A boring theory of the populist right

A large minority of the public wants tougher policies on crime and immigration

Almost all theories in elite discourse about why people vote for right-wing populism posit that deindustrialization or free trade or “neoliberalism” or some other thing that left-wing intellectuals think is bad induces support for political parties on the right.

A simpler explanation is that a significant minority of the public in most Western countries agrees with right-wing cultural politics.

I tend to believe that the latter is true.

For example, many rank-and-file G.O.P. primary voters circa 2015 were a bit more moderate than Republican leaders on topics like Social Security and Medicare but more right-wing on immigration and crime. So when Trump offered that set of issue positions during the primaries, his platform resonated with a lot of voters.

This hypothesis tends to be under-explored in the scholarly literature, I think, because researchers are overwhelmingly left-wing themselves. They find the idea that leftward movement on economics could win the hearts of the electorate attractive, and they hate the idea that reverting to 1990s-style Clinton/Blair politics could work well.

A recent paper by Laurenz Guenther of the University of Toulouse breaks with that pattern by taking seriously the idea that populist parties, at least in Europe, are simply responding to voter demand.

In particular, he finds that on most issues, including economic policy and abortion, the distribution of opinions in the mass public and among European members of parliament (M.P.s) are basically the same. Voters disagree with each other and so do parliamentarians, but the overall distribution of opinions is similar if you compare voters and elected officials.

But this is not true of immigration and a couple of other cultural issues. On those questions, incumbent M.P.s are significantly to the left of the population average. Or maybe a better way to think about this is that in most countries, there is a large minority bloc of voters with extreme right-wing views that are echoed by few if any M.P.s, especially from mainstream parties.

In proportional systems, that creates an easy space for new parties to fill. In the U.S., it created space for Donald Trump to remake the G.O.P. I don’t think “the center-left should become more right-wing on crime and immigration” is the only possible conclusion to draw from this data, but I think that everyone ought to take the data seriously and consider the tradeoffs involved in their own choices.

