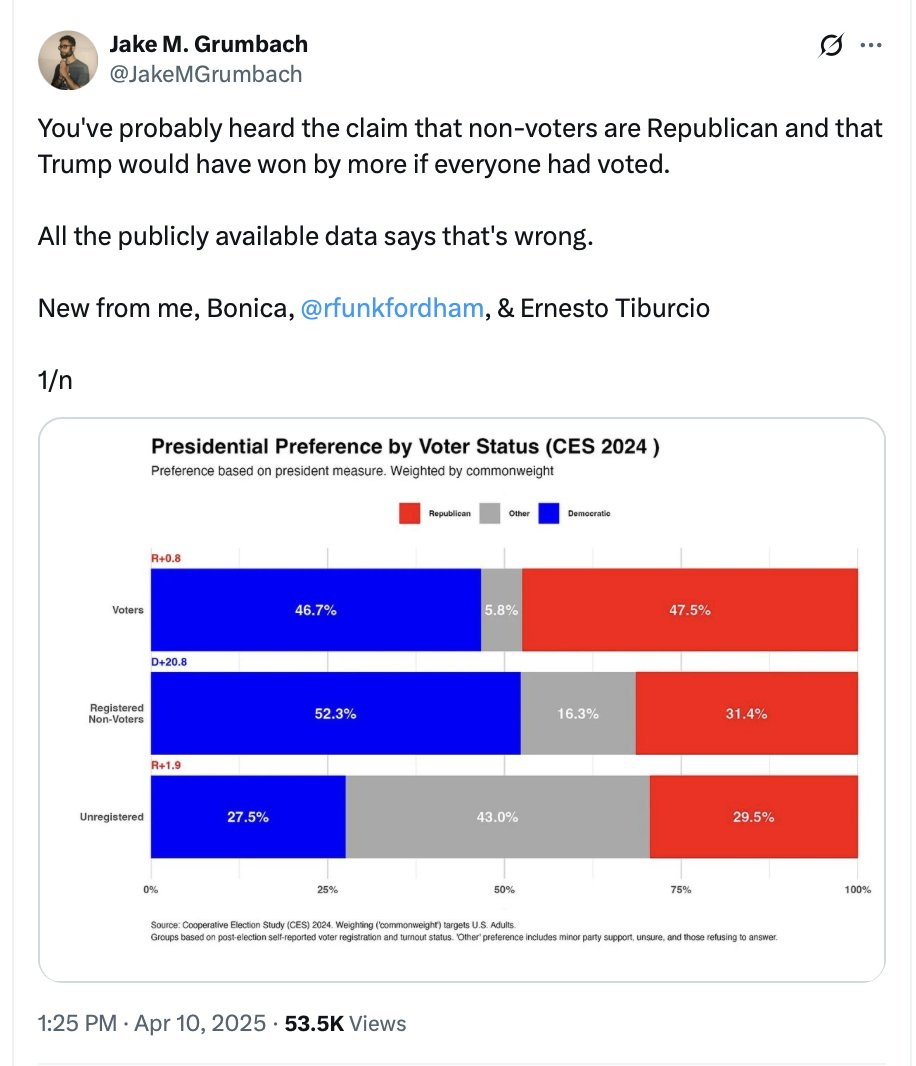

So I think it’s significant that some of the most prominent purveyors of hopium have largely thrown in the towel. New information shows definitively that the people who didn’t vote in 2024 are an even more Trump-friendly group than the people who did vote, and that untargeted voter registration and mobilization schemes are likely to help Republicans rather than Democrats.

I want to walk through this data and, more importantly, to walk through what it implies for some ongoing controversies. Because while I think it’s good that people are coming around to the truth on this, I think almost everyone is underreacting to its implications.

Nonvoters now favor Trump

The fact that propensity to vote is now correlated with opposition to Donald Trump and the MAGA movement is not news to Slow Boring readers. But when David Shor presented this information on the Ezra Klein Show back in March, he got significant pushback from some progressive academic political scientists (yes, the same people claiming it’s not knowable whether moderates are better at winning votes) who were citing early Cooperative Election Study (CES) data.

Notably, though, once the CES updated the weights to rely on a validated voter file, this result changed, and these researchers now agree with Shor’s survey that nonvoters were more Republican-leaning. Disagreement about magnitude remains, and Jake Grumbach, to his credit, did admit he’s changed his mind about this, but I’m not sure that he’s reconsidered the larger point that the entire post-2012 leftward pivot of the Democratic Party was based on the theory that this was a good way to mobilize additional voters and therefore win more elections.

From the standpoint of doing academic work and writing articles, it’s useful to have publicly available data and transparent methodology that you can use to make comparisons across time. Doing research based on proprietary methods from a private firm like Blue Rose that didn’t exist in the recent past is problematic in ways I’ll happily admit to.

On the other hand, from the standpoint of doing academic work and writing articles, it’s sort of perversely unimportant whether the surveys are accurate. This means that if traditional survey methods become less effective due to declining response rates and maximally accurate surveys become more expensive and rely on novel methods, academics will face considerable pressure to stick with legacy methods. I would implore everyone who is considering wading out of the ivory tower to tackle questions of interest to practitioners to think about this point. At the time of the original Shor-Grumbach dispute, after all, we already knew about Democrats overperforming in low-turnout special elections, and we also knew that Trump’s coalition had become younger, poorer, and less educated, which are all demographic correlates of low-turnout.

