The weirdest academic controversy of 2023

The strange case of "Black metallurgists and the making of the Industrial Revolution"

One really cool thing about the Industrial Revolution is the extent to which different inventions across disparate areas played into each other.

Incredible progress was made on steam engines by Thomas Newcomen in 1712 and James Watt in 1764, and eventually steam engines would be used to power railroads, generating huge improvements in transportation time. But there’s no railroad without a lot of rails, and that doesn’t happen without a lot of iron. And, apparently, iron at large scale isn’t possible if you need to rely on charcoal to turn pig iron into cast iron.

Luckily, in 1783, an Englishman named Peter Onions was granted a patent for the “puddling process,” a way of turning pig iron into cast iron without using charcoal. Then the very next year, another English inventor named Henry Cort got a different patent for an even better version of the puddling process.

And this is where we get to one of the weirdest academic controversies I’ve ever seen play out: the case of Henry Cort versus enslaved Jamaican metallurgists.

Cort ended up with a very high reputation in some quarters. There was apparently an editorial in the Times in 1856 long after his death that called him “the father of the iron trade,” though a 1917 book refers to a totally different guy named John Wilkinson1 “the father of the iron trade.” The Cort Process was a step forward in puddling, but real commercialization didn’t come until further improvements by someone named Richard Crawshay and his colleagues at Merthyr Tydfil in Wales. This is all a bit obscure, but I think the important point to take away is that a lot of theoretical and practical improvements were made in ironworking in late-18th century Britain, with many people contributing.

At any rate, Cort was notable but seemingly not that notable. According to an article about him from the Hampshire County Council, “Given the importance of Henry Cort's contribution to the iron industry it is surprising that he does not have a high profile in Gosport.” But the article itself contains a potential explanation for Cort’s obscurity — he got involved in what sounds like a corrupt deal with a Royal Navy paymaster named Adam Jellicoe, and that ended very badly for Cort:

It looked as if all his investment was finally about to be rewarded when disaster struck. Adam Jellicoe died on 30th August 1789, some accounts say he committed suicide. Certainly he had been asked on the previous day to explain his private investment of public funds (from the Navy Pay Office) amounting to £27,000 lent to Cort.

Unfortunately for Cort, Jellicoe had pledged the two patents as security. These were seized by the Crown and subsequently valued at only £100. Amazingly Cort was held responsible for Adam's debt and was declared bankrupt. He had twelve children; a thirteenth was baptised at in February 1790 by which his name had disappeared from Gosport records. He died in London in 1800, a penniless undischarged bankrupt.

And so things stood until this past summer: Henry Cort was one of many noteworthy British engineers working in the late 18th century who contributed to the efflorescence of progress known as the Industrial Revolution. He died poor, and perhaps because he died poor, he did not leave any great legacy, even in his home town.2

But then came July of 2023 and the following headlines:

7/4: New Scientist: “English industrialist stole iron technique from Black metallurgists

7/5: The Guardian: “Industrial Revolution iron method ‘was taken from Jamaica by Briton’”

7/6: The Daily Mirror: “Pioneering Industrial Revolution method ‘taken from Jamaica and brought to Britain’”

7/26: Daily Echo: “Fareham's Henry Cort ‘stole iron technology from slaves’”

8/7: NPR’s Short Wave podcast (description here, transcript here): “Henry Cort stole his iron innovation from Black metallurgists in Jamaica”

This is a “big, if true” claim that turns out not to be true.

An English academic named Jenny Bulstrode published a paper, “Black metallurgists and the making of the industrial revolution,” that does not provide any evidence that Henry Cort stole his innovation from Black metallurgists in Jamaica, but still kinda claims that he did. Several media outlets ran aggressively with the story without really asking why the paper doesn’t provide any evidence for its thesis. The press coverage drew scrutiny to the original paper, with critics finding a number of flaws in it. There was some back and forth over those critiques, but even taking the Bulstrode paper at face value, there is no evidence of theft. And beyond that, it’s not clear that Cort’s invention was particularly or uniquely important.

