Do investor-owned single-family homes cause drug overdoses?

I mean, obviously, no they don't

In its new “populist” phase, the conservative movement is demonstrating a lot of the bizarre, intellectually sloppy anti-market paranoia that I used to associate with the political left.

As an element of the progressive coalition, that kind of thing was unfortunate, but it was at least associated with useful ideas like a welfare state to ensure that prosperity is broadly shared and regulation of pollution and other harmful externalities that are associated with profit-seeking businessmen. But in the hands of right-populists, it’s mostly nonsense. Former White House senior aide and leading GOP communicator Mercedes Schlapp, for example, was ranting last week about the “threat” to the country posed by Bill Gates “buying up the majority of American farmland” while BlackRock buys “the majority of single-family houses.”

Bill Gates does not own the majority of American farmland. I assume she meant to say something else, but the tweet remains uncorrected so who knows.

But the BlackRock thing is a bigger deal.

J.D. Vance has been warning of the threat of BlackRock buying single-family homes for over a year and alleges that “the Left will ignore this, because BlackRock has committed to ‘racial audits’ and other diversity BS.” Last week at an event, Vance incorporated this narrative into his pitch on the opioid abuse crisis. David Weigel reports that after explaining that BlackRock investing in SFHs is going to make it harder for Americans to live in owner-occupied housing, he offered this account of the opioid issue.

I want to be really clear about this: I do not have any easy solutions to the opioid problem, which is objectively very difficult. But I feel very confident that banning private equity companies from making investments in the housing market is also not a solution. Instead, Vance is offering us a glimpse of the dangerous world that will arise if the New Right moves beyond using culture war chum as an electoral strategy and starts using it as a substitute for policy analysis.

American farmland is broadly distributed

If you think about all the farms in America, the logistical aspects of Bill Gates — one guy! — buying up a majority of the land boggle the mind. Not that much farmland is even for sale at any given time.

There’s a niche publication for everything, including “The Land Report: The Magazine of the American Landowner,” and the most recent issue features a list of the largest landowners in America. Gates isn’t even number one on the list; the top landowner in America is a guy named Reed Emmerson who I’ve never heard of. He’s apparently a timber guy rather than a farm guy, but the fact that he’s not particularly famous underscores the reality that rural land is just not that big of a deal in the contemporary American economy.

Gates really is the number one owner of farmland in the United States, but he’s only 47th in terms of total acreage owned. According to Land Report, he has 242,000 acres of farmland and 268,984 acres of total land.

That’s a lot, but according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, there are about 915 million acres of farmland in the United States spread across more than two million farms.

The upshot is that Gates owns something like 0.026 percent of all farmland in the United States — really not a very large share. American farmland ownership is very un-concentrated. For comparison, Toyota has 12.2 percent of the global market share of the automobile industry, which is pretty competitive in the scheme of things.

It’s also worth saying that when Gates’ farm ownership became a big story in 2021, the total value of his agricultural land was estimated at $690 million. That’s a large number, but Gates’ net worth is $127 billion — a much larger number. Rather than asking why Gates is buying up all this farmland, a more interesting question might be, “Why is Bill Gates allocating 0.5 percent of his total investment portfolio to farmland?” In other words, it’s not even a particularly large investment; he’s just really rich. The two Americans who are richer than Gates, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, are more heavily invested in the companies they founded. Gates has been gone from Microsoft for a long time, so it makes sense that his portfolio is more diversified. In terms of a threat, there’s obviously nothing there.

Renting doesn’t cause opioid overdoses

There is more to life than cross-sectional comparisons, but whenever someone posits a theory about the causes of the opioid epidemic, I do think it is helpful to turn to a basic analysis of our state-by-state data.

Vance’s hypothesis is that BlackRock buying houses leads to a lower homeownership rate which leads to more despair which leads to opioid addiction and death. But I don’t see it.

