How natural gas powers renewables

A case for fracking ... but mostly a case for nuclear, geothermal, and hydro

Lately I’ve been getting targeted natural gas industry ads featuring former Democratic Senators Mary Landrieu and Heidi Heitkamp making the case that natural gas and renewable energy shouldn’t be seen as enemies and are, in fact, are best friends. Politico even has a sponcon article by the senators with the headline “Politics Aside: The fact is natural gas is accelerating our clean-energy future.”

Sadly, the natural gas industry is not giving me any money, but I find their basic argument here persuasive; it seems both factually true and also somewhat underappreciated by the world at large.

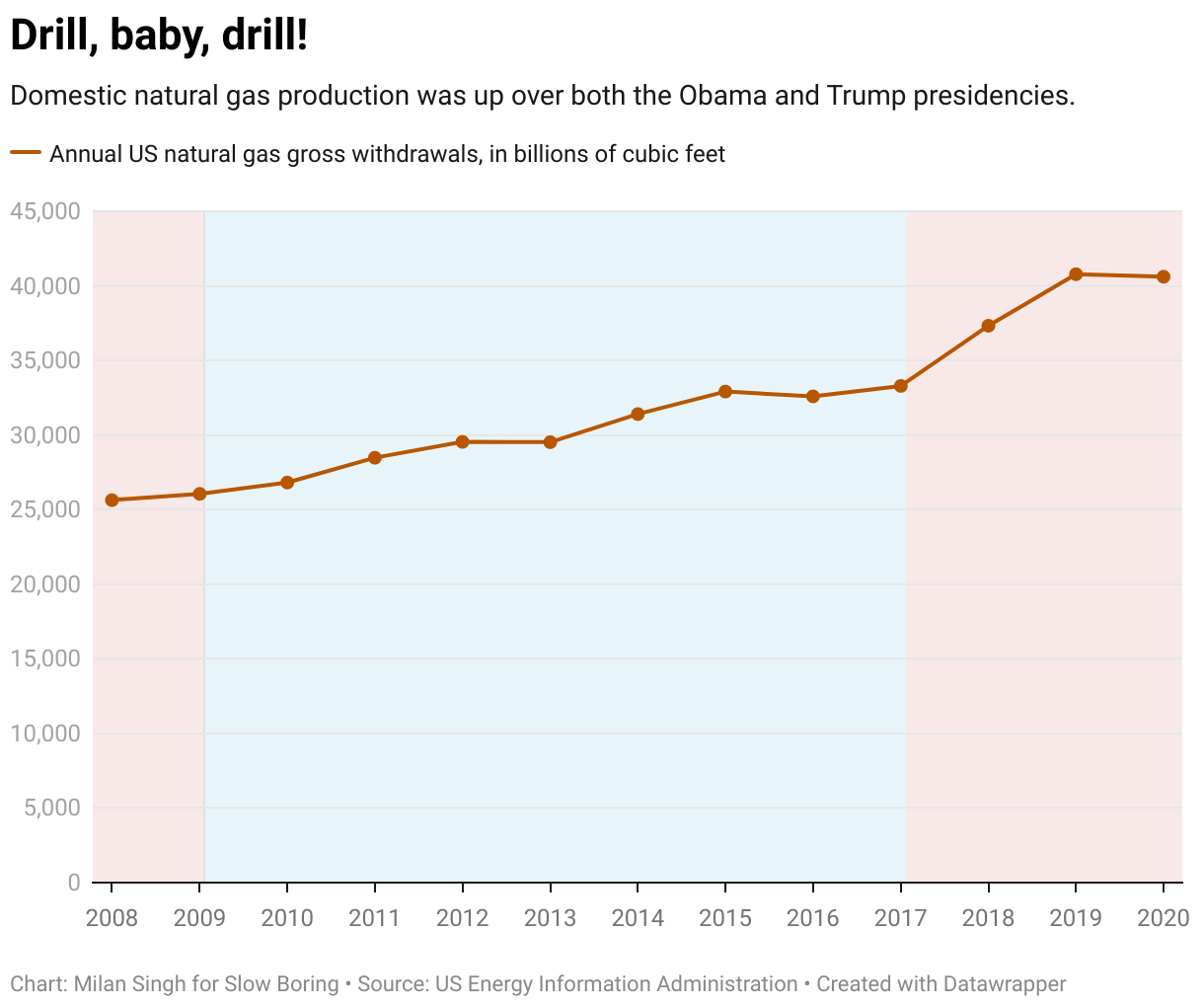

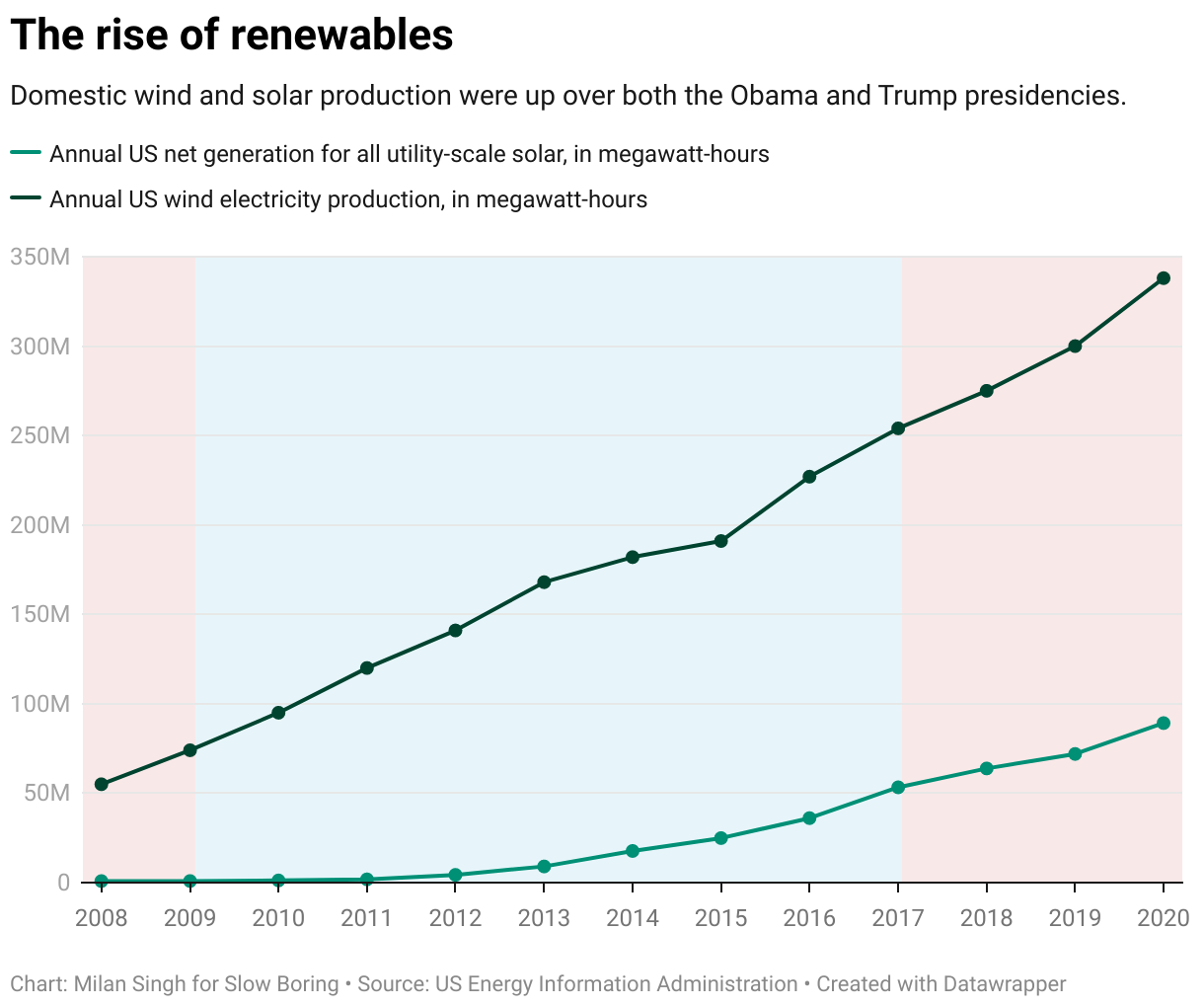

When Barack Obama was president he talked a lot about his efforts to accelerate renewable energy, and in fact renewables surged an incredible amount. But so did natural gas. When Donald Trump was president, the politics and the rhetoric both flipped and gas production surged even more. But so did renewables. And this isn’t a coincidence or weird historical irony; there’s a deep complementarity between solar and wind power on the one hand and natural gas on the other.

