Overtreatment in American health care is a problem

An entrepreneurial, market-oriented system has some downsides.

One of my tweets last week was, unlike most of my tweets, generally popular and well received by progressives. It made the point that one of the structural features of the American health care system is that it’s a basic consumer business, which means giving people medicine that they don’t really need can be very lucrative. Apparel companies want to sell you lots of clothing; American doctors and pharmaceutical companies want to sell you lots of treatment.

To the extent that I got pushback from the left, it was from people questioning whether the innovation is real (also here and here) or saying that innovation is all publicly funded anyway.

I don’t think that’s correct. America’s lack of price controls means that companies have a strong incentive to deliver new treatments here first. And the fat margins they can achieve in the U.S. market clearly drive more investment in treatments than in a more typical system. Reformers often say we could compensate with other pro-innovation policy ideas, and I totally buy that — we could. But if we just cut out the money, there really would be less innovation.

And America’s biomedical innovation is genuinely impressive. One of the mRNA vaccines against Covid-19 was developed by an American company and the other was a joint U.S.-German effort. Paxlovid, a highly effective and underutilized Covid-19 treatment, also comes from an American company. If a rich person in a poor country decides to fly somewhere to get some very expensive health care, the destination is typically the U.S. Our health care system has a lot of failings in terms of access for the poor, annoying bureaucracy, and creating financial insecurity for people with chronic ailments. It’s also pretty obvious that health care is not actually the primary factor in population-level health, and that Americans suffer from unusually high rates of obesity, lethal violence, and car wrecks.

That innovation is valuable, and any reforms should preserve that value. This is one reason I’m very interested in finding ways to make it cheaper and faster to do clinical research.

But the overtreatment issue is real. And as economist Dean Baker says, that extends to treatments that don't work at all or are even harmful.

