How Obama (and Trump and Biden) beat Europe

The growing transatlantic prosperity gap

Fifteen years ago, I was pretty bullish on Europe.

It was poorer than the United States, yes, but a lot of that was more vacation time, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. They had a more humane, seemingly more cost-effective health care sector. And with the expansion of the European Union and the forging of deeper economic ties among members, Europe was poised to reap the benefits of a large positive shock that would let them erode some of the advantages the United States enjoyed in terms of economies of scale.

Meanwhile, the United States had what seemed like much worse fiscal policy, running huge budget deficits with a very large chunk of that Bush-era deficit spending going to waste in Iraq and Afghanistan.

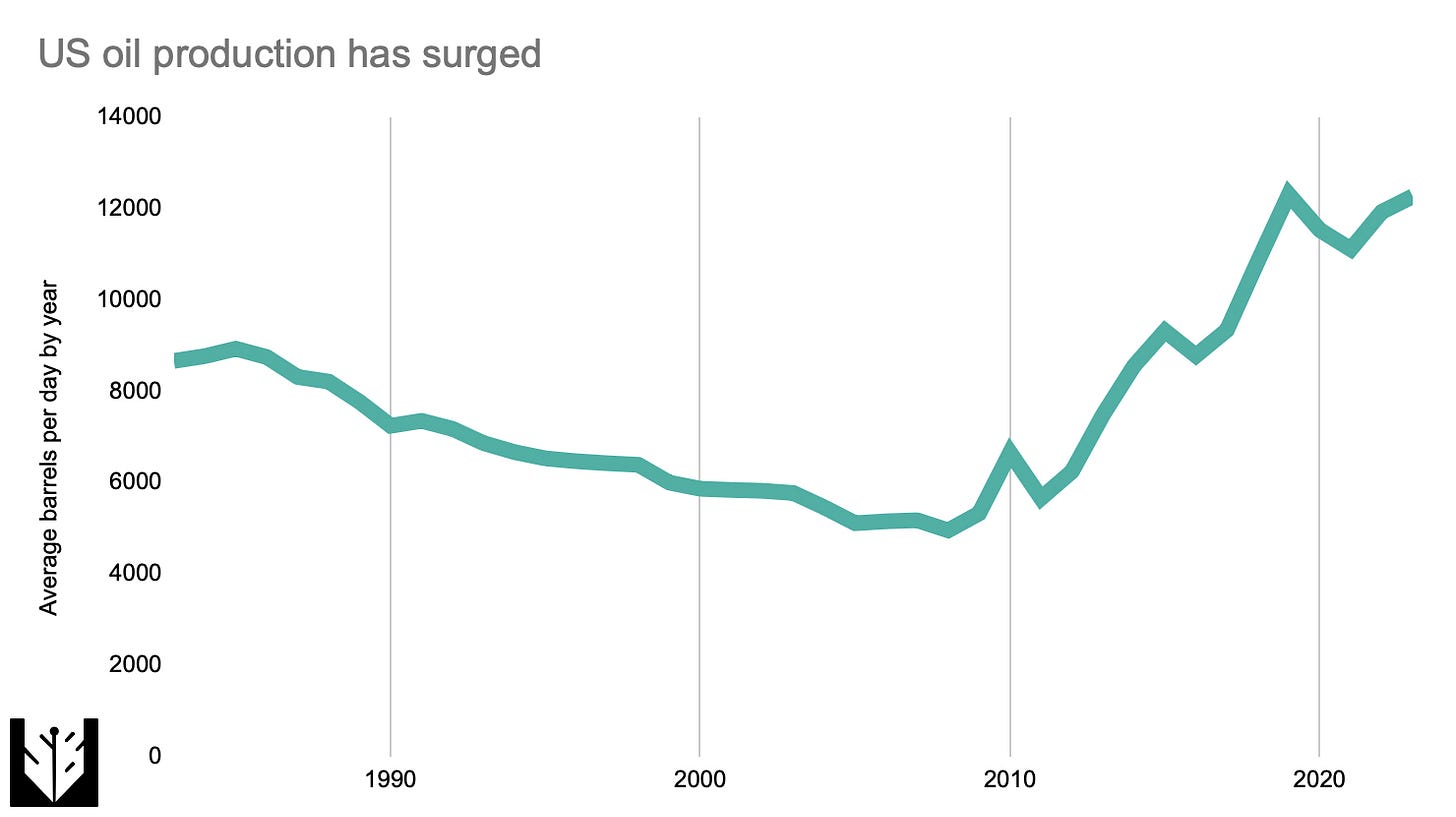

Those wars were linked to another critical weakness in the American political economy — our tremendous appetite for foreign oil. Many Americans had become profligate consumers of oil at a time when the United States was a huge oil-producing country, but our productive capacity had reached its presumed peak in the early ’70s and was thought to be in a state of terminal decline. China and India were growing more rapidly than any rich country possibly could, increasing their own consumption of petroleum in a way that was structurally increasing world prices and structurally worsening America’s terms of trade. This hurt Europe, too, but Europe made much greater strides in energy efficiency back in the 1970s and 1980s, leaving them better positioned to deal with the rise of the rest and the attendant commodity squeeze.

Today, those forecasts don’t look so good. As Gideon Rachman recently wrote in the Financial Times, “in 2008 the EU’s economy was somewhat larger than America’s: $16.2 trillion versus $14.7 trillion. By 2022, the US economy had grown to $25tn, whereas the EU and the UK together had only reached $19.8 trillion.”

Europe is still a very nice place to go on vacation and exceeds America in some important public health outcomes, but the diverging economic fates are interesting and deserve some explanation. And I think a lot of what you hear about this doesn’t make sense because it cites transatlantic differences that have been in place forever — Europe had higher taxes and stronger labor unions than the United States 15 or 30 or 45 years ago. But for a while, they were catching up to us, whereas now they’re falling back. The question is what changed since George W. Bush left office.

Macroeconomic management

American macroeconomic management during the Obama years was bad, in the sense that fiscal and monetary policy left us understimulated with millions of person-years worth of unnecessary unemployment.

But we did much better than Europe, which mired itself in a disastrous situation. Germany and some other northern European countries’ economies held up better than the economies of Spain, Italy, Greece, and Portugal, but because all of these countries were bound together by the Euro, the harder-hit countries couldn’t adopt stimulative policies of their own accord. This created a sense in the countries with stronger economies that they were being asked to provide “bailouts” for their neighbors. And a direct fiscal transfer from Germany to Spain is certainly one way macroeconomic policy could have been done.

At the time, though, interest rates were incredibly low.

EU-wide bonds could have financed larger deficits for all countries simultaneously, allowing Spain and Italy to do less austerity while Germany gave itself a VAT cut. Or they could have accelerated the construction of its high-speed rail network. They could have built up their military capacities. Or some combination of the three. The point is that while, obviously, the straightforward “give a bunch of money to the people who need it” solution faced daunting obstacles, creative political leaders could have come up with win-win ideas that left everyone better off instead of descending into moralizing and finger-pointing.

This was exacerbated by the attitude of the European Central Bank, which responded to the lack of fiscal stimulus by erring on the side of doing too little monetary stimulus. The view from Frankfurt often seemed to be that the ECB staff knew better than the voters of Italy, Spain, and Greece how to conduct microeconomic policy, so they should punish southern Europe with high unemployment until southern European governments made policy changes they approved of.

The fracking revolution

As America’s more deficit-friendly politics shifted from a weakness to a strength, the transatlantic energy situation also transformed. The rise of Chinese and Indian demand did put upward pressure on commodity prices. And given Americans’ very high per-capita oil consumption, that did worsen our global terms of trade. But it also created large financial incentives for innovation in oil extraction, and America came through with big strides in hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling.

Europe responded to these developments largely by banning fracking, while Obama encouraged it. There was no ban during his administration, and as he explained in his 2014 State of the Union address, the huge increase in natural gas production that came thanks to fracking was part of his decarbonization strategy:

Now, one of the biggest factors in bringing more jobs back is our commitment to American energy. The all-of-the-above energy strategy I announced a few years ago is working, and today, America is closer to energy independence than we’ve been in decades.

One of the reasons why is natural gas — if extracted safely, it’s the bridge fuel that can power our economy with less of the carbon pollution that causes climate change. Businesses plan to invest almost $100 billion in new factories that use natural gas. I’ll cut red tape to help states get those factories built, and this Congress can help by putting people to work building fueling stations that shift more cars and trucks from foreign oil to American natural gas. My administration will keep working with the industry to sustain production and job growth while strengthening protection of our air, our water, and our communities. And while we’re at it, I’ll use my authority to protect more of our pristine federal lands for future generations.

