The Nobel Prize-winning case for a little bit of monopoly

Competition, like most things, has its limits.

Competition is good for consumers, not just because it gives us options, but because it fundamentally ensures that we’re getting a good deal. Items you purchase in highly competitive markets aren’t free — sometimes they’re quite expensive — but the price basically reflects the cost of production.

In a non-competitive market, with a monopolist or major barriers to entry, producers can secure enormous profits. But absent barriers to entry or shady tactics, enormous profits will attract new competitors, and those competitors will chip away at profits.

Indeed, a totally idealized competitive market features no economic profits at all. You still have accounting profits in the sense that revenue exceeds expenditure, but under conditions of perfect competition, that’s just recouping the cost of the initial investment.

Of course, in the real world, we rarely (if ever) see the sort of idealized perfect competition described in an economics textbook.

That’s not because the textbooks are wrong or economists are confused; it’s because perfect competition is a modeling exercise rather than an empirical claim. In a physics class, students learn to solve problems that involve objects moving on a frictionless plane. Frictionless planes don’t actually exist, but understanding how those frictionless systems operate does help you understand the motion of objects in the real world. By the same token, understanding how a basically hypothetical condition of perfect competition would work helps us to understand real world markets, which normally feature non-zero levels of competition and also varying degrees of monopoly power.

The obvious take on this is that more competition is better because that’s how everyone gets a better deal. But according to the winners of this year’s Nobel Prize in economics, that take isn’t entirely correct.

Half of the prize went to Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt for their work, dating from the early 1990s, formalizing ideas that go back to Joseph Schumpeter’s work on innovation. The notion of “creative destruction” is probably the best known idea associated with this work. But the most provocative is that while maximizing competition may serve consumers’ short-term interests, it’s not necessarily the be-all and end-all for long-term growth.

To understand why, we have to go back to the beginning.

The mystery of economic growth

Adam Smith’s 1776 magnum opus “An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations” is one of the most important books in the history of economics.

And 250 years later, its subject matter is still the core of what economists (and people conversant in conventional economic analysis) are particularly knowledgeable about: understanding what kind of policy regime leads to an efficient allocation of resources so as to minimize waste and maximize prosperity.

If you put a bunch of economists in charge of governing pretty much anything, they could identify policy reforms that would improve efficiency and make people better off. What’s more, these economists, regardless of partisan affiliations or ideological views, would almost certainly agree on a similar set of reforms. You might need to specify how much they should care about the distributional consequences of their choices, but for any given set of parameters, well-trained technocrats could definitely help you achieve those parameters in a growth-inducing way.

At the time Smith wrote, there was already a strong case that not only were welfare-enhancing policy reforms a good idea, but that understanding this subject would help answer the titular question of his book: why are some nations wealthier than others?