Overprescription of opioids has caused a huge problem

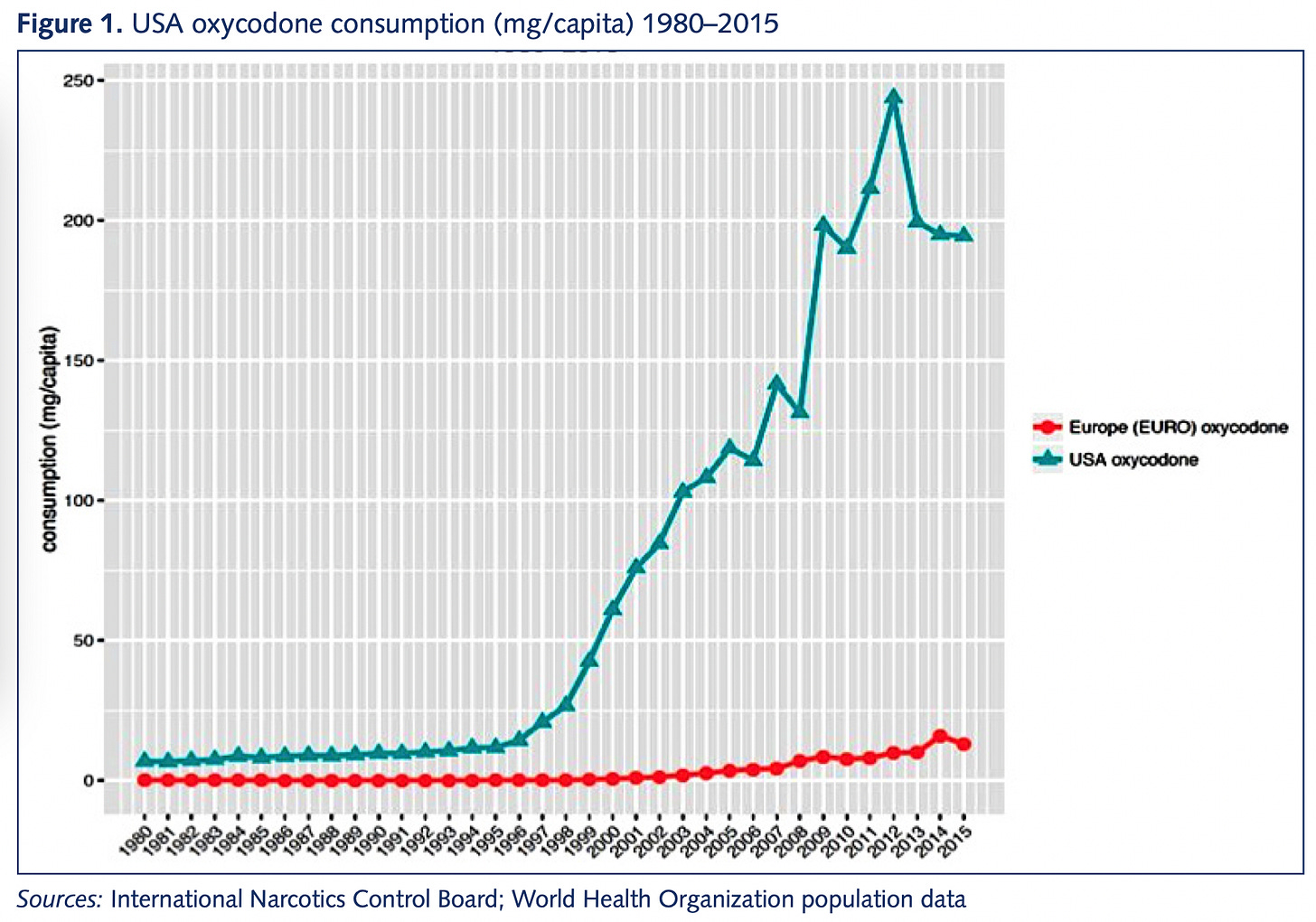

As outlined in “Empire of Pain,” America’s devastatingly difficult opioid epidemic stems from profit-seeking pharmaceutical companies talking people into the idea that opioids are a useful treatment for chronic pain.

Chronic pain is a very real problem. You can understand why people were strongly motivated to believe that a great new treatment option was available; it just wasn’t true. But in America, there was a lot of money to be made off of accepting the pharmaceutical companies’ claims. This was not the case in Europe, and that led to a significant divergence in prescription practices.

And while it’s easy to lay all of the blame on the Sacklers and the pharmaceutical industry, the doctors who do the prescribing deserve a share as well. In America’s marketized, entrepreneurial health care system, a medical doctor is often also a small businessman whose job is to gin up business and drive sales. If a new product hits the market and 90 percent of the profession is cautious and responsible about its use, that’s a chance for the other 10 percent to gain market share.

The market for quacks

One of the most striking things about health care is that the profession of doctor existed long before there were any scientifically valid medical treatments. When George Washington got sick, he was treated by a panel of doctors who bled him to death. People didn’t go see doctors as much back then as they do now, but there were plenty around — it was a distinguished and high-status field, even though practitioners had no idea what they were doing.

Modern medicine is obviously a lot better than that, thankfully. But the same underlying dynamic still exists — there’s plenty of money to be made selling supplements or “alternative” medicines that plainly don’t work. When people are suffering, they will pay money for treatments whether or not there is solid evidence that the treatments are good for them.

We also see a lot of this in the unregulated supplement market. A 2017 Consumer Reporters article says “Liver Damager from Supplements is on the Rise,” echoing problems that I’ve seen reported on going back to 2012 and which have been the subject of continuing work in subsequent years.

In 2019, Robert Fontana and Ammar Hassan, two liver doctors at the University of Michigan, reported on health risks associated with supplements:

These products are often purchased at health food stores or online in bulk. Over the past two decades, a significant increase in the incidence of liver injury related to the illicit use of [Annabolic Androgenic Steroids] AAS has been reported.

“Bodybuilding supplements that contain AAS can lead to liver damage, including severe cholestatic hepatitis, which can take months to resolve,” Fontana says. “Additionally, various multi-ingredient nutritional supplements taken to enhance energy, increase performance and facilitate weight loss can lead to potentially severe, or even fatal, liver damage.”

The dangers associated with overconsumption of steroids are pretty well known, but the authors note that overconsumption of green tea extracts also leads to liver damage.

And while actual medicines are more tightly regulated, the FDA doesn’t step in to prevent aggressive sellers with asymmetrical information from selling people treatments that may not be useful.

Medical practice often isn’t what it should be

Caesarian sections save lives and have for a long time. A C-section is also a major surgical procedure that is difficult to recover from, especially because the patient also typically has to care for a newborn baby. So ideally, doctors would perform this surgery only when necessary, not just willy-nilly. Yet as Lauren Sausser writes for Kaiser Health News, the extreme regional variation in C-section rates prompts the suspicion that doctors in the high-rate areas are reaching for this option too aggressively.

Sausser also notes some suspicious temporal patterns:

Some physicians say their rates are driven by mothers who request the procedure, not by doctors. But Dr. Rebekah Gee, an OB-GYN and former secretary of the Louisiana Department of Health, said she saw C-section rates go dramatically up at 4 and 5 p.m. — around the time when doctors tend to want to go home.

And as Gee explains, part of the issue is payments. A lot of states have their Medicaid programs structured so that from a doctor’s point of view, a C-section is not only faster but more lucrative. You don’t need to assume any cartoonish malfeasance on the part of providers to see how the objective structure of the incentives could bias their decision-making.

At any rate, I’m not really saying anything new here. Everyone who writes and thinks about health care has been saying for years that America’s system of rationing health care based on the ability to pay leads to overtreatment of some even while access is denied to others. Some recommended reading if you’re interested:

“You’re Getting Too Much Health Care” [Jamie Santa Cruz, The Atlantic, 2013]

“How to stop the overconsumption of health care” [Eve Kerr and John Ayanian, Harvard Business Review, 2014]

“Overkill: An avalanche of unnecessary medical care is harming patients physically and financially. What can we do about it?” [Atul Gawande, New Yorker, 2015]

“Too much medical care: bad for you, bad for health care systems” [H. Gilbert Welch, Stat News, 2017]

“Unnecessary medical care is more common than you think”1 [Marshall Allen, Pro Publica, 2018]

You can also find more academic treatments of the issue like “Overtreatment in the United States” with a team of authors in PLoS One from 2017. The BMJ has a “too much medicine” initiative.

Indeed, the hypothesis that American medical professionals’ income is inflated by billing for unnecessary care isn’t even controversial among medical professionals. A 2017 Johns Hopkins survey of 2,000 physicians found the controversy is why (not whether) doctors are billing people for so much unnecessary care — survey responses indicated that “physicians believe overtreatment is common and mostly perpetuated by fear of malpractice, as well as patient demand and some profit motives.”

Obviously doctors like the malpractice theory because it is more flattering to them than the profit motive. But as Aaron Carroll details in this JAMA Forum, the malpractice concern is a minor factor at best. Malpractice laws vary from place to place, for example, but doctors don’t tend to change their clinical practice when they move.

Doctors are selling products to clients. As with anything else, your best case scenario is to have a product that’s genuinely useful. But on the margin, your incentives are to sell aggressively — a pattern you see in any industry.

A plot twist

So this is all pretty boring, conventional wisdom stuff. The problem of overtreatment has been widely discussed in the United States for years, and while there’s plenty of disagreement and controversy about it, every significant institution I’m familiar with sees it as (1) a real phenomenon in general and (2) a plausible hypothesis for explaining specific trends.

For example, if you say that ADHD is overdiagnosed or anti-depressants are overprescribed, people may argue with you about whether your claim is accurate, but the question itself is seen as a reasonable concern. And in particular, if I were to say not that ADHD is overdiagnosed in general, but that there are specific doctors who are known for handing out Adderall like candy, then I think it becomes totally uncontroversial (read my mentions here to see how little controversy this stirred up). Googling “want to get Adderall fast,” you can even see people buying ads against that search term touting their “patient-first & judgement-free” approach to prescription stimulants.

Where this kind of boring take is going to rocket to nuclear strength heat is that I was thinking about these long-running overtreatment issues when I read an article about the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria in Amsterdam.

The clinic launched in the 1970s at a time when gender dysphoria treatment was rare and stigmatized. In the late-1980s, they first treated a 12-year-old and also developed the world’s first protocols for treating trans teens. But over time, what was once seen as the most forward-looking and supportive clinic for gender-affirming health care has come to be seen as a hyper-cautious dinosaur compared to contemporary American gender clinics.

And in the United States, where the number of gender clinics has, in de Vries’ words, exploded, many clinicians favor swifter assessments and the provision of puberty blockers, hormones, and gender affirming surgeries for young people at or near the moment they present with gender dysphoria. The careful therapeutic assessments that the Dutch clinic provides between each intervention, these clinicians now say, are too conservative — and possibly harmful to some young patients who could benefit from more immediate interventions.

De Vries and her colleagues are aware of these differing philosophies, as well as the criticisms of the Dutch clinic’s more methodical approach to childhood gender transition. But they also believe that the scientific uncertainties obligate practitioners to provide sensitive all-encompassing support, and they argue that their stepwise and often slower pace allows them to do just that, while also providing children and their families needed room to more fully explore identity in all its complexity.

“We need time,” de Vries said. “And we take time.”

I think that if you tune out the culture war context in which this disagreement is situated, you have a specific instantiation of a general phenomenon here — the more entrepreneurial, market-oriented American health care system is more eager to make the sale — and there is a reasonable question as to whether an express lane to medication is in fact the right solution for public health. What’s different is that if I said, “I’m concerned that some doctors are overprescribing Adderall,” nobody would find that particularly interesting. Some might agree, others might disagree, but it wouldn’t be a huge deal. The notion that nursing homes are over-using medication to address the needs of people in their care because that’s faster and easier than labor-intensive interpersonal work is broadly accepted as fact.

