The AI boom is propping up the whole economy

It’s a fragile basis for growth, whether or not it’s a “bubble.”

In case you missed it, I wanted to share our weekly housing news write-up from Writing Fellow Halina. If you enjoy this one, we post the latest in housing every Wednesday and share shorter original pieces every Monday and Friday for paid subscribers. If you’re already a paid subscriber and would prefer not to receive our evening pieces (or would prefer to only receive those), here’s how to opt out.

A “data center” is basically a big building full of computers. Until recently, you probably didn’t hear very much about data centers, because even though computers are an important part of daily life, building large structures full of computer equipment is not a particularly large share of the economy. And yet it’s in the news a lot these days, because this year the change in spending on data center construction is large relative to the total change in economy-wide spending.

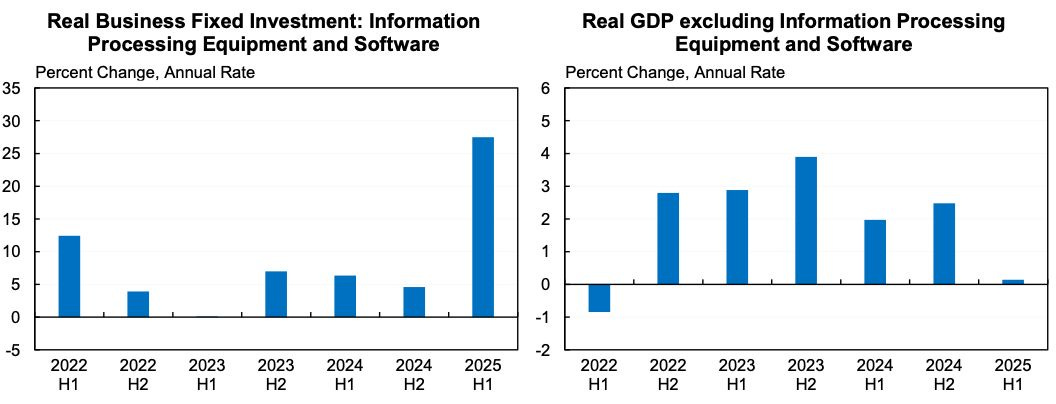

In other words, as Jason Furman recently noted, the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s category for investment in information processing equipment and software accounts for over 90 percent of economic growth in the first half of 2025.

This doesn’t mean that without the data center boom, we would have experienced zero economic growth. Much of the financial capital and real resources that are currently going into data centers would have been deployed by some other sector absent the boom. But in terms of the actual American economy, the AI boom is the whole story.

The story of how the stock market learned to love the Trump administration is not without nuance, but it is actually overwhelmingly the case that AI-related stocks dominate the market, and the administration has been quite solicitous of AI-specific interests — including with tariff exemptions.

But not only is there a lot of money being made off the AI boom, there’s a lot of obvious boom-market behavior. AI start-ups are getting funding with minimal scrutiny, and the AI construction boom increasingly features unorthodox financial arrangements. There’s nothing wrong per se with a little innovation in how deals are structured. But it’s also true that, throughout history, we’ve seen investment booms go beyond a sustainable level, fueled by creative financing that obscures weak fundamentals. I’m hearing more and more questions about an “AI bubble,” and I even see people confidently proclaiming that one exists.

That’s not a crazy hypothesis, for reasons that we’ll explore below. But I do also want to caution against motivated reasoning.

A lot of people are both deeply alarmed by Donald Trump and also deeply resistant to Slow Boring-style calls for significant steps to expand the Democratic Party to include those with more conservative views on some issues.

Democrats’ best chance to defeat Trump through pure acts of stand-your-ground resistance is if the economy experiences a massive setback, just as Barack Obama won a landslide victory in 2008 with a platform that was no more moderate than John Kerry’s (though significantly more moderate than Hillary Clinton’s, Joe Biden’s, or Kamala Harris’s) simply by pairing charisma with very bad fundamentals for Republicans.

So telling yourself that the economy is on the verge of collapse offers a convenient way to avert political tradeoffs. Similarly, the data center boom is raising electricity demand in ways that are problematic for environmental groups’ net zero timelines. But blocking data center construction would seem to have major economic costs that people will probably not want to bear. However, if all the investment is just a crazed speculative bubble that will end in tears, there is no economic cost to blocking the buildout.

Those are certainly reasons to want to believe there’s an AI bubble. But they’re not good reasons to believe it.

Some good reasons to believe there’s an AI bubble

The poster child for the bubble thesis is actually a bit removed from the issue of data centers.

Mira Murati was OpenAI’s chief technology officer, but left the company in the wake of the abortive coup against Sam Altman. She then put together a small but impressive team of people from leading AI labs and successfully raised $2 billion in venture capital (at a $10 billion valuation) for her new start-up, Thinking Machines, which by most accounts had no demo product or even really a clear pitch.

It’s common — cliché even — in V.C. spaces to say that you’re really backing a team, not a specific idea.

I’ve lived that. When we were pitching the idea that became Vox, people absolutely did listen to the details of our pitch, and they asked questions about it and had varying degrees of enthusiasm in response to it. But fundamentally, the people who were interested in the pitch were interested in Ezra Klein and Melissa Bell and Matt Yglesias.

And that was not a crazy calculation. A lot of our initial big ideas frankly didn’t work out, many of them quite quickly and obviously after we started. But we’d hired a fantastic initial team, and when you have smart people with good values and good work ethic, you drop ideas that don’t work and shift to other ideas that are better. Some of our biggest successes ended up coming in places like the video program, where we had virtually no ideas in our pitch, but we hired two absolute geniuses and they hired more amazing people.1

Still, the other thing that really helped us get off the ground is that, at the time, investors were enthusiastic about ad-supported digital media properties. There was a thesis (wrong, as it turned out) that you could make a lot of money in that business. So a ton of digital media start-ups got funded, and many of them failed. But what really made the idea a dud is that even the ones that didn’t fail — like Vox — did not turn into huge successes that made tons of money for the founders and investors.

That’s where it gets hard to judge these things.

Investing in start-ups is inherently uncertain, and the business model depends less on having a very high batting average than on the idea that home runs will be extremely lucrative.

So when a given sector becomes fashionable, the bar for which pitches get funded is lower. We pitched Vox at a time when the bar for digital media pitches was relatively low. If we’d gone out with that five years earlier or five years later, nobody would have put money into it. With AI right now, the bar is currently very low, and it’s obvious that a lot of the projects getting funded aren’t going to work out. But this doesn’t actually speak to the merits of the thesis that this is a promising field. The thesis lives or dies primarily on the question of how big the hits will be. And if I could tell you that, I wouldn’t be writing a subscription newsletter for a living.

Weird financial shenanigans

The most eyebrow-raising aspect of the whole thing, though, is the spate of unorthodox financial arrangements that have been announced this fall.

