Europe should look at hard rationing and price controls for natural gas

This is it boys, this is war

Europe has a problem this fall and winter as the temperature drops — now that supplies from Russia have been largely cut off, there is a shortfall of natural gas.

This is really a threefold problem because gas is used in three major ways. On the one hand, it’s an important source of home heating fuel. On the other hand, it’s an important source of electricity generation. And on the third hand, it’s used for direct applications in industry, especially related to chemical manufacturing. The electricity itself is then split into household and industrial use, with something like the competitiveness of European metallurgical companies closely linked to the price of electricity.

Last but by no means least, it’s worth recalling that the growth of renewable electricity does not really offer an exit from gas’s relevance in this sphere. When people calculate the levelized cost of an offshore wind facility, what they are doing is taking what it costs to build the thing and then dividing that by the amount of electricity it generates over the cost of its useful life. But the way an electricity grid works is that you need to generate enough power to meet all the demand or else the grid breaks. So if wind is meeting 90 percent of your needs on average (more than that on the windiest days, less on the days when wind is light), gas is still the source of your marginal megawatt. The price of electricity in an unregulated spot market1 is going to be the price that matches the marginal supply of gas to the marginal demand for electricity. So a sudden shortage of gas is going to create very high prices as long as you are relying on gas to balance your grid. Switching at the margin to more renewables creates less pollution and sends less revenue to gas-producing countries among other benefits — but it doesn’t escape that bind.

In response to this crisis, lots of European governments are breaking out the subsidies. That’s been part of the fiscal crisis in the U.K., but we also see the German government moving to roll out extensive subsidies. Then there are concerns that German subsidization is only going to push prices even higher in other European countries that are less able to afford it. By the same token, much of the gas that’s no longer flowing to Europe via pipeline can’t get out of Russia through any other means of egress either. Europe is replacing as much of it as they can with imports of liquified natural gas (LNG) which is pushing up prices throughout the global LNG marketplace. In the case of New England, that’s a problem. But in the case of poorer countries, it’s going to be a disaster. As with the food crisis of the past spring, Russia is trying to hurt its antagonists with this commodity warfare but the sharpest pain is being felt in non-aligned states.

But this all points to the fact that in my view, Europe really needs a different approach to energy this coming winter — one that relies less on a mix of market mechanisms and subsidies, and more on explicit rationing and price controls.

A bad idea whose time has come

Back in May, when Elizabeth Warren and others were blaming inflation on “corporate greed” and pushing legislation that would empower the FTC to ban excessive price increases, I wrote a post arguing that “Greedflation is Fake.” I also made the case that Warren’s effort to back us into an economy driven by price controls would necessitate creating a big rationing system, and responding to a rise in grocery prices by creating a system of rationing and price controls would be destructive overkill:

Warren is correct that it’s not a law of physics that a surge in demand needs to lead to a surge in prices.

When Ben & Jerry’s holds a free ice cream cone day, they get a surge in demand. They could respond to that surge by raising prices to a non-zero level to improve profit margins, but that would kind of wreck the marketing gimmick. You just get a situation where the line is very long and you need to wait a while for your ice cream. As a once a year promotion, that’s kind of fun. But in general, an economy where you need to spend tons of time standing in line waiting for things is kind of a bummer. Time wasted in queues is a real loss.