Where I break with the paid shills, though, is that it seems to me that there are two sides to this coin.

The industry is correct that people who care about the environment should probably be less critical of the natural gas industry. In addition to its complementarity with solar and wind, gas has lower emissions than coal or oil. Environmentalists really should see increased gas production as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, at least on the current margin.

But a zero-carbon electrical grid can’t burn natural gas. And the upshot of the complementarity, in that case, isn’t so much that natural gas is good but that driving fossil fuels off the grid is very expensive with a strategy focused solely on wind and solar. Abandoning fossil fuels is going to mean also embracing some combination of nuclear, geothermal, and hydro.

Gas and renewables are special friends

Here are some stylized and somewhat simplified facts about energy:

It’s easy to turn gas and hydro plants off and on to generate electricity in response to demand.

Coal and nuclear plants are hard to turn on and off; they work best when they run constantly.

Solar panels and wind turbines produce a variable amount of electricity depending on how sunny or windy it is at any given time.

Demand for electricity varies both according to the time of day (we use less when people are asleep) and according to the season (we use more in the summer when air conditioners are on).

A lot of stuff, notably cars and home heat, that is currently powered by fossil fuels could be converted to electricity with existing technology.

Points (1) and (3) make natural gas and renewables very good complements.

The cost of generating electricity via natural gas is largely the cost of buying the gas and burning it. By contrast, renewables have very low operating costs. The cost per megawatt of a utility-scale solar plant is basically the cost of building it divided by the number of megawatts it generates. So if you go build the plant somewhere that gets a lot of sunshine, your cost per megawatt is very low.

But in practical terms, the question a utility has to ask isn’t “what is the cost per megawatt of the electricity that the solar installation creates?” but “what is the total cost of relying on the solar installation?”

Now imagine building a solar plant in a community where all the power currently comes from natural gas. With newly installed solar capabilities, less gas is burned when the sun is shining and the community relies on cheap solar power instead. But if the community is instead currently getting all its power from coal, the calculus is different. A coal plant can’t simply be switched off during the day and then on again at night. In that case, the practical cost of making the switch is the cost of building the solar installation plus the cost of building a natural gas plant plus the cost of burning gas when the sun isn’t shining. From the utility standpoint, the question is about the all-in cost of making the switch — so the price of natural gas is just as relevant as the price of solar panels.

The big increase in domestic gas production, in other words, isn’t distinct from the increased use of renewables. Gas, wind, and solar teamed up to crowd out coal.

And in doing so, they did a lot to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and clean up the air. Gas is cleaner than coal, and gas + renewables is a lot cleaner.

So that’s the case for fracktimism — it’s cleaner than coal and it’s driven the renewables transition forward.

Renewables’ costs get worse on different margins

There’s this old joke in Maine about the fractal coastline and the sparse road network — “you can’t get there from here.”

And by the same token, while gas helps renewables move forward, the problem is that the intended destination is a world where you’re not burning the gas at all.

The issue isn’t that you can’t use solar power without a gas backup, but that the cost-effectiveness of renewables declines a lot when you’re not simply talking about flipping the gas switch on and off. Right now, renewables generate a small enough portion of our energy that each marginal solar panel delivers 100 percent of its electricity to the grid and we just burn less gas. But meeting 100 percent of peak electricity demand with renewables would still require burning gas on cloudy days. Adding more solar panels would decrease the amount of gas burned when it’s overcast. But since you were already meeting 100 percent of peak condition electricity demand from renewables, you’re now wasting electricity on the margin — that means the effective cost per megawatt starts going up.

In other words, when people say that renewables are cheap, they are completely correct, at the current margin. It would be very, very affordable to take wind and solar from their current 10 percent of the U.S. electrical system to 20 or even 30 percent. But as renewables get bigger, their cost profile starts getting worse.

