Democrats should care less about demographics

The real lesson from the best analysis of the 2024 election

Every election night, politics fans start fretting over exit polls, and I always caution against taking the demographic analysis offered in those polls seriously, mostly for boring methodological reasons.

Figuring out how different sub-groups of the population voted is an annoying process that takes some time to complete in a rigorous way. Even once it’s done, a fair amount of uncertainty remains. Most informed people regard Catalist’s work on this as the best publicly available analysis, and if you want to know what’s up, you just have to wait for Catalist’s report.

Well, their report came out last week, and if you’re interested in what happened in 2024, reading “What Happened in 2024” is a great place to start. The report is unparalleled in its level of detail.1

But Catalist is in the business of producing demographic analysis of the electorate. That’s why they produce such excellent reports on demographic analysis of the electorate, reports that, naturally, make a big deal out of the demographic analysis. If you stare at them long enough and think about what they’re really saying, though, the message you should take away is that Democrats should probably reduce the amount of time they spend thinking about these demographic sub-slices.

Because what happened between 2020 and 2024 was a broad swing against Democrats.

It’s true that the swing was larger in some sub-sets of the population than in others, but that, in turn, basically comes down to the fact that people who were more impressionable were more likely to change their minds. The swing, in other words, happened among swing voters. These voters are mostly younger and less-engaged and disproportionately Hispanic. But it’s not like the swing only happened among young Hispanics and now Democrats now need to triple-down on understanding what young Hispanics think.

There are just not that many open-minded people in a polarized country — a lot of folks are very dug-in on Trump, either pro or con. People who are younger and people who pay less attention to the news are more open-minded, and the Latin population in the United States is much younger and less attentive to mainstream news than the Anglo population. Demographic targeting is important for certain micro elements of political strategy, but the macro picture is that Democrats did worse with all kinds of voters. And the key to doing better almost certainly won’t be found in micro strategies.

Two kinds of demographic targeting

I learned an important distinction recently from someone who has a lot of experience doing quantitative evaluation of different ads.

He told me that when you’re thinking about demographic targeting for your ads, it’s almost never the case that a certain topic or message does wildly better with white women or Hispanic men or whatever other sub-sample you’re looking at. Rather, different messengers perform differently.

So for example, this Future Forward ad featuring a Black guy talking about how Trump coddles billionaires might be more persuasive to an African-American audience, while this other Future Forward ad featuring a white guy talking about how Trump coddles billionaires could work better with white audiences. But the semantic content of the ads is quite similar, because messages about tax fairness were broadly effective.

That’s basically a boring marketing take, like how with a sufficiently large budget, a company might alter the demographics of the family in their toothpaste ad based on the anticipated audience. And obviously, if you’re managing the ad spend for a super PAC, it’s in your interest to take this kind of thing seriously. You want ads in Spanish for a Spanish-dominant audience. You want ads featuring good matches for the ethnicity, gender, and age of your audiences. You want to match messengers with audience in ways that maximize impact.

But often, people are looking to demographic analysis for some deeper political insight, not marketing strategy.

Around a decade ago, Democrats decided that it was really important to talk to Hispanic audiences about immigration and to Black audiences about criminal justice reform. That style of thinking led a wide group of people working in public policy and in politics to emphasize demographic analysis — to really understