Trump's tax plans mean higher mortgage interest rates

The Fed can't save us from a soaring deficit

The federal reserve did a 50 basis point interest rate cut last week, which I think was appropriate in the sense that they should’ve started cutting rates at the previous meeting and it’s good to catch up.

The consensus seems to be that more rate cuts will follow at the next few meetings, which I think suggests they should have given more serious consideration to an even larger rate cut at the most recent meeting. The Fed has a strong bias in favor of taking measured steps because they don’t like to reverse themselves, but I think that sometimes leads to mistakes. They should try to set rates at Meeting A such that a reasonable observer is genuinely uncertain what will happen at Meeting A+1 because risks are perfectly balanced. The Fed’s actually approach prioritizes predictability, but that means they’re stuck under-reacting to events as they occur. That’s what happened when the Fed raised rates to try to check inflation, and it may be happening now as they cut rates to try to keep a floor under the labor market as spending has decelerated.

Either way, though, interest rates seem to be heading downward.

And that’s welcome news. Inflation — a word that has a precise technical meaning for sound technical reasons — has fallen enormously since its peak. But one of the mechanisms through which inflation has fallen has been higher interest rates. Higher interest rates make it harder, in practice, to afford things like mortgages and cars, and from a basic “How am I doing?” standpoint, cheap money is preferable to expensive money.

But here I think America’s elected officials need a word of caution. If you’re interested in something like the interest rate on a 30-year mortgage, I would not expect the Federal Reserve to deliver salvation. There are basically two feasible routes to sustainably lower long-term interest rates: One is for the economy to fall into an actual recession, and the other is for the federal government to move in the direction of lower budget deficits. Unfortunately, right now, Kamala Harris is running on ideas that would moderately expand the deficit, while Donald Trump is running on ideas that would explode it.

Thinking about interest rate changes

I think most people tend to get a little tripped up in their thinking about how the Fed’s actions relate to long term interest rates.

