Ride-sharing apps are good, actually

The real "cautionary tale" is that the old taxi cartels were bad

Before we get to today’s post, we want to introduce two new Slow Boring staff members. Feel free to say hello in the comments!

Caroline Sutton is the assistant editor at Slow Boring, where she fact-checks, copyedits, and provides other editorial support. Previously, she edited policy and politics content at the Tony Blair Institute in London and wrote about US politics and foreign policy at Interzine, a digital magazine. She holds degrees from New York University and the London School of Economics. Originally from a small town in Kansas, she’s spent much of her adult life in Europe. These days, she’s usually in coastal North Carolina when not in DC. She’s especially interested in making smart policy ideas accessible — and exciting — to more people.

Halina Bennet is a writing fellow at Slow Boring. She’s a journalist whose reporting has taken her from Maine to Massachusetts to Manhattan. Most recently, she contributed to The New York Times’ coverage of student protests, visa policy, and major national events, including the Florida State University shooting and Hurricane Helene. Halina graduated from Bowdoin College in 2023, where she studied English and history and was a proud writer and editor for the college’s student-run newspaper. Her interest in how policy shapes people's lives began in Colorado, where she spent her childhood traveling her home state for her dad’s work as a public official. In her free time, Halina reads fiction, attends live music and theater, skis and hikes when she’s home and calls her sisters often. She’s excited to join the Slow Boring team and looks forward to helping expand the reporting!

When Uber came to DC in 2011, I hailed it as a clever arbitrage around municipal taxi regulations, which I thought were bad. It turns out that there’s actually more to the company than pure arbitrage.

I’ve spent my whole life in dense cities where hailing a cab is not a huge practical problem. Yes, in DC, you would often have to walk a few blocks toward a major commercial corridor to do it. But that never felt like a huge deal. The app-and-GPS aspect of Uber, in other words, struck me as at best a minor convenience. The real win was that the service functioned as an end-around play to evade regulatory restrictions on taxi supply.

These days, of course, the notion that you might need to walk several blocks and stand in the rain, hoping a cab will cruise by, seems perverse.

The app-based hailing model that Uber and Lyft and Bolt use makes it feasible to operate in places that aren’t like New York, DC, or Boston. You can visit an auto-oriented city like Nashville or Austin, stay in a hotel downtown, mostly walk places, and then grab a ride to make a few visits to more peripheral locations, saving yourself the trouble of renting a car. Or you can go out drinking in Los Angeles and get a convenient ride home without a designated driver. When traveling abroad, it used to be hard to communicate with cab drivers across language barriers — today, there’s an app for that.

App-based ride hailing is not a solution to systemic problems with American land use and transportation policy, but it has had a genuinely large and overwhelmingly positive impact on American life in ways that absolutely do relate to the underlying technology. Yet it’s also true that the regulatory arbitrage aspect of this is a big deal. It used to be the case that taxi markets were cozy cartels with high margins and extremely limited supply. Outside of a handful of dense cities, the whole model was built around bilking visitors traveling to and from the airport.

What’s sobering, though, is the fact that to some people, this successful act of regulatory arbitrage doesn’t show that the old taxi cartels were bad — it shows that Uber is bad.

Hilary Allen, an American University law professor, wrote an article for the Law and Political Economy blog recently about why venture capitalists are bad, and she held up Uber specifically as an illustration:

For many readers of this blog, Uber represents a cautionary tale. While the company attributed its initial success to cutting-edge technology—such as dynamic pricing, matching algorithms, real-time data—subsequent analysis has demonstrated that its growth was largely driven by ignoring, breaking, and then bending taxi regulations to suit its business model.

What I want to talk about here is not Allen’s forward-looking argument, which focuses largely on fintech issues. But the breezy way in which she asserts that Uber is a “cautionary tale” and assumes her audience will agree without argumentation. She thinks the fact that Uber busted up the old regulatory system and got a whole new category of companies legalized is a dangerous precedent. I think it’s good!

Because even though the law and political economy movement is not exactly a household name, this group exerts massive intellectual influence. Lina Khan and other members of the “Yale Law School school of economics” with ties to the movement played major roles in the Biden administration. LPE-inflected ideas are shaping much of the thinking in the anti-neoliberalism/anti-abundance space. And “Is Uber bad or were taxi cartels bad?” is a pretty good heuristic for thinking about where you stand on these larger debates.

