There's plenty of water for data centers

Probably the last worry you should have about either water or AI

I’ve spent my whole life in the urban northeast, which is both soggy and light on water-intensive economic activity, so I haven’t spent a lot of time thinking about water use or water scarcity.

But large parts of the United States are arid or support water-intensive industries or both. Also, a lot of policy controversies relate to AI these days, as AI involves a lot of data centers, and data centers typically use water for cooling purposes. And the intersection of these issues has given us headlines like “‘Thirsty’ ChatGPT uses four times more water than previously thought” and “California wildfires raise alarm on water-guzzling AI like ChatGPT.”

This is factually accurate: If demand for AI grows, the AI sector is going to start using up more water.

But it’s easy to get lost in the sauce here. We’re not living on Arrakis, and residents of rich countries are not, in general, abstemious in their water usage.

Yes, you need water to drink or you will die. We also need water for crops or they will die, and if the crops die, you die too. Water is really important. We use it to cook, to wash dishes, and to wash ourselves. Water matters. But across the country, people are using water every day for things that have nothing to do with sustaining human life. They’re watering the lawn. They’re going to water parks or filling up a Super Soaker. If you go to a bar, water is used to make the liquor you consume there. And if you order a cocktail, it very well may be made by pouring a few different things into a vessel that contains frozen water, shaking it up, straining the mixed beverage into a glass, and then throwing the ice cubes away.

It’s easy to jump from “people need water or they die” to “here comes this evil corporation using water for greed!” But in fact, tons of water is being used for more frivolous (and less economically valuable) reasons than AI.

One of my favorite basic economics concepts is the water/diamond paradox. Adam Smith centuries ago observed that, “nothing is more useful than water, but it will purchase scarce anything; scarce anything can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.” Water was simply not scarce enough (especially in England) to be valuable, and diamonds were widely desired, despite not being very useful.

