Bad news from the New Cold War

The return of great power conflict means more humanitarian disasters

A very long time ago, I wrote a book about foreign policy. It was mostly about stuff that nobody cares about anymore and probably doesn’t hold up very well.

But one thing I wrote that I think both holds up and has become a bit underrated is that if the world were to shift to a polarized US/China Cold War dynamic, the humanitarian consequences for poor countries would be dire.

At the time, there was a lot of interest in the question of whether the United States should try to limit itself to defensive wars and military actions authorized by the UN Security Council, or whether launching other kinds of wars was ever justified. The Bush administration, of course, believed in preventative war against Iraq. But another view — encapsulated in this 2004 article by Lee Feinberg and Anne-Marie Slaughter, both of whom went on to serve in the Obama administration — suggested that we needed a humanitarian exemption:

In the name of protecting state sovereignty, international law traditionally prohibited states from intervening in one another’s affairs, with military force or otherwise. But members of the human rights and humanitarian protection communities came to realize that, in light of the humanitarian catastrophes of the 1990s, from famine to genocide to ethnic cleansing, those principles will not do. The world could no longer sit and wait, reacting only when a crisis caused massive human suffering or spilled across borders, posing more conventional threats to international peace and security.

My view at the time was that this humanitarian intervention impulse was short-sighted and self-defeating. The cost effectiveness of military intervention is terrible compared to something like GiveDirectly. But beyond that, the principle would preclude any kind of cooperative coexistence with Russia and China and guarantee an international competition dynamic that had dire humanitarian consequences.

I honestly do not know enough about subsequent events in Moscow and Beijing to give an informed opinion as to whether the Obama administration’s dalliances with the Feinberg/Slaughter view of this in Libya and, to an extent, Syria played a meaningful role in the downward spiral of relations with the United States. I suspect that it was cooked one way or another by Xi Jinping’s transformation of the CCP oligarchy into a personalistic dictatorship.

But whatever the cause of the polarization of international relations, it’s clearly been a major driver of bad humanitarian outcomes. Mark Leon Goldberg’s great recent overview of the basic state of humanitarian crises gets at this dynamic, noting that “tensions between the West, Russia, and China have undermined the Security Council’s ability to resolve conflicts,” so this basic building block of the UN essentially doesn’t work anymore.

That’s important. But structurally, geopolitical tension doesn’t just undermine the Security Council’s ability to resolve conflict. It adds fuel to a fire that threatens to ensure localized disputes become increasingly intractable and brutal.

Humanitarian needs are driven by armed conflict

This graphic is from the latest edition of the UN’s Global Humanitarian Overview. It lays out the unmet funding needs to address humanitarian emergencies in several dozen countries. Something you see very quickly is that the biggest requests — for Sudan, Syria, Palestine — are driven by wars.

We’re not talking about natural disasters or famine induced by bad weather.

