Stop marketing race-blind policies as racial equity initiatives

The country is already sold on a left-of-center economic agenda. Why complicate it?

This piece is written by Marc The Intern, not the usual Matt-post.

In a recent New York Times op-ed, Heather McGhee lamented that not only have conservatives used the concept of zero-sum racial conflict to undermine political support for public goods and a robust welfare state, but that “those seeking to repair America’s social divides can invoke this sort of zero-sum framing as well.”

“Progressives,” she wrote, “often end up talking about race relations through a prism of competition — every advantage for whites, mirrored by a disadvantage for people of color.”

If anything, she doesn't go far enough. The rise of this sort of progressive zero-sum racial rhetoric has accompanied the electoral backlash Democrats once hoped was limited to non-college whites but instead became a broad pro-Trump swing in all kinds of socioeconomically downscale communities during the 2020 election (Hispanics, immigrants of all stripes, maybe even Black people as well, while white voters swung towards Democrats).

There’s a growing trend both in media and among elected politicians of deliberately highlighting racial equity as a key argument in favor of left-of-center economic policies.

Two UC Berkeley economists writing in the NYT: “To Reduce Racial Inequality, Raise the Minimum Wage”

Two more academics writing in the NYT: “What Canceling Student Debt Would Do for the Racial Wealth Gap”

And it’s not just in the newspaper. In January, Cory Booker and Ayanna Pressley rolled out a proposal for “baby bonds,” emphasizing the idea that this program would help close the racial wealth gap.

President Joe Biden, 10 days before he took office, described his completely race-neutral small business proposals as prioritizing “Black, Latino, Asian, and Native American owned small businesses.”

None of the actual ideas are bad ideas. We should raise the minimum wage. We should cancel some student debt. We should give more money to poor people (baby bonds are just one way of doing this). We should help small businesses during a pandemic.

It’s also true that these ideas would disproportionately benefit people of color. After all, poor people in America are more likely to be non-white. Literally any policy that helps the poor regardless of race advances racial equity. This is not just true in theory — anti-poverty programs in this country have already reduced racial inequities.

But the premise of this style of argument seems to be that there are lots of people who are skeptical of race-neutral social welfare programs who will become more enthusiastic about them when the policies are framed as winners for racial equity.

With some help from the Voter Study Group, we can see that data clearly supports that this framing is counterproductive — almost everyone who cares a lot about racial justice also supports an expanded welfare state, whereas lots of people who support progressive economic policies have conservative views on racial justice questions.

Who are they convincing?

There’s a cliche of the “fiscally conservative, socially liberal voter” — the kind you might have met in college who scorned welfare but insisted he (probably a he) was in favor of gay marriage. These people certainly exist and are overrepresented among the college-educated and wealthy. But studies show that they’re somewhere in the neighborhood of 5% of the American electorate.

One notable 2017 study by Lee Drutman on 2016 voting found that these “libertarians” (his word for economically conservative but socially liberal voters) occupied around 4% of the electorate. A 2020 poll by Navigator Research, this time on 2020 voting, found that this group made up 5% of the electorate.

The other three groups are far more common. The Drutman study found that 45% of the 2016 electorate were “liberals” (left on economic and social axes), 29% were “populists” (left on economic issues but right on social issues), and 23% were “conservatives” (right on both axes). Navigator found that 46% of the 2020 electorate were left on economic and social issues, 17% were left on economic issues and right on social issues, 32% right on both issues, and only 5% right on economic issues but left on social issues.

The preponderance of populists over libertarians is a straightforward consequence of the fact that, per the below Data for Progress poll, even a decent share of Republicans support a lot of left-of-center economic policy ideas.

If you figure about half the country are Republicans, but then you realize about half of the Republicans are big fans of the welfare state, you come to the very simple conclusion that approximately a quarter of the country is “populist” — socially conservative but economically liberal. And the “populists” also include the socially conservative Democrats, who are more rare but also exist.

The 2020 Navigator toplines have these two questions side-by-side, which clearly show that there is large segment of the electorate who favors big spending on entitlement programs but is skeptical of Black Lives Matter.

Drutman’s team shared the underlying 2017 Voter Study Group survey, which allowed me to more specifically compare the size of the populist block to the number of what I’ll call “woke capitalists” — those who have left-wing views on race but right-wing ones on economics.

