A bolder vision for American energy

You can’t “electrify everything” without more electricity.

I had an odd dispute with an energy policy wonk a few months ago in which I was saying that electricity is expensive in California — meaning that the price of electricity is high — and he was saying that it’s cheap, by which he meant the average household’s monthly electricity bill is not particularly high.

His point is true because the average California household uses a below-average amount of electricity compared to residents of other states. That’s in part because of energy efficiency standards, but it’s in part a function of weather and infrastructure.

They don’t use a lot of electricity for air conditioning in California because in large swaths of the state it’s generally not that hot in the summer. In the South, where you might think the mild winters would balance out the incredibly hot summers in terms of relative energy use, people tend to have inefficient, “good enough” electric resistance heaters for the occasional cold snaps (compared to places where it’s really cold, where people tend to burn gas or oil for home heat). So even though electricity is much cheaper in Alabama than in California, the average monthly electricity bill in Alabama is a lot higher.

Why does this matter?

Well, it’s a reminder that influential elements of the environmental movement are driven by their roots as a conservation movement. The core desire expressed here is to shrink the human footprint: to use less energy, build less stuff, and live more humbly and in harmony with a somewhat superstitious conception of “nature.”

You also see this in the Sierra Club’s strange journey on immigration, which they used to be very hostile to because of their degrowth values. They eventually dropped their anti-immigration stance and later became good progressive allies to the immigration advocates because of the awkward coalition politics.

But the Sierra Club and many other environmental groups didn’t drop the degrowth ideology.

They often say that they’ve dropped it, and I think they sometimes genuinely believe they’ve dropped it. But whenever the rubber hits the road, they are fundamentally more interested in learning to get by with less than in developing abundant clean energy.

And this is popping up in a serious way as the movement wrestles with rising electricity demand. Building a clean energy economy is going to require huge amounts of new electricity. That means tons of new generation and tons of new transmission infrastructure — gargantuan projects that will allow us to use electricity to power our cars, to cook our food, to heat our homes, and maybe eventually to ship our freight or provide heat for industrial purposes.

But instead of focusing on how to get all that electricity built as quickly and cleanly as possible, the greens want to impose tighter price controls on utilities, minimize infrastructure investment, and meet household energy needs with rationing.

The long war on utilities

Almost1 no one thinks that market competition works for electrical utilities. There are too many complexities involving public rights of way, and it’s too expensive to maintain multiple overlapping sets of transmission and distribution infrastructure that compete with each other.

There are a few ways to handle this non-competitive situation. One is public power, like you see with the Tennessee Valley Authority.2 Another is electric co-ops, of which there are many in the United States, but they’re generally small. A third is a regulated utility, where a private company acts as a monopoly provider but its rates are regulated by the government.

The utility model itself comes in two forms: “vertically integrated,” where the utility also owns power plants (this is most common in the Southeast), and “deregulated,” where, despite the name, the utility is highly regulated but purchases its actual electricity at market prices from competing generators. In both the vertically integrated and deregulated models, though, the utility’s profit margins and rate of return are capped.

What’s not capped is that if you build more infrastructure and sell people more electricity, you make more money. The point, traditionally, of utility regulation was to make electricity abundantly available. You prevent the utility from gouging its customers, but you encourage it to sell them more electricity.

Environmentalists have always hated this model, because they don’t think we should sell people more electricity. Amory Lovins and the Rocky Mountain Institute, for instance, spread the idea that the cheapest and greenest kilowatt-hour is the one you never use. Environmentalists want to promote conservation. They acknowledge that people need electricity, but they think that’s bad. If everyone can switch to different kinds of light bulbs so they don’t need as much electricity, that’s the win. They think the point of utility regulation should be to provide people with an adequate amount of energy to get by. That means there should be a positive financial incentive to get people to use less, rather than a positive financial incentive for the utility to build more and supply more.

