If you want to talk about racism, talk about racism

But don't go out of your way to inject race into race-neutral policy arguments

Yale political scientists Micah English and Joshua Kalla have a new pre-print paper out that helpfully explores a question we’ve addressed a couple times at Slow Boring — how does it impact public opinion when you frame arguments for race-neutral economic policies in terms of closing racial gaps?

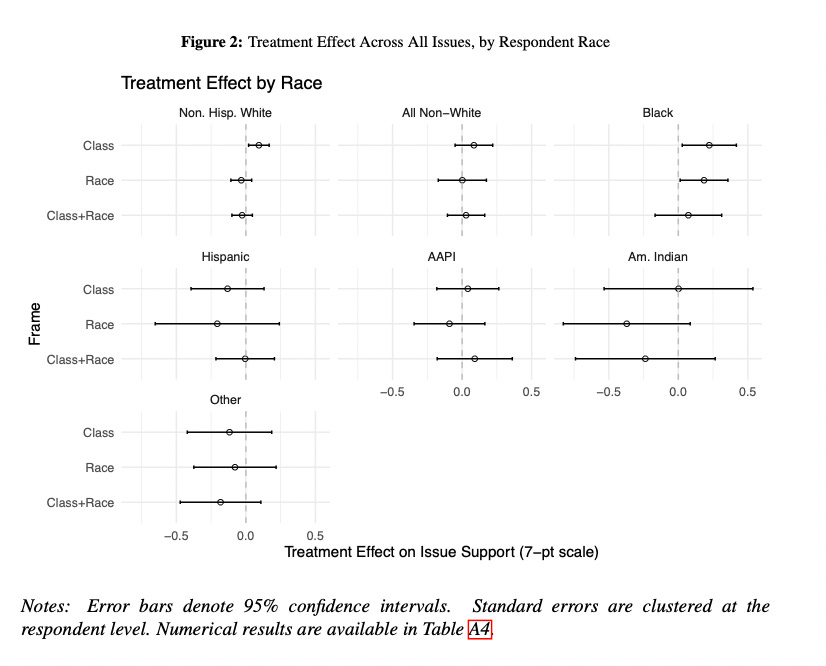

Specifically, they look at raising the minimum wage to $15/hour, forgiving $50,000 in student loan debt, upzoning housing regulations, the Green New Deal, Medicare for All, and a House bill to implement marijuana reforms including federal decriminalization. They find that pooling all issues and respondents, an argument grounded in economic class is mildly persuasive and moves people toward the progressive position. Conversely, arguments grounded in racial issues (or that blend racial and class arguments) are mildly counterproductive.

The paper has a bunch of other charts, but I think the most important one is the racial breakdown. It shows that Black respondents find the racial equity arguments more convincing than white or Hispanic respondents do. But the Black respondents also find the class arguments more persuasive than the racial ones. The only ethnic subgroup for whom race-forward arguments are more persuasive is “Other”, which is a small group with large errors, and in most cases, I think not the target audience of elected officials strategic calculus.

This all seems clearly correct to me, but it has obviously annoyed certain segments of academic Twitter. But I think it’s very important, so rather than reading the room and not making trouble on this front, I want to emphasize both the limited scope of this controversy and also the importance of digesting the point.

But here’s the key thing — English and Kalla aren’t testing whether it’s a good idea to talk about racism. And I’m not saying politicians should shy away from tackling race-specific issues when they arise or seem important. The narrow — but important — question here is should you take an issue like the minimum wage that is not on its face about race and go out of your way to inject race into it? And the answer, I think, is no.

Not everything is about class

There is plenty of evidence of racial discrimination in the United States.

The Stanford Open Policing Project finds strong evidence of racial discrimination in police stops.

There is evidence across multiple audit studies of discrimination against job applicants with stereotypically Black names (though there are also suggestions that this may be intertwined with issues about parental educational attainment).

Abigail Wozniak finds that when employers are encouraged to impose mandatory drug testing on their employees, they hire more Black workers, suggesting that in the absence of tests they are simply assuming Black people are likely to be drug addicts. Jennifer Doleac and Benjamin Hansen similarly find that policies which prohibit employers from asking applicants’ criminal records actually “decrease the probability of employment by 3.4 percentage points (5.1%) for young, low-skilled black men.”