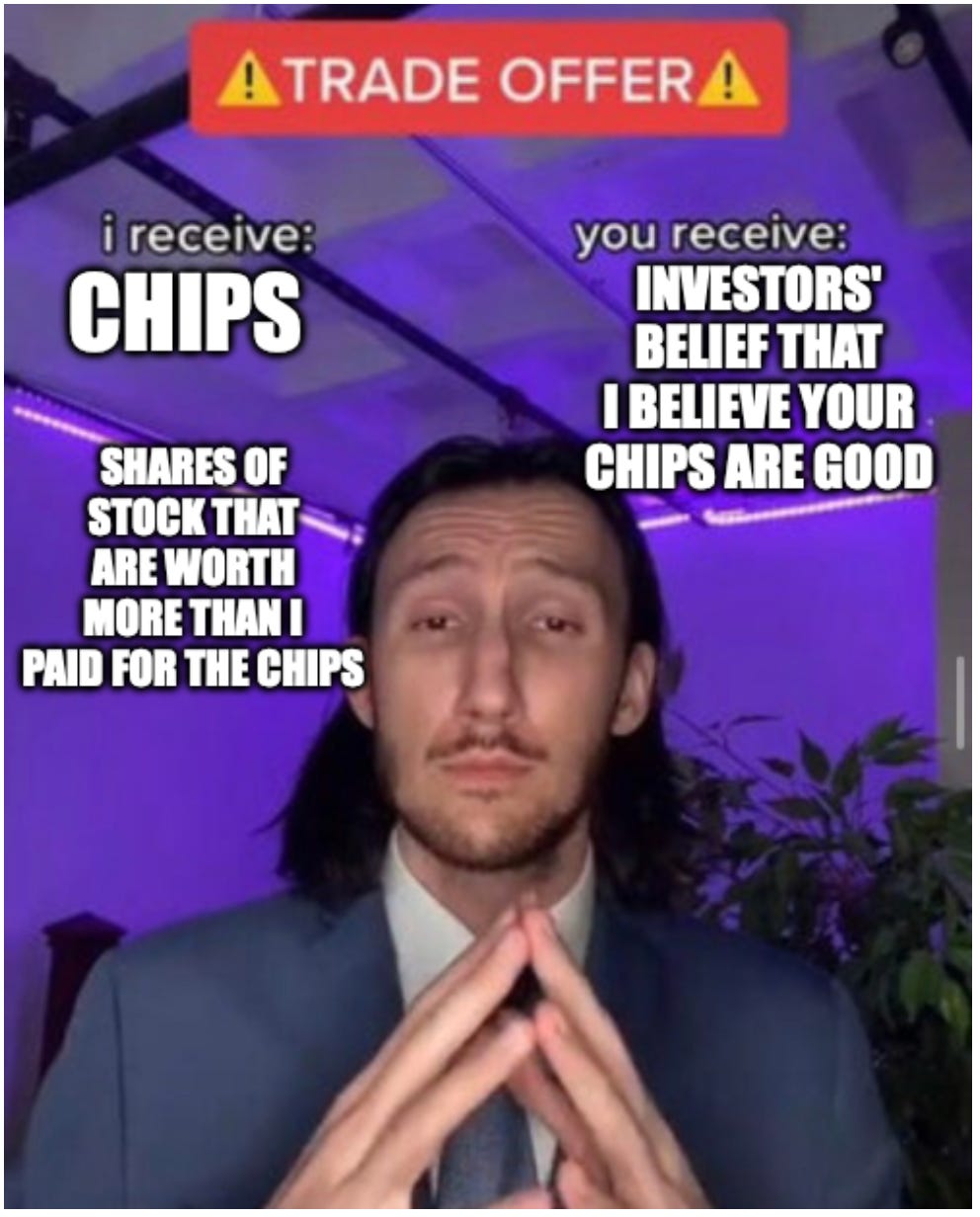

Consider last week’s deal between OpenAI and AMD.

Cutting-edge AI work has thus far mostly relied on Nvidia high-end chips. AI labs, naturally, don’t want all the financial returns to this sector to accrue to their chip supplier. So, OpenAI decided that they were going to buy a bunch of chips from a competing company, AMD, that’s been a bit left behind in the AI race.

The announcement of the deal caused AMD’s stock to go up a lot, in part because the deal should make the company a lot of money. But also because most people aren’t technical experts in training AI models or powering AI inference or in GPU design, but are aware that Sam Altman and his team have an incredible amount of technical expertise in this field. If OpenAI says that AMD chips are useful for the AI infrastructure buildout, that’s a huge vote of confidence that conveys broader information about AMD’s ability to make money off of AI by selling to many companies.

Where it gets really interesting is that OpenAI foresaw that announcing the deal would cause AMD’s stock to soar. So the terms of the deal included warrants for OpenAI to get AMD shares if the price of AMD stock soared. The upshot of this is that, yes, OpenAI is in a sense getting the chips it agreed to purchase for free — the profits on the equity investment in AMD exceed the cash value of the chips purchase. But AMD shareholders also benefit from giving OpenAI the chips, because despite the dilution of their shares, the price increase still leaves them better off.

Each step in this chain makes perfect sense but, as Matt Levine says, it’s also the kind of thing where OpenAI’s dealmaking is so impressive, they could be tempted to spend all their time on deals rather than on building AI.

Or in other words, while I have absolutely no reason to believe that this transaction is anything other than completely above-board, you certainly could take advantage of the basic market dynamics in play here to run a scam.

We’re also seeing deals that go in the opposite direction. Nvidia’s stock has been flying high on the assumption that the company will sell more and more high-margin chips to AI companies in the future. And AI companies certainly do seem to want to buy a lot of chips. But those chips are expensive, which means the AI companies need to raise money to be able to buy them — Nvidia’s future depends on people investing in AI companies who buy Nvidia’s products. So in a recent deal, Nvidia cut out the middleman and made a large investment in xAI, and xAI is using the money to buy Nvidia chips.

