What anti-Covid policies actually work?

What we've learned from two years of research

This piece is written by Milan the Intern, not the usual Matt-post.

As we approach two full years of Covid-19, I wanted to take a look back at what two years of research can tell us about which policies worked and what we ought to do going forward. Hopefully, readers will find this helpful.

Vaccines are the most effective tool we have against Covid

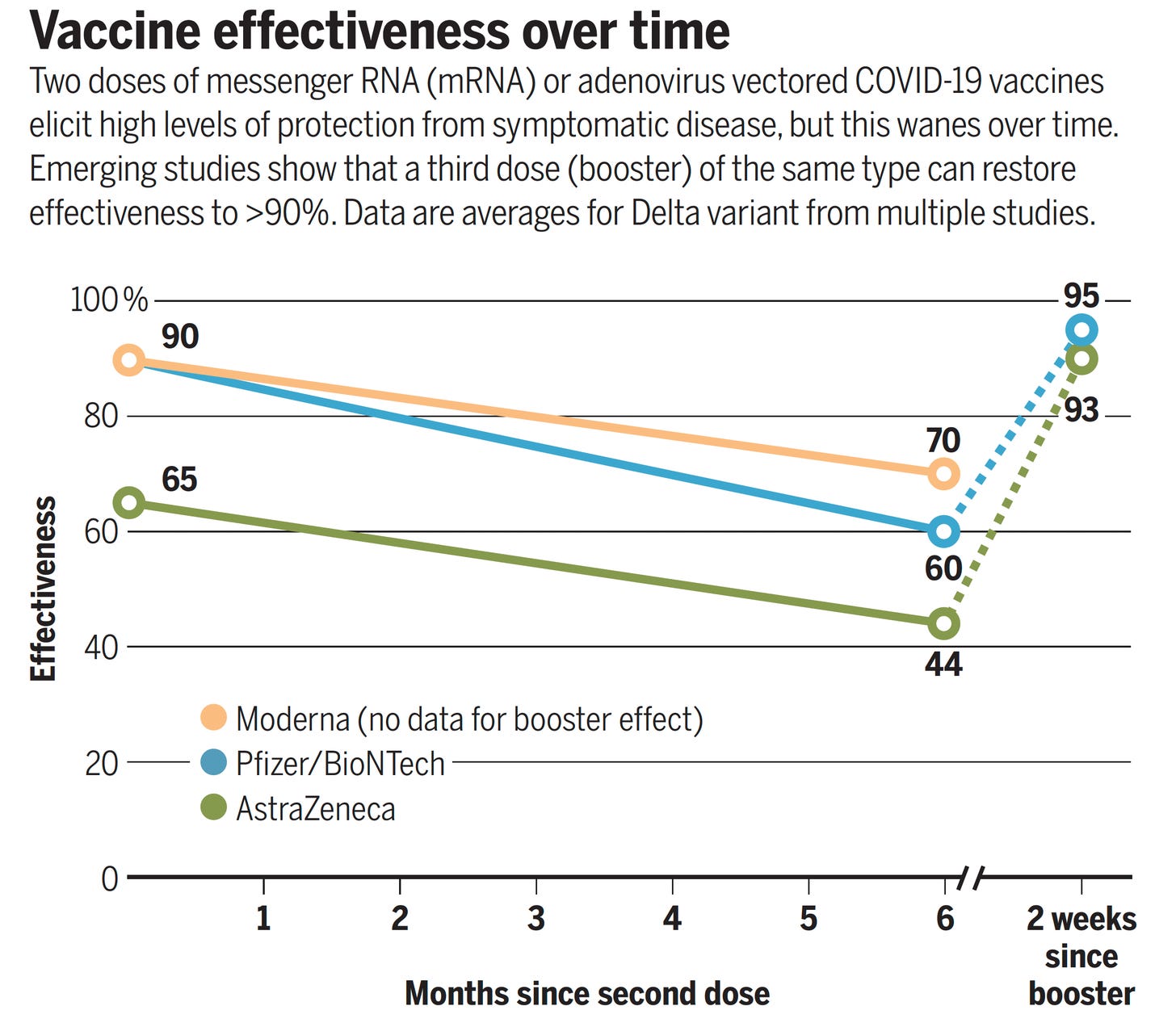

The good news is that vaccines work. Before Delta and Omicron, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were around 95 percent effective at preventing illness from Covid-19, while the Johnson & Johnson shot was 72 percent effective at preventing infection and 84 percent effective at preventing severe disease, according to the FDA’s analysis.