There’s evidence that teachers are racially biased in their expectations for school kids, and that this contributes to poor educational outcomes for Black kids.

If you care to Google around, you can find more studies on different subjects. The main idea here is that these are topics where we don’t just observe racial “gaps” in outcomes, but rather actual evidence of discrimination. Oftentimes it’s what economists call “statistical discrimination,”1 or what when I was a kid we were taught to call “stereotyping” — people draw strong, often inaccurate, inferences about other people based on incomplete information. And that pattern of behavior can be a significant source of disadvantage.

Hillary Clinton famously took a shot at Bernie Sanders by asking “If we broke up the big banks tomorrow, would that end racism?” At some level, there’s a real element of truth in that2 — there is more to life than economic policy, and a politics focused solely on class issues is going to have significant blind spots. But the unfairness given the specific context of the primary was the idea that hesitancy to address specifically racial issues was somehow peculiar to Bernie Sanders when it actually represented the pre-2015 status quo in the Democratic establishment.

Obama and the “beer summit”

From the 2007 launch of his presidential campaign through to his successful re-election in 2012, I think the best way to characterize Obama’s treatment of racial issues in his rhetoric was massive, largely justified paranoia about white backlash.

Of course, racial issues stalked his campaign from the beginning, with his primary candidacy both attracting enthusiasms grounded in his identity and also racialized opposition. But in his public rhetoric, all Obama ever did was push back on racial polarization, at times in disingenuous ways. In his famous Philadelphia race speech, he scolded the media, complaining that “the press has scoured every single exit poll for the latest evidence of racial polarization, not just in terms of white and black, but black and brown as well.”

Obama was on the defensive in the speech over things the minister at his Black church in Chicago had said. And a key part of Obama’s strategy of distancing himself from Wright while still being loyal to the Black church was to talk about his grandma:

I can no more disown him than I can disown my white grandmother — a woman who helped raise me, a woman who sacrificed again and again for me, a woman who loves me as much as she loves anything in this world, but a woman who once confessed her fear of black men who passed her by on the street, and who on more than one occasion has uttered racial or ethnic stereotypes that made me cringe.

He’s trying to assure white America that not only is Barack Obama not an alarming angry Black man, he’s actually so chill that even if you do legitimately racist stuff, he won’t mind too much. Joe Biden ends up on the ticket not despite but partially because of his history of racial gaffes — like Obama’s white grandma, he is there to reassure nervous white voters that Obama isn’t here to give you a hard time about being racist.

It all came crashing down soon after Obama’s election when a neighbor called the police on Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. for allegedly trying to break into his own house. A confrontation between Gates and the officer on the scene, James Crowley, ensued — the exact details of which are still disputed — but that ended with Crowley arresting Gates on a disorderly conduct charge.

Obama was asked about it and said:

I don't know, not having been there and not seeing all the facts, what role race played in that. But I think it's fair to say, number one, any of us would be pretty angry; number two, that the Cambridge police acted stupidly in arresting somebody when there was already proof that they were in their own home, and, number three, what I think we know separate and apart from this incident is that there's a long history in this country of African Americans and Latinos being stopped by law enforcement disproportionately.

In his memoir, Obama recounts that White House internal polling registered the biggest drop in his approval rating of the whole presidency during the ensuing days as law enforcement organizations condemned the president. Obama backtracked on his remarks and wound up hosting a “beer summit” with Gates and Crowley, with Joe Biden also there in his reassuring white guy role.

The political lesson Obama took away from this was that race was indeed politically radioactive, especially for him and he should stay away from it.

The Great Awokening

I wrote a piece in April of 2019 arguing that American public opinion had undergone a “Great Awokening” of white racial attitudes.

And thanks to that shift, I think it’s now much more viable to actually raise the kinds of issues that Obama shied away from. The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, for example, polls pretty well even as “defunding” police is toxic. Three-quarters of the public, including 70% of whites, say the Chauvin verdict was correct.

I think one could actually make the case that traditional civil rights issues have become somewhat underrated in contemporary politics.

Why not bolster funding for the Department of Justice and HUD to do more audit studies and stings to detect and prosecute illegal discrimination? I don’t hear anyone talking about that kind of idea. And unlike in 2009, it’s not because everyone is terrified to talk about racism. I think it seems a little too basic and small-minded in some quarters to commit yourself to vigorously combatting illegal discrimination. But it seems like a pretty good idea to me.

Now to be clear, the basic Obama worry is always going to be with us. As long as the electorate is majority-white, making a big deal about your desire to help non-white people is a strategy that carries some risks. But it’s also true that sometimes you just have to do the right thing. The exact calculus of what it’s best to do quietly vs. loudly, and by whom, and in exactly which circumstances, is complicated. But there’s a strong case on the merits for pursuing antiracist policies and I think oftentimes a viable politics.

But what we are talking about with this new paper is something different — taking class politics and injecting race into it.

Doing racial politics backward

Back to the Obama years.

Here’s Ta-Nehisi Coates blogging in December of 2010:

Moreover, there is no demonstrable movement in the Obama administration, among black legislators, or even among black people to push for damages for slavery. On the contrary, “reparations” is something white populists yell when they want to rally their race-addled base. So for Rush Limbaugh, the way to understand food stamps, unemployment benefits are to “think forced reparations.” For Glenn Beck health care reform is not something that can be debated with facts and figures, but “the beginning of reparations.” And so it is with Steve King, that a suit brought to remedy actions taken within the last couple decades, are actually revealed as “slavery reparations.”

Some further thoughts: First, Beck and Limbaugh are employing a formula that has proven remarkably successful throughout American history — rallying against social investment because it might actually help a despised minority of the population. The cause of public education in the South, for instance, was long hampered by the notion that, however it might help poor and working whites, it might also help blacks too.

This is the classic racial politics of the American welfare state. Du Bois wrote of the psychological wage of whiteness that prevented the white worker from extending solidarity to the Black worker, with both ending up worse off as a result. In Heather McGhee’s metaphor (but also a real thing that happened), you drain the swimming pool rather than have integrated public goods:

In Montgomery, Alabama, I saw how racism destroyed a public good and the public will to support it. In 1959, the town drained their public swimming pool rather than integrate it. It was never rebuilt.

Coates famously does think there should be an explicit racial reparations program.

I also think he has no illusions about the difficult politics of that enterprise, which is one reason he’s withdrawn from the takes game — pop culture is almost certainly a more effective lever for shaping mass opinion.3

But when Coates says reparations, he means reparations. He absolutely does not mean expand public sector health care provision and call it reparations. That, he thought, was “something white populists yell when they want to rally their race-addled base.”

Recall that in English and Kalla, neither white nor non-white respondents prefer the racial framing, I think because it’s really weird. If you’re low-paid and also worried about discrimination in the job market and someone tells you they’re going to raise the minimum wage, that probably sounds pretty good. But if someone tells you the minimum wage increase is about fighting racism, then either you’re alienating someone with relatively conservative views on racial issues or you’re disappointing someone who might want to see racism tackled more directly.

Universal programs do a lot to help the disadvantaged

One of the works I always return to is William Julius Wilson’s 1987 book, “The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy,” which (among other things) contains the observation that “race-specific policies are often not designed to address fundamental problems of the truly disadvantaged.”

He has in mind things like affirmative action in higher education, which does not really help poor people regardless of race. By contrast, he says universal programs do a lot to help the truly disadvantaged and that he is “reminded of Bayard Rustin’s plea during the early 1960s that blacks ought to recognize the importance of fundamental economic reform (including a system of national economic planning along with new education, manpower, and public works programs to help reach full employment).” More so than from targeted, race-specific programs, Wilson argues that the truly disadvantaged reap “disproportionate benefits from a child support enforcement program, child allowance program, and child care strategy” and “they would also benefit disproportionately from a program of balanced economic growth and tight-labor market policies because of their greater vulnerability to swings in the business cycle of changes in economic organization.”

This Wilson/Rustin logic is, I think, the most defensible version of the racial framing.

Rustin is a civil rights leader urging other civil rights leaders to pay more attention to general questions of economics. Wilson is a Black intellectual urging other Black intellectuals to pay more attention to general questions of economics.

“In a sense, you could say we are engaged in the class struggle, yes,” Martin Luther King, Jr. told my grandfather days before he was shot dead. “It will be a long and difficult struggle, for our program calls for a redistribution of economic power.”

In my previous piece, I put forward a kind of narrow thesis about progressive foundations creating incentives for activists to frame their ideas in racial terms. After getting feedback from a bunch of readers, I want to broaden that out. I heard from one policy entrepreneur that he feels racial framing has helped her idea gain traction with Black members of Congress. I heard from a former staffer for a Black member of Congress that she feels racial framings helped her boss get media attention. One activist told me racial framings help build enthusiasm among other activists, which is important in practical coalitional terms.

A pet theory that I developed in the past but didn’t put into my previous piece is that we’re seeing carryover from college campus dynamics. If you convince an RA that a fellow student is doing something racist, the RA will probably put a stop to it, whereas simply observing that something is bad for poor people probably won’t get you anywhere. Connecting something to racism, in other words, can be a very powerful argument in certain contexts. But not in electoral politics.

Democrats really do this

The last pushback I’ve gotten in some quarters is that I’m going after a strawman. Activists or advocates may talk in this form, but real-world politicians don’t behave in the caricatured way that I’m suggesting.

But they do! Here, an example from the paper is the original White House fact sheet outlining Biden’s infrastructure plan:

President Biden is calling on Congress to make a historic and overdue investment in our roads, bridges, rail, ports, airports, and transit systems. The President’s plan will ensure that these investments produce good-quality jobs with strong labor standards, prevailing wages, and a free and fair choice to join a union and bargain collectively. These investments will advance racial equity by providing better jobs and better transportation options to underserved communities.

Biden personally is not a big practitioner of this sort of talk, so it tends to show up in either staff documents like that (or his executive order on Medicaid) or else to be exceptionally clumsy as when he said “our priority will be Black, Latino, Asian, and Native American owned small businesses, women-owned businesses, and finally having equal access to resources needed to reopen and rebuild” with reference to a small business initiative that had no such provisions.

The Title I education funding formula, similarly, makes no reference at all to race, but the Education Secretary is going out of his way here to make it seem like targeted assistance for non-white kids, tweeting “Across the nation, schools with the most students of color received, on average, dramatically less funding than majority-white schools. The new investment in Title I represents a major step towards correcting this injustice.”

Here’s Ro Khanna talking about universal healthcare (he does the same with minimum wage): “Fixing our broken healthcare system is critical to addressing racial and economic inequality. We need Medicare for All.”

Mondaire Jones talking about student debt relief says “as you heard earlier, this is an issue of racial justice, Black and Hispanic people disproportionately bear the brunt of the student debt crisis that I described. But I would also add if this is an issue of LGBTQ+ justice. Members of the LGBTQ community, largely because their families tend to disown them, disproportionately have higher student debt.” Chuck Schumer at that same press conference says “the wealth gap in America between Black and White is one of our greatest problems. And one of the amazingly enough, one of the greatest ways, quickest ways to cure a good chunk of it is get rid of that $50,000 in debt.”

And Elizabeth Warren: “We must keep up the fight to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. It's one of the cores of our fight for racial justice.”

The original instance of a politician doing this that struck me was Cory Booker’s insistence on framing baby bonds as a racial issue because back in the spring of 2018, it seemed to me that he was teeing up a presidential campaign based on Obama-esque efforts to downplay racial divisions.

I don’t want to be a tedious bore on this subject, but I really do think it’s important to try to drill down to ideas that make sense and not just go along to get along.

Framing race-neutral issues as racial ones is not the same thing as tackling racial issues head-on.

Framing race-neutral issues as racial ones is not politically effective, as racial justice advocates have traditionally understood the risks of white racial backlash are high.

Framing race-neutral issues as racial ones is not something non-white voters are demanding; Black and Latino people have economic interests and in the aggregate prefer seeing them discussed in economic terms.

Democratic Party politicians really do this a lot even though voters don’t like it, and broadly aligned groups in the nonprofit and media worlds do it even more.