This is one of the most misunderstood developments of our time. Republicans like to greatly exaggerate the extent to which Democrats oppose domestic fossil fuel development, while Democrats often seem embarrassed to point out that Republicans are lying — Obama’s speech was a notable exception.

And indeed, at the beginning of his term, Biden seemed to flirt with the anti-oil policy approach. But he abandoned that swiftly, oil is now pumping at a record pace, and his administration is adopting smart, creative approaches to the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and using issues like the global price cap on Russian crude to maximize America’s strategic and economic interests.

This notably doesn’t even come at the expense of decarbonization. The existence of cheap natural gas as backup lets you take advantage of cheap renewables without worrying too much about harder problems like batteries. Powering a factory with gas causes fewer emissions than running it off coal. Powering a car using a mix of gas and renewables generates radically fewer emissions than running it off gasoline. There is obviously a margin at which this ceases to be true, but it’s not the margin we are currently operating on.

Europe, meanwhile, didn’t actually quit fossil fuels by banning fracking. It just imported the gas from Russia instead.

Silicon Valley forever

The last big American victory is a factor you could already see in place by 2008.

A person transported back in time 15 years would have no trouble seeing that the United States was the world leader in computer software. Google was the world’s leading search engine. It shared email provider honors with Microsoft, the biggest maker of business software. Apple’s hardware/software vertical integration created uniquely desirable high-end devices. We had venture capital firms that were comfortable investing in high-risk startups. And we had a deep labor pool — engineers knew that if the startup they were working for went bust, they could find new jobs elsewhere, and founders knew that if their startup experienced rapid growth, they could find more people to hire.

These broad facts have just become much, much more important as the relative significance of this economic sector has soared. It could have been the case that as computer stuff became more important, its production also became more widespread. And certainly the industry is more globalized in significant ways. But a lot of that globalization happens inside the United States of America. Satya Nadella was born in India, came here on student visas, got a green card, actually gave up the green card and switched to an H-1B at one point so he could bring his fiancée over, and became the CEO of Microsoft. Sundar Pichai likewise came from India on student visas, switched to an H-1B to get a job at McKinsey, and has been here ever since rising to run Google.

Daniel Ek’s Spotify is the one really big European tech startup, but the number two European-founded startup is Stripe — only the Collison brothers live in California and the company is headquartered in South San Francisco.

America keeps flirting with killing the golden goose with over-the-top populist rhetoric and immigration restrictions. The Trump administration kept trying to leverage very real flaws in H-1B as a pretext to kill the program rather than reform it, while Democrats risk letting asylum chaos drag down legal migration. But so far, we have kept the high-tech flywheel spinning to our advantage.

The roots of success

The other thing that happened in this period, of course, is that with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, the American health care system got a lot better. The uninsured rate has fallen. The cost curve bent. We did not solve the problem of health care provision in the United States, and our system still lags behind Germany and France in key ways. But we actually did make progress on one of the key areas of European advantage, while I don’t think the Europeans have gained ground on us in any key way.

So why?

On the most superficial level, I think Barack Obama was just a really good president who made important and under-appreciated progressive changes while also forcing progressives to live with some important changes they were resistant to.

But I don’t think that’s the only reason. I remember going to Germany in, I think, 2009 with a small group of American journalists. We were in some eastern city in a van driving down a narrow alley when we had to stop because there was a Smart Car incorrectly parked in the alley, leaving us with no space to pass. Our van driver couldn’t back out and he couldn’t go forward, so he said we’d just have to wait. A middle-aged American woman in the group said that was absurd, and that yours truly and a few other younger guys on the trip could just get out, pick up the Smart Car, and move it. The driver said, “no, no, no, it’s not possible.” But she insisted that the four of us get out and move the car, and so we did, kind of like in the Mentos ad.

We got back in the van, and she said to the driver very definitively, “that’s the American spirit!”

And I think there’s something to that. America’s public culture really does valorize pragmatic problem-solving. A lot of what’s most frustrating about American public policy comes in areas like mass transit where we could improve by simply copying the best practices that already exist in Europe and Asia but insist on trying to make up new ideas (Uber Pool!) instead. But we are generally less rigid and more adaptable.

The deeper reason, though, is that Europe has kind of killed off politics. So much power now rests at the EU level, but the EU doesn’t conduct a recognizable form of democratic politics. Voting for the European Parliament has what David Schleicher terms a “second-order” pattern, where Spanish voters will cast their votes in the European Parliament elections as a way of voicing approval or disapproval for the performance of the prime minister in Madrid. The same is true in Italy, Poland, and so forth.