The protection given by vaccines seems to wane over time, which is why the CDC now recommends booster shots, which are especially important for those whose first dose was Johnson & Johnson.

Due to Omicron’s higher transmissibility, most vaccines will no longer offer complete protection against infection (I am walking proof). But they still offer significant protection against severe illness, hospitalization, and death. One study from the Yale School of Public Health found that vaccines saved 279,000 lives and prevented 1.25 million hospitalizations before the Delta wave in America, and a recent CDC analysis found that boosters are 90 percent effective at preventing hospitalization from Omicron.

The long-term goal is to develop a pan-coronavirus “supervaccine” that would protect against all viruses in the coronavirus family (including all variants). Researchers at Walter Reed have created a prototype of such a vaccine that needs to go through phase 2 and 3 human trials, so keep your eyes on that. In the meantime, Israel has begun offering fourth shots to those especially at risk, such as the elderly and immunocompromised.

TL;DR: Vaccines reduce — though do not eliminate — your odds of catching Covid-19 and drastically reduce your odds of getting seriously ill or dying. If you haven’t already gotten your shots, you should do so ASAP and urge family and friends to do the same.

Overcoming vaccine hesitancy

If you are reading this newsletter, you are probably already vaccinated. Unfortunately, there are a lot of people who aren’t (the “vaccine-hesitant,” as the experts call them) and that’s a problem.

It makes it harder for us to reach herd immunity — to the extent that that is still possible post-Omicron — which increases the chances that new, more infectious, and/or deadlier variants evolve. But it also means a lot of preventable death and suffering.

So far, policymakers have tried a few methods to increase vaccine uptake in a non-coercive fashion.

The first is public health messaging. In March, former presidents Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama filmed a 60-second advertisement urging Americans to take the vaccines. Celebrities such as Olivia Rodrigo, Dolly Parton, and Magic Johnson have also publicly promoted vaccination. In April, a group of GOP lawmakers with medical backgrounds filmed a two-minute spot urging conservatives to get vaccinated in order to end pandemic restrictions. And of course, the CDC and other public health agencies have promoted getting the shots.

The issue is that views on vaccines, in general, had been polarizing on partisan lines before the pandemic, and many conservative media outlets and prominent GOP politicians have been promoting misinformation about Covid-19 vaccines specifically. The result is that a large share of Republicans say they won’t get vaccinated, borne out in data showing a partisan gap in views on Covid-19, vaccinations, and deaths.

Second, there are vaccine incentives such as cash. Washington, D.C. offers $51 for bringing a friend or family member to get vaccinated, while New York City offered $100 for people to get their first shot (the latter program has since ended). Washington state got creative and offered “Joints for Jabs” at participating dispensaries.

Finally, following the lead of Ohio, states rolled out vaccine lotteries, where getting your shots entered you into a drawing to win prizes such as $1 million for adults or free tuition at a state university for those under 18. Barber and West (2021) found that Ohio’s lottery increased the share of the state that was vaccinated by 1.5 percentage points and averted $66 million in healthcare costs for the price of $5.6 million. But other studies that controlled for the effect of the CDC greenlighting vaccines for kids 12-17 around the same time — such as Walker et. al (2021) — have shown conflicting results.

TL;DR: In general, evidence has been mixed for vaccine lotteries, and even if the effects are positive they are likely small. Likewise for other non-coercive measures such as cash incentives and public health messaging.

