What the research really says about immigration politics

The literature finds that “accommodating” restrictionists doesn’t work — but you should read it carefully.

Zack Beauchamp recently threw down a gauntlet for those of us who think mainstream center-left political parties need to come to grips with public opinion on immigration.

Beauchamp pointed out that there’s extensive political-science literature on the center-left “accommodation” of populist-right views on immigration and that it largely shows accommodation doesn’t work. He encouraged me and other moderates to take a serious look at it.

But, as I told him, this is the sort of situation that makes me wish for less ideological bias in academic social science.

We all know what the “right” answer on hot-button cultural issues is from the standpoint of basically any faculty meeting in the Western world, so it’s no surprise that, from a pure counting metric, most papers conclude that accommodation doesn’t work. That doesn’t mean the conclusions aren’t true, but it does mean that you have to read skeptically.

Beauchamp told me that he heard what I was saying, but really encouraged me to look into the literature seriously. I respect Zack, and so I did.

My takeaway is that while this literature is fairly convincing, it’s also pretty narrow.

If you pay attention to how exactly “accommodation” is defined and why it tends to fail, I think the findings are consistent with and even supportive of taking a wide range of positions that a reasonable person would characterize as moderating on immigration. But they do knock down a specific kind of moderation that may be overrated in some quarters.

Salience and issue ownership matter

To take one recent research example, a large group of co-authors — Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte, Jack Bailey, Daniel Devine, Zachary Dickson, Sara Hobolt, Will Jennings, Robert Johns, and Katharina Lawall — recently did an event study of Keir Starmer’s “Island of Strangers” speech, which they characterized as “a major rhetorical turn toward anti-immigration positions.” They find that this did not succeed in boosting Labour’s vote share. The abstract says that their “findings highlight the risks of strategic convergence, showing that accommodation of exclusionary rhetoric by social democratic parties is electorally costly for them rather than for their radical right competitors.”

But I think even without trying to poke holes in the research, there’s the question of what they actually found.

To switch issues by way of analogy, Donald Trump benefited electorally from moderating on abortion rights after the backlash to the Dobbs decision. This does not mean that I think he would benefit electorally from doing a series of high-profile political speeches in which he discusses his new more moderate position on abortion rights. It would be a terrible idea for Trump to give an Oval Office address in which he lauds the federalist glory of a woman dying in Georgia due to extensive abortion restrictions while the actual number of abortions performed nationally rises because people can travel to blue states. Trump’s new more moderate position is still unpopular, so driving attention to it doesn’t make sense.

What’s more, he would piss off pro-life figures who’ve been shockingly cooperative with his pivot to the center on the issue. Multiple news cycles would feature Democrats reiterating their popular stance on abortion while Trump articulated his own less popular view and fought with members of his own base. If he did somehow find himself ensnared in that kind of debate, he would almost certainly use his immense agenda-setting powers to say or do something inflammatory on immigration and change the subject back to his strongest issue.

But again, that wouldn’t prove that moving to the center on abortion had failed or that accommodating soft pro-choice views is doomed. Trump has, in fact, pulled off accommodation!

These points about salience are critical.

The Turnbull-Dugarte et al. paper does not offer a hypothesis about why they think Starmer’s speech failed. But a number of anti-accommodation findings specifically point to salience as a key stumbling block.

Christopher J. Williams and Sophia Hunger find that mainstream parties’ efforts to accommodate anti-immigration populist parties’ views lead to “greater public salience of immigration,” which tends to help the populists. In multi-party systems, this often means populist-right parties eat away at the vote share of traditional right-wing parties rather than beat the center-left per se. In last week’s Norwegian election, for example, the governing left-wing coalition secured a narrow re-election victory. But this has definitely not stopped the upward march of the populist-right. Sylvi Listhaug’s Progress Party1 went from fourth place in the previous election to second place in the new election, is now leading the opposition, and, if the incumbent left coalition becomes unpopular, she is well-positioned to win and become prime minister.

Felix Lehmann, similarly, published a paper last year claiming that accommodation strategies don’t work because accommodation “legitimizes” far-right parties and elevates their stature. A paper by Werner Krause, Denis Cohen, and Tarik About-Chadi from 2022 titled “Does Accommodation Work? Mainstream-Party Strategies and the Success of Radical-Right Parties” likewise finds that in the context of multi-party electoral systems, efforts at accommodation “lead to more voters defecting to the radical right” by elevating the salience of their core issue.

Ditching the “accommodation” rhetorical construct, I might summarize the findings as follows: Mainstream parties adopting harsher anti-immigration rhetoric does not reduce the vote share of populist-right parties because it increases the salience of immigration and causes more voters with right-wing views on immigration to vote for the populist right.

What are you trying to achieve?

Note that this account is consistent with my boring theory of the rise of the populist right: that a large minority of people vote for far-right parties because a large minority of the public agrees with them about immigration and crime.

