It’s the right time for austerity

Keynesian ideas are symmetrical

Back in 1937, John Maynard Keynes warned Franklin Roosevelt that “the boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury.”

It’s a line I saw quoted a lot following America’s pivot to deficit reduction in 2010, and I believe that Keynes was correct when he wrote it and that the people who quoted this line in 2009 and 2011 and 2013 and 2015 were all correct. But in 2017 and 2019, I wouldn’t say exactly that we were in a “slump,” but it was completely correct to urge people to stay chill about budget deficits.1

People haunted by the downsides of Obama-era austerity policies played a huge role in shaping both the CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan. And while I think Bharat Ramamurti maybe glosses a bit too quickly over some errors and design flaws in ARP, his big picture point is correct: It was right to err on the side of more stimulative policy, and all things considered, ARP’s aggressive approach worked out well.

The thing that’s bothered me ever since ARP passed, though, isn’t the idea that Biden fucked up by doing too much stimulus — it’s the reluctance of progressives to acknowledge the implications of ARP working. If the boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury, then the slump is the right time for large-scale fiscal stimulus. But if you do that large-scale fiscal stimulus and end the slump, then it becomes the right time for austerity at the Treasury! This basic macroeconomic reality is either important or it isn’t.

I think that it is important, and that we should’ve been taking it much more seriously over the past three years.

Progressives right now are antsy for the Fed to cut interest rates. They increasingly believe that high interest rates are driving consumer dissatisfaction, even though inflation has fallen, and they rightly point out that high interest rates are a drag on housing construction (and all other kinds of construction) and thus hurt the supply side of the economy over the longer run. I think all that is right, and I also hope the Fed will cut interest rates soon. But the fact of the matter is that even though inflation has already fallen a lot, it is still above the two-percent target. So whether we get a rate cut at the April meeting or the June one or the July one, I just wouldn’t expect to see rates fall very much or very quickly in the absence of fiscal policy change.

What I mostly see is those who were big stimulus proponents in 2021 and 2011 now becoming monetary doves. But if you want lower interest rates, you need to take Keynes’ point much more seriously. The only saving grace for Democrats at the moment is that even though they are not taking this as seriously as they should, Trump is running on even worse ideas.

Trump’s fiscal agenda is terrible

Perceptions of the economic situation have improved over the past year, but people still think the economy is shitty, despite low unemployment and wages that are now rising faster than prices. Some of that is bitterness — wages are rising faster than prices now, but the opposite was true in 2021-2022. I think it is deeply unfair and irrational of the electorate to give Trump a pass on the economic problems of 2020 on the grounds that the pandemic was the root cause, but ignore the reality that the pandemic (or more specifically, the post-pandemic spending surge) was also the root case of the current inflation.

But it is what it is.

A less irrational aspect of consumer crankiness is explained in a new paper from Marijn Bolhuis, Judd Cramer, Karl Oskar Schulz, and Larry Summers titled “The Cost of Money is Part of the Cost of Living: New Evidence on the Consumer Sentiment Anomaly.” Their point is that while it’s true that the economy is doing really well right now according to standard macroeconomic variables about inflation and income, those standard variables ignore interest rates. Part of the reason that inflation came down is that interest rates went up. And if you incorporate interest rates along with other metrics, then it’s much easier to make sense of the consumer sentiment numbers.

A lot of my smart friends got excited by a summer 2023 analysis by someone going by Quantian on Twitter that reached this same conclusion.

I thought it was an interesting hypothesis, but the evidence he offered in support was a little underwhelming. The new Bolhuis et al. paper brings both international comparative data and some surprising-to-me information about what a large share of consumers are directly exposed to interest rates in a given year.

High interest rates are not just a problem right now, they also present a genuine problem for the future of the country. Real GDP was about 9 percent higher in Q3 of 2023 than it was in the quarter below the pandemic, but construction activity was lower.