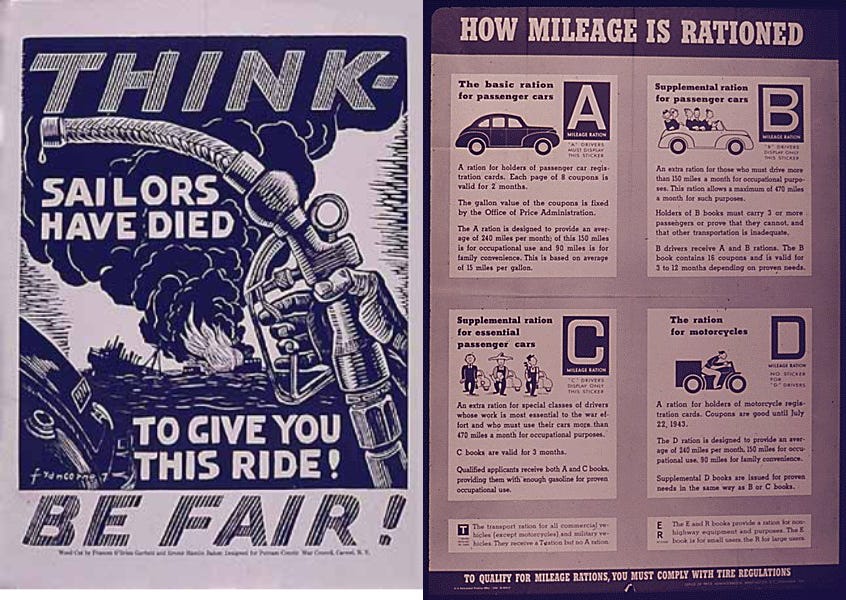

At times, it probably is appropriate to respond to economic problems with a mixture of rationing and price controls. During World War II one of my grandfathers was a radioman on Navy planes, and as a kid I loved to hear his stories about combat in the Mediterranean Theater. My other grandfather was an economist in the Office of Price Administration working specifically on footwear, which when I was a kid seemed awfully boring. The military needed tons of boots for the troops and rubber for tires. But civilians also needed shoes; in particular, people in certain critical industries needed work boots. So there was a whole system of shoe-rationing and price controls to try to make sure that the country’s footwear-production capacity was mostly turned toward military uses. Now that I’m a grownup, I find this aspect of the war more fascinating in a lot of ways.

Today we seem to be moving toward a system of soft rationing and price controls to address shortages of baby formula. That seems appropriate for that specific sector given the emergency. But note that the formula shortages are in fact caused by a negative shock to supply — one of Abbott’s big factories was shut down for health reasons, and ultimately the only real solution here is to get the factory back running.

You certainly could apply this kind of logic broadly to today’s economy. Meatpackers’ profit margins soared recently, and you could have had regulators prevent them from raising prices. But what happens when demand soars and you don’t raise prices? Well, you sell out of stuff. And if people started regularly going to the store and finding that all kinds of things were sold out, they’d start panic buying whatever wasn’t sold out in order to stockpile (the prices would be low after all). And the panic buying would just lead to more shortages. Then to fix things, you’d need a real government rationing system — so much bacon per week, so many eggs, etc. And then you’d have illicit trade in ration coupons, a black market, the whole deal. And for what? To address a temporary baby formula crisis induced by the shutdown of a plant, it makes sense. To defeat the Nazis, you do drastic stuff.

Putin is not Hitler and contemporary Russia is not Nazi Germany.

But Europe is in basically a “wartime” situation. Russia invaded Ukraine, and Europe has been a willing participant in a western-led response whose key modes are (a) denying Russia access to crucial imports it needs to sustain its military-industrial complex, and (b) provisioning Ukraine with a quality and quantity of military hardware that it could not possibly afford on its own. Russia is retaliating as best it can by attempting to wreck Europe’s economy.

And Europe ought to respond to this geopolitically induced crisis in a collective, strategic way — with economic consequences rather than a purely economic catastrophe that should be addressed with market tools.

You can’t leave it up to the market

Of course, one thing you could do is say, “well this shock is nasty, but the best course of action is just to leave things up to the free market which will make the optimal adjustment.”