The circularity here doesn’t necessarily mean that anything is wrong. In some sense, the whole economy is just money moving in circles. That’s why expansionary monetary policy can help revive a depressed economy — your expenses are someone else’s income, so simply putting more money into circulation can generate real economic activity if there are idle resources or workers to mobilize. But when you get a very small circle rather than a big series of arm’s length transactions, the potential for shenanigans increases.

On the other hand

In a true bubble — like baseball cards when I was a kid or Beanie Babies shortly afterwards — people are buying assets purely on the basis of the belief that they’ll be able to unload the asset to someone else at a later date.

Collector’s items like the aforementioned baseball cards are particularly prone to this dynamic since, by definition, there’s no stream of revenue associated with owning a Ken Griffey Jr. record card. Of course, just because something doesn’t generate a revenue stream doesn’t mean its value is fake. If you have a bunch of Picassos lying around your house, those are assets with very real value. But there’s still nothing like dividends or rents associated with the asset the way there are with shares of stock or homes, so there’s a lot of opportunity for pure speculation to run rampant.

But it seems to me that if you think about the dot-com stock boom or house-flipping in the mid-aughts, it was incredibly common to believe that you could always offload the asset to some other sucker. There’s a reason that bucket shop scams proliferated in the 1990s — very unsophisticated people were buying stocks on the assumption that stocks would always go up, which meant they weren’t scrutinizing specific pitches carefully.

There are often echoes of that behavior in cryptocurrency markets, and we also saw a lot of it when people bored at home during the pandemic got really into “meme stocks.”

And what I will say on behalf of the AI boom is that I’m pretty sure it’s not a bubble in that particular sense.

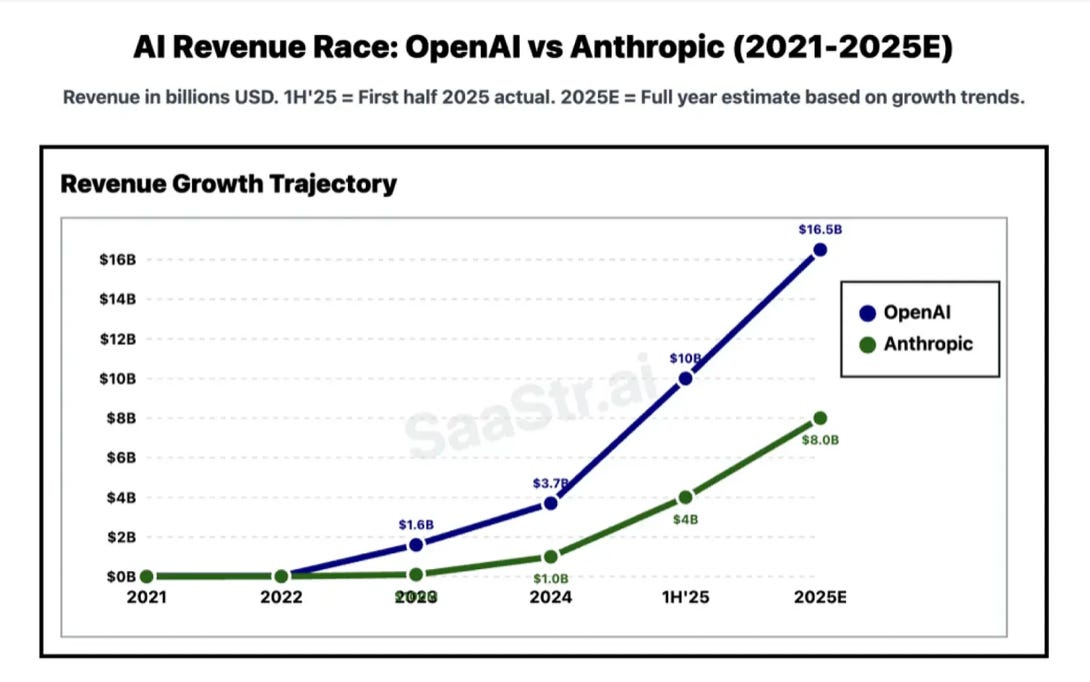

The leading AI labs are genuinely seeing rapid revenue growth. I don’t think “the trajectory of model capabilities improvement and associated revenue will continue on its current path indefinitely” is the most sophisticated investment thesis in the world. But it’s also not unmoored from reality. It’s a plausible but possibly wrong guess about the future state of the world — i.e., a pretty normal investment hypothesis.