Democrats need to change their tactics

One implication of Democrats being less likely to vote relates to some pretty banal aspects of tactics and political mechanics. My friend Aaron Strauss does analytic work to help Democrats win, and he’s been preaching for years that donors need to become more skeptical of non-partisan voter-registration drives. Donors like to fund these because they can make tax exempt contributions, and it sounds a lot more high-minded than investing in partisan politics, even while de facto advancing partisan goals.

But the new turnout climate and new registration data is causing Strauss’s long-time antagonists to change their tune on this:

Tom Bonier, one of the Democratic Party’s leading experts on voter-registration trends, spent much of 2024 downplaying the seriousness of his party’s registration woes. He has now come around.

“I was wrong,” he said in an interview.

Unfortunately, turning conventional wisdom around is hard. Anyone working at or running an existing voter-registration program has an incentive to dissemble about this. And we also just have a lot of lagging indicators.

I remember going to see a movie shortly before the 2024 election. Before the movie was an ad in which celebrities urged people, in a totally nonpartisan way, to vote. I don’t know exactly what these celebrities’ political views were, but given the broad political tendencies in Hollywood and the demographics of the actors, I am pretty sure they mostly wanted you to vote for Harris. But of course they didn’t say that — I think they just assumed that encouraging people to vote would be good for causes that they believed in.

That conventional wisdom was true during the Bush and Obama presidencies.

At that time, Democrats were the party that performed best among voters with lower levels of interest in and attention to politics. Democrats had generally “good vibes,” and Barack Obama was a popular and charismatic pop cultural figure.

But Democrats struggled in low-turnout special elections and in midterms when turnout dropped relative to presidential races. Back then, Democrats also weren’t all that worried about “misinformation,” because people with low levels of political knowledge were a Dem-leaning constituency. This Obama-era dynamic made it easy for people to be generically pro-participation, pro-democracy, or just generally rah-rah about civic engagement while in practice trying to help Democrats.

Now, word really needs to get out, not just to professional political operatives but a broad universe of politically engaged people, that generic pro-participation stuff is likely to help Trump.

That doesn’t mean Democrats shouldn’t register voters or try to increase turnout. But it means they should do so in targeted ways. Even if the pool of non-registered African Americans is a lot redder than the pool of high-propensity Black voters, it’s still going to be a Democratic-leaning group. Women on college campuses are a no-brainer target. People smarter than me can come up with more ideas. But the point is that unless you know who you’re targeting for this stuff, you’re probably reaching checked-out anti-system people who don’t love Trump (if they loved him they would vote without being pushed!) but on balance like him more than his critics.

But beyond tactics, assimilating this point also has ideological and policy stakes.

A good time to rethink voting policy

Trump hates mail-in voting because he’s embraced various conspiracy theories about the 2020 election. Democrats like mail-in voting in part because of a principled desire to make voting easier, but also because of their belief that making voting easier and boosting turnout will be good for them electorally. That latter claim probably isn’t true anymore. I’m not going to say that Democrats should cynically go out of their way to make voting inconvenient. But if Democrats take the House in 2026, they’ll find themselves needing to engage in bipartisan dealmaking. If you end up needing to give Trump a win on something in a horse-trade, why not give him a win on something like this?

Similarly, Democrats tend to oppose strict photo ID requirements for voting. That’s a pretty unpopular stance that probably costs them at least a few votes. Is the juice worth the squeeze in a world where increasing administrative burdens on voting probably hurts Republicans at the margin? Why fight to the death on this?

There are also a lot of smaller decisions. Early in Trump’s second term, I identified the Wisconsin Supreme Court race as an important opportunity to defeat Elon Musk’s money and somewhat demoralize him about politics. We won that fight, and one thing that made it winnable was that Wisconsin holds its judicial elections on a random Tuesday in April. If Democrats had their Obama-era coalition, it would make sense to try to change stuff like this to happen on normal election days in November. But with Trump now dominating low-propensity voters, holding elections on unusual days helps Democrats.

It’s also worth recalling that Democrats’ post-2012 leftward ideological repositioning was driven in large part by the belief that it would increase turnout.

This is what I’ve called in the past progressives’ mobilization delusion, and it’s sadly tenacious. Back in those days, though, even I agreed that increasing turnout would help Democrats win — we were just disagreeing about whether being left-wing would advance that goal.

Today, though, it no longer seems like boosting turnout is even desirable. And a lot of folks who have more or less given up on the turnout-related arguments of 10 years ago haven’t actually revisited their thinking about the electoral wisdom of the party’s leftward moves.

My 2¢ is that back when I was 17-18 I wrote a series of articles for my high school newspaper arguing for reforms that would make it easier for more people to vote. At the time I thought this would probably help Democrats. As Matt points out that’s not true anymore. But I still think it should be easier to vote and I want more Americans to vote, and if that helps Republicans then so be it; it’s on us as Democrats to go back to the drawing board and work out a winning message.

It’s a bit orthogonal to the piece, but given Matt’s intro I feel compelled to say: Just as it’s wrong to project from special elections to a high-turnout presidential race, it’s equally wrong to imply (as Matt seems to do) that 2026 will look like 2024 if the Dems don’t make ideological adjustments.

Dems will do well in 2026, even without making ideological adjustments, thanks to thermostatic public opinion and their more-likely-to-vote coalition. This is honestly why I’m not too worried about whether Dems do or don’t “moderate” in the immediate term.

IMO, the bigger argument / challenge is going to be between 2026 and 2028, when certain people will attribute 2026 success (assuming it happens) to the positions the Dems did or didn’t take rather than external factors. And when it does seem likely that moderating helps in a presidential election year.