The representation gap

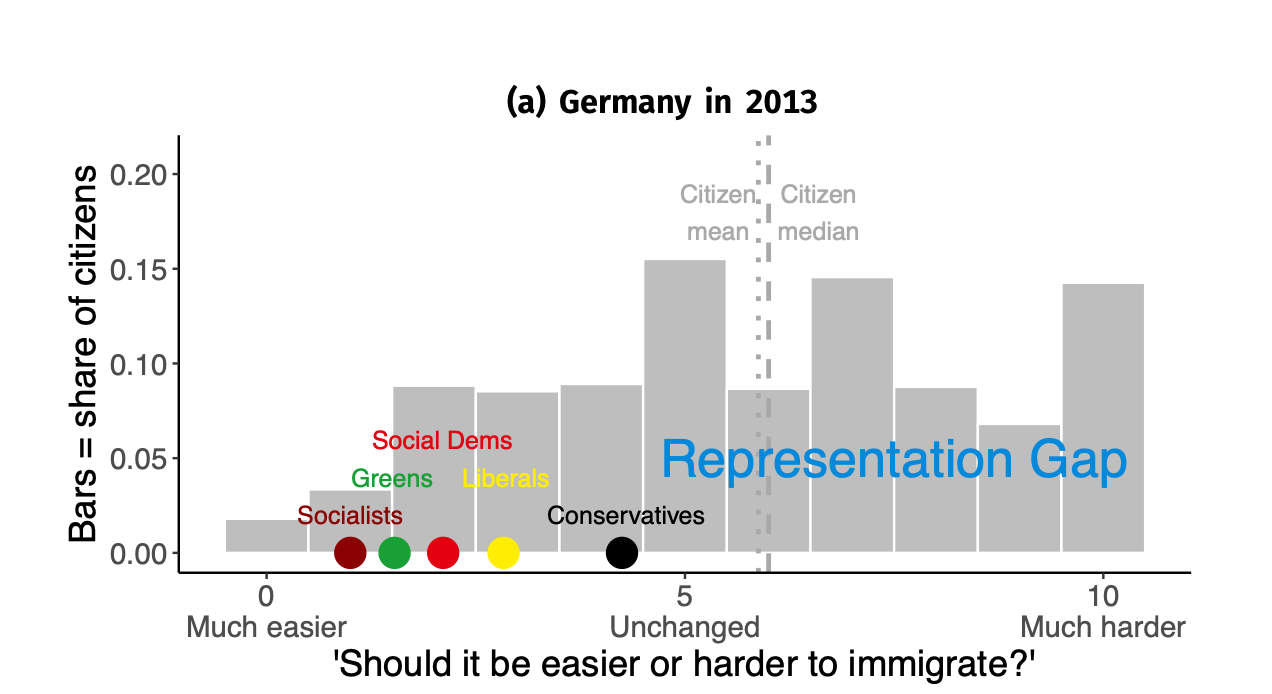

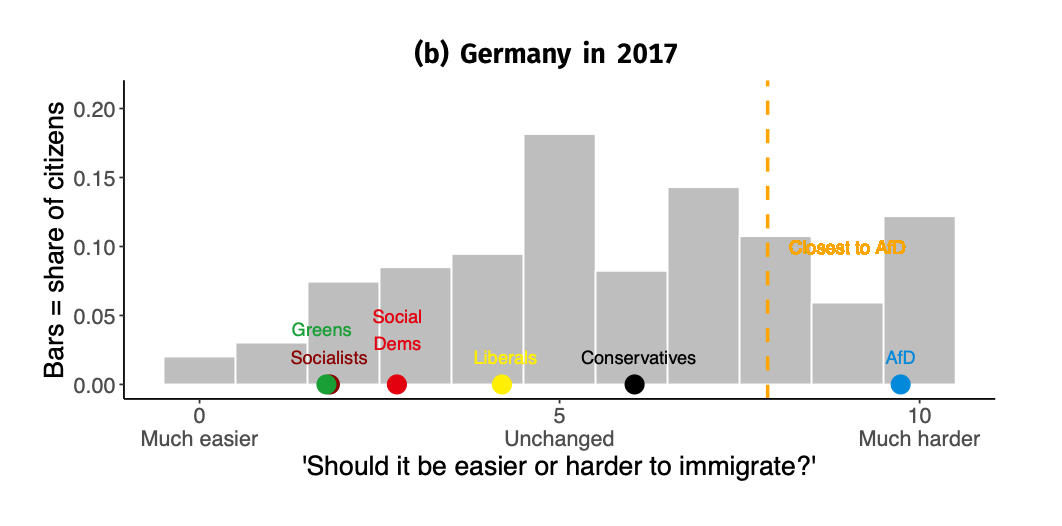

A great illustration of the basic dynamics comes from two charts that Guenther shows about Germany. He’s plotting responses among both citizens and M.P.s to a question about whether it should be easier or harder to immigrate to Germany. Answers are scored zero to 10 on a spectrum of much easier to much harder. The charts show gray bars to illustrate what share of the population takes each position. And then there are colored dots representing the mean responses of elected parliamentarians from various parties.

He shows that in 2013 it’s not just that the left-wing parties were to the left of the mass public on this question, the Christian Democrats (“conservatives”) on his chart were also to the left of the median voter.

Two things follow from this.

One is that it’s challenging for right-wing parties to make much electoral hay out of the immigration issue, because the views of the different parties aren’t that distinct and they themselves are out of step with the public.

The other is that there was clearly an opportunity for a new political party to represent the huge share of the population that wanted more restrictive immigration policy. And that’s exactly what happened as the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party rose to prominence with an extreme position on immigration.