The anti-economics movement in American law schools

The term “political economy” has kind of a funny history.

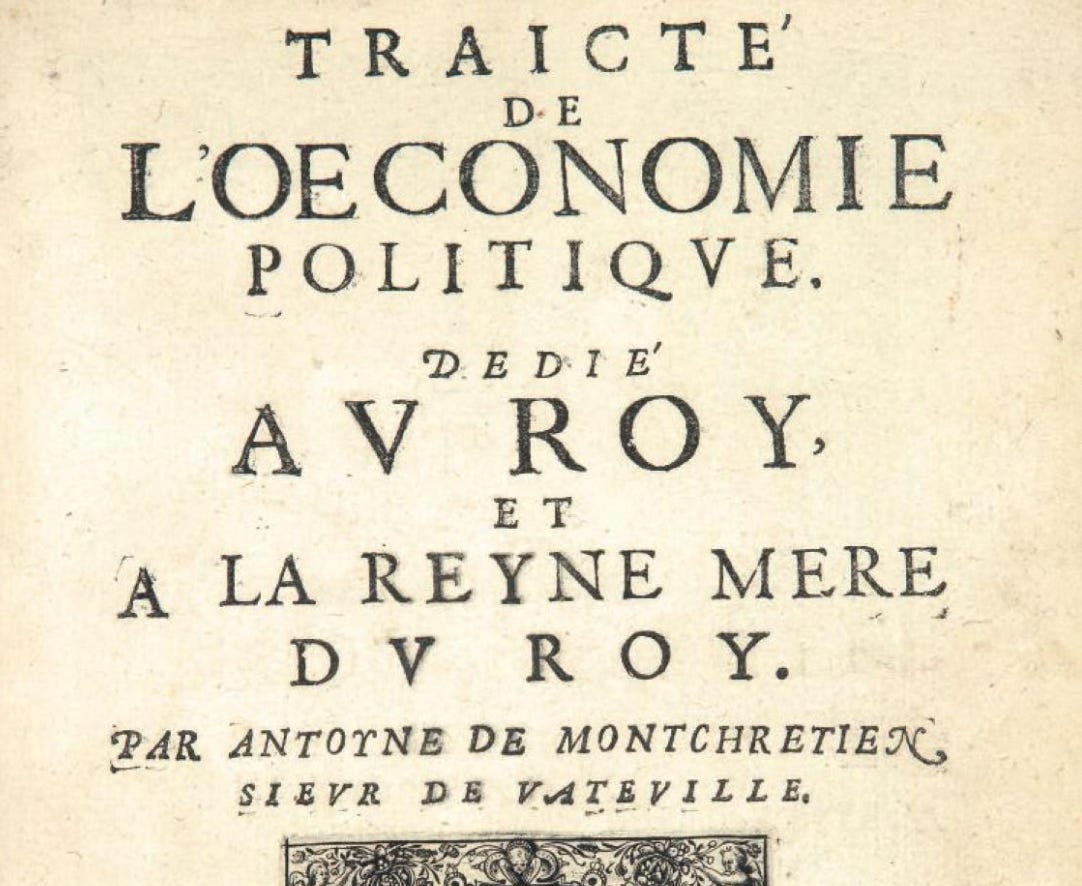

Figures like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Thomas Malthus, who we retroactively label as classical economists, did not use the word “economics.” They instead talked about “political economy,” a term they picked up from some French guys who were following in the footsteps of Antoine de Montchretien.

For a long time, “political economy” did not denote a specific viewpoint. Smith wrote political economy, and so did Karl Marx. It was simply what you wrote about when you wrote about economic policy.

Eventually, though, the economics profession developed. And while economists obviously disagree about a lot of things, mainstream economists have converged on a somewhat limited range of disagreements. If you ask Tyler Cowen and Paul Krugman about economic policy, they will probably not find a lot of consensus. But they will analyze questions using similar tool kits. Neither of them will endorse rent control or Trump’s tariffs. They don’t believe that “greedflation” is a useful analytic framework.

Economics is not a right-wing discipline per se; most economists are Democrats. But economics departments are less left-wing than other academic departments, and the discipline has a tendency to cut against far-left economic policy views.