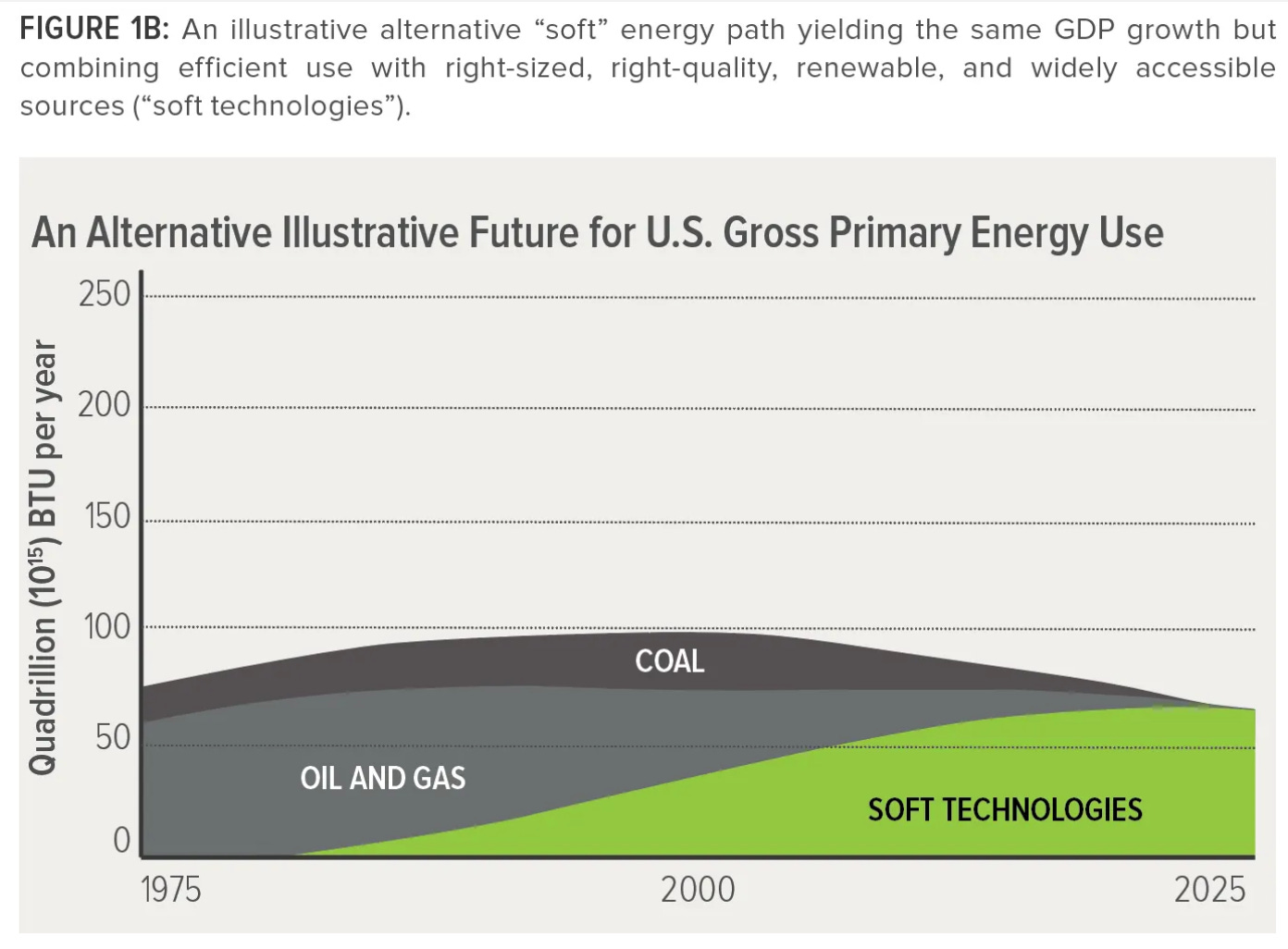

Lovins — regarded as an authority by the Natural Resources Defense Council, Sierra, and other major green groups — illustrates this well in his “soft energy path” charts. He envisioned replacing America’s level of 1975 energy consumption with a 100 percent renewable system that does not replace 100 percent of the 1975 energy. His view is that we should be substantially reducing per capita energy consumption as an integral element of the energy transition.