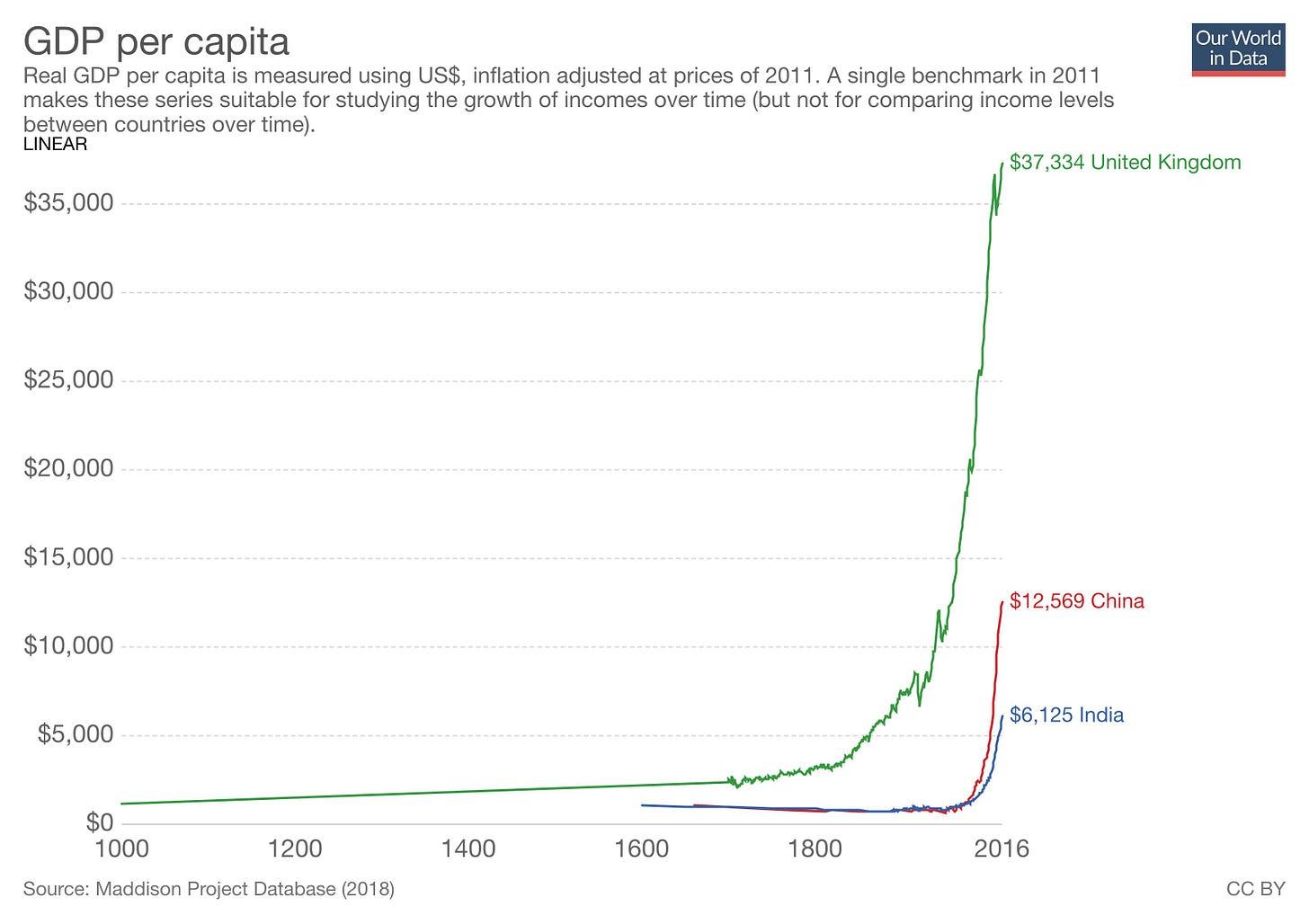

Ironically, though, he was writing at the very last moment of human history when that was plausibly true. Late 18th-century England was in the early steps of the economic takeoff known as the industrial revolution, which would spread to northwestern Europe and North America and then to the rest of Europe and to Asia over the next couple of centuries.

Ours is a world of much more rapid economic growth than any country had ever experienced in Smith’s time, and the fact that industrial revolutions reach different countries at different points in time became by far the biggest source of differences in prosperity. Smith could not explain this, because it literally hadn’t happened when he wrote his book.

The other half of the prize this year went to economic historian Joel Mokyr, who would argue that despite the irony, there is no coincidence here. Smith is a leading figure of the Enlightenment, a cultural trend toward believing that humanity could better itself through the systematic application of reason and empirical data to problems. And that culture of Enlightenment, according to Mokyr, is why the industrial revolution happened.1

But Aghion and Howitt, in the spirit of Enlightenment, try to answer — or at least model — a more specific question: Given that human prosperity depends so much on innovation, what are the nuts-and-bolts economics of how it happens?

Back in the 1950s, economists formalized the Solow-Swan model of long-term economic growth, which provides useful insights on a number of questions, but treats technological progress as external to the model. New ideas are simply assumed to develop, and then the model shows you how this interacts with other features of the economy.

And from the standpoint of many countries, especially smaller ones, changes in the technological environment really are basically random external occurrences. If you look at countries like Poland or the Dominican Republic that have done well over the past thirty years, it’s not necessarily because they’ve become dynamos of innovation. They are successfully importing and adapting to foreign technologies, but the actual pace of change is largely out of their control.

Still, there’s something inherently unsatisfying about exogenous growth models. Innovation is important to growth, and people want to know the circumstances under which it happens.

Part of Schumpeter’s point about creative destruction is that progress has a lot of short-term downsides — it renders existing technologies and processes built around them obsolete, destroying value even while creating new long-term potential. And you should only do that if you’re able to capture the upside.

But in a market of perfect competition with no profits, you can’t capture the upside, so there would be no point of innovating. In his book “Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy,” Schumpeter argues that the lack of perfect competition is not a flaw in the system but in fact necessary to its functioning. He argues that when we search for innovation, “the trail leads not to the doors of those firms that work under conditions of comparatively free competition but precisely to the door of the large concerns … and a shocking suspicion dawns upon us that big business may have had more to do with creating that standard of life than with keeping it down.”

In other words, a dynamic, innovative economy can have a little monopoly power as a treat.