I also think that some critics are confusing these companies’ thirst for new capital with the “we lose money on every sale but make it up in volume” nonsense of dot-com-era companies like Kozmo. What’s happening here is that the financial return on any given L.L.M. is pretty good, but each company is continually investing large amounts of money in training the next model on the expectation that it, like its predecessor, will be lucrative.

Does that mean all’s well? Of course not! This could break down in a number of ways:

The hypothesis of continued upward progress in model capability — “scaling laws” that dictate that applying more data and more computing power will predictably generate increasingly powerful models — might be wrong and you could hit a wall.

The frontier companies might lack a meaningful “moat” such that competition renders cutting-edge models actually not that lucrative, no matter how capable they are.

Increasingly capable models might do something harmful that destroys rather than creates economic value. The Entity from the “Mission Impossible” movies was surely bad for stock prices, despite its impressive technical abilities.

If it turns out that some of these closed loop deals between the big companies are scammy, that could create a huge crisis of confidence, even if the underlying technology and finances are fine, which would become a kind of self-fulfilling anti-bubble.

I would not be shocked if some huge stock-market crash is around the corner, but I’m also not betting that it is. As a prognosticator, I take the bubble possibilities seriously, but I take the problem of motivated reasoning equally seriously. I’m much more knowledgeable about politics than I am about finance, and I can tell you that many of Democrats’ internal conflicts feel easier to resolve if they assume something like “Not only is the Orange Man bad, but he’s also bad at his job and his effort to prop up the economy by coddling the AI sector will end in tears.”

I think that’s more or less what Bharat Ramamurti is saying here about why I’m wrong, that Democrats don’t really need to waste much time thinking about ideology and public opinion — they really just need to hash out some forward-thinking policy ideas they can implement when power falls into their laps. I don’t think anyone is per se rooting for a recession or an economic collapse, but convincing yourself that one is coming is a soothing alternative to thinking through the question of how to win in 2028 if unemployment stays low and growth remains robust.

My take on this is that you shouldn’t take financial advice from your favorite political blogger, but also that a political movement shouldn’t take its strategic direction from their hope that the economy is an unsustainable house of cards.

It might be, in which case people in 2029 will have fun poking fun at all my circa-2025 hand-wringing. But the nice thing about financial markets is that the people investing in them have very strong incentives to at least try to avoid wishful thinking and motivated reasoning and instead focus on cold hard cash. Those people absolutely get things wrong sometimes, but they’re right more often than not. And it’s dangerous to assume they’re wrong at just the moment it would be most convenient for you.

I’m excited to see what Joe Posner does next, Joss Fong’s “Howtown” is great, and you can see other Vox video alumni like Johnny Harris and Cleo Abram doing really cool things.

During 2024 the Discourse repeatedly centered on the vibecession, despite the fact that while the American economy of 2024 had persistent higher than target CPI, it also had genuinely widespread growth across sectors and wage gains across income brackets. If anything, wage gains were strongest in the lower brackets, as income inequality was declining.

Those who defended the idea that a recession was happening despite the indicators was that the indicators were bullshit and people were suffering in real life.

I can't help but think that line of reasoning is much more appropriate now than it was then given how concentrated economic growth is in a narrow sector. Not only that, labor and wage indicators are genuinely flat/hinting at trending in the wrong direction. It's clear to me that the AI boom is propping up the top line while the rest of the economy is slowing, as you call out here.

It's just maddening how Trump has this Defying Gravity (my five year old is on a Wicked kick) quality to him, where nothing quite bad enough to penetrate the daily experience of the median American seems to happen while he's around. Pandemics are a weird case where both it's tough to blame someone for them AND as Lindyman argues, society memory holes the experience. I don't want mass suffering, but goddammit I want something to happen that is absolutely attributable to the mad king and everyone knows it.

The one way the AI boom goes bust that you didn't mention: companies realize that the productivity growth they're paying for (through staff reductions/efficiency gains/something else) doesn't approach the amount of money they're spending, and start balking. Right now a lot of the AI attitudes I'm seeing in business center around "we have to do this because our competitors are doing this and we can't be left behind." But you're starting to hear more public grumblings that the emperor has no clothes.