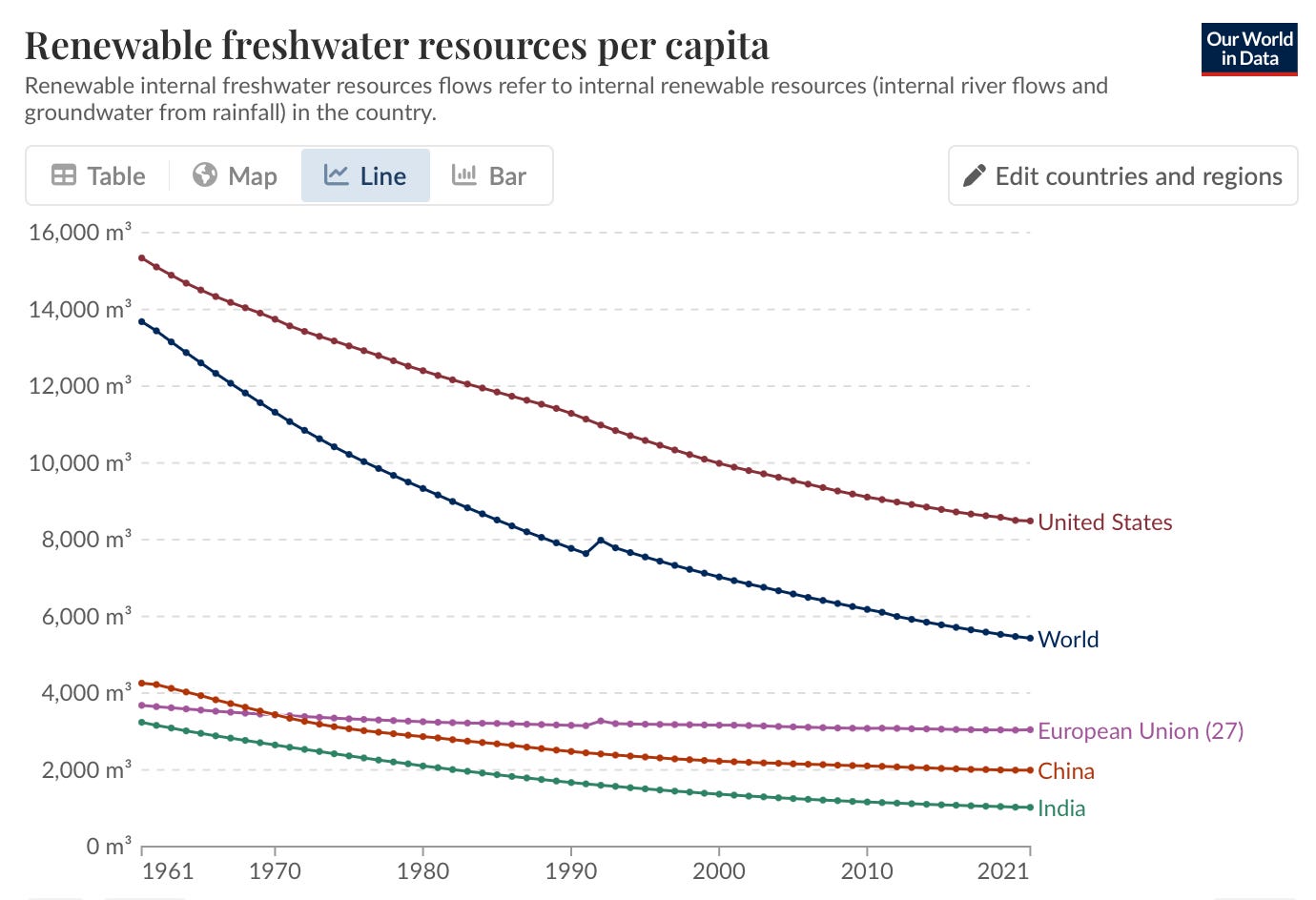

Since Smith’s time, we’ve managed to narrow the gap a little by coming up with industrial uses for diamonds and planting crops in Arizona. But I think the bottom line remains that water is not generally scarce and that coming up with new economically useful things to do with water is good. To the extent that there are problems with water usage, though, we want to make sure that we’re looking at it systematically, and ideally pricing water more rationally to ensure it flows to its most valuable uses.