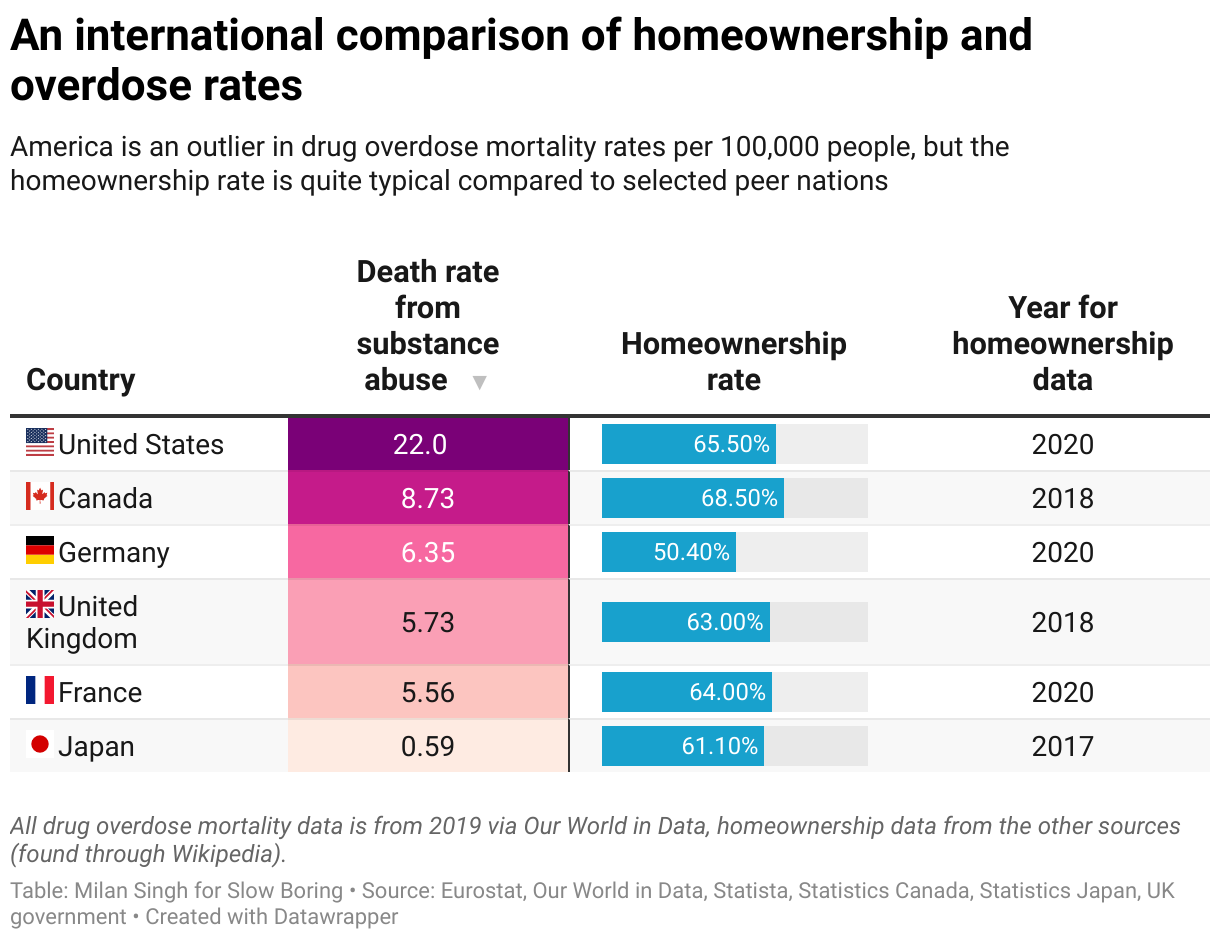

And in international terms, this hypothesis looks even more ridiculous. Germany has a much lower homeownership rate than the other G7 countries, but it doesn’t have staggeringly high levels of despair-induced opioid overdose.

I frankly dislike the whole “despair” theory of drug overdoses. Japan, for example, has one of the highest suicide rates of any rich country, which seems like a good indicator of the presence of a lot of despair. But they have very few drug overdose deaths.