The ordeal is interesting as a story of academic and journalistic malpractice, but in some ways, it’s even more interesting as an example of politically motivated social science without a clear theory of politics behind it.

Bulstrode’s article and the backlash

Bulstrode’s paper itself is quite odd. Suppose you’re a typical consumer of highbrow internet content who likes to talk about academic papers without actually having to read them. What do you do? Well, you scan abstracts. And, of course, academics know that people scan their abstracts. That’s what the abstract for — the authors state as clearly as they can what they believe their research shows, then people who are interested in that claim can read the full paper to find the evidence.

Metallurgy is the art and science of working metals, separating them from other substances and removing impurities. This paper is concerned with the Black metallurgists on whose art and science the intensive industries; military bases; and maritime networks of British enslaver colonialism in eighteenth-century Jamaica depended. To engage with these metallurgists on their own terms, the paper brings together oral histories and material culture with archives, newspapers, and published works. By focusing on the practices and priorities of Jamaica’s Black metallurgists, the significance and reach of their work begins to be uncovered. Between 1783 and 1784 financier turned ironmaster, Henry Cort, patented a process of rendering scrap metal into valuable bar iron. For this ‘discovery’, economic and industrial histories have lauded him as one of the revolutionary makers of the modern world. This paper shows how the myth of Henry Cort must be revised with the practices and purposes of Black metallurgists in Jamaica, who developed one of the most important innovations of the industrial revolution for their own reasons.

If I had discovered that a semi-famous English inventor had, in fact, stolen his invention from enslaved Jamaicans, I would put that in my abstract. But Bulstrode does not put that in her abstract. She instead insinuates it without saying it outright.

If you want to accuse Person A of stealing Invention X from Person B, you generally need to demonstrate two things:

Person B developed Invention X before Person A did.

Person A heard about Invention X from Person B.

Absent element (2), you have a case of independent discovery, which happens all the time. Bulstrode presents some very tenuous evidence of connections between Cort’s ironworks and Jamaica, much of which came into question under subsequent scrutiny.

But the really striking thing is that Bulstrode doesn’t have any evidence of point (1). She shows that a man named John Reeder operated a successful ironworks in Jamaica that worked with scrap iron and employed enslaved people. She also talks about how sugar plantations used machines with grooved rollers and how grooved rollers were also part of Cort’s ironworks. But obviously Jamaica was not the only island with sugar plantations, John Reeder was not the only guy with an ironworks, and while this speculation about the rollers is certainly interesting, she just didn’t actually turn up anything.

If you want the gory details, Anton Howes has the definitive rundown of the problems with Bulstrode’s argument, and Oliver Jelf shows that Bulstrode is misstating some of the documentary evidence regarding which ships went from Jamaica to where and when. But considering this issue in that level of detail is almost beside the point.

History without evidence

Bulstrode pointedly does not have any specific evidence for the claim that this technology was developed in Jamaica or that Cort learned of it from Jamaica. After the controversy raged for months, Amy Slaton and Tiago Saraiva, the editors of History & Technology, the journal where the article appeared, published a full-throated defense of Bulstrode’s work. But their defense concedes all the main points like “the historical record does not provide again any immediate proof that Cort knew about what was going on at Reeder’s foundry,” and for that matter we ourselves don’t know what was going on at Reeder’s foundry. The truth is, we simply don’t have any documentation of how Cort came up with his ideas or where they came from. There’s no “official story” from Cort to debunk; all we know is he filed his patent.

Into that space one can insert any number of vaguely plausible stories, and that’s essentially what Bulstrode did here. According to Slaton and Saraiva, that’s fine:

To make the case, as several of our correspondents have done, that ‘facts are facts’ (and that at bottom, Bulstrode is not adhering to what they see as the facts), is to deny a foundational tenet of humanities scholarship of the last several generations: That our perceptions of objectivity themselves derive from situated experiences. All historians necessarily select the conditions, actors and materialities that they find to be significant and thus, to constitute the events of the past.