You can’t really make sense of anything these groups do without understanding that as the goal.

And of course it’s great to be less wasteful. But I think this is a fundamentally unappealing vision, which is why the groups that are promoting it tend not to state it as clearly as Lovins does. But with public anxiety about electricity prices rising, the opportunity has presented itself to kill two birds with one stone: if you can force utilities to accept a lower rate of return, you’ll address consumer demand for relief and achieve the long-term goal of handicapping energy infrastructure growth.

As you see greens try to address the political demand for affordability, keep your eyes peeled. There’s a big difference between an agenda to make energy more affordable through abundance and more affordable through rationing.

The soft path to rationing

Leah Stokes’s recent Atlantic article outlining ideas to make electricity cheaper is an example of both the agenda, and the tendency to rhetorically soft-pedal what the agenda actually is.

She writes that you could make electricity prices lower by cutting utilities’ rates of return, and that one benefit of this policy is that it would cause them to invest less.

Legislators could trim these profits directly by more closely aligning utilities’ guaranteed rates of return with their actual costs. Such adjustments could also limit utilities’ endless quest for more infrastructure.

I’m glad she said it so clearly here. Recently, Neale Mahoney and Bharat Ramamurti wrote an op-ed trying to convince people like me to worry less about price controls and see that those controls could be part of a one-two package of immediate consumer relief plus long-term supply-side measures.

And they definitely could be! But to understand the landscape, you have to understand that Stokes (a favorite at Sierra, League of Conservation Voters, Evergreen, and other mainstream green groups) doesn’t see the anti-supply impact of price controls as an undesirable downside — she sees it as a benefit. In their view, utilities are problematically overbuilding infrastructure, and we need to cut their rates of return, not just to save consumers money in the short term but to slow down utilities’ pace of investment.

Stokes offers two other ideas to make electricity cheaper. One is to take the portion of infrastructure costs that can be plausibly related to climate change off the ratepayers’ books, and instead allocate the blame for them to fossil fuel companies who will then be charged a fee. This seems like an awfully roundabout way of saying “do a carbon tax,” which is a fine idea, but it isn’t going to make electricity cheaper.

Then last but not least, she wants utilities to vary their pricing by the time of day.

In places with a lot of solar, including California, some installations are producing more energy than is being consumed, so some power is being wasted. If people shifted more of their electricity use toward the middle of the day, the grid’s overall costs would go down, because demand would decrease in later hours, when prices are the highest. And the easiest way to nudge people toward using that midday power is to make it cheaper — or even free.

Variable pricing seems like a reasonable idea to me (my uncle co-authored a paper advocating this a few years ago if you want a much more detailed version of the case), but it’s disingenuous to act like this is just going to be a case of cheap electricity in the early afternoon. To make this work, you need to have symmetrically higher prices at other times. More to the point, the green wing of the energy wonk community is suddenly buzzing in a frenzied way about responsive demand, as if this is some kind of magic alternative to major new capital investment, in a way that doesn’t make any sense to me.

Imagine if you electrified everything

A tell here, in my opinion, is that these takes often emphasize the question of data centers as drivers of new electricity demand. But imagine everyone decides tomorrow that AI is fake and nobody ever wants to build a data center again.

The climate movement itself has spent years prepping people to replace fossil fuels in cars, stoves, and furnaces with electricity. They want to ban gas leaf blowers and have people use electric ones instead. Electric boats aren’t quite ready for the mass market, but people are working on it. Electrifying heavy construction equipment, trucking, or freight rail seems further off, but one can imagine it happening and, again, it is specifically the climate movement that wants to do this.

Well, that means we’re gonna need a lot of electricity!