The study of economics emphasizes the fact that life is not zero-sum, but it does feature tradeoffs. Economists do not believe that successful entrepreneurs always become rich simply by exploiting lower-paid workers. But they understand that there are tradeoffs inherent to tax and regulatory policy, which means efforts to help one group of people likely have meaningful downsides for others. People on the left generally believe that zero-sum conflict between the rich and everyone else is very important, but outside the sphere of class conflict, they don’t worry that much about tradeoffs.

People who want to talk about the subject matter of economic policy but who don’t have economics PhDs and/or don’t like the basic analytic frameworks used by economists started to use the phrase “political economy” to describe their anti-economics analytic approaches.

Beginning in the 1960s, but really gaining steam in the 1970s and 1980s, there was a big push under the heading “law and economics” to get judges and courts and regulators and legal analysts to incorporate economics into their analysis. One of the pioneering works of YIMBY scholarship is David Schleicher’s “The City as a Law and Economics Subject,” calling on scholars of land use law to think more seriously about research findings in agglomeration economics.

The “law and political economy” project, by contrast, is a push by left-wing legal scholars to do the reverse of — they argue that regulators should stop caring about economic analysis.

This school of thought got a major political boost from the growing prominence of the software industry. A lot of normal citizens, journalists, and elected officials all correctly perceived that the rise of smartphones and social media poses questions for regulatory policy that are beyond the scope of economic efficiency considerations. But that doesn’t mean we should abandon economic analysis entirely.

And I think this Uber example is important precisely for that reason. When we’re talking about LPE and critics of “neoliberalism” and “big tech,” we’re not talking about people who are worried that Instagram is making teenagers depressed. We’re talking about people who think it’s bad that apps broke the power of taxi cartels.

Breaking taxi cartels is good

The taxi industry as a whole is not that large or important in the grand scheme of things. But the dynamics around ride-hailing really do, I think, illustrate the core differences between economic analysis and the LPE worldview in which Uber serves as a cautionary tale.

Historically, the taxi market did not feature any large companies or other exemplars of corporate power. And while there may well have been a billionaire somewhere in America who owned a taxi company, I’m pretty sure that nobody became billionaire-rich in the taxi game. What we had instead was a highly fragmented landscape of localized businesses. If your view is that antitrust policy’s goal should be to stop companies from being big, the taxi situation was great. But if you believe the goal should be to promote competitive markets with high output and good prices, then it was terrible, because the taxi industry had massive regulatory barriers to entry. Regulatory barriers raise prices, but they also generate substantial deadweight loss. In the case of the taxi market, economic resources are redistributed away from taxi riders and to the owners of taxi companies or taxi medallions, but that redistributive bucket is leaky.

Exactly as Allen and other critics charge, Uber essentially tore down these barriers to entry by relying on VC financing to operate in legal gray areas and, eventually, to win regulatory and political fights that couldn’t be won without those deep pockets.

Uber also generates tons of fine-grained data about prices paid and wages earned. This data allows you to estimate the consumer surplus unlocked by Uber and to see that drivers really value the ability to set their own hours. Ubers also have a higher capacity utilization than pre-Uber taxis — i.e., someone is actually riding in the car a larger share of the time — so it’s not just that the number of available cabs increased, they’re being used more efficiently. Making cabs more available reduced drunk driving deaths, which is good, though it does also have downsides like more traffic congestion. There was early optimism that ride-hailing might put a big dent in the well-known phenomenon of racial discrimination in cab pickups. This was true in some cases, but there is an ongoing problem of discrimination against people with stereotypically Black names. It turns out, though, that a small tweak to the driver-side user interface can fix this.

All things considered, this is a great track record! The rise of ride-hailing apps did not usher in a utopian era, but on average, things got better for most people. The increased traffic congestion is a serious downside, but note that this is a downside that occurs precisely because the product is making people’s lives better. As transportation technology continues to improve, with self-driving cars, for example, managing congestion through pricing will only become more urgent. But again, this happens because things are getting better. If you made everyone’s car worse, people would drive less and traffic might ameliorate, but that would still be bad, all things considered.