Clean water is important

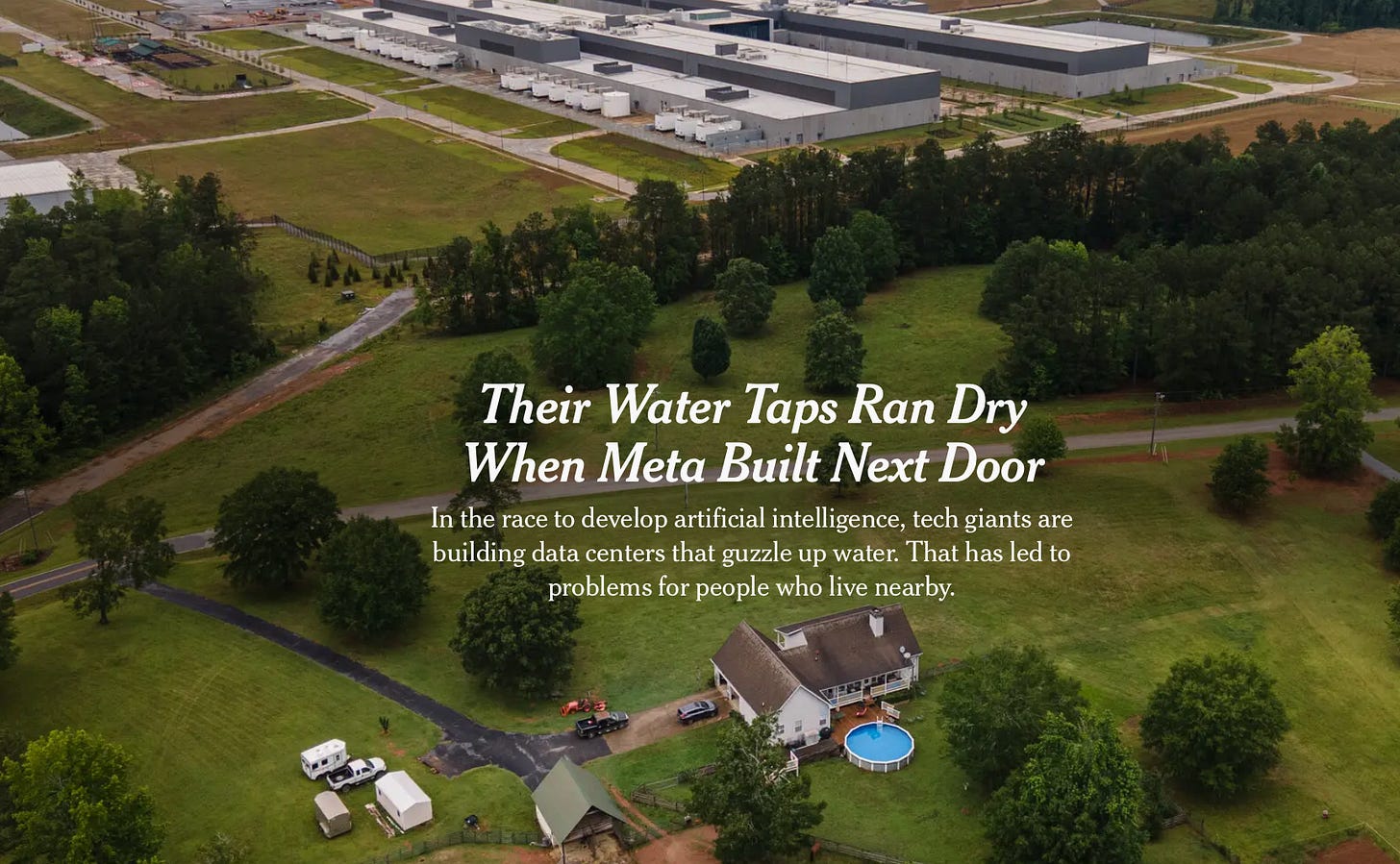

I want to distinguish this from a separate issue, which is not about water use but about water pollution. When I saw this story in the New York Times, I was prepared for it to be about AI water use (“data centers that guzzle up water”), and I wanted to note the irony that the house they depict has a swimming pool.

But a key part of the text is actually about something totally different!

Jeff Morris, 67, eventually traced the issues to the buildup of sediment in the water. He said he suspected the cause was Meta’s construction, which could have added sediment to the groundwater and affected their well. The couple replaced most of their appliances in 2019, and then again in 2021 and 2024. Residue now gathers at the bottom of their backyard pool. The taps in one of their two bathrooms still do not work.

“It feels like we’re fighting an unwinnable battle that we didn’t sign up for,” said Ms. Morris, a retired payroll specialist, adding that she and her husband have spent $5,000 on their water problems and cannot afford the $25,000 to replace the well. “I’m scared to drink our own water.”

This is genuinely really bad. I have no idea if data centers are more likely than other kinds of construction projects to pollute groundwater and destroy neighboring homes’ wells. But clearly, this is the kind of thing that construction projects can do, and while you know I love arguing that we need fewer regulatory impediments to new construction projects, this seems like an extremely legitimate thing to regulate.

Importantly, though, this doesn’t seem to have any relationship to the question of guzzling up water — it seems like a question about construction practices that would apply even if you came up with data centers that didn’t use any water.

It also underscores that while I’m glad people are able to build housing in unincorporated parts of exurban counties (because if not there, where?), it’s actually bad that this has become America’s predominant form of new housing supply. It would be a lot better to have classical urban planning with street grids and municipal water/sewer and the ability to add infill in pace with demand rather than all this well-drilling.

The good news is that on average, American water has been getting a lot cleaner thanks to reduced industrial pollution and better management of runoff. The bad news is that the Trump administration is moving to allow more mercury, arsenic, and benzene into the air and water, while abandoning efforts to decrease PFAS levels in drinking water. They also want to block efforts to reduce the amount of lead allowed in drinking water. The arc of history on these water pollution issues has bent in the right direction over the course of my lifetime, but it remains an important policy problem, and we’re at risk of backsliding. We should distinguish this from questions about water use, though.