These charts resonate with what I heard from some older people at an AfD rally I attended in Munich during the 2017 federal election campaign. These people said they were longtime supporters of the Christian Social Union, the Bavaria-only sister party of the Christian Democrats. They had backed Edmund Stoiber in the 2002 federal election and didn’t agree with the immigration liberalizations that the Red-Green coalition government that won that election implemented. When the Christian Democrats came back to power under Angela Merkel, they were disappointed she didn’t reverse those changes and were outraged when she went in the opposite direction and opened the door to lots of refugees fleeing Syria. They were annoyed that lots of foreign journalists were characterizing AfD voters as neo-Nazis or something, because in their view they were just voting to uphold the immigration policies of Helmut Kohl and many other mainstream German politicians of the past who nobody thought were Nazis. I raised the point that AfD really does have alarming neo-Nazi ties, and they kind of got annoyed and said their first choice would be for the Christian Democrats to be more restrictionist on immigration, but what are you going to do?

That’s the basic logic of the representation gap. There are a bunch of voters who want right-wing policy on certain issues. If mainstream parties won’t give it to them, they vote for extreme parties.

Representation gaps are large and systematic

Guenther’s point is that this dynamic is not limited to older people in Bavaria. He finds that a representation gap exists in nearly every European country, and that while demographic sub-groups vary in their cultural views the tendency of the public to be more conservative than M.P.s holds across demographics. He finds that “the average citizen, voter, party member, man, woman, educated, uneducated, rich, poor, old, and young person is more culturally conservative than the average M.P. of their country.”

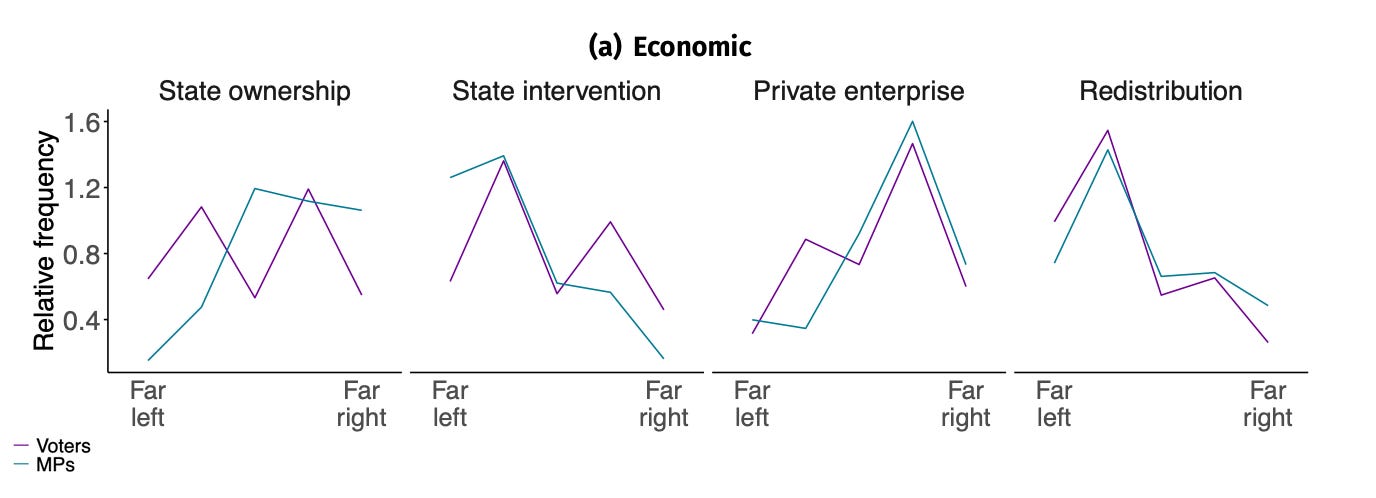

He aggregates survey data across European countries, weighting the value of M.P.s’ responses to the population of the country (i.e., a French M.P. counts for more than a Danish one) and this lets him explore representation gaps across different topics.

On economics, the gaps are very small. The main one is that there is a bloc of far-left voters who say yes to “major public services and industries ought to be in state ownership” but very few M.P.s agree with that. A different question, though, asks if “politics should abstain from intervening in the economy” and on that one there are more far-left M.P.s than voters.

On redistribution, European M.P.s represent their constituents’ preferences well.