That’s in part because gas complementarities get worse and in part because the most optimal locations are used first and subsequent builds have to settle for worse and worse ones.

To an extent, this can be fudged since over time people are switching to more EVs and heat pumps so aggregate electricity demand is rising. But in terms of a zero-carbon future, this in some ways makes things worse. Right now electricity demand is much higher in the summer than in the winter because people use electricity to cool their homes but (usually) not to heat them. This goes together nicely with the fact that there is more daylight in the summer. But to switch from gas-powered home furnaces to heat pumps powered by renewables is tough given the short winter days. There’s wind, too, of course. But to be really assured that people will be able to heat their homes in December and January, you’d need massive overbuilding of wind/solar relative to electricity demand during more benign conditions.

Again, I want to be clear that I’m not saying this is impossible — people have been arguing about it for years, and you could do it if you wanted to. My point is simply that the actual progress that renewables have actually made in the actual world has been driven by complementarities with gas. An all-renewables grid is a different idea entirely and one with fundamentally less appealing economics.

Other ideas probably have lower environmental impacts

This whole time I’ve been talking about gas, wind and solar, and coal. But there are of course other energy sources.

A really ideal one for these purposes is hydropower because hydro, like gas, can be turned on and off. With pumps, hydro can even be made to run backward and can be used as long-term storage. So a country like Norway that has tons of hydropower can use it in lieu of gas as a solar/wind complement and go down to zero use of fossil fuels. It’s funny that the country best-positioned for that outcome is also sitting on top of huge oil and gas reserves, but that’s why the Norwegian center-left has a pure energy abundance strategy, focusing a lot on electrification and renewables while doing nothing at all to reduce fossil fuel production. The plan is to have a zero-carbon economy that also exports tons of fossil fuels until the rest of the world stops burning them.

This is also why the environmentalists who are criticizing a plan to build a big transmission line to bring hydropower from Quebec down to New York have lost the plot. If you want a renewables-centric zero-carbon strategy, then hydro is by far the best friend you have.

As a broader strategy, though, almost all of the really promising dams have already been built. But even if they hadn’t been, the ecological cost of damming rivers is non-trivial. And that’s the real issue here. There’s no such thing as a way to make electricity that doesn’t have some kind of ecological footprint, and that includes the renewables themselves. After all, the escalating cost of renewables once you run out of gas complementarities really just amounts to the fact that you need to build more stuff. However many wind turbines and solar panels get you to a 50 percent renewable grid, you can’t just double that number to get to 100 percent — you’re dealing with worse locations and times of day when there’s less wind and sunshine, so you need to build redundantly and enhance with batteries.

That represents a financial cost, but it’s also a literal consumption of open space. I think that if you look at it in a fair-minded way, the potential environmental cost of drilling more holes in the ground for geothermal exploration or setting aside more sites for nuclear waste storage is quite a bit lower than the land use consumption that’s required by redundant build-out of renewables. Maybe some kind of huge technological breakthrough with batteries will ease some of these tensions, but the batteries themselves are made out of stuff that needs to be mined. So especially compared to geothermal, I don’t know why you’d have a strict preference for one kind of hole over another.

Long story short, the gas industry propagandists are onto something, and the success of renewable energy at the current margin is significantly dependent on the expanded output of cheap natural gas. To some extent, congratulations are therefore due to America’s frackers. But the real upshot Landrieu-Heitkamp Thought is that the government should be friendlier to nuclear and advanced geothermal power. These industries aren’t paying me either (though I do have an Oklo-branded coffee mug), but more to the point, they don’t seem to be paying anyone in Washington enough to get their ideas prioritized.

This is a shame because a future of abundant zero-carbon energy probably requires more emphasis on non-solar/wind sources of zero-carbon electricity. The cheap renewables buildout is really, in part, a natural gas buildout.

The real question:

Is Matt in the pay of Big Gas? Big Solar? Big Wind? Big Nuke?

Or is it....

[jarring chord]

All of the above?

I thought this was very interesting, but this open-space argument seems pretty overblown to me. Didn't you write a book about how America is really large?

Also, offshore windfarms are a thing, and roof-like solar panels for crop fields that double-serve as protection against hail etc. already exist. Plus, natural gas also takes up a lot of space because you need to build pipelines.