Agriculture, especially meat, is the big water user

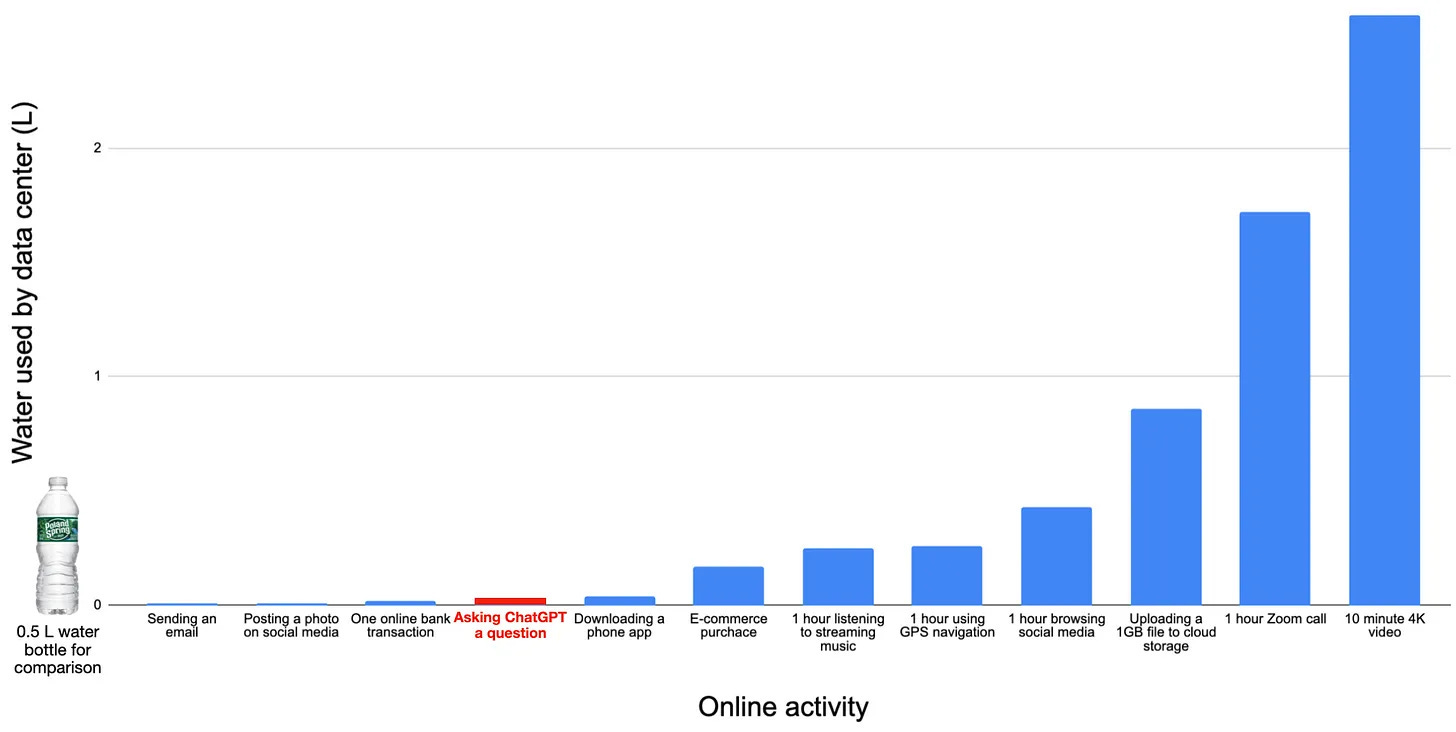

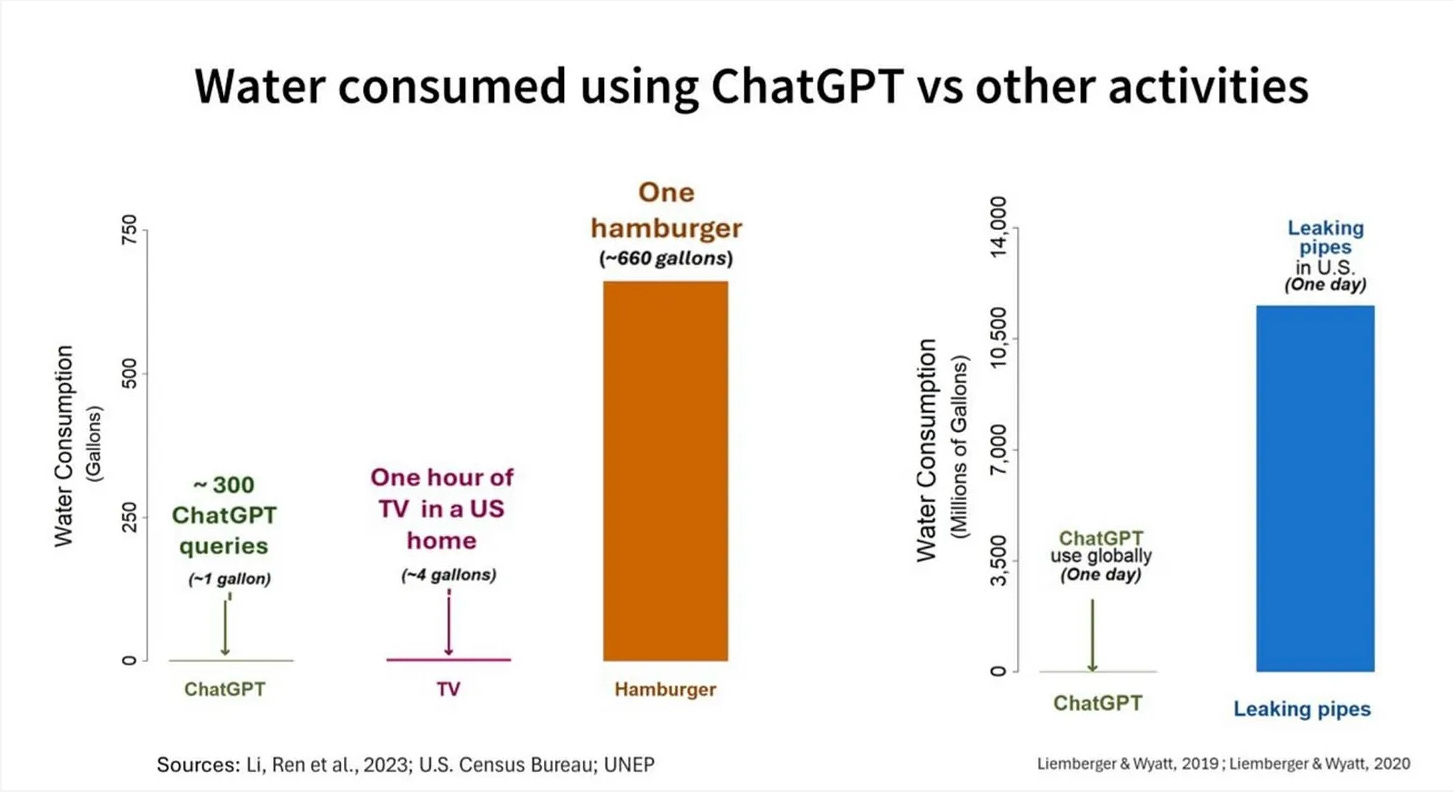

As Andy Masley points out in a great post on the environmental impact of AI, the water use of chatbots sounds like a lot primarily because most people are living their lives in a state of ignorance about the fact that electricity generation and data centers in general use water. If you watch a 4k streaming movie on Netflix, you are burning through many, many ChatGPT queries worth of water.

The true water-guzzler in the American economy, though, isn’t data centers or electricity generation. It’s agriculture, especially the extremely resource-intensive form of agriculture that we use to produce meat.

Historically, meat production took place on marginal lands. Someone would take a hill that was no good for farming and let some sheep graze there, or cows and horses would graze on semi-arid grassland. This is an efficient use of natural resources. People can’t eat grass, but grass grows in places that aren’t good for cultivating staple crops. The flip side, though, is that while letting animals graze on marginal lands is a good use of resources, it doesn’t generate much meat.

Today, only about 5 percent of American beef cattle are grass-fed. Instead of letting animals graze on land that’s not suitable for cultivating crops, we set aside vast tracts of land to grow crops for the purpose of animal feed.