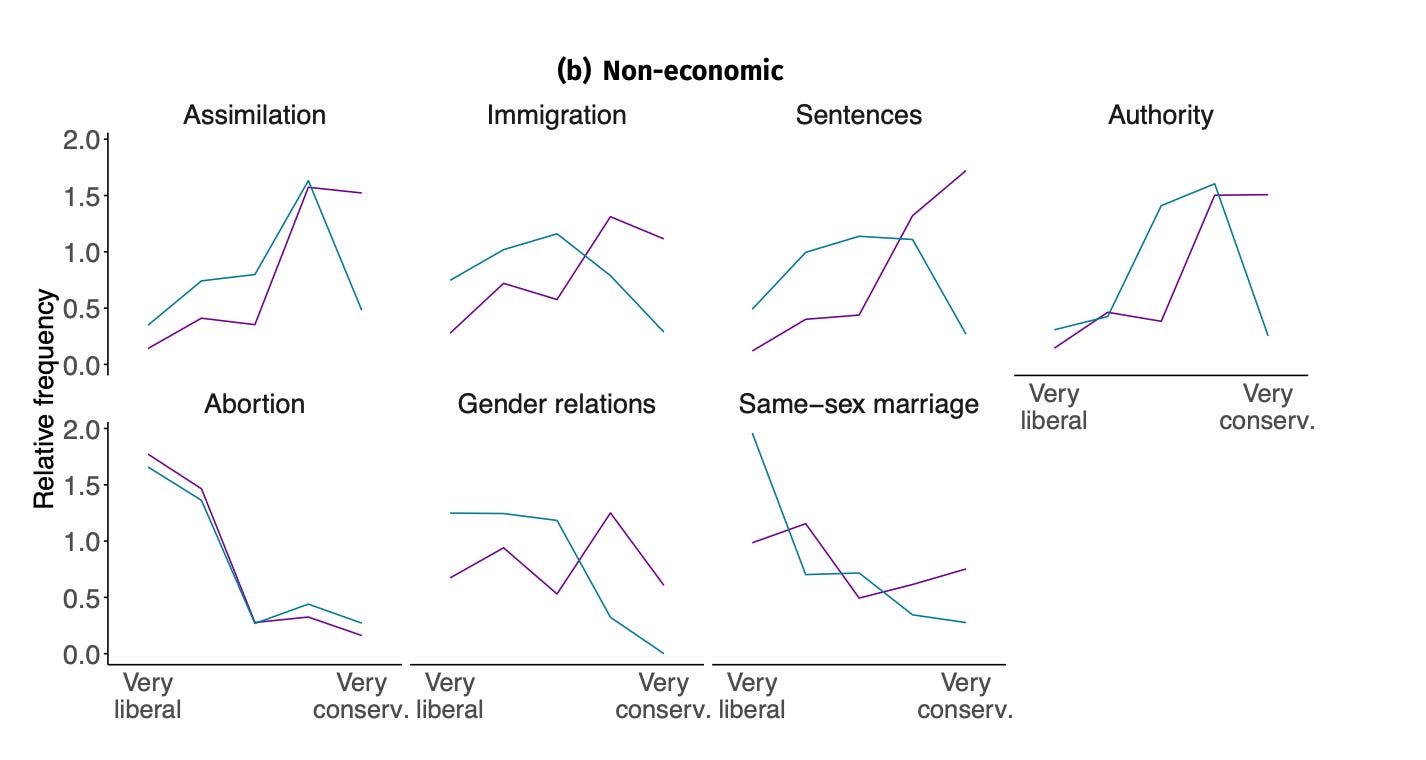

When you turn to cultural issues, the M.P.s are mirroring their constituents’ preferences for abortion rights very well. On immigration, though, there are a bunch of voters who want big decreases and very few M.P.s who agree with them. There’s a related question about assimilation with a broadly similar result.

If anything there is an even bigger gap in terms of voter demand for harsher sentences for convicted criminals. Most M.P.s have moderate views on this, but there are more on the left end of the spectrum than the right. Among the mass public, by contrast, there is a lot of voter demand for harsher sentences.