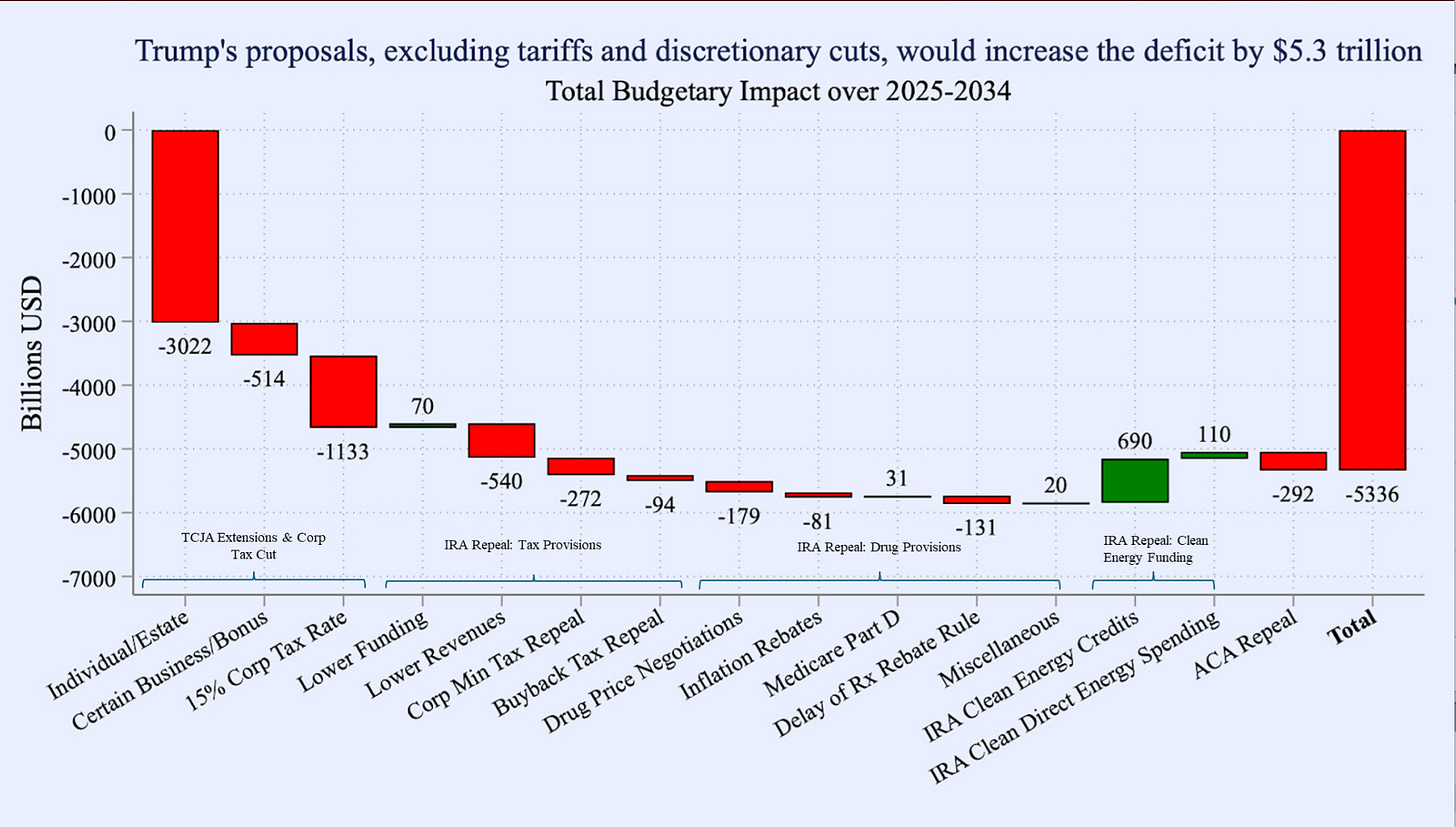

In the middle of this mess, Trump is proposing a gargantuan $5.3 trillion increase in the deficit that could be implemented via a budget reconciliation bill. That’s a lot!

Trump could, of course, offset this with cuts to the discretionary budget. But he’s promised to raise defense discretionary spending, so that’s not going to help. And leaving the military aside, he’d need something like a 50% cut to non-defense discretionary to offset all these tax increases. And that’s in a world where Trump is going to be asking for more money for a bunch of things related to immigration enforcement. So what are we talking about — closing half the national parks? Air traffic control? Highways? The FBI? Beyond that, appropriations bills are subject to filibuster and always end up being bipartisan deals. What normally happens to domestic discretionary is it goes down when a Democratic president needs to bargain with congressional Republicans but goes up when a Republican president needs to bargain with congressional Democrats.

The point is that while it’s hard to forecast exactly what will happen with Trump’s fiscal policy, it is going to mean higher deficits and higher interest rates, just as it did during his previous term in office. He has complained a lot about the altered macroeconomic situation under Biden, but he hasn’t adjusted any of his ideas accordingly. The only way out of the bind is for him to either go after Social Security and Medicare after all, or else add truly draconian Medicaid cuts to a reconciliation bill.

Biden’s fiscal agenda is okay

In contrast to Trump’s proposals, Biden has put together an FY 2025 budget request with numbers that add up: $3.3 trillion in net deficit reduction over a 10-year time horizon because he is raising more new revenue than he is spending on new programs.