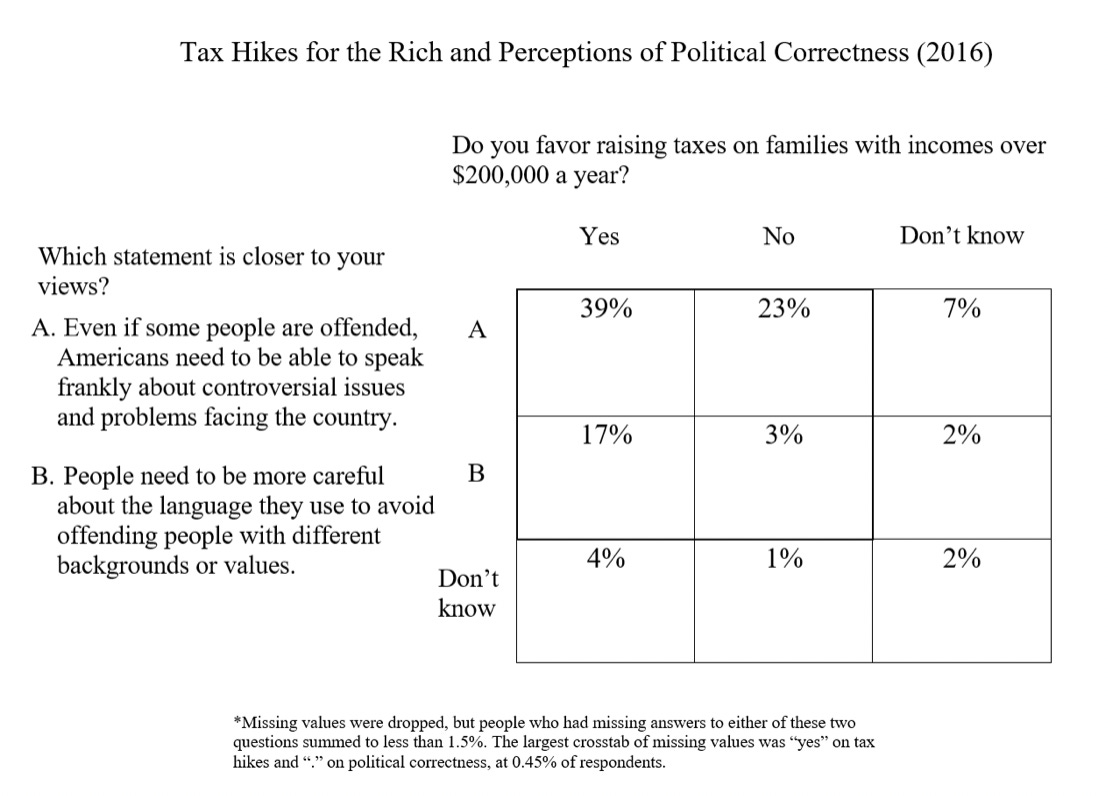

The main economic question I chose to analyze was this: “Do you favor raising taxes on families with incomes over $200,000 a year?” This is a stance that’s actually to the left of Biden’s position, given that he’s promised to only raise taxes on those making over $400,000.

If you pair this with questions on racial issues, you see that there are far more tax hike enthusiasts with conservative views on race than tax hike skeptics with progressive views on race.

Populists outnumber woke capitalists

The first race-related question in the Drutman study that seemed worth analyzing is this standard question on racial resentment that’s widely used in social science. I paired that with the tax increase question, and it’s clear that lots of people who give the racially conservative answer support higher taxes on the rich, but very few people have the reverse set of preferences.

The good news is that nobody is really proposing any “special favors” for Black people. But Biden made his race-neutral small business relief program sound exactly like that, as did Pressley and Booker with their baby bonds bill. Why target the 3% while alienating the 31%?

Both cross-pressured quadrants are swing voters, but the populist quadrant has way more people in it. Below is that previous graph, now with voting behavior added. The C is for the share that voted for Clinton, T for Trump, and J for Gary Johnson.

If you want to win an election, you have to win swing voters. But you shouldn’t build a strategy around attracting woke capitalists at the expense of populist support.

The same pattern recurs

That question pairing is not unique. Here’s the same tax hikes question paired with a question about freewheeling expression versus avoiding offensive speech.

In this one, I rounded up the woke capitalists from 2.55% to 3% — there are actually fifteen times as many populists than there are woke capitalists.

The same pattern recurs with a question about police violence:

Or we can return to the racial resentment question and look at a different economic question:

Recall that because white people are on average richer than Black people, a more even distribution of resources will necessarily narrow racial gaps. But once again, simply sticking to the economics wins many more voters than adopting a racialized frame.

The pattern is the same for Black voters

There’s an argument that race-specific appeals are somehow critical for generating Black turnout. But even if you look only at Black voters, the same trend holds: There are far more populists than woke capitalists. Here’s the original chart, now just with Black people.

The Black electorate differs from the total population in that there are more liberals and fewer conservatives. But in terms of cross-pressured groups, it’s still the case that there are far more people in the top left box than the bottom right one.

And it’s the same for the political correctness question.