We by no means hold that ‘fiction’ is a meaningless category – dishonesty and fabrication in academic scholarship are ethically unacceptable. But we do believe that what counts as accountability to our historical subjects, our readers and our own communities is not singular or to be dictated prior to engaging in historical study. If we are to confront the anti-Blackness of EuroAmerican intellectual traditions, as those have been explicated over the last century by DuBois, Fanon, and scholars of the subsequent generations we must grasp that what is experienced by dominant actors in EuroAmerican cultures as ‘empiricism’ is deeply conditioned by the predicating logics of colonialism and racial capitalism. To do otherwise is to reinstate older forms of profoundly selective historicism that support white domination.

It’s clearly true, as the journal editors say, that this is hardly a historically unique process. When the world was largely subject to European colonial domination, the dominators made up a lot of dubious theories of white racial superiority to Black and Asian people based on extremely scant evidence. So in a sense, making stuff up about the ingenuity of Jamaican metalworkers is just fair play. The high-minded thing to do at this point would be for me to denounce politicized science and call for rigor and truth-seeking, but instead I’ll just link to Noah Smith’s post about that and say something different.

A big part of what’s vexing to me about this is that while there are clearly political motives in play here, it’s not really clear what those motives are. It has something to do with the idea that racism is bad, but there isn’t a discernible political agenda at work.

Telling more diverse stories is good

It’s not particularly unusual to see political or ideological bias at work in people’s positive assertions about the world. But usually, the connection is pretty straightforward. Conservatives who tell you that tax cuts will pay for themselves are trying to advocate for tax cuts. Conservatives who tell you that climate change is a hoax are trying to argue for laxer environmental regulations. Leftists who tell you that climate change will lead to human extinction are trying to argue for stricter environmental regulations. When George W. Bush said Saddam Hussein had an advanced nuclear weapons program, it was because he wanted us to invade the country. When leftists said policing doesn’t prevent crime, they were pushing cuts to the police budget. When conservatives say that attaching work requirements to Medicaid will boost labor supply, they are pushing cuts to the Medicaid budget.

Which is just to say that while, unfortunately, people say untrue things for ideological reasons all the time, you can usually at least make sense of the ideology.

But why does this business about Cort even matter?

What Bulstrode says she’s doing in her paper is trying to “engage with these metallurgists on their own terms” and “focusing on the practices and priorities of Jamaica’s Black metallurgists.”

That seems like a valid and useful project. There are all kinds of historically marginalized groups of people whose stories haven’t been told over the years, usually because the people with the power to write the history books didn’t care about them. A good thing about our current era is that there’s much more interest in telling these stories and engaging with the activities and practices of the people who’ve historically been cast aside and ignored. It’s good to teach people that there’s more to human history than a procession of white men doing things. The civilizations of the Western Hemisphere were substantially built by enslaved people, and the project of understanding their activities on their own terms and explaining them to the world is valuable.

But straining to concoct theories connecting a particular Jamaican ironworks to a semi-obscure innovation in England actually violates the concept of taking the Jamaican metallurgists seriously on their own terms. Of course, if there actually were clear evidence that Cort had picked up his idea secondhand from Jamaica, that would be a noteworthy factual discovery. But there isn’t any such evidence, and straining to draw the connection undermines the sense that the world should learn about the actual lives and doings of actual subaltern people.

As a frame job, meanwhile, this exercise seems a little pointless. Cort died in poverty. There’s no Cort Foundation or Cort family fortune that you can shake down. Cort isn’t really that famous; his name only appeared once before in History & Technology. The high level of media interest in this theft charge, especially given the flimsiness of the evidence, suggests a very strong political motive. But there’s no coherent political agenda here, other than I guess vaguely trying to stick it to the man.

You solve present problems in the present

Even though I find history very interesting to study and read about, I think it tends to be somewhat overrated as an explanation of the economic present.