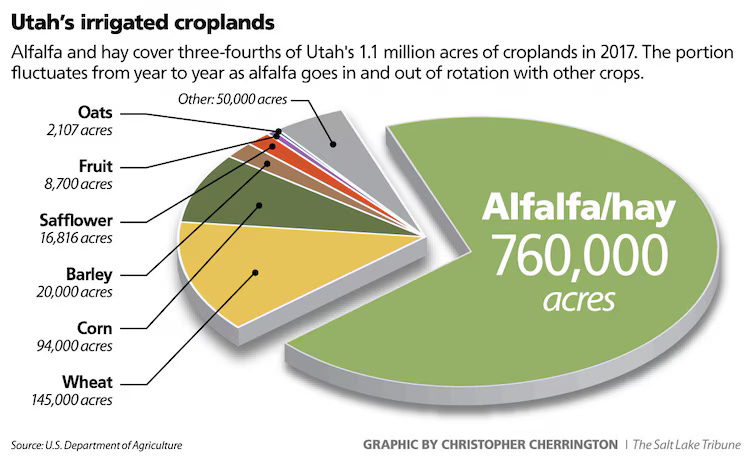

This is all made possible via the magic of rising crop yields, which has allowed the world’s population to grow dramatically even while per capita meat consumption soars. But it does use an awful lot of water. Here’s the Salt Lake Tribune showing what Utah uses its irrigated croplands for, and you can see it’s mostly alfalfa and hay.

The irrigation piece of this is important.

If you’re growing crops, it’s useful to have a lot of sun, but you also need a lot of water. This is sort of paradoxical — the sunniest places are places where it doesn’t rain that much. In premodern times, this meant that the top agricultural regions were in places like Egypt, where a large river flows through the desert. With our feats of modern engineering, though, we’ve been able to bring water to places that are sunny rather than growing crops in the places that are wet.

And this is ultimately what all kinds of western water scarcity issues are about. The United States has a lot of water, but a somewhat limited capacity to transport that water to arid regions.

We also have a long administrative tradition of allocating a disproportionate share of that western water to agricultural rather than residential uses. In the classic movie “Chinatown,” it’s even portrayed as obviously villainous to allocate land and water in suburban Los Angeles to housing rather than farming.

This doesn’t really make sense.

Water is sufficiently plentiful in this country that we can use lots of it for lawns or data centers or alfalfa or golf courses or whatever else we want, while still giving people plenty to drink. But we don’t have unlimited water, so we should aim to level the price across uses so people can make appropriate tradeoffs.

This calculus includes the fact that in the modern day, we can manufacture additional fresh water.

Energy is the real bottleneck for everything

Most of the water on the Earth is in the oceans and is too salty to drink or to use for crops. In principle, salt water can be used for things like data center cooling, but in practice, the corrosive properties of salt mean that companies prefer to pay for fresh water for this purpose as well.

There’s an old-fashioned way of making fresh water out of salt water by essentially boiling it — the water evaporates into desalinated vapor with a salty brine left behind. Capture and cool the vapor, and you have fresh water. This takes a ton of energy and due to the basic physics, thermal desalination methods haven’t improved much over the years. But another method, reverse osmosis, involves pushing water through a semi-permeable membrane that filters out the salt. It’s been getting much more energy efficient (and therefore cheaper) over time.