The culture war context

In Texas, Greg Abbott and Ken Paxton have handed down directives to classify all medical treatment of transgender children as a form of child abuse.

That seems obviously outrageous to me (note that de Vries’ clinic has, to the best of my knowledge, an excellent track record of success with these treatments) and is also causing secondary problems as child protective services workers resign rather than enforce unjust laws, depriving Texas of the ability to investigate real child abuses. Florida, similarly, is moving to block all gender-affirming care for transgender youth which is a major overreach.

I would in particular associate myself with this letter from Florida health care professionals that appeared in the Tampa Bay Times (emphasis added):

While we agree with the Florida Department of Health that guidance surrounding care of transgender youth “requires a full, diligent understanding of the scientific evidence,” their statement fails to follow their own recommendations. Specifically, the Florida Department of Health cites a selective and non-representative sample of small studies and reviews, editorials, opinion pieces and commentary to support several of their substantial claims. When citing high-quality studies, they make conclusions that are not supported by the authors of the articles. And while they state that their guidance is consistent with recommendations from Sweden, Finland, the United Kingdom and France, in fact, none of these countries recommends against social gender transition, and all provide a path forward for patients in need of medical intervention. This stands in marked contrast to the categorical ban recommended by the Florida Department of Health.

The way a lot of people approach the world is that when something bad is happening, as it is in Texas and Florida, they don’t want any intra-coalition quibbling or infighting. So progressives see that Ron DeSantis claims to be acting in accordance with the Swedish, Finnish, etc. guidelines and then criticize him for lying and leave it at that.

But the reason Florida cited those foreign guidelines is that it really is true that Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare has adopted a more conservative approach to the use of puberty blockers than the current American standard, just as the Dutch clinic that pioneered gender-affirming youth care is more conservative than American clinics. And while the question of whether Texas and Florida have gone too far in restriction is important, so is the question of whether Sweden is right or American advocates are. And while I’m not certain about the answer to that question (though my guess is that Sweden is closer to the mark), I’m really certain that it is not currently getting the rigorous in-depth treatments that it deserves.

It’s good to analyze important questions

Why do I think that Sweden is probably right about this?

I’ll be upfront: it is not because I’ve made a detailed study of the specifics of the issue. It’s because there are two competing potential explanations for the gap:

The Swedish health and medical establishments are more beset by bigotry and transphobia than the health and medical establishment in the United States.

The structure of the U.S. health care system is more entrepreneurial and market-oriented, and thus more inclined toward a “more, more, more” approach to treating everything.

As I think we saw before the plot twist, people seem to accept (2) as a general characterization of American health care. By contrast, (1) seems sociologically odd. The United States is much more religiously observant and traditional in gender norms than northern Europe. Sweden legalized same-sex marriage six years before the United States (the Netherlands was 14 years ahead), had an openly gay cabinet minister (in a center-right cabinet) over a decade before we did, and is in general almost universally considered to have a more progressive society and politics.

But what about the specifics? It’s hard to say. I’m not a doctor. I’m not a health and science reporter. I did run this take past a few left-of-center medical professionals who are not specialists in the field, and they broadly agreed that they think there are pockets of overly aggressive use of puberty blockers reflecting a general tendency toward overmedication in American health care. I also know that in the media, this is a bit of a taboo subject that nobody really wants to look into. Not because you “can’t” look into it exactly, but because it would mean switching lanes from being a mild-mannered health and science reporter to being a subject of culture war controversies. Some people like that kind of thing, but most do not and prefer to stay away.

You’re starting to see a little tip-toeing away from this posture in pieces like Corinna Cohn’s Washington Post op-ed “What I wish I’d known when I was 19 and had sex reassignment surgery” and this LA Times profile of Erica Anderson, a trans woman psychologist who supports gender-affirming care for some kids but also thinks we have cases of overly aggressive transition.

That’s good to see. But ultimately we are going to need America’s editor community to encourage the health and science journalists they would normally assign to a story about potential overly aggressive treatment to do normal acts of journalism on this topic and to be prepared to defend them against backlash. This is a sensitive subject and it is absolutely true that work done in this area may be misused or misappropriated by bad actors or bigots. But the question of why the U.S. guidelines are more permissive than the northern European ones is a totally valid journalistic question, and “they’ve all been brainwashed by Greg Abbott” doesn’t seem like a plausible answer to me.

Not more common than I think — I’d read all those other articles.

Just to echo what Milan said — everyone be on your best behavior and try to achieve maximum calm and respectfulness in your choices of language and manner of addressing others.

Bravo on including an honest-to-god end of second act twist in an opinion column