Vaccine mandates work

The other option for increasing uptake is a coercive approach: vaccine mandates. In September, President Biden attempted to institute a national vaccine mandate covering firms with 100 or more employees through OSHA. France has instituted a digital Covid-19 passport, requiring proof of vaccination to enter bars, restaurants, movie theaters, and trains. It now has one of the highest vaccination rates in Europe, after being considered one of the most vaccine-skeptical nations. Austria and Germany seem poised to follow suit, with Austria planning to fine those who have not been vaccinated by March a minimum of €600.

Many colleges in America have also required vaccines for students and faculty. Consider the vaccination rates for undergraduates at colleges with mandates compared to the vaccination rates in the counties where those schools are located: Ohio State is at 91.3 percent (compared to 72 percent for Franklin County), the University of Maryland is at 98.2 percent (compared to 80 percent for Prince George’s County), and Yale is at 99.6 percent (compared to 84 percent for New Haven County).1

TL;DR: When enforced, mandates work. However, they may run into legal trouble. Over the summer, the Supreme Court declined to block Indiana University’s vaccine mandate and has refused to overturn several state and local mandates, but it recently voted 6-3 to overturn Biden’s national vaccine mandate.

Masking reduces spread, especially indoors

Before we had vaccines, masking was one of our most effective tools for controlling the virus. A meta-analysis by Talic et al. (2021) found that mask-wearing led to a 53 percent reduction in new Covid cases.

N95 or KN95 masks are the most effective option, followed by surgical masks and then cloth masks. Ueki et al (2020) find that cloth masks reduce the wearer’s intake of virus particles by 17-27 percent, surgical masks reduce intake by 47-50 percent, while tightly-fitting N95 reduced it by 79-90 percent. Layering a cloth mask on top of a surgical mask can improve protection if N95s aren’t an option, but there are some caveats. Outdoor masking seems to be mostly unnecessary, especially if you’re vaccinated.

The Wall Street Journal put together a nice graphic on how long it takes to spread Covid with different masking scenarios using data from the spring of 2021.

Omicron likely reduces the efficacy of masks, and the widespread availability of vaccines also weakens the case for masking because the shots drastically reduce the risk of serious illness and death.

TL;DR: When indoors, N95/KN95 > double masking > surgical > cloth > nothing. Outdoor masking is mostly unnecessary.

Mask mandates can work if they are enforced

A related question is whether mask mandates work.

It’s hard to get precise data for this kind of question. A study by Jehn et. al (2021) looked at data from public schools in Arizona and was cited by the CDC in defense of school mask mandates. It was criticized by David Zweig of The Atlantic for methodological and data errors, including using case data from a time period when most Arizona schools were closed. A different CDC study by Budzyn et. al (2021) found that counties with school mask mandates saw 18.53 fewer cases per 100,000 children and adolescents, but did not control for factors such as county-level teacher vaccination rate and school testing policies.

Guerra & Guerra (2021) looked at state-level mask mandates and “did not observe [an] association between mask mandates or use and reduced COVID-19 spread in US states.” A 2020 analysis from Goldman Sachs estimated that a national mask mandate could increase the share of people wearing masks by 15 percentage points, cutting the daily growth rate of cases by 0.6 to 1 percentage point and substituting for lockdowns that would cost 5 percent of GDP.

Lynne Peeples in Nature magazine looked at the literature on mask mandates, writing:

In a similar study in the United States, published this January5, researchers found that a national mandate for employees to wear face masks early in the pandemic could have reduced the weekly growth rate of cases and deaths by more than 10 percentage points in late April 2020. The study suggests that this could have reduced deaths by as much as 47% (or by nearly 50,000) across the country by the end of May last year. Another preprint, published in October, linked mask mandates with a 20–22% weekly reduction in COVID-19 cases in Canada6.

Still, US data suggest that regulation alone might not have been enough to produce a benefit from masks. In a survey of more than 350,000 people, published this March, self-reported mask wearing increased separately from government mask mandates7. The mandates do have an effect, “but when we looked at it, it was really the behaviour of the population that was a better metric”, says John Brownstein, an epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and a co-author of the study. “There’s a difference between government policy and community buy-in.”