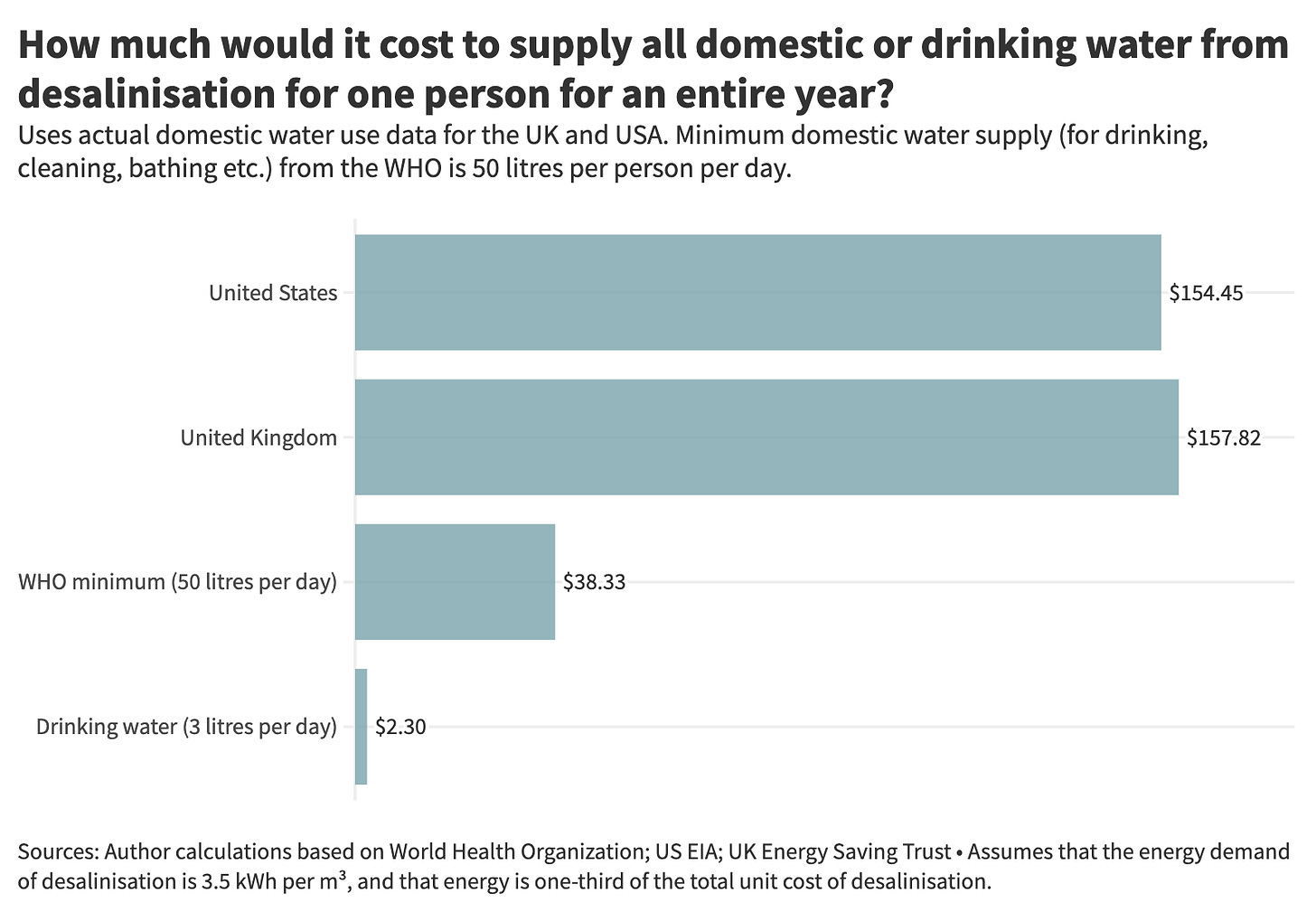

According to Hannah Ritchie’s calculations, we could desalinate the average American’s annual drinking water needs for $154.45, which is just not very much money.

To be clear, that is not all the water that an average American actually uses in a typical year, because (per the whole point of this post) we are consuming lots of water in ways other than drinking. The biggest one here, again, is agriculture. Ritchie ran the numbers on this and says you would need to increase American electricity output by 14 percent to desalinate enough water to meet our current irrigation needs.

That’s not economically viable. But it is worth thinking about.

An acre of solar panels generates a lot more revenue (or embedded energy) than an acre of crops, so instead of diverting rivers to provide water in arid sunny landscapes, we could be “planting” solar panels in the desert and using them to manufacture fresh water via reverse osmosis.

Of course, as always, there are regulatory roadblocks, like the California Coastal Commission blocking desalination plants. More recently, though, the CCC approved a desalination facility, and there’s a brand new one coming to the Florida Keys. Since the United States has relatively abundant fresh water compared to most countries, I would not expect us to be world leaders in desalination. But virtually all environmental issues converge on energy in the long run,1 and in principle, water scarcity can be overcome through more abundant energy.2

To loop this back to data centers, when the Times story moves off the sediment issue and starts talking about actual water use, what they say is that electricity is a much bigger cost for data centers than water. As a result, companies tend to build data centers where electricity is cheap without paying much attention to the water situation. That can put significant upward pressure on water prices.

