We’re sleeping on the most dangerous situation in the world

India, Pakistan, and the shifting balance of power

On the list of things that are under-discussed in the United States relative to their objective importance, the relationship between India and Pakistan is a perennial favorite.

Here we have the world’s number one country by population squaring off against the number five country by population. They’ve fought multiple wars over the past few generations. They both have nuclear arsenals. And while the actual point at issue in the conflict is normally kept nicely under wraps, there’s been basically no progress in my life time — or really ever — on addressing the underlying political dispute over Kashmir. As a result, one of the big known unknowns about the world is always that something bad might happen in the region and it could escalate and spiral out of control.

And this spring, it happened.

Armed Islamists massacred Hindu civilians in India-controlled Kashmir. The Indian government blamed the attack on Lashkar-e-Taiba, a Salafi group based in Pakistan that has operated across borders in Afghanistan and India in the past and that has a kind of ambiguous relationship with Pakistani intelligence services. The Indian government struck back with Operation Sindoor, striking targets in both Pakistan-controlled Kashmir and Pakistan itself. Pakistan says they shot down several Indian planes, and even as diplomats have been scrambling to find off-ramps and a path to de-escalation, there’s been cross-border artillery shelling and military drones flying across the border.

A ceasefire was brokered over the weekend, thankfully, which seems to be basically holding, despite some claims of violations.

But on the list of things that could possibly escalate into a giant war resulting in death on a massive scale, this definitely seems like the most probable one at the moment. And yet it secures relatively little attention in the United States. The (perennially underrated) mainstream media is, I think, actually doing a good job of offering earnest multi-faceted coverage of the issue. But as far as I can tell, none of that coverage is attracting much readership compared to tariff news or write-ups of Trump’s various bizarre statements. So there just isn’t very much coverage and certainly not a lot of social media buzz in the US.

The reasons for that aren’t that hard to discern. This conflict doesn’t seem to have much to do with the American government, and most Americans don’t have strong feelings about the substance of it. When Trump vaguely mused that this dispute “has been going on for 1,500 years, probably longer than that,” informed Americans understood that this was bad chronology. But I think for most Americans, the (basically true) idea that Muslims and Hindus have been at odds in South Asia on-and-off for a long time is roughly their desired level of engagement with the situation.

Yet I think this is part of the problem: While Americans and the American government don’t particularly care about Kashmir, we do care more broadly about the politics of the region, and we keep changing our policy toward India and Pakistan, where people very much care about Kashmir. And this blend of American engagement and disengagement is destabilizing.

The old alliance

One major point of concern for the United States has always been the extensive border dispute between India and China that dates back to the British colonial era. This is an extremely long border with many disputed points and was the subject of a war in 1962, right around the time of the Sino-Soviet split at the height of the Cold War.

When India was partitioned along religious lines as part of decolonization, a consolidated Muslim state was created, even though its two parts were disconnected. So at the time, what is now Bangladesh was known as East Pakistan and was part of the same country as contemporary Pakistan. This setup generated enormous tensions within Pakistan.

China aligned itself diplomatically with Pakistan against India, and India aligned itself diplomatically with the USSR. The United States is far away from all of this, but the logic of the Cold War was that we should align with Pakistan.

As a result, when Bangladeshi leaders started pushing for independence and Pakistan’s military dictatorship launched a genocidal war against them, the Nixon administration stood with Pakistan.1 One should not overstate the American government’s role in these events, which reflected a regional logic that nobody in Washington was particularly invested in. But that logic compelled the Indian government to intervene against Pakistan, not so much out of humanitarian concern (though they did want to stop refugee flows) as because it offered an opportunity to take Pakistan down a peg. Nixon didn’t want that and supplied weapons to Pakistan as the crisis escalated, and continued to do so while leaving Congress in the dark during the worst of Pakistani brutality.

This particular set of decisions drew plenty of criticism in the United States, but over the next 20 years, the same basic diplomatic alignment continued.

Notably, when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the United States used Pakistan as a critical intermediary to supply Islamist rebels. Not only was the enemy of our enemy our friend, the relationship with Pakistan was longstanding, as was the animosity between Pakistan and the USSR via the Soviet alignment with India.

But the Cold War ended a long time ago and the US-China relationship has been transforming as well. And that’s put pressure on this entire logic.

The big slow switch

In retrospect, the 1990s were a time of drift in geopolitics.

The Clinton administration was basically trying to get along with everybody, welcoming China into the World Trade Organization and doing friendly photo ops with Boris Yeltsin, but also expanding NATO and also doing NAFTA. There was a prevailing concept of an “international community” squaring off against a handful of “rogue states” like Iran, Iraq, and North Korea, who were defined by their defiance of global nonproliferation norms.

India and Pakistan were flies in the ointment in that regard, too big and too important to dismiss as “rogues,” but not party to the proliferation rules.

There was, however, a clear emerging logic that the United States should try to ally with India — a fellow democracy — against China, an emerging potential rival. But the hope at the time was that increased trade with China would lead to political reform, so this idea was on the back-burner.