The biggest factor seems to be how strict adherence is in practice. As Peeples notes, South Korea has a much more pro-mask culture than the United States, leading to widespread adoption of masks during Covid-19. When I was in Paris over the summer, someone on the train reminded me to pull up my mask; at the CVS in Porter Square, nobody really bats an eye if your mask isn’t covering your nose. Gavin Newsom isn’t sending state troopers out to fine or arrest people violating California’s mask mandate. And of course, plenty of red states don’t have mandates and have governors that are explicitly anti-mask.

TL;DR: Mandates can reduce spread, but only if they are followed and enforced.

Six feet or three?

Covid-19 primarily spreads through aerosol droplets and the further away one gets from the source of the aerosols, the lower the concentration of viral particles. Your risk of infection increases with the amount of virus you’re exposed to, so the idea behind social distancing is to space people out such that the risk of transmission is reduced. And it so happens that respiratory aerosol droplets don’t spread beyond six feet, hence the “stay six feet apart” guideline.

A lot of the studies on social distancing use mobility data, usually from people’s smartphones. Basically, the researchers are tracking how much people go out of the house and then seeing if people who go out less are less likely to get Covid-19 (they usually are). But this isn’t what we’re looking for — we want to see if making people stay six feet apart reduces the spread of Covid-19 in a given jurisdiction.

Fazio et al. (2021) did a creative survey of individuals’ social distancing behavior — not relying on mobility data — and found, “The more participants practiced social distancing, the less likely they were to have contracted COVID-19 over the next 4 mo. In fact, an increase of one SD on the virtual behavior measure of social distancing was associated with roughly a 20 percent reduction in the odds of contracting COVID-19.” A study by Van den Berg et al. (2021) looked at public schools in Massachusetts with different distancing requirements (three feet minimum vs. six feet minimum) and found that case rates among students and staff were similar in both categories, strengthening the case for lower distancing requirements in schools.

TL;DR: Six feet of distancing does seem to reduce cases, but in schools, three feet seems to work just as well. But distancing is more than three times less effective at preventing infection than vaccination, and once again adherence is everything.

School closures are bad

The bigger controversy about schools is over remote learning. Matt has already written two articles on school closures (here and here). From the most recent one:

McKinsey and NWEA found huge learning losses concentrated in poorer kids nationwide. Texas and Indiana reported big early test score declines. A study from the Netherlands indicated that during an eight-week period of virtual schooling, students learned basically nothing on average.

Halloran et al. (2021) found that “pass rates [on standardized tests] declined compared to prior years and that these declines were larger in districts with less in-person instruction. Passing rates in math declined by 14.2 percentage points on average; we estimate this decline was 10.1 percentage points smaller for districts fully in-person.” These changes were smaller for English scores but larger in districts with more Black, Hispanic, and free lunch-eligible students.

David Leonhardt of The New York Times also has a good rundown of the research on online schooling, concluding that “remote schooling, in other words, may be more akin to dropping out than it is to attending in-person school.” Elsewhere, Leonhardt has noted that Covid-19 poses very little risk to children — as he wrote in October, “an unvaccinated child is at less risk of serious Covid illness than a vaccinated 70-year-old.” But Zoom school has taken a serious toll on the mental health of students, and according to the CDC, “multiple studies have shown that transmission within school settings is typically lower than – or at least similar to – levels of community transmission when prevention strategies are in place in schools.”

Of course, there is still some risk, but we have a pretty good prevention strategy in our hands: vaccines!

TL;DR: The evidence is quite clear that remote schooling hurts children by significantly stunting their learning, especially for students already at a disadvantage, while the risk of Covid-19 to kids is quite low even without vaccination. Additionally, remote learning has a serious, negative impact on student mental health.

“Covid Zero” no longer makes sense

There are several countries, mostly in Asia, that have pursued a “Covid Zero” policy — that is to say, trying to eradicate the virus entirely. And for a while, they were pretty successful at it.

So what was their secret?