Note that while nothing about “the invention of ride-hailing apps made life better” is antithetical to solid progressive ideas like progressive taxation and a social safety net, it is antithetical to core elements of the anti-neoliberalism push.

The bad guys in this instance were not the richest people in America or huge corporations wielding concentrated power — they were a disaggregated network of largely anonymous small business owners. We have more competition now, but also a marketplace that’s dominated by a much smaller number of large global companies. And that’s good!

Economics is an important part of economic policy

When people like the Revolving Door Project’s Jeff Hauser rail against Kamala Harris’s brother-in-law for working at Uber, or when the LPE crowd tells us that the failure of taxi cartels to strangle Uber in the crib is a “cautionary tale,” I think we should take them seriously.

If you personally feel that your life would be better off without ride-hailing companies, then I probably can’t talk you out of that. Of course some people lost out financially from the competition; part of my point here is that unfortunately, not everyone who lost out was some kind of evil plutocrat. And I think that’s the important lesson: You get a much better economic policy outcomes if you actually do economic analysis, including tedious ideas about deadweight loss and consumer surplus, than if you do policy on the basis of vibes, naming villains, and hand-waving about “power.”

Which is not to deny that there are issues beyond economic analysis that are worth thinking about. Owning Twitter means that Elon Musk has a powerful platform at his disposal. Alphabet and Meta, in addition to their core financial function of selling ads, play critical roles in the overall epistemic environment. By the same token, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal are influential and important institutions in a way that is not captured by their financial value. There’s more to life than economics.

But economics is, nonetheless, an important part of economic policy. If you don’t take it seriously, you end up believing that Uber is bad when, in fact, it’s good. And if you empower people who want to take the economic analysis out of economic policy, we’re going to end up in some very bad policy places.

I think that both the Yglesias and the LPE sides of this debate are missing the point.

Uber was an end-run around regulations, whether those regulations were good and effective or bad and cartelish. It's trite to say "good regulations are good, bad regulations are bad", but that doesn't make it untrue.

US taxi regulations were bad; Uber broke the cartels by bending first the law and then the regulators to their will. But there are other places that had good regulations (e.g. London) found that Uber was flouting those regulations and in some cases have had to accept that they can't enforce perfectly reasonable laws.

It was easy to set up a new "mini-cab"* company in London. There were regulations (the drivers had to have criminal records checks and right-to-work checks to confirm they were legal immigrants and to exclude drivers who might be a danger to passengers) but calling for a ride (back when it was by telephone) in any car that was legal to have on the road had been allowed since the 1970s. There were even already apps before Uber even arrived in London, though Hailo had very few drivers when Uber London launched in 2012.

Uber repeatedly refused to comply with the pretty-minimal regulatory requirements of a London mini-cab, and in the early years, it was notorious as a place where drivers who had been fired by other mini-cab companies for cause (often for being a danger to passengers, or a danger on the roads) went to work precisely because Uber regarded the star-rating system as more important than pre-emptive regulations.

Uber London Limited did eventually settle with the regulator and now operates under exactly the same regulations as those in place before it was allowed.

* mini-cabs are not black cabs; they're normal cars, like Uber uses, and they are subject to a different and much looser set of regulations, they can use any car they like, they don't have to charge per the taximeter, but can agree a fee in advance, etc. The only restrictions are that they can't pick up passengers that hail them, they have to be dispatched to the passenger who calls for a cab or uses an app, and they also can't use taxi-only facilities (taxi-ranks, taxi-only areas at airports and stations, etc).

As a law professor myself, people should exercise some caution around our policy analyses. Most law professors don’t have Ph.Ds and don’t have training in quantitative methods. (This is thankfully starting to change. Alas, the fact that most law professors have scarcely actually practiced law has not changed.) We aren’t good at assessing whether the empirical research we rely upon is actually high quality.

Also, the vast majority of law reviews are not peer reviewed. And if they are, it’s by other law professors who usually have the same limitations as the author. Law review articles are selected and edited by law students, who know basically nothing and seldom provide substantive feedback. (This is obviously not their fault.)

I always check whether a law professor who’s stepping into economic policy debates (1) has training in economics, (2) co-wrote with someone who does, and/or (3) published in a peer reviewed journal. If not, it doesn’t necessarily mean the analysis is bad, just that it may not be as rigorous as you imagine.