Given the senate map, it strikes me as extremely unlikely that Democrats will have the congressional support to do anything like this, even if 2024 goes well for them. But this in turn exemplifies some of my frustration with Debbie Downer Progressives who want to insist that the strong economic recovery is, in fact, bad simply because the United States continues to fail to have an expansive welfare state. Biden could, if he wanted to, propose a less politically contentious budget that had smaller tax increases, dramatically less new spending, and more deficit reduction. If he did that, he would win more praise from deficit hawks and various business executives would like him more. He is instead running a platform that pairs deficit reduction with welfare state expansion because Democrats genuinely believe in that agenda, and if you believe in it, too, you should try to help them win elections so they can implement it.

At any rate, the upshot of all of this is that under Biden’s proposals, debt rises and then stabilizes at a level that is lower than the current baseline, whereas under the current baseline it just keeps going up and up.

This is a very responsible program compared to Trump’s. But it’s not an agenda that particularly says “I think reducing the deficit is a big deal.” It’s an agenda that says “I want to make sure things don’t get worse.” Which is a lot better than Trump’s plan to make things worse! But if you’re sitting around tearing your hair out about how you want interest rates to be lower, then it would make sense to prioritize deficit reduction more than this. And that would mean prioritizing it in practical legislative negotiations rather than abstract position-taking.

Time to tighten belts

In his 2010 State of the Union Address, Barack Obama said that “families across the country are tightening their belts and making tough decisions, the federal government should do the same.”

That was bad economics, and I believe that Obama’s economic team knew it was bad economics, but the political team really wanted to say it. If you look at contemporary polling, it’s still the case that voters want reassurance that Democrats care about the national debt, and they worry about the implications of the GOP tax cut agenda. But Biden is nowhere near Obama in terms of his deficit rhetoric, even though right now really is the time for the federal government to tighten its belt, precisely because families across the country aren’t doing that. The boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury.

When families tighten their belts, that means other families lose income, so you risk a downward spiral of belt-tightening that the government can helpfully avert by spending money. When the government spends money to avert the downward spiral, it would ideally spend the money on things that are useful. But the crucial Keynesian point is that in a downturn, inefficient spending is better than no spending at all because it keeps money circulating. And an equally crucial Keynesian point is that during a period of booming demand, the reverse logic applies.

Every federal construction project that’s a little bit bloated is consuming labor and material that could be building houses instead. Every middle manager working on an ineffective program is someone who could be managing a Target or a Chipotle. You don’t want to be inhumane with your cuts or eat society’s seed corn by eliminating genuinely useful expenditures. But you want heightened scrutiny on every dollar that is spent. You absolutely cannot balance the budget by tackling “waste” in federal spending. But there is a nonzero amount of waste, and at a time of low unemployment and worry about inflation and interest rates, trying to identify and eliminate it is a high-value activity.

This also extends to negotiating priorities. Senators are working on a deal that would attempt to extend some business tax breaks in exchange for some kind of increase in Child Tax Credit. In that kind of negotiation, you need to decide whether to err on the side of maximizing your side’s gains or to err on the side of minimizing your side’s giveaways. I love CTC expansion. And if the macroeconomic situation were different, I would urge Democrats to try to maximize what they can win on that, even if it means big giveaways on the corporate side. But the boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury, and that means now is the time to minimize giveaways, even if it means you minimize wins.

This austerity thinking also pertains to the regulatory state.

Something like the Jones Act, which pushes up freight costs, might seem non-optimal during a slump, but you can tell yourself that it’s supporting jobs and avoiding deflation. But during something like a boom, every anti-productivity rule on the books, no matter how small, is making it that much harder to have lower interest rates and faster real wage growth.

Another great old Keynesian slogan is “it takes a heap of Harberger Triangles to fill an Okun Gap” — a macroeconomics joke the point of which is that if your economy is depressed, it’s a lot easier to generate growth by doing stimulus (closing the Okun Gap) than by reducing deadweight loss (regulatory reforms to shrink or eliminate Harberger Triangles). But when you launch your administration with something like ARP, the point of which was to blast the Okun Gap to zero, there’s nothing left to do but focus on Harberger Triangles. Again, the point is not to criticize Biden’s economic policies, but to suggest that that his team has never fully internalized the idea that they genuinely accomplished what they set out to do. And that means they need to move on and act accordingly.

And, yes, for the record, that’s what I said about the Trump tax cuts.

I’m more and more convinced that the only thing that keeps Trump above 30% in polls is this false notion that he was/is competent at economic policy. Dems need to push back harder against this falsehood. He has managed his own inherited wealth terribly and his suggested policies will be pure poison to the US economy.

Are there any good examples of countries taking Keynesian economics seriously in a consistent way? Every country I can think of is either a permanent deficit hawk (Germany) or endlessly stimulating the economy (basically everyone else).