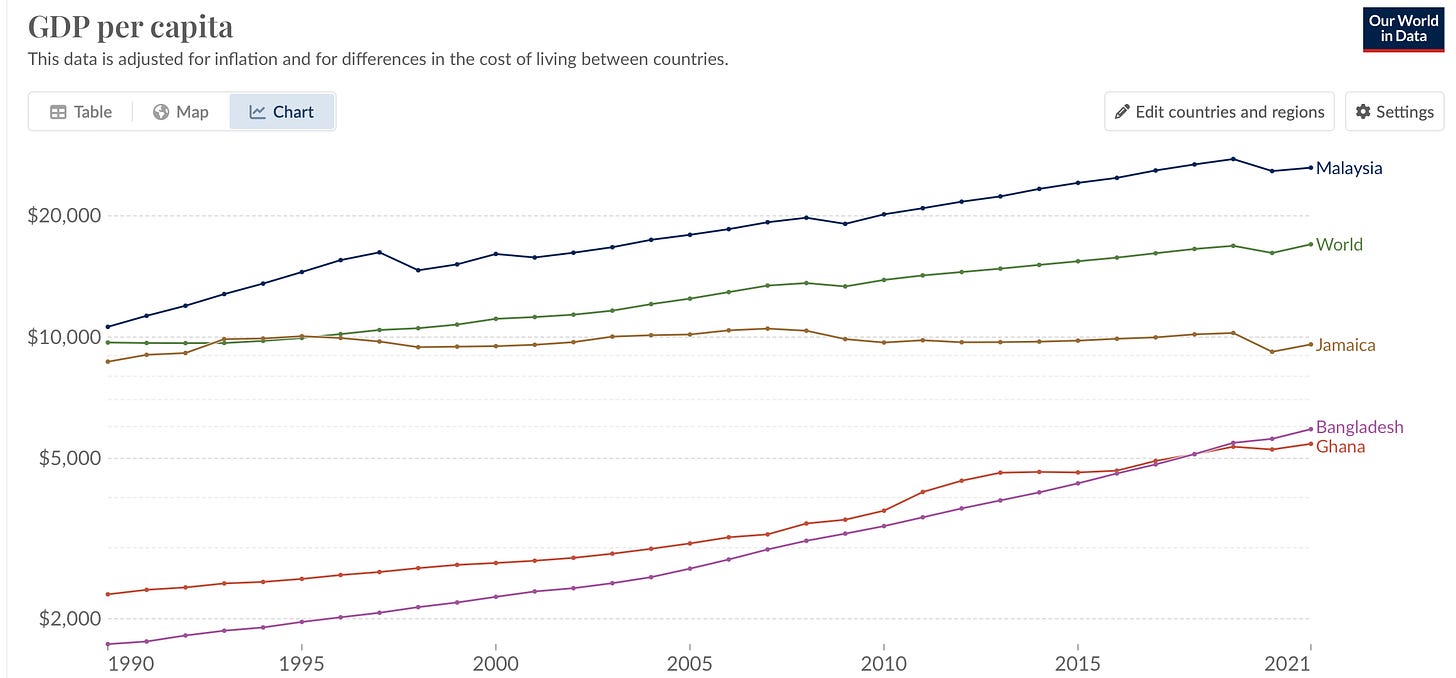

If you went back 30 years in time to ask what role British colonialism played in making Jamaica a poor country, you’d have to start with the fact that 30 years ago, Jamaica actually wasn’t poor — it was an average country. It became a “poor country” not in the distant colonial past, but over the past generation, as the world got richer and Jamaica stagnated.

To compare it to some other British colonies, Malaysia has gone from slightly richer than Jamaica to much richer, while Bangladesh and Ghana have narrowed the gap.

Will Ghana surpass Jamaica over the next 30 years? I have no idea. That will depend in part on things outside of Ghana’s control, like what happens in neighboring countries. And it will depend in part on whether Ghanaian policymakers make good choices. But the deep past just doesn’t explain everything. We’ve had enough rapid growth success stories over the past 70 years to know that it’s possible for poor countries to develop rapidly, but it’s also possible for countries to stagnate.