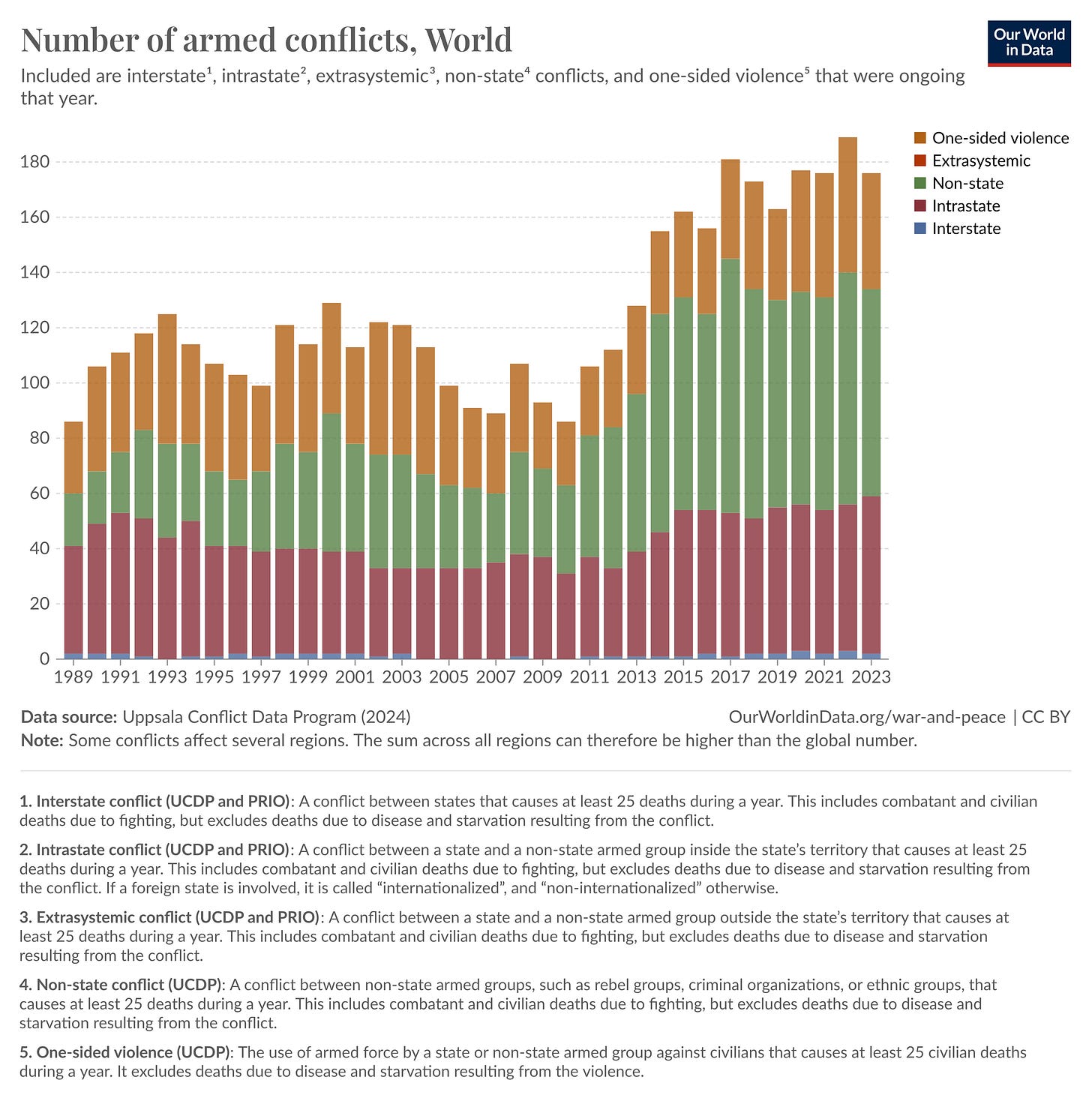

And while the violence does, of course, directly threaten civilian lives, it also disrupts economic activity and markets, placing large numbers of people in extremely precarious circumstances, and then further endangers them by making it difficult to disperse aid. In practice, blocking aid has become a routine tactic of war — whether to try to starve the enemy’s civilian population or because the easiest way to ensure that zero items of military use are smuggled in an aid convoy is to allow no convoys. A big part of what we’re seeing in terms of increased humanitarian needs is simply an increase in the number of armed conflicts.

So far, only about 43 percent of the roughly $50 billion that’s needed to address these emergencies has been met. As Goldberg writes, “this has resulted in cuts to services, including an 80 percent reduction in food assistance in Syria, cuts to water and sanitation services in cholera-plagued Yemen, and surging hunger among Sudanese refugees in Chad,” among other things.

Foreign aid spending is never a popular cause (it’s often the only specific spending cut that polls well). But I think governments around the world have also seen recently that the politics of large-scale refugee and asylum flows are awful. Plenty of political movements around the world are explicitly built on callous indifference to the fate of foreigners. But I think people who don’t feel that way may ultimately have an easier time trying to fight for money than for increased immigration. And, of course, movements that have made political hay out of anti-immigration politics might find some upside in owning the libs by demonstrating that they’re not totally indifferent to the problems of the world by putting some money into this stuff (or they can act like Ron Paul and Elon Musk and call for totally eliminating it).

But it’s also worth understanding the tragic roots of this uptick in violence.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.