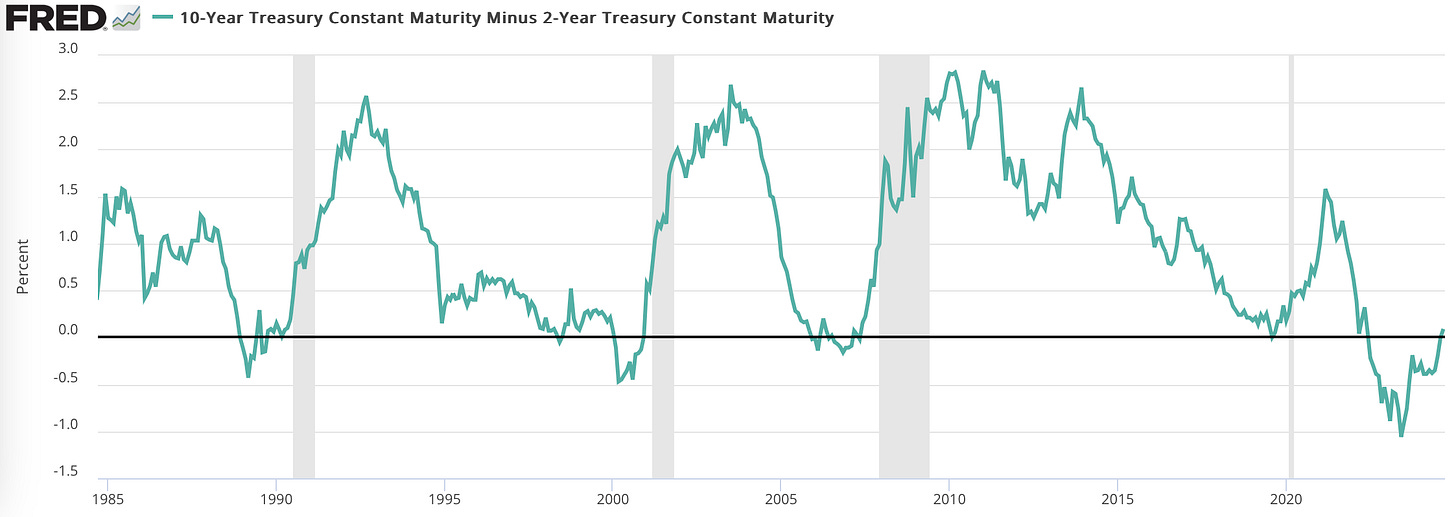

What the Fed directly manipulates is very short-term rates, rates that only really apply to things that banks deal with. But in a sense, the long term is just a series of short terms, so making short-term rates lower should have an influence on longer-term interest rates. That said, the nature of the relationship between rates of different durations changes over time. This is a chart showing the interest rate on a 10-year treasury bond versus the rate on a two-year bond. You can see that over the past 40 years, the spread never diverges by a very large number, and also that it is usually (but not always) a positive number.

You can do this comparison for any two durations, or you can plot a bunch of different durations simultaneously and get what they call a yield curve.

The upshot is that long-term interest rates are a function of both short-term rates, but also of how steep the yield curve is. Short-term rates are determined by the Fed, but what determines the yield curve?

Well, it’s complicated. But the curve is in part a response to financial markets anticipating demand conditions. One take on the prior meeting, when the Fed didn’t cut rates in the face of a deteriorating labor market, was that it was fine because long-term rates fell anyway. I don’t think that’s right. The Fed standing pat caused the yield curve to flatten because it signaled a hawkish central bank was going to starve the economy of demand. Conversely, when the 10-year bond yield went up in response to last week’s rate cut, that’s not a sign of policy failure — it’s a sign of reassurance.

To steal Scott Sumner’s line, you can’t reason from a price change. Oil prices could fall because oil became more plentiful, or because new technology reduced global demand for oil, or because a huge recession crushed global demand from oil. Just the fact that oil got cheaper doesn’t tell you very much. Similarly, you don’t just want long-term rates to go down, you want them to go down for good reasons.

Interest rates and the real world

We’re talking about interest rates on federal debt, but what most peopler really care about is things like interest rates on credit cards and home equity loans and mortgages. And while these rates are related, they respond differently to rate cuts from the Fed.

Both credit card1 interest rates and interest rates on home equity loans are functions of the prime rate. So what’s the prime rate?

The prime rate is the rate that a bank charges its very best corporate clients for short-term loans. Conventionally, a bank sets its prime rate to be about 3 percentage points above the federal funds rate, though in principle, it could be set to anything. The prime rate that is used for your credit card or your HELOC is a number that is published in the Wall Street Journal based on their survey of the 30 largest banks. When 23 banks out of 30 change their prime rate, the WSJ publishes a new number. And when the WSJ publishes a new number, most of the credit card interest rates in the country reset.

This sounds very fake — so fake, that I feel like most news articles don’t explain it at all. But that is, in fact, how the system works: The Fed changes interest rates which, by tradition, causes banks to shift their prime rates in a predictable way, which causes the WSJ to report a shift in prime rates, which causes credit card rates to shift.

Why don’t credit cards directly peg their interest rates to the Fed’s rates, if that would amount to the same thing? I sincerely do not know.

Mortgages are different, though. Most American mortgages have fixed rates over a long time horizon, typically 30 years. The process for setting these rates is less mechanical, but the basic idea is that issuing a conventional mortgage to a qualified buyer is a pretty safe loan. But it’s not as safe as a 30-year bond from the US government, so the mortgage rate ends up being a markup over the long-term bond interest rate.

And, as I mentioned above, that long-term bond rate can go down for different reasons.

If people think there’s going to be a lot of inflation, they’ll demand high interest rates on bonds and mortgage loans. Conversely, falling inflation expectations is a good reason for rates to go down.

But rates also go down if people expect a collapse in demand. That might be narrowly good for you if you’re looking to buy a house, but it’s bad news for the economy.

It’s also the case that rates might go up if the Treasury has to offer investors more money at its periodic bond auctions to roll over debt and cover the budget deficit. People sometimes worry about a “failed” Treasury auction where nobody buys the debt. We’re nowhere close to that sort of situation now. But we’re also no longer in the Great Recession, when there was always tons of demand for basically unlimited amounts of federal debt at any duration. Treasury has to pay more attention to what it’s doing at these auctions. The need to consistently sell large amounts of debt to keep the government going, combined with the somewhat inflationary impact of budget deficits, puts upward pressure on interest rates and prevents people from getting the cheap mortgages they crave.