Regardless of the actual election results, the Parliament is always controlled by a grand coalition with a senior center-right bloc and a junior social democratic bloc. The European Commission — the EU’s version of a cabinet — guarantees each country one Commission slot, so the actual composition of the Commission is a mess based on who controls which country at any given time. And the prime ministers of even small and mid-sized EU countries don’t see moving up to Brussels as a promotion the way American governors become senators or cabinet secretaries run for president.

It’s not exactly an “undemocratic” system, but it’s very depoliticized. You don’t have clear partisan coalitions or a real policy debate, you don’t have incumbents worrying about reelection or ambitious opposition figures looking to gain power. And I think this has consistently undermined Europe’s ability to think clearly about tradeoffs and strike win-win bargains.

The next pragmatic challenge

The important exception to this story of American triumphalism is that the United States had worse life expectancy than Europe 15 years ago and the gap has grown since then.

Or to put it another way, we used to be comparable to the leading European countries like Italy and Germany, and we’re now comparable to a country like Poland which is poor by European standards.

This isn’t a post on life expectancy, but I do want to say that I don’t believe there’s a genuine tradeoff here. It’s not as if America’s much higher level of homicides, car crashes, and drug overdoses is either a cause or a consequence of American prosperity. On the contrary, we would be even richer if we solved those problems. The link between America’s higher rate of obesity and obesity-related ailments and prosperity is tougher to figure out — I do think it’s plausible that we are fatter than Italians primarily because we are richer.

But in the spirit of pragmatism and problem-solving, this troubling American tendency to die young deserves to be the center of much more of our policy debate. We are doing well in many areas, but avoiding untimely death is something most people would like, and our material prosperity is not delivering.

I think the fact that the EU has very aggressive antitrust and pro-privacy regulations and the fact that basically the only innovation to come from the EU's tech sector in recent years is making us click "Accept Cookies" are not unrelated.

Writing as an American from Sweden, this essay strikes me as superficial, unsubstantiated, and just incorrect on its own terms.

Firstly, it misinterprets the reasons why the United States is uniquely successful in certain key areas (IT, domestic energy) as policy choices rather than just "not screwing up a lucky break." And it points the finger at European for dropping the ball when a lot of what they "did wrong" was just an issue of structural constraints and no-win dilemmas. And granting "the win" to Obama and Biden is granting them too much agency in this process. If anything, the policy choices that had more bearing on those successes in both Silicon Valley and Houston go back WAY further, to the first half of the 20th Century. And that subject deserves a closer examination from you here because Americans tend to think that tech, especially, is some new thing dreamt up by Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, instead of an industry that saw its inception prior to WWII (and scaled out largely because of the war).

But, whatever the origin story, the salient factor for American Big Tech's dominance today has less to do with entrepreneurial genius, government policy, or anything purposeful like that. It's just a matter of size: the United States has Silicon Valley because it, alone, is the world's only rich, single market of sufficient size for an industry that rewards network effects and clustering. Europe (or the EU/EEA) is a single market on paper, but it has structural barriers that create friction for developing scale in financing, talent pipelines, and go-to-market. I can tell you all sorts of anecdotal stories about this as a founder and employee for both American and European tech companies of every size, but just imagine what it's like for a London tech office (still the dominant European tech city even after Brexit) to recruit tech workers from even neighboring France (impossible to get working visas, language barriers, Brexit-driven administrative nightmares, etc.) and compare that to the pool of 330 million Americans that any US tech employer can draw to Silicon Valley or elsewhere without any of that. Germany managed to make a tech giant in SAP right around the time that Microsoft was incubating, but SAP is never going to be able to draw upon a huge, captive domestic market like its tech peers Microsoft, Oracle, or Google. Since IT hardware is simpler to export, you have a different story for Europe there: chipmaker ASML is certainly doing quite well for itself coming out of tiny Netherlands.

China and India are the only two other continent-sized countries with huge population that could scale like this, but both of them are still poor on a per-capita basis, retain significant internal barriers for business even within their own countries, and are extremely difficult to recruit foreign talent into. China has its Alibaba and India its Infosys, but they're likely never going to surpass their American competitors as long as the United States is still the only really big, really rich country.