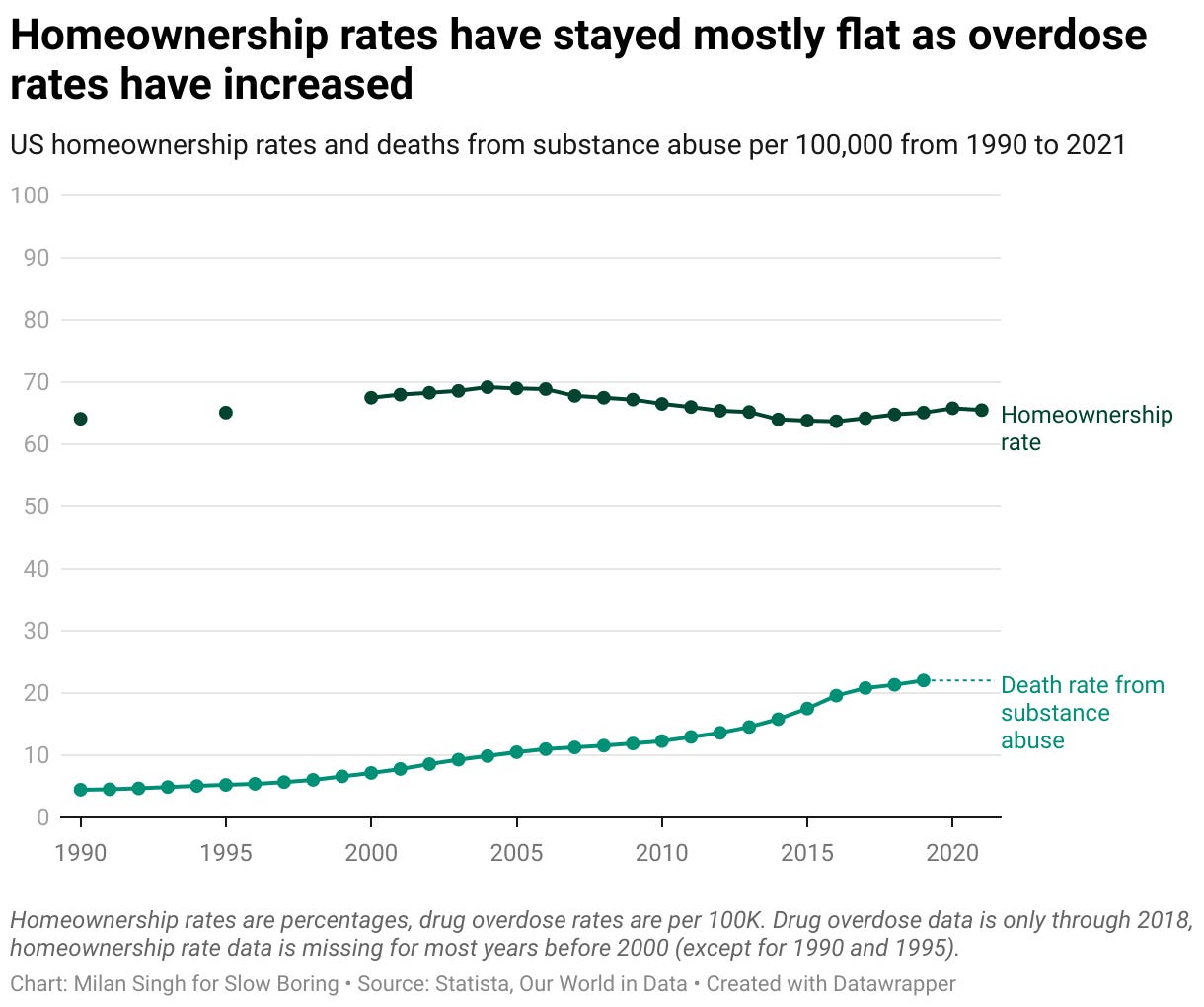

And while the homeownership rate was falling during the Great Recession as the opioid epidemic gathered steam, it started rising again in 2016 and opioid deaths just kept soaring.

Long story short, I think these things have basically nothing to do with each other.

Vance is correct to identify the drug overdose death toll as a major problem in American life, one that the political system has been failing to solve. If we could go back in time and have the FDA regulate OxyContin differently, that would be a great solution, but we can’t actually do that. And Vance’s political patron, Peter Thiel, doesn’t want the FDA to regulate things more strictly on a forward-looking basis, he wants the opposite. And Vance does not appear to have anything to contribute to our understanding of the opioid situation now that the OxyContin cat is long since out of the bag.

So he’s riffing about BlackRock — all vibes and no policy.

Private equity firms buying houses seems fine

If you ask people why they buy homes, they normally cite a few different reasons, often including the investment value. If you ask private equity companies why they buy stuff, the answer is that they are seeking good investments. So since houses are at least potentially good things to invest in, it seems reasonable that some investment firms might try to invest in them.