The U-curve of innovation

Schumpeter, along with guys like Hayek and Keynes, is one of several famous writerly economists operating in the mid-20th century. A lot of later economics consists of trying to build formalized mathematical models that express the ideas of the writerly economists in a more math-intensive way. That includes Aghion and Howitt’s 1992 paper “A Model of Growth Through Creative Destruction” and their 2005 update with Nick Bloom, Richard Blundell, and Rachel Griffith as co-authors.

The original paper suggests that an economy could feature a very low level of innovation without any obvious policy problem.

If there is very little R&D spending, you get very little innovation. If there’s a lot of R&D spending, you get more innovation. But the fact that R&D is expected to be high in the future suggests that your current R&D is likely to produce innovations that will be rapidly rendered obsolete and thus not very lucrative. This in turn should push research effort back down.

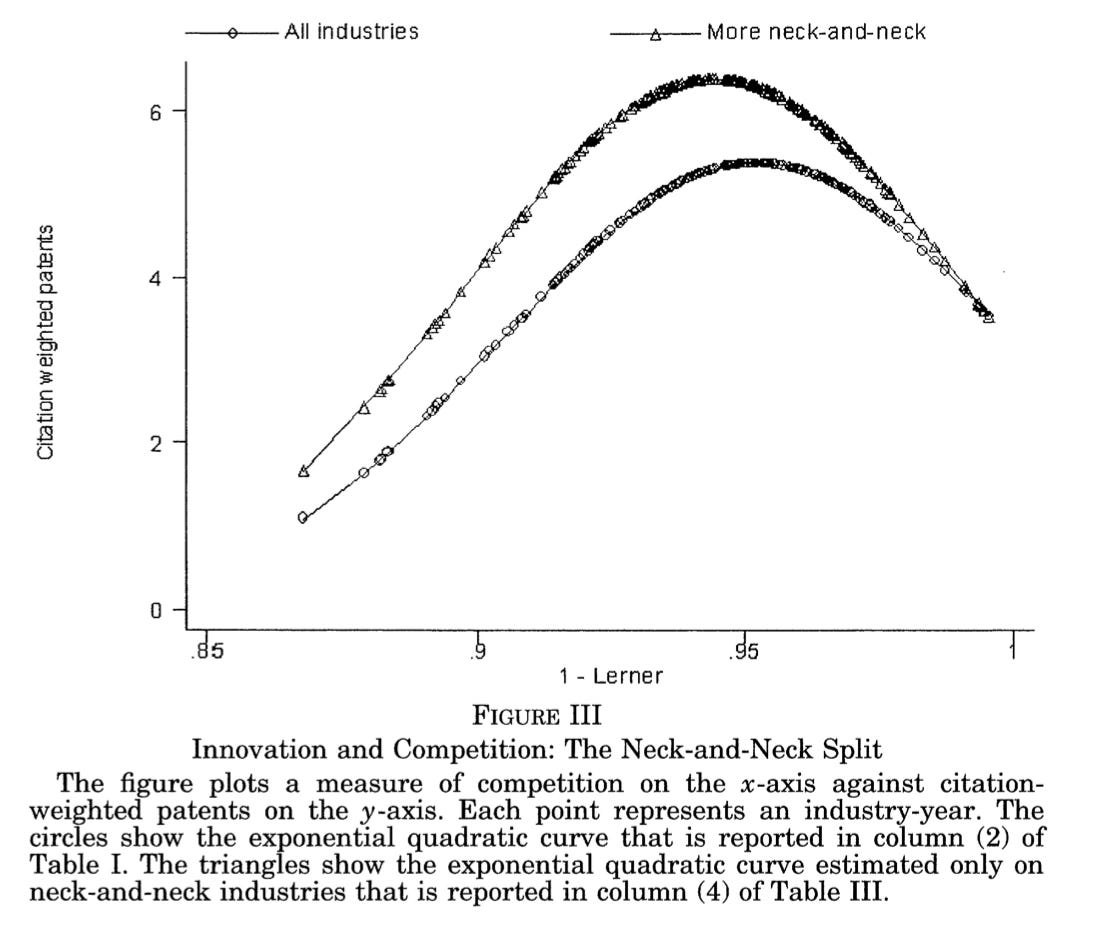

But that’s assuming a lot of competition. In an economy where companies have more market power, they are more able to profit sustainably from their innovations, and thus there may be more reason to maintain a high level of investment in research. On the other hand, a company with a genuinely impregnable monopoly may have no reason to bother innovating at all. In the later paper, they propose an inverted-U relationship between competition and innovation. True monopolization is bad, but they say you get the most patenting from companies that face moderate levels of competition.