Harris’ plans are unsatisfactory, Trump’s are catastrophic

Back when Obama was president and the economy would have benefitted from a larger budget deficit, the overwhelming conventional wisdom among frontline House members, red state Democratic Party Senators, and White House political operatives was that deficit reduction was a compelling message. Now that it’s 2024 and deficit reduction would be a good idea on the merits, almost everyone seems to have pivoted and decided that as a matter of pragmatic politics, you can’t promise spending cuts and anything Democrats do on the revenue side needs to finance new spending.

This kind of thinking doesn’t make sense under today’s circumstances, where most people are worried about interest rates.

And you see this as a Biden Administration sometimes goes in circles over the deployment of capital. On the one hand, they like to brag about the increased spending on the construction of manufacturing facilities that their industrial policy efforts has engendered. On the other hand, they’re worried about national housing scarcity and high mortgage rates and are proposing various tax credits that they hope will address this. But this is just using subsidies to redirect a limited pool of investment capital from one sector to another, and then getting mad that the first sector ended up with less capital, so now you want to subsidize it, too. What the country needs is more overall private sector investment facilitated by lower interest rates and less government borrowing.

In other words, if people couldn’t lend as much to the federal government, they’d lend more in the mortgage market, and rates would fall.

The Biden-Harris approach has been less-than-optimal, as I’ve argued many times in posts like “It’s Time for a Fiscal Commission” and “It’s the Right Time for Austerity.” At the same time, when it comes to the deficit, there is a very clear choice, and the choice is Harris, because Trump is running on an insane series of tax promises that would reduce federal revenue by more than $8 trillion over the next 10 years.

Some of these proposed cuts would mechanically accelerate bankruptcy of the Social Security Trust Fund and cut benefits, which violates all of Trump’s campaign promises (voters will hate it, but at least it partially offsets the fiscal impact). He’s also promising higher defense spending and more money for immigration enforcement. Importantly, one of Trump’s main policy goal is to reduce the size of the American workforce via curbing new immigration and “mass deportation,” so the per capita size of the debt burden will go up by even more.

The upshot is going to be some mix of much higher interest rates and doomsday cuts to programs for the poor.

It’s also important, from a pure fiscal sustainability point of view, to remember that if Trump wins, he’s much likelier to have control of Congress than Harris is if she wins. A Trump presidency will probably involve a GOP sweep, and they really will enact some (perhaps scaled down) version of this fiscal agenda. A Harris presidency will involve a lot of tense bipartisan negotiations, in which congressional Republicans will almost certainly block all her spending plans — both the ones I like and the ones that I like less. She will maybe succeed in forcing the expiration of some TCJA provisions, and the deficit will therefore go down a little. I wish we had a clearer vision from her of how she would make things better, but I think she’ll mostly avoid making things worse. Trump, by contrast, gives no indication that he understands how the situation has changed from 2017 and just answers all questions by invoking the magic of tariffs to make all tradeoffs and budgetary considerations go away. And I think we should be deeply concerned that running his playbook from a starting point of full employment is going to crush the ability to bring interest rates down.

The rate a customer pays on credit card debt floats up and down. You can’t “lock in” a favorable interest rate during a period of generally cheap interest, because credit card companies peg the rate they charge to be some number above the prime rate. What you see in credit card marketing material is APR, or annual percentage rate.

I feel like one of the most under-covered issues this cycle is the fact that the TCJA is going to expire.

I have wondered about the strategic merits of Harris saying your last paragraph somewhat explicitly. If you start from the premise that many undecided voters are double haters or at least double skeptics, I wonder if Harris has ground to gain by explicitly saying 1) I will likely not have a Dem trifecta, and therefore will be an honest bipartisan broker with Republicans in Congress to reach responsible oversight of America's finances and 2) DJT would not have to do so and would destroy our fiscal standing.

Harris is not an Obama level communicator (few are) but I always think pols leave stuff on the table by not saying more complex things for fear of lack of understanding. Harris should workshop how to explain in simplest terms why 2024 =/ 2017 economic conditions and why Trump's plans now would destroy the economy not save it.