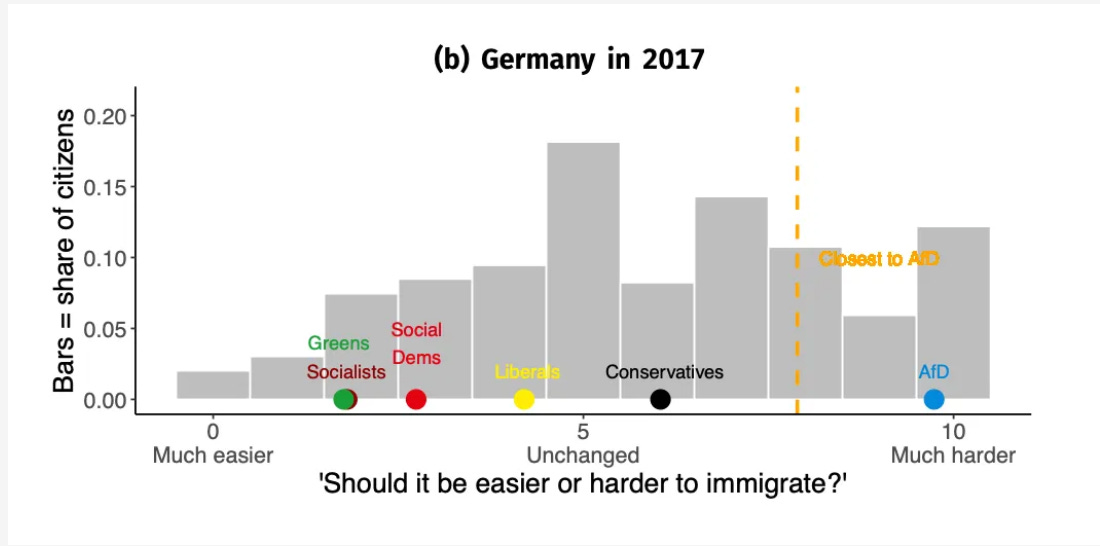

Take a look at this chart from that article showing the ideological position on the immigration question of the German electorate versus M.P.s from German parties.

I look at this and see clearly that if the red-red-green parties want to win more elections, they need to move to the right on immigration, because being way to the left of the median voter isn’t going to work.

This question, about reducing the vote share of Alternative for Germany (AfD), is actually different from the one studied in the accommodation literature. You can imagine a world in which the Social Democrats (SDP) move to the mid-point of the x-axis on immigration and this causes the vote share for both the Conservatives and the Liberals (a center-right party in the German context) to decrease dramatically as some voters embrace the SPD but others break right toward AfD. Whether that “works” depends on what you’re trying to achieve.

In the 2024 United Kingdom general election, Labour’s vote share went up by 1.6 percentage points but they rocketed from 201 seats to 412 seats precisely because the populist right vote soared, which in the context of Britain’s first-past-the-post system meant that Labour did great.

In a happier world, the next part of the story would be, “Once in power, Starmer did a great job and everyone loved him.” Instead, he seems to have floundered and become deeply unpopular, so now the U.K. is on track for a future election in which far-right Reform supersedes the Tories as the main right-wing party and also wins a majority in Parliament. But narrowly speaking, the 2024 election strategy worked great, if you define “working” as “winning the election” and terribly if you define working as “getting people to vote for traditional rather than populist parties.”

Another example: The pro-accommodation side’s favorite case study is Denmark, where the Social Democrats moved to the center on immigration and have been in government for a while.

If you look at the 2022 election, in this case it’s superficially true that the populist-right Danish People’s Party lost eleven seats. But a different anti-immigration party, the New Right, gained two seats. And the Liberal Alliance, a kind of upstart anti-EU party, gained 10 seats.

The really noteworthy consequence, though, was that the Social Democrats’ moves to the center helped induce former Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen to found a new party, the Moderates, with an explicit agenda of forming a grand coalition that would be able to freeze out the far-right without empowering the far-left. This worked, and now the Social Democrats are leading a center-left coalition with Rasmussen’s party and another center-right party. So in this case, accommodation helped radically alter the political landscape, fragmenting the populist-right and incentivizing the center-right to collaborate with the center-left.

I’m a little leery of David Leonhardt’s “Democrats should copy Mette Frederiksen” takes, because he’s comparing two countries with wildly different institutional contexts. But I would say that Fredericksen clearly achieved what she wanted to achieve. Note that mathematically, Frederiksen could have partnered with parties further to her left instead — she just chose not to.

Taking this seriously has pretty moderate implications

The first thing to say about applying any of this to the United States of America is that the multi-party nature of European political systems makes it challenging to know what kind of analogy to draw here.