A small price nudge to encourage people to charge their electric vehicles at midday rather than in the evening is not going to replace the need for new infrastructure if you imagine a world where 100 percent of the cars are electric. And it’s definitely not going to work if you’re also electrifying home heating and larger and larger swaths of industry.

You of course do want to use infrastructure efficiently rather than inefficiently, but if you want to electrify large parts of the economy in the context of population growth and per capita G.D.P. growth, then you clearly want a lot more electricity infrastructure, not just better demand-management. That’s the appealing, optimistic vision of a modern dynamic approach to climate change.

But people who favor such an approach to climate change need to understand that the Stokes/Lovins vision that the green groups embrace is fundamentally different — they want decarbonization by rationing to avoid new infrastructure.

It’s important to be clear about the goal here because I think the progressive community raises reasonable questions about the whole regulated investor-owned utility model. There’s a lot to be said for the public power alternative!

But how we organize the utility sector is fundamentally less important than to what end we’re organizing it. If we replaced the investor-owned utilities of the Northeast with a T.V.A.-style agency, I think the goal should be to promote emissions reduction by making electricity cheaper and more abundant via a mix of natural gas, renewables, and transmission while hoping to participate in breakthroughs in nuclear and geothermal. And if we stuck with regulated utilities, I think the goal should also be to promote emissions reduction by making electricity cheaper and more abundant. We can debate the best policy mix to promote that goal, but we also need to debate the goal, and it’s one the green groups fundamentally reject.

They’d like you to see their posture as being more hardcore about climate change, but if you have a halfway realistic view of the politics, it’s not even that. People aren’t going to switch to electric cars and electric home heating if doing so raises their fuel costs, and you’re not going to have enough electricity to keep prices low in the context of electrification unless you build the infrastructure.

The case for ambition

Beyond the weeds of utility regulation, I’d like to motivate people to get off the soft path by reminding the world of the potential upsides of truly abundant energy.

One of the really big ones is the ability to do vertical farming.

This is a thing that people get excited about every few years because the benefits would be massive. Not only do vertical farms have a dramatically smaller geographical footprint than conventional farms, they are also wildly more resource efficient in terms of things like water and pesticides. The agriculture sector is responsible for dramatically more consumption of these resources than the overhyped data centers, but obviously people can’t just not eat food. The problem is that, offsetting all these benefits, a vertical farm would require lots of electricity to run, so it’s not within light-years from being cost-effective right now.

Similarly, if we could grow animal protein in a factory rather than raise livestock, we would achieve incredible ecological benefits and a massive reduction in cruelty. Powering such a factory with electricity is also in some sense more energy-efficient than growing crops to manufacture animal feed to give to chickens we then slaughter. But in a more literal sense, it would mean you’d need a ton of electricity.

It would also be nice to be able to actually do carbon removal to mitigate the harms of the global emissions overshoot that the world is all-but-certain to engage in. Perhaps this is doable, but it requires energy.

These somewhat utopian dreams are not policies for 2029 or even necessarily for 2050, but we ought to set high aspirations for a dynamic, cleaner, high-energy future. Sure, we should use our infrastructure as efficiently as we reasonably can. But the future ought to involve dramatically more electricity, which is going to mean dramatically more supportive infrastructure. A vision for utilities that doesn’t support that isn’t going to work.

I know some Cato guys disagree and I want to acknowledge you and tell you that I see you, but I’ll have to save that for another article.

Note that many environmentalists don’t like the T.V.A. because it replicates the large, centralized structure that they deplore about investor-owned utilities — in fact it’s even bigger and more centralized.

If the goal is to electrify everything in the United States and generate electricity solely through wind, solar, and batteries, we will have to mine more copper (and other metals) than has been mined in all of human history up till now. We can do it, but it will probably be even less popular, especially among groups like the Sierra Club, than nuclear and drilling for oil and gas. So to them, living like Noble Savages is the better alternative.

If the US deliberately cuts its electricity supply, that will (further) shift economic and political power to China, where environmental (and other) standards are lower. Feels like these orgs sometimes operate like there is only one country in the world.