Then came 9/11, a turn of events that led to heightened scrutiny of the Pakistani government’s ties to Islamist militant groups, but also a practical dependence on Pakistan to facilitate the war in Afghanistan. I think it’s fair to say that both the Bush and Obama administrations found the Pakistani state’s relationship to the Taliban and other militant groups unsatisfactory. But they also never really came up with a solution to the problem.

I always thought that most criticism of the Biden Administration for the withdrawal from Afghanistan involved a lot of missing the forest for the trees.

Both Biden and Trump wanted to withdraw because sustaining an indefinite American military presence in Kabul required indefinite dependence on the unreliable Pakistani government as a key partner. At the same time, Pakistan never committed to severing their relationship with the Taliban, because they never believed the US would stick around for the long haul. As the US-China relationship grew increasingly contentious, it became increasingly important to cultivate an alliance with India, and that meant cutting bait on Afghanistan.

And this mostly worked. Trump had a big reception in India near the end of his first term, Biden hosted a state dinner for Prime Minister Modi, and Trump did the same. During a contentious time in American politics, a rare dose of bipartisanship underlies steady efforts to increase American arms sales to India.

The American policy goal here is to build up a counterweight to China, but the result has been, in part, to shift the balance of power vis-à-vis Pakistan decisively in India’s favor.

The shifting tide

Here, again, there is more at work than American policy.

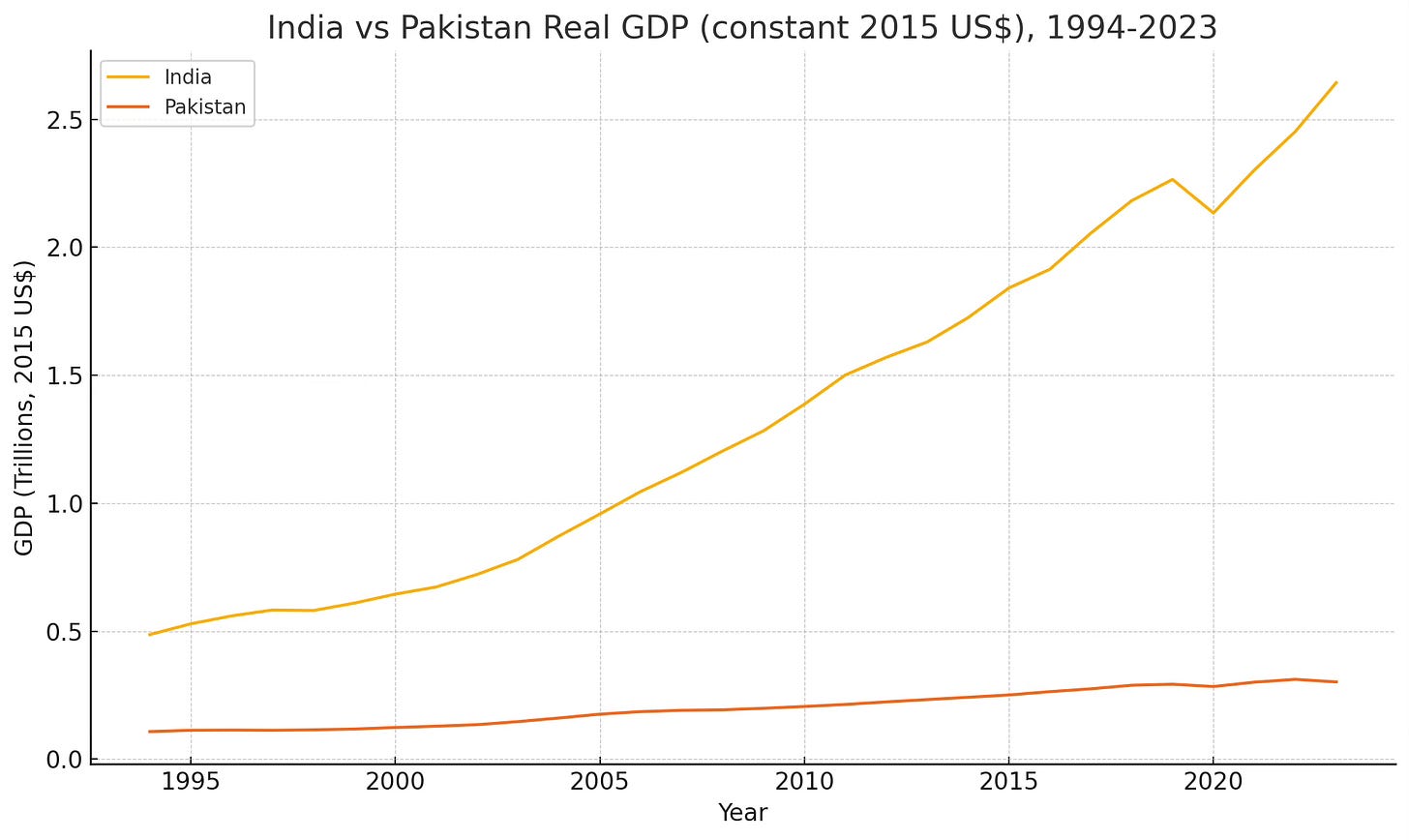

In 1991, Pakistan — though smaller than India — was 65 percent richer in per capita terms. Today, though India is still a fairly poor country, it’s richer than Pakistan on a per person basis, which means it has a dramatically larger economy.