In a lot of contexts pure market solutions are underrated, but not in this one. The big issue is that people die if they can’t get their homes warm enough in the wintertime, but also normal people prefer to keep their homes at a temperature that is much, much, much warmer than what is needed for survival. And people put a very high value on that kind of comfort. An affluent person is going to respond to an energy price shock by drawing down savings while continuing to heat his home to 20 degrees, or maybe budge just a bit down to 19.2 And a person who's seriously pinched by energy costs is going to cut back on non-energy luxuries before turning down the heat. That relatively inelastic demand on the part of the more affluent segments of society means that people with lesser means can find themselves pushed below subsistence heating levels to the point where their health is in serious danger. This is part of a broader set of phenomena where background conditions of inequality make pure market allocations inefficient from a welfare perspective, and it’s why — as far as I can tell — every government is trying to find ways to shield the poorest from the full impact of the gas crunch.

But the other issue is that gas is both a household consumption item and also an input to industry.

If the input costs of industrial production go up, so will the prices. To an extent, those higher prices will be passed on to consumers. But those industrial outputs are also traded globally. So European industrialists will have only a limited ability to pass costs on to consumers who will instead switch to foreign products. Now of course the world as a whole has only limited production capacity, so a newly high-cost European industry won’t totally vanish. But it will shrink considerably if market forces are allowed to play out. That’s going to mean lots of workers losing their jobs and then needing extra support from the welfare state.

To the extent that we think higher prices are a new normal that the whole continent needs to adapt to, that’s fine, and a combination of flexible markets with a generous welfare state is the best option. But to the extent that we think higher prices are a wartime emergency that will fade away as Europe responds with more non-gas energy sources and more LNG terminals, then it’s very inefficient to incur all these costs of layoffs on the back-end through the welfare state. What you ought to do is spend money to keep the factories running and keep people employed.

So you end up with strong cases for subsidizing both industry and the poor.

You can only subsidize so much

Unfortunately, there are multiple problems with a subsidy-centric approach.

One is that, as seen in the United Kingdom, there are simply limits to how much the public treasury can bear. The U.K. is physically disconnected from the European gas pipeline network and now entirely outside of the European Union economic architecture, so they are free to spend as much as they want to in order to maintain 100 percent of pre-war gas usage. But that necessarily comes at the expense of some mix of currency decline (which raises the price of everything that isn’t gas) or higher interest rates. The effort by Liz Truss’s government to guarantee a fixed price of energy and achieve it through subsidy rather than price controls has essentially recreated the problems of a currency pegged to gold.

Eurozone members don’t have that fiscal and monetary flexibility, and in many cases are simply not going to have the funds needed to subsidize their way through the winter.

Germany maybe will since they are relatively rich and also ran tight fiscal policy for the previous 20 years. And since German politicians have insane views on fiscal policy, they will probably say that the current experience actually validates their prior two decades of excessively tight fiscal policy. In reality, the current situation mostly shows that Germany wasted an opportunity to take advantage of a prolonged period of negative interest rates to create a national high-speed rail network3 and to make massive investments in home insulation. They also really screwed up with their post-Fukushima turn against nuclear power, but that's another story.4 But the key issue is that beyond the specifics of the German situation, everyone on the main European gas grid is fighting over a quantity of LNG that is limited by the throughput of the existing terminal infrastructure. So if European Country A spends money to get more gas for its citizens, that means less gas to go around for European Country B. Having all the fiscally stronger European countries bid against each other like this is not going to accomplish anything productive.

In some cases, you would say “well this soaring spending is the signal we need to spur investment.” But Europe is already building new LNG terminals as fast as they can, and other relevant supply-side issues like trying to turn back on the shuttered nuclear plants or legalizing fracking are regulatory issues. There isn’t some price point at which the plants turn back on; the government would need to decide it wants to turn them on (and they should).

What has to happen is that someone needs to use less gas. And while most countries seem to be trying to design tiered subsidy schemes that will somewhat encourage that, any plan that relies heavily on subsidization will necessarily mute the demand response.

Wartime energy policy

If you think back to World War II and the limited oil supply situation, the government articulated some clear priorities.

They needed oil to actually prosecute the war — to keep tanks and planes and ships going. They also needed oil for war production, including both direct use in factories but also the whole long supply chain that benefits from trucks and tractors. Last and very much least, they wanted civilians to be able to have an okay quality of life.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.