Is that bad? One argument for it being bad says that injecting more capital into the housing market raises prices. But that also means that homeowners, who are a majority of the population, are seeing their wealth go up. You could try to ban big investment firms from buying shares of stock in order to open up the doors to affordable stock ownership, but most people would think that’s a bad idea — it would depress the value of the stock market and ultimately depress investment in American business and business equipment.

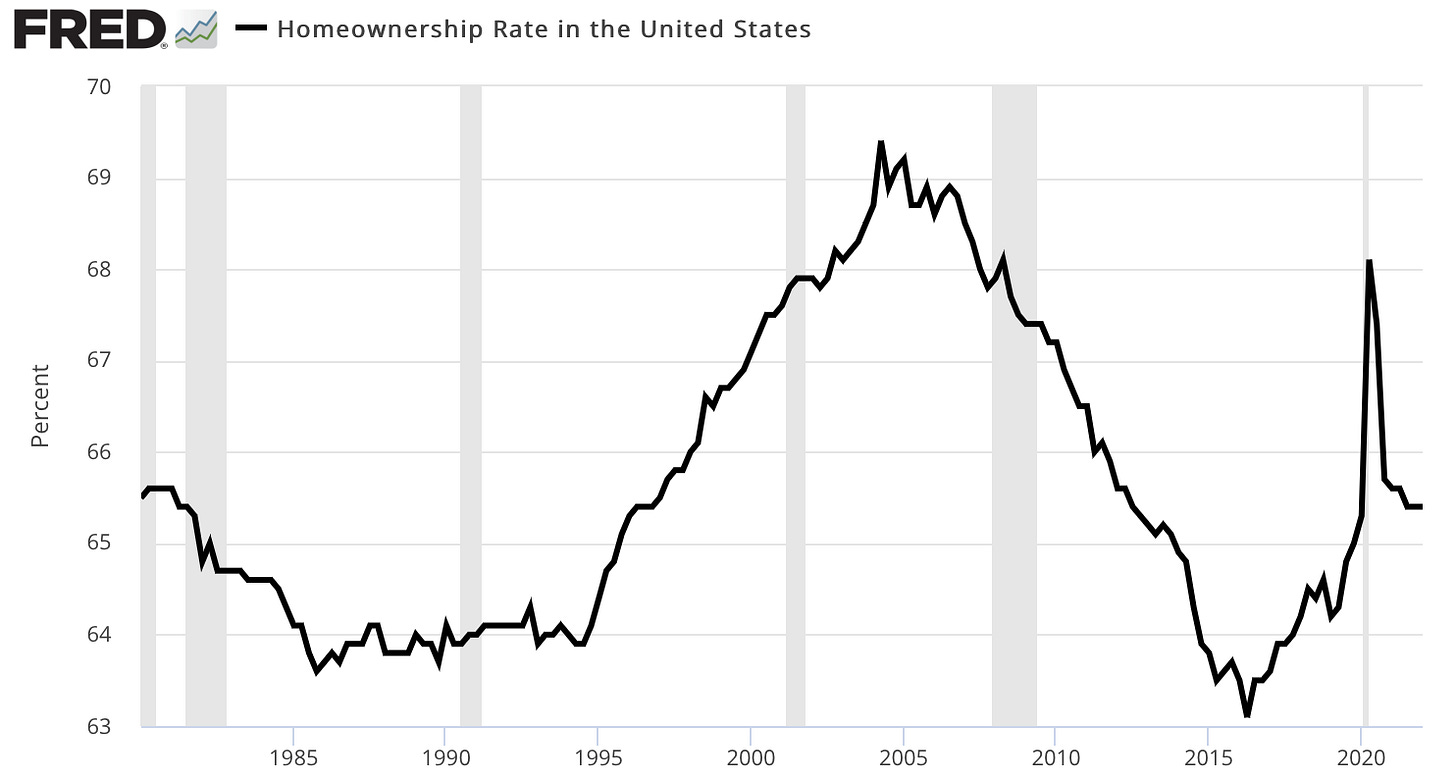

Are private equity firms making it impossible for people to buy homes? They don’t seem to be. The homeownership rate soared briefly during the pandemic and then crashed,1 but it remains at a higher level than it was pre-pandemic and a pretty normal level historically speaking.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.