As a result, India’s total defense budget is eight or nine times larger than Pakistan’s, and they’re able to translate that into a diverse base of military hardware. India still buys plenty of Russian equipment, they have advanced French fighters, and they have their big range of new American defense acquisition deals.

Pakistan is not exactly isolated in the world, but their economy is a basket case, and they’ve become reliant on China as a source of military equipment. Noah Smith wrote a piece last year making the point that Pakistan should try to quash the beef with India, stop stretching its fiscal resources on military equipment, and try to get more trade going with both India and Bangladesh. This seems like good advice, but every country has its own internal politics to contend with, and I think Pakistan is in an unusually difficult position, because the foundational concept of the state is that Muslim-majority land shouldn’t be ruled by India.

Meanwhile, everyone who’s anyone in American foreign policy circles is calling for closer ties to India. A report for the Atlantic Council says, “The era of great power competition calls for Great Power Partnerships.” CSIS wants us to move beyond “building trust” to various deeper forms of collaboration. CNAS, similarly, has a new program to identify ways to “enhance military cooperation with a focus on defense innovation, undersea operations, intelligence sharing, and joint naval exercises.”

The upshot is that India feels much less need for restraint than it has in the past, and Pakistan is much more reliant on pure nuclear deterrence.

Ideally someone would do something

This is, obviously, a dangerous situation that American policy is not fully responsible for, but has contributed to.

I think most people underrate the extent to which the current US-China cold war dynamic drastically increases the odds of wars around the world. Not because either the United States or China particularly wants to see wars break out, but because actors everywhere are increasingly able to rely on US-China antagonism to ensure they have support, almost regardless of what they do. Just as the US once fueled a genocidal attack on Bangladesh because the people undertaking it were anti-Soviet, we’re now backing an increase in Indian military capacity against Pakistan for reasons that have nothing to do with Pakistan.

In the flare-ups of this conflict in the early aughts, the United States tried to mediate and keep a lid on things. Some of that had to do with practical aspects of regional policy and management of the War on Terror. Some of it was a sense of American indispensability and our desire to be involved in big problems.

Trump, personally, is not knowledgable about world affairs or inclined to dive into the details of things or expend significant amounts of time and energy working on problems.

And beyond his personal shortcomings, he has a philosophical disagreement with the notion that the United States should play a constructive role in the world. So while obviously nobody wants this conflict to spiral out of control, it’s not clear that anyone with weight is working hard to avoid that outcome. Ravi Agrawal, the editor in chief of Foreign Policy and the author of a book on India, offered as his optimistic take that “in a jingoistic, siloed media ecosystem, both sides may be able to claim victory—whether real or imagined—and pull back from the brink.”

This seems to more or less be happening, which is certainly better than the alternative as escalation. But as far as optimistic takes go, this is not very optimistic! Nothing about the underlying dispute over Kashmir or Pakistan’s relationship with militant groups has been resolved. The ceasefire might hold (we hope) or it might not, but even if it does the conditions for renewed conflict are just lying around. And while the details are not particularly our business or something that we care about, our larger geopolitical schemes do impact the situation and it would be a lot better to try to impact it constructively.

If you want to read a book about this, Gary Bass’s “The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide” is the one to pick up.

This is an important and informative, but biased and flawed, argument.

Firstly, this post is way too soft on Clinton, Bush, and Obama for our cynical (and seemingly counterproductive, at best) relationship with Pakistan. Easy to say in retrospect, I know, but the idea that Pakistan fit into the category of "with friends like these..." was salient even at the time. Pakistan clearly had its hands dirty in terrorism targeting America and American interests even back in the 1990s. Not to mention their *central* role in nuclear proliferation at the time!

And, secondly, this essay bizarrely doesn't even acknowledge that the Trump Administration (contra brand) not only engaged with this topic, but actually brokered the cease-fire! That certainly makes the Trump-as-isolationist framing more complex and reveals something that's been discussed about the Trump Administration's foreign policy: that it contains multitudes, at best, and is an incoherent mess, at worst. Either way, *somebody* in the Trump Admistration decided that this was important enough to quash very quickly.

Also, wouldn't it be interesting and important to acknowledge the scale of this clash!? It was allegedly actually the biggest dogfight since WWII! At least two top-of-the-line Indian air force jets downed in the melee that involved over a hundred planes. That's paradigm-shifting. Much like the Ukraine land war has been.

Random tidbit of information:

In spite of the Nixon administration screwing over Bangladesh, Bangladeshis seems to like us pretty well while Pakistanis hate us. Go figure.

https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2024/06/11/views-of-the-u-s/

https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2015/06/23/1-americas-global-image/

Also, up until recently (I haven't seen data for 2024), Bangladeshi Americans were possibly the most Democrat-aligned ethnic group in America, dating back to Nixon screwing them over and Ted Kennedy standing up for them. So they seem to hold animosity towards Nixon specifically rather than America as a whole. 🤷