Part of the reason for the gap is probably that M.P.s have to think more concretely about tradeoffs. It’s a lot easier to tell a pollster you want harsher sentences or tweet about how we could end crime by locking up repeat offenders and throwing away the key than it is to specifically write down what taxes you want to raise or what spending you want to cut in order to accomplish that. But some of the gap is simply a disagreement about values. You see that especially on the gender relations question, which is phrased to be basically pure vibes and not something you could write down as a piece of legislation: “a woman should be prepared to cut down on her paid work for the sake of her family.” The voters are all over the map on this one, but almost nobody in parliament has the very conservative view. Similarly, a non-trivial minority of the public says yes to “schools must teach children to obey authority,” which is very unpopular with M.P.s.

The populist conundrum

One notable aspect of Western right-populist politics is that a lot of its leading proponents are colorful outsider figures with a total lack of respect for conflict-of-interest rules or conventional standards of propriety. That’s the trail that Silvio Berlusconi blazed and that Donald Trump walked down. A lot of populist groups have troubling connections to actual Nazi movements. Many of them appear to be either dupes or willing agents of Russian foreign policy.

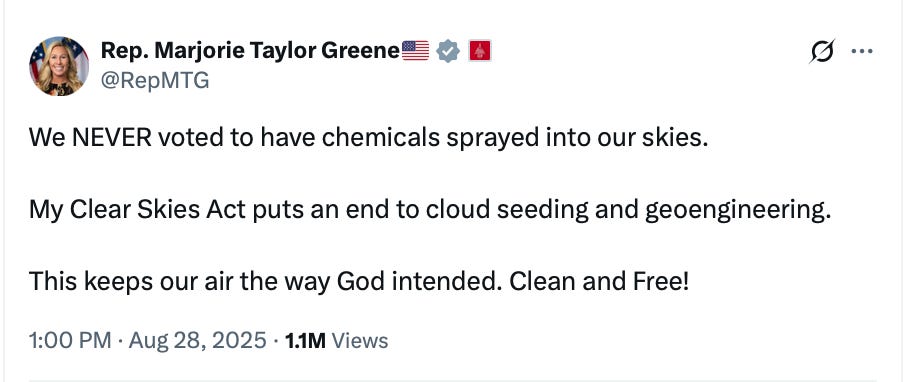

Populist movements are also associated with, well, populism — a general disrespect for established institutions and hierarchies of knowledge and authority. Populists are interested in weird conspiracy theories about cloud seeding and geoengineering.

A certain share of the public are cranks. They talk a lot about “chemicals” and instead of just saying it’s good to eat healthy food and get plenty of exercise, they link basic personal health advice to strange ideas about mitochondria. In the United States, these kind of crank notions used to be evenly distributed across the political spectrum — R.F.K. Jr. was a prominent (albeit slightly embarrassing) Democrat in good standing. Now, populist movements have realigned crankery and are associated with odd ideas about vaccines and blowing off normal economics wisdom about things like tariffs and central bank independence.

Many of these movements appear to be hostile to the basic principles of constitutional liberalism and electoral democracy, and many of us find these aspects of populism to be particularly troubling.

I do not personally favor longer prison sentences, reducing the volume of immigration, or scolding mothers for working too much. At the same time, were a government to come into office that cut immigration, increased prison sentences, and said vaguely encouraging things about tradwives, it wouldn’t be the end of the world. In politics, sometimes you win the argument and sometimes you lose. But if deeply illiberal people come to power and trash the basic institutions of Western democracies, that’s not just something we come back from.

My sense that Trump is doing irreparable damage to the United States does not really stem from his views on crime and immigration. It’s based on his total disrespect for constitutional government, the rule of law, ethics, science, economics, and basic human decency. The problem is that while these right-wing views about immigration, crime, and gender roles are not per se illiberal, you can see why they disproportionately appeal to people with illiberal views and authoritarian mindsets. If all the elites who favor democratic institutions also refuse to supply the policy options on immigration and crime that the voters want, then voters will ultimately get those policies from more sinister types.