I would like to see politicians simply stop doing it. But I also think that people whose job is not strictly electioneering need to take a deep breath and think about what it is they are trying to accomplish. The intention, I think, is on some level to help people. And the news that the currently fashionable tactics are ineffective is discomforting. But it’s much more important to actually help people than to avoid discomfort.

My recollection of pre-Great Awokening takes is that it used to be commonplace to argue that statistical discrimination is not bad or else not “really racist” as long as the underlying statistics are sound. So if a cabbie refuses to pick up a Black passenger on the grounds that Black people are more likely to live in peripheral neighborhoods, that’s okay because it’s not motivated by negative sentiments or an intent to harm. I think a useful Awokening contribution has been to reframe this around objective harms rather than subjective intentions and say that it’s bad when people are subject to discriminatory treatment, regardless of the precise reasoning that led to it.

An interesting, separate question is whether it was politically effective. She did very well with Black voters in 2016, which led many to conclude that this message was highly effective. I think the 2020 results in which Biden dominated the Black vote suggest another interpretation, namely that African American Democrats are simply more moderate and that the main impact of this message was to push moderate white Democrats to support Sanders in 2016 — supporters who he then lost with his more intersectional 2020 message.

“Ellen” and “Will & Grace” almost certainly did more to shape public opinion on LGBT issues than anything any columnist did.

I think most people are way more sincere in their worldview than others who disagree with them give them credit for. Race-forward advocates have as a core belief that racial disparities ARE racism, discrimination or no discrimination, and that this is our country's greatest moral failing. It is not enough to chip away at disparities unless it also comes with a moral conversion of the masses. I think a lot of us are far more attached to our underexamined core beliefs than we're willing to admit (this comic is so true: https://theoatmeal.com/comics/believe). The backlash to this conversation is a defense mechanism to defend the core belief that the moral rot of racism is a whites-over-blacks hierarchical thing and not a bias-and-stereotypes-about-people-based-on-race thing. By shifting the focus to class, a few uncomfortable dissonances come up for race-first thinkers. Perhaps minority elites have more in common with white elites than they do with low income minorities? Perhaps low income whites are equally worthy of empathy even if they are skeptical of racial justice issues? Perhaps the laws in our system that perpetuate disparities are really a direct function of class and only an indirect function of race? If this group acknowledges that elite minorities and their white allies have a significant amount of power as individuals and as a sub-group, it erases the idea that it's not possible for them to be "racist" about white people. That is a level of moral reckoning that group is not ready for. So studies like this touch a nerve.

I haven't read The Sum Of Us. I understand she is trying to make the "Race-Class Narrative" argument. The NYT article on this (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/28/opinion/biden-democrats-race-class.html) argued that a "race-class" message was a specific approach different than race, class, or the study's "class+race" approach. An example of extremely effective "race-class" messaging was this:

"No matter where we come from or what our color, most of us work hard for our families. But today, certain politicians and their greedy lobbyists hurt everyone by handing kickbacks to the rich, defunding our schools, and threatening our seniors with cuts to Medicare and Social Security. Then they turn around and point the finger for our hard times at poor families, Black people, and new immigrants. We need to join together with people from all walks of life to fight for our future, just like we won better wages, safer workplaces, and civil rights in our past."

It is obvious why messaging like this is effective. It is INCLUSIVE and inspiring. It makes "politicians and lobbyists" (who *everyone* hates) the bad guy, not white or middle-upper class people in general. Most people actually do want to help the less fortunate, they're just not all convinced the government is the most effective method to do so. And most Republicans are allergic to the idea that all Black people are dramatically "less fortunate" solely by nature of their race. They find that framing to be--wait for it--racist!

Advocates need to decide what is more important--making a material difference in people's lives or winning an ideological battle. They have assumed the battle must be won first, but the objective reality is that the battle is causing us to lose the war.

“But it’s much more important to actually help people than to avoid discomfort.” I’m genuinely afraid that this is simply not true among so-called woke, white, college-educated liberal progressives. I think that maybe being right, and being able to scold people, is what motivates them in many cases. I don’t think this is an intentional choice, or that they realize what’s going on, but when I call them (my friends) on stuff like this, the results aren’t pretty.