Part of the equation is travel restrictions. As Matt detailed in “The road not traveled,” travel restrictions can be very effective, if they’re strictly enforced (are you sensing a theme here?). The restrictions the U.S. put in place had all kinds of loopholes. Even blue state, Covid-hawk governors weren’t sending state troopers to make sure that out-of-state-visitors were complying with quarantine rules. In New Zealand, most people were blocked from entering the country and those who did come in had to stay at a special quarantine facility for 14 days. South Korea was able to get Covid-19 under control by doing a lot of testing and contact tracing, but they also had very strict quarantine rules if you tested positive and mask mandates that were rigorously enforced.

Consequently, many Asian nations have very low Covid-related death tolls.

But the situation has fundamentally changed —the new variants are just so infectious that even these strict quarantine and travel ban policies aren’t containing the spread anymore, and one can’t keep a country in lockdown ad infinitum.

New Zealand officially ended its Covid-zero policy in October, with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern saying “With Delta, the return to zero is incredibly difficult, and our restrictions alone are not enough to achieve that quickly. In fact, for this outbreak, it’s clear that long periods of heavy restrictions have not got us to zero cases.” Australia has also rolled back its Covid-zero regime, allowing cases to rise so long as hospitals had the capacity to deal with them. China is officially still pursuing Covid Zero through extremely strict policies, but it looks like an increasingly futile cause.

Across the pond in Britain, they famously mail free antigen tests to everyone’s homes but they haven’t escaped the surge in cases from Omicron, and the government is now considering winding down the program because it’s very expensive.

TL;DR: Covid Zero and strict test-and-trace policies were effective for a time — they kept per capita cases and deaths much lower in countries such as South Korea and New Zealand. But Omicron spreads too quickly for Covid Zero to work, and vaccines mean that cases are increasingly mild.

Where do we go from here?

One broad theme we can draw from this exercise is that everything is about adherence — you could have the best policies in the world but it won’t do you any good if nobody is following the rules.

If you look at American public opinion, voters are strongly opposed to remote learning and a global lockdown and are in favor of social distancing and masking. But masking and distancing are hard to enforce and both are less effective at reducing serious illness and death than vaccines and boosters, which voters oppose mandating. So it’s a tough situation.

So far I have tried to keep this post free of my personal opinions and focused on summarizing the research for readers, but I’d like to close with a brief take.

My read of the evidence is that our primary tool going forward really ought to be vaccines. We should continue working towards a supervaccine and new treatments, and we should ensure developing countries have access to these medicines. Congress ought to spend more on pandemic prevention.

A significant minority, mostly on the political right, has decided that they don’t want to get vaccinated. I think they’re making a mistake, I sincerely hope that they change their minds, and we should try to convince them to come around. But at the end of the day, if they’re choosing to take a risk with their health, that’s their decision. The juice just isn’t worth the squeeze when it comes to NPIs that are weakly enforced, that unvaccinated folks probably won’t follow anyway, and that extract a significant toll on society.

More importantly, we all need to accept the fact that Covid-19 isn’t going anywhere, and that a somewhat heightened risk of respiratory illness is going to be the new normal. It’s time to adapt to that new reality.2

Take the figures for vaccination rate by county with a grain of salt — they’re from The New York Times Covid dashboard, which is based on potentially faulty CDC data, as covered in “The CDC's vaccine data is all wrong.” Regardless, I am quite confident that the colleges’ vaccination rates are significantly higher than the surrounding counties’ rates.

An example of adaptation would be ditching useless measures such as surface disinfection.

I don't understand why we continue with anything other than vaccination at this point outside of particularly sensitive places (hospitals, nursing homes, etc.). Masks and social distancing make sense when there is nothing else but we're way passed that. I can't be the only person that thinks its farcical to walk into a restaurant masked, remove it at the table for an hour while talking and eating, then put it back on to leave. I mean, does the virus call a truce while we sip our beers? Was it fooled by wearing a mask at the hostess stand?

If we were a more mature people socially and politically we would drop the silly theater, mitigate as best we can with our (really quite amazing) vaccine technology, and then go about our lives.

What about ventilation? We should be improving ventilation in public spaces to prevent asthma alone, but I think it could also be good for preventing COVID spread in some cases.