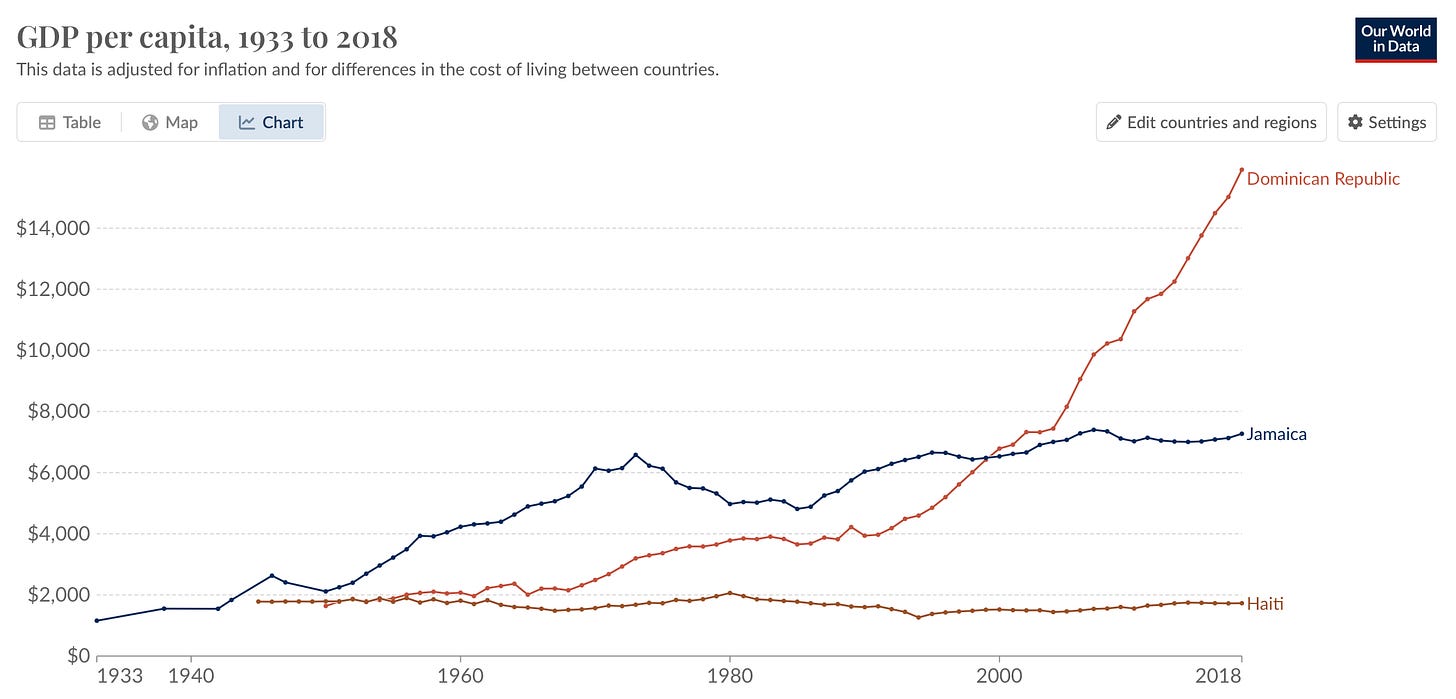

Even within the Caribbean region, consider three different countries populated largely by the descendants of enslaved people who worked on sugar plantations. As of the 1940s, Jamaica and Haiti and the Dominican Republic were all similarly poor, which you might reasonably attribute to their similar histories. But the economic trends have been wildly different since then.

None of this is to say that the economic problems of Jamaica or any other poor country are easy to solve. But the problems, in a profound way, really do lie in the present. If you want to use scholarship to help Jamaica, or any other country, you need to analyze its current situation and come up with some concrete ideas for positive change. If there are political barriers to implementing those ideas, you need to do political work — coalition-building, persuasion — to overcome those barriers. Accurate history is always welcome, because it’s good to know true things. But there’s no huge political stakes that make it worth trying to generate propaganda.

Slavery was very awful. The Industrial Revolution generated a lot of long-term human progress. And no amount of quibbling around Henry Cort will change either of those things or solve any of Jamaica’s problems.

Wilkinson did a bunch of iron-related stuff, including developing an improved blast furnace, figuring out how to manufacture several different useful machine tools out of cast iron, and was a bit of a pioneer in the idea that you could build iron bridges.