Energy is an even more obvious area where the United States is just plain lucky. The oil boom started in Pennsylvania and America was the world's largest exporter until the 1970s and now again today. Europe (ex. Russia) basically doesn't have fossil fuels. Norway's production is enough to make Norwegians rich, but nowhere near enough to even feed Scandinavian energy demand, much less the entire EU's. Yes, some European countries could have joined the fracking boom (and you neglected to mention how some like Poland, Romania, and Denmark actually did), but that wouldn't have moved the needle significantly. Europe just doesn't have this option on the table, whatever their qualms. Again, structural factors matter: Sweden transitioned away from oil in the 1970s not for environmental reasons, but purely for pragmatic ones after the various oil crises of the decade threatened to derail their heavily industrialized economy that lacked domestic fossil fuel access. The Swedes quickly built out hydropower and nuclear power at a fast clip because that's what Sweden could do. For France, lacking hydropower, their answer was the world's biggest concentration of nuclear power plants. Germany could have chosen to take after France, but they instead fell back on that Ol' Ruhr Valley Reliable: coal. A fateful decision that continues to haunt them. The UK and Denmark have now been opting for wind because that's what they have a lot of, just like Spain and Italy are going big on solar, and Norway and Sweden continue to enjoy their geographic gift of abundant hydropower. Iceland, famously, leverages its geothermal resources to not only be largely energy-independent, but also to dominate the aluminum smelting market with some of the cheapest electricity and industrial heat in the world.

Aside from Germany and their peculiar and paradoxical anti-nuke Green politics and soft-on-Russia Ostpolitik, I don't see a lot of evidence of Europeans lacking pragmatism or making stupid decisions on energy. Yes, I absolutely would have loved to see the EU and ECB itself take a bigger role in facilitating the green transition and maybe even resolving some of the cost and scaling issues of nuclear power with some subsidies, but that's the weakness of a contested federal system, isn't it? We have had the same issue in the US for decades until "Bidenomics" (which, as you have written about, isn't an unmitigated success yet). Mostly I just see Europeans making pretty good choices within some major structural constraints.

But that's not a story that Americans like to hear. Europe is a dark mirror for Americans, either a Utopia or a Dystopia! A shining exemplar or a miserable failure! Maybe both...? But couldn't it be true that Europe isn't perfect but is just... doing fine? And that it's not just a "good place to vacation," but also a great place to live?

And that Europe is arguably even better for the median European than the United States is for the median American, by most objective standards? (Glove thrown!)

You mention (and wave off) the embarrassing issues of the Great American Life Expectancy Deficit, where Europe is clearly wiping the floor with the United States. But you could have mentioned all sorts of other quality-of-life factors, too, even the ones that Americans pride themselves on. We all know that Europeans have it made when it comes to vacation time, paternity leave, healthcare access, public transit, unionization and working conditions, walkable cities, delicious food, non-toxic environment, and joie de vivre-type stuff like that. But what about all the materialist pleasures that Americans ostensibly value? The country where you can get hella rich, even if it kills you, bro! Though Americans do make higher salaries and pay lower taxes, they actually have a much lower household savings rate than Europeans. Which is pretty obvious when you account for all the things that those (slightly) higher salaries are supposed to pay for on the (crazy inflated) private market: a (big, expensive) car for every adult, five-figures in daycare for every child under age 5, thousands out-of-pocket for healthcare (with "good" insurance!), ruinous costs for eldercare for all those Boomers, etc. Stuff that is covered in the (slightly higher) taxes for most Europeans. Also, we tend to assume that workaholic Americans are always working, but it turns out that they're not: the US also has much a lower labor participation rate than "lazy" Europe. A shocking and under-discussed issue that is related to the sorry state of our safety net and healthcare "system." Americans also don't own their homes at the same rate as Europeans, and their experience as renters is far worse than their European peers. They have higher poverty, too, both in relative and absolute terms. So, it turns out that we Americans are not actually so rich, in practice, but we will certainly die tryin!

That type of stuff might not register to well-compensated Substack columnists who experience Europe as tourists, but it is exactly the kind of stuff you should be interrogating when making statements about how the US "beat Europe." This isn't to say that the US is a dystopia or miserable failure, either. Both places house among the luckiest humans alive or dead, living a lifestyle unimaginably abundant for most people who have ever lived. But, in terms of making that abundant life abundant for a wider swath of the population than only the top 20%, Europe still has a lot to teach Americans.