Specifically on turnout, when Priorities USA was testing messaging aimed at inspiring African American participation in the Alabama Senate race between Doug Jones and Roy Moore, they found the best ad was a pretty generic pitch about education.

Effective politicians know this

In 2020, Black voters propelled the least-woke candidate, Joe Biden, to a primary win after he struggled immensely in the first three states (none of which had large Black populations). The second most popular candidate among Black voters was the begrudgingly woke Bernie Sanders.

The 2020 Democratic field was obsessed with race, from Kamala Harris to Elizabeth Warren to Cory Booker, yet Black voters overwhelmingly chose the most deracialized campaigns instead.

Peak Black turnout came in the 2008 and 2012 campaigns. In his new book (here’s the excerpt), Barack Obama describes his explicit decision to avoid talking about race, even after the Tea Party surged amid quite visible displays of racism:

As time went on, though, it became hard to ignore some of the more troubling impulses driving the movement. As had been true at Palin rallies, reporters at Tea Party events caught attendees comparing me to animals or Hitler. Signs turned up showing me dressed like an African witch doctor with a bone through my nose. Conspiracy theories abounded: that my health-care bill would set up “death panels” to evaluate whether people deserved treatment, clearing the way for “government-encouraged euthanasia,” or that it would benefit illegal immigrants, in the service of my larger goal of flooding the country with welfare-dependent, reliably Democratic voters. The Tea Party also resurrected an old rumor from the campaign: that I was not only Muslim but had actually been born in Kenya, and was therefore constitutionally barred from serving as President. By September, the question of how much nativism and racism explained the Tea Party’s rise had become a major topic of debate on the cable shows—especially after the former President and lifelong Southerner Jimmy Carter offered up the opinion that the extreme vitriol directed toward me was at least in part spawned by racist views. At the White House, we made a point of not commenting on any of this—and not just because Axe had reams of data telling us that white voters, including many who supported me, reacted poorly to lectures about race. [emphasis mine]

Obviously having the first Black president on the ticket did a lot for turnout. But there’s just no real evidence that sporadic Black voters are looking for large amounts of explicit race talk.

To advance racial justice, you need to win

Again, it’s completely true that left-of-center economic programs advance racial equity.

But nearly all Democrats would continue to advocate for anti-poverty programs even if the poor were a perfectly racially representative group.

Racial issues are fashionable in progressive circles, so it’s useful in intra-progressive status competitions to say that your pet issue has a racial equity angle. But this approach risks losing many more cross-pressured voters than it has any chance of winning.

Whether you think people are skeptical of things that seem to help some races at the expense of others (this is my take), or if you think Americans are simply really racist (probably someone’s take), the conclusion is actually the same: if you want to advance racial justice, you have to win first. And you can’t win by alienating all the populists.

This was conventional wisdom until very recently. Obama knew focusing on race would hurt him, allowing him to be popular enough to win states like Indiana once and Florida, Ohio, and Iowa twice. Even back to the 1980s, you had William Julius Wilson writing stuff like this, referencing points made 25 years before that:

I am reminded of Bayard Rustin’s plea during the early 1960s that blacks ought to recognize the importance of fundamental economic reform (including a system of national economic planning along with new education, manpower, and public works programs to help reach full employment) and the need for a broad-based political coalition to achieve it. And since an effective coalition will in part depend upon how the issues are defined, it is imperative that the political message underline the need for economic and social reforms that benefit all groups in the United States, not just poor minorities.

So I don’t think this should be taboo to say: Americans, on average, are in line with (or even to the left of) Democrats on economics, but they are not in line with the Democrats’ new focus on making everything about race, including the very economic ideas that give them a fighting chance to win elections.

Pretty darn good article for an intern. I’m not white but I can say I feel a little bad when I hear how a certain program is going to target black, Native American, Hispanic, and other marginalized communities. I don’t feel bad because I sympathize with white supremacy or have anything but compassion for the plight of all sorts of minority groups, but because I’ve lived around a heck of a lot of white people who have struggled mightily. I work with people like that. Folks who’ve been on welfare or are the first in their family to go to college or have had abuse issues or any of a number of other difficult challenges. When u say for the thousandth time that we

need to target folks by race I know these people hear that they are not valued, because I hear them say it. They have not been floating around in clouds of white privilege. Maybe some people have, but they haven’t and why do we need to insult them? And why do we have to jump through all sorts of rhetorical hoops and disclaimers to say we support them? In short, I agree with the article Marc, nicely done.

Along these lines, let's retire the phrase "white privilege". We need a different name for the things that white people currently have a disproportionate share of, which we want all people to have access to. There are few white people in the 95% who sees themselves as privileged and the word privilege connotes something that can/should be taken away. There aren't many in the top 5% who see themselves that way either.