This story illustrates, I think, that contemporary policymaking probably overrates the role of direct financial incentives in driving invention and that we are probably relying too much on patents.

Disclaimer: I'm a PhD academic. History of Technology is one of my specialties, and I know some of the people in this article personally, including have worked for Amy Slaton. My book on the early history of radiation therapy was (favorably) reviewed in T&C.

That out of the way, I (predictably) view this controversy a little bit differently. I think it is emblematic of the problem of claim-creep and "stakes" that has afflicted the humanities throughout my career. This is basically an article about a person who had an interesting story about an understudied group. It would have been an interesting article. But, and this is important, no one would have cared about it, no one on this site would have read it, and it would not have made the news.

So instead this historian reached for a bigger, juicier claim, but one for which the evidentiary basis was much weaker. That claim, as Matt points out, wasn't even that significant: Cort's invention did not make or break the Industrial Revolution, and Cort wasn't that significant of a character in history. But obviously the bigger, juicier claim worked like a charm. Even if Bulstrode's reputation is publicly damaged, she is now a big-name academic that people have heard of. Whatever she publishes next will draw more attention. People on Slow Boring can name her. She will get job interviews from committees that include someone sympathetic to her claims.

My entire career included a non-stop admonition for people to find "stakes" for their claims: your story about early radiation therapy is great and all, but who cares? And my personal take was that it was a dumb question. You can make some stakes claims about the trajectory of bioethics and human experimentation--and I do--but honestly, I don't think the story matters THAT much. I think interesting stories are interesting, and humans have been engaged in storytelling for as long as there are humans, and people read those little plaques on the side of the road and the eleventh John Adams biography for that reason, rather than because every story has world-altering stakes.

But in a world where the humanities are consistently denigrated in favor of STEM--an utterly ridiculous discussion that happens in the comments on this very forum with disappointing regularity even though THE BIGGEST UNDERGRADUATE MAJOR BY FAR IS BUSINESS--it shouldn't surprise you that humanities people, instead of going quietly into that good night, try to elevate the importance of their own thing. Of course claim creep happens. People want to feel relevant and important, and right now their relative position in academia has been systematically down graded. Of course they inflate their work.

I want to be clear: I think this is all dumb. I know a lot of STEM people in academia, since my world has crossed theirs in a few different ways (first my academic work, then my shift into nursing), and the truth is that most STEM academics also aren't doing much of "significance" to the world. That's never how anything works. It's useful to discover that a potential drug molecule doesn't work, but you aren't getting a Nobel, my friend. So I honestly wish we could quit playing Hunger Games on all this. You want to feel significant? I compress people's chests to keep them from dying. Go do that. But the truth is that even that isn't very significant, except to that one person and some people close to them.

So I guess I really think this is a story about people's desire to be important, and humans are funny about that sort of thing. Bulstrode won. Maybe she also lost. It's a stupid game, fueled by comments like the ones made in this very forum that imagine the importance of the humanities department even as the Business School collects more tuition money.

Closing professional note: I haven't read the article--I was kind of busy finishing up nursing school and starting my practice career--so I don't have strong sense of how lousy the evidence is. But, HAVING NOT READ THE ARTICLE, I would say that technological innovations often move through networks of people who see people doing a thing some way or hear a story from a guy who met a guy or whatever, so it's not a strictly implausible claim. But you also can't prove that kind of stuff, and if you are getting over your skis on a hunch, you should probably either drop the claim or just say, "I'm likely over my skis here, but my sense is that one possibility is X because I read Y," or similar. I had to do both for my x-ray and radium tech book because there were some juicy professional fights. Bulstrode kind of covered her tracks by being vague enough to not make strictly disprovable claim, but she should have been more honest about just saying that this is a fun and totally unprovable possibility. On the other hand, maybe then no one on Slow Boring would ever have heard of her...

This has to make you wonder how much history, sociology, and "X studies" work is just total made up garbage that never gets challenged. I mean, this total made up garbage made headlines around the world, and people anchor their perceptions to the first thing they hear about something so it's likely that Cort's "theft" will become fact to some chunk of the population.