They also find that you see more innovation in sectors that feature what they call neck-and-neck competition — sectors “where incumbent firms are operating at similar technological levels.” As you might expect, there are disputes in the literature about whether this empirical finding holds up. Unfortunately, economics gives much less in the way of clear-cut answers to these giant questions about where innovation comes from than it does to Smithian questions about the static allocation of resources.

But their point — that there can be tradeoffs between consumers’ interest in more robust competition and the growth impacts of innovation — seems correct.

We hear about this a lot in the specific case of prescription where, infamously, patents create monopoly rents that allow pharmaceutical companies to sell pills for dramatically more than the cost of manufacturing them. The point of this bar to competition is that by making it lucrative to invent new drugs, you make sure that financial and material resources are invested in drug discovery. Of course, there’s a lot more you could say about pharmaceutical pricing. But I think the headline point that low consumer prices are not the only relevant goal here and we also care about things like the pace at which brand new treatments are developed is clearly right.

Beyond the cost of living

I’m a big believer in political pragmatism and would never in a million years suggest that anyone running for office in the current cycle express any interest in any economic policy topic other than bringing down the cost of living and addressing the affordability crisis in America.

That being said, my takeaway from Aghion and Howitt is that there’s more to life than bringing down the cost of living and addressing the affordability crisis in America.

Thomas Philippon published an interesting book in 2019 titled “The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets.” In it, he observes that between 2000 and 2017, average prices increased by 15 percent more in America than in Europe. He blames this on a relative lack of competition in American product markets compared to European ones. And in a manner that could helpfully heal some factional divides inside the Democratic Party, he finds that this less-competitive situation in the United States is due to both insufficiently vigorous antitrust enforcement and excessive regulatory barriers to entry that the European Union has done more to tear down.

And yet, looking at 21st-century economic history, one might ask how important this actually is.

The United States started the period with higher material living standards than Europe, and the gap has grown since then. Europe has done a better job of managing competition between wireless broadband providers and delivering the same service to customers at a lower price. But the United States has done a better job of being the country where almost all the world’s leading technology companies are based.

I saw Paul Krugman suggest recently that this really just amounts to Silicon Valley being in the United States, not a systematic American advantage. But if you look at PitchBook’s start-up rankings, it’s not just that the Bay Area ranks ahead of London in deal value, so do New York, Los Angeles, and Boston. Then Philadelphia is ahead of Paris. And D.C., Denver, Miami, Austin, Chicago, Seattle, and San Diego all come in ahead of Amsterdam, the third-ranked European city. You can ignore Silicon Valley entirely and the American start-up sector is still dramatically larger than Europe’s.

Understanding why that is, exactly, is complicated, but a different Aghion paper (co-authored with Antonin Bergeaud and John Van Reenen) identifies labor market regulation as a key culprit.

Europe has done more to promote competition on the product market side, bringing prices down. But across a number of dimensions, they make it harder for companies to profit from innovating. As a result, they get less innovation and are poorer.

That’s not to say that competitive markets and low consumer prices are necessarily bad, though they at times could be. But the whole policy focus on that area looks a little myopic when you zoom out. The upward trajectory of human prosperity is achieved primarily through new ideas, new inventions, and creative destruction, not by making existing goods as cheap as possible.

Again, that’s not to say that competition policy is irrelevant or that everyone should be under the thumb of predatory monopolies.

But in the European case, there’s a question of whether their policy reforms have been fundamentally focused on the wrong things. For the United States, I would say it’s more just a reminder that you don’t need to be hyper-paranoid about any instance of a business successfully securing pricing power in the market and making profits. Sectors completely shielded from competition become stagnant. But the lure of at least temporary market power is part of what drives innovation forward — if every business opportunity was immediately competed away, nobody would do anything.

This is an interesting hypothesis, and I’ve really enjoyed everything of Mokyr’s that I’ve read. But I’ve read a number of other really very enjoyable books that also tackle the “why did the industrial revolution happen” question, and unfortunately, they have incompatible theses.

I think Western European labour regulations suck and are the single biggest reason Europe doesn’t have more new tech companies. Source: sit on the board of a few companies that have attempted to expand in Europe with different degrees of success.

I think the example of wireless broadband cuts the other way. US cell service is more expensive and less good and less innovative that in other countries. Instead the broadband companies keep trying to acquire media businesses to seem cooler and mismanaging them.

I think the distinction this points to is between sectors where monopoly occurs due to the structure of the business (like electricity or cell service) and competition requires competition policy and markets where monopoly emerges from competitive markets naturally like search engines, where breaking things up is much less needed.