Politics as a vocation

One reason for this representation gap is that so many people who are left of center now view cultural questions as beyond the legitimate scope of political bargaining or pandering.

Everyone needs to think harder about this.

The ‘90s were a long time ago, but they’re not ancient history. Bill Clinton ran on increasing the length of prison sentences and expanding the use of the death penalty. Not only did that allow him to balance the budget while making the tax code more progressive, he also set important milestones for progressive cultural politics. He had what was at the time the most diverse administration on record by a large margin. He safeguarded abortion rights. He promoted women to high office in unprecedented ways. As recently as 2008, Barack Obama took a dive on same-sex marriage equality, and people with progressive views on the issue generally approved of him doing so.

I think the decline in this spirit of pragmatism is an underrated driver of the unraveling of democratic stability over the past 10-15 years.

If decent people decide to shun everyone who fails to embrace certain progressive cultural values, then we end up with a bunch of very indecent people winning elections and everyone standing around wondering what happened. Trying to get around this dynamic by ratcheting up the level of economic populism without addressing the cultural issues on their own terms is unlikely to work. If you’re comfortable with Trump/Berlusconi/AfD types winning elections and wielding power, maybe that’s fine. But I take all these warnings about authoritarianism seriously.

The only way to beat authoritarianism, though, is with actual democratic politics. And I think that requires elected officials who take the vocation of politics seriously enough to represent the authentic values of the electorate, rather than ceding all power to people who disdain democracy.

"If liberals insist that only fascists will enforce borders, then voters will hire fascists to do the job liberals refuse to do."

https://archive.ph/PXfd2

This is a key point: "Part of the reason for the gap is probably that M.P.s have to think more concretely about tradeoffs. It’s a lot easier to tell a pollster you want harsher sentences or tweet about how we could end crime by locking up repeat offenders and throwing away the key than it is to specifically write down what taxes you want to raise or what spending you want to cut in order to accomplish that."

Apply this to immigration, too. You want less... but are you willing to pay the cost?

If the median voter wants to make it harder to emigrate to Germany, the United States, and most everywhere else. But what about the tradeoffs incurred? Does the average voter also want more expensive healthcare and longer wait times? How about food-price inflation? Maybe they'd be less happy if their local elementary school closed? Remember when everyone was freaking out that "nobody wants to work anymore?" Y'all ain't seen nothin yet!

These effects and immigration only seem unrelated because people still aren't contending with the fact that the *only* reason that populations haven't been in free-fall across the Western world for years now is immigration. And that everything they consider "normal" is extremely sensitive to the working-age population and labor supply. Places like Japan have been foreshadowing our future my while life, but they actually adapted to their new reality in ways that I don't think the American system (or psyche) is really prepared for.

But maybe we'll all learn fast because the US population has just shrank for the first time in its history. Note that the American population didn't shrink during the Civil War, either of the World Wars, or the Great Influenza. But now it has. For. The. First. Time. Ever. And almost entirely due to the MAGA immigration policy (plus decades of below-replacement birthrates).

It takes people a while to notice the knock-on effects of something so catastrophic, but they will. You say it "wouldn't be the end of the world." But people were OUTRAGED that they couldn't get their McDonald's or Starbucks in a timely fashion during COVID. And, already, Trump got a little wobbly with the obvious acute effect of his immigration raids on the food production sector and reversed. And anti-immigration is his whole thing! How quickly will the MAGA diehards among the votership suddenly notice the upsides of having a bunch of erstwhile undesirable Haitians and Venezuelans around? I'd wager sometime before 2028 at this rate...

People in Germany and Italy don't have to wait so long. The shrinkage is happening now. And so are its deleterious effects. But they still want less immigration. So who's going to tell everyone that you can't have your cake and eat it too? Maybe I'm wrong and motivated reasoning and propaganda inure everyone from the truth that not having babies and not having immigrants is when we can't have nice things, anymore. But we're recovered from spats of xenophobic populism before when everyone feels the concrete effect of fewer people.