The Støre Cabinet’s re-election drive in Norway involved a series of moves to the center on immigration. Norway has a highly multi-party political system, but they are also divided into two fairly rigid blocs. The outcome of the most recent election featured both a nice win for the left bloc and a surge in support for the anti-immigration populist party. This is consistent with the “accommodation doesn’t work” literature’s framing of the question. But in America’s two-party context, the traditional right has already been fully subsumed by MAGA, so I don’t know why you’d worry about that dimension of backfiring. You’re trying to win the election, and in Norway that’s what happened.

Similarly, at this point in time, there’s no reason to worry in the United States about “legitimating” anti-immigration politics, because Donald Trump is already president.

More broadly, though, I think it’s important to note that the backfire findings mostly seem to hinge on salience issues.

This is a perfectly reasonable thing to worry about. But I find that progressives in the United States are rarely excited to consistently apply the view that raising the salience of immigration is bad.

I’ve taken a lot of shit over the past several months for having expressed the view that it was a tactical and strategic error to make a big deal out of the Kilmar Abrego Garcia case, precisely on salience grounds. Beyond the specifics of that case, it seems to me that a consistent ethic of “it’s bad to increase the salience of immigration” often calls for a moderate response. Darkly warning that “Trump is building his own paramilitary force” as an interpretation of his huge increase in ICE funding is not an anti-salience play. I think an anti-salience ethic would encourage mayors to be chill and cooperative in response to federal demands, saying something like “our brave officers are busy with a lot of demands on their time but they’re going to do the best they can to help their federal partners out.”

But of course, in the real world, there’s pressure from the base to strike a defiant posture and show that you’re fighting back.

I would mostly ask people to try to be consistent about this. Here are two ideas that I think are broadly plausible:

It’s bad to engage in “tough talk” on immigration or show solidarity with anti-immigration voters’ concerns because that raises the salience of immigration.

It’s really important to “fight back” aggressively and publicly against Trump’s most extreme actions.

But I don’t think that you can hold both of these views simultaneously. If per (2) you are committed to leaning into high-profile fights on immigration policy, then you can’t cite salience per (1) as a reason to avoid tough talk. If you’re going to engage in the fight, then you have to fight with a winning posture, which means acknowledging concerns and being genuinely outraged about immigrant crime and so forth, even while checking abuses.

If you’re going to say “we should be talking about our strong issues rather than immigration” per (1), that makes a lot of sense to me. But then you have to stick to that ethic and try not to take the bait and go chasing every bit of chum that Trump throws in the water.

Governing matters most

Critically, either choice would be more moderate than the casual Bluesky interpretation of this literature, which is something like “political science proved that accommodation doesn’t work, so we need to fight back harder.” What the literature says is that there are complicated tradeoffs around salience, not that maximal defiance is the way to go.

But of course, the most important question is how political actors actually govern.

In recent years, Angela Merkel, Boris Johnson, Justin Trudeau, and Joe Biden all presided in different ways and for different reasons over large increases in immigration levels, and all faced backlash.

I don’t think we should find that surprising or even necessarily an indicator of anything particularly problematic — across all kinds of domains, we see thermostatic backlash to policy change.

But I think it’s clear at this point that increased immigration is politically costly. Johnson may have ended up digging the grave of one of the oldest political parties in the world. Biden, according to Biden, fundamentally imperiled American democracy. Merkel created political space for the AfD to rise, but if she thinks what she did was important on the merits, that’s not necessarily a terrible price to pay.

Trudeau’s Liberals increased immigration levels, but did so in a way that was well-organized. Eventually they ended up changing course on the policy and adopting a new party leader who has continued to pivot toward lower levels of immigration, but it basically worked out fine. In Australia, they have high levels of immigration but the Labor Party has not only continued but in some ways even intensified the harsh treatment of asylum seekers that it inherited from its right-wing predecessors.

It’s a little bit hard to specify the exact parameters through which levels of immigration, change in immigration rates, the skill mix of immigrants, the orderliness of their arrival, and their cultural backgrounds prompt backlash and to what degree. But the specifics of the situation clearly make a difference. The fact that accommodationist rhetoric can backfire in many circumstances doesn’t change the reality that politicians need to accommodate actual public preferences around immigration if they want to win elections.

This party is not what Americans would call progressive.

To lean into the advice in yesterday's column, I think the problem here is that "immigration" as a policy issue encompasses more than one issue and the public has different attitudes about different pieces. Donald Trump has radically restricted asylum and refugee admissions and has gotten ~zero political backlash for it (notwithstanding the dubious legality and clear immorality of the policy). But the mass deportation program has sparked lots of backlash and doesn't seem especially popular. This was the problem with the suggestion that Democrats shouldn't make an issue about the Abrego case--if the question is, should Trump defy the courts to deport someone who's lived here a long time and has US citizen family to a torture prison in El Salvador, that terrain doesn't favor Trump.

It’s good intellectual hygiene to separate which policies you think are good on the merits and which ones are generally popular. I’ve followed Beauchamp for years and there is a consistent inability or unwillingness to make this distinction.

I really do wonder if this is because some people really can’t think through tradeoffs or if this is just an in-group signaling thing.