The article didn’t get into this level of detail, but it’s common sense that local governments should structure their property tax and water billing such that new data centers are net economically beneficial. Zooming out, though, the whole reason data centers are the subject of political controversy is really the energy usage. From the standpoint of hitting emissions targets, it’s inconvenient that we invented a new economically beneficial use of electricity. That being said, it is still better on net to invent useful technologies than to not invent them. The real bottom line is just that inventing and deploying cleaner and more abundant forms of energy is an urgent policy priority, in part for generalized economic growth issues and in part because abundant energy helps solve ecological problems.

Water is an essential resource, and we should push back against Trump’s efforts to allow more pollution and neurotoxins in it. But water scarcity issues can be managed, while the availability of energy is a much more pressing constraint.

Nicholas Muller published a paper recently about the economic history of firewood in the United States, which makes the point that while coal is the dirtiest form of energy that’s widely used today, at the time of its original rise, it was an environmentally friendly alternative to chopping down forests.

We could also dramatically reduce the amount of water needed to grow crops by shifting to vertical farming, but that’s too energy-intensive to be economical today.

I'm an environmental engineer in Southern California and reverse osmosis (RO) systems are one of the things I work on.

It's true as far as it goes that ocean desalination has grown as a water supply option and that energy abundance is beneficial for this. But from the standpoint of water utilities, the relevant question is how ocean desalination compares *to other potential sources* in terms of cost per unit volume of water they can deliver. After all, you generally operate a single interconnected distribution system- so if a new high-volume user (like a data center) forces you to bring online some much more expensive water source, everyone in your service area has to pay for it. And if that means your users are paying for some much more expensive source than the surrounding farmers, they probably won't like that!

Historically, SoCal has been highly dependent on water that has to come a long way through aqueducts from the Colorado River, the State Project, etc. The costs of these imported sources have risen over time, reflecting scarcity of the available flows and conveyance costs, such that a few alternative supplies are now generally economical. As a result, our region *really is* a world leader in potable reuse to replenish surface/groundwater supplies as well as brackish groundwater treatment. Both alternatives include RO and can now be done at costs comparable to imported river water, which is ultimately what drives adoption.

But treating the ocean via RO is still much more expensive because the ocean is orders of magnitude saltier than wastewater or brackish groundwater. So there is a fundamentally higher osmotic pressure and energy intensity as a first-order problem, and the corrosivity of seawater forces you to use expensive materials which also drives up cost. These (more than regulatory concerns) are why utilities right now who are making decisions about alternative sources are going much more in the direction of reuse and brackish groundwater. SoCal has a couple ocean desal facilities, but we probably won't see much more widespread treatment of the ocean unless/until imported water costs get a *lot* higher than they are right now.

"The couple replaced most of their appliances in 2019, and then again in 2021 and 2024. Residue now gathers at the bottom of their backyard pool"

I can't read the whole article so maybe I'm missing something, but If your well is prone to drawing in sediment, the first thing you do is install a $30 whole house sediment filter. If you do this, your water pressure will drop when the filter gets clogged with too much sediment. Then you just swap out the replaceable filter. You can't ruin appliances because sediment can't get past the filter. If they had to replace appliances multiple times, they're likely not getting good advice or there's something else going on beyond sediment.

Also, sediment in well water is natural and I'd say it's the norm, not the exception. My house has a sediment filter that I change twice a year (5 minutes, $10). The filter canister ends up with an inch or two of brown/black sludge at the bottom that I need to rinse out with each change. This is normal. My water tests safe and tastes way better than most any muni water. The addition of the data center might have changed the level of the water table and that could theoretically change the exact composition of the water that nearby wells draw in, but so could a change in water usage by the homeowners.

I think there was a case like this in NH after a spring water company came into a town and built a bunch of extraction wells. The solution was that that company agreed to pay to have some nearby residential wells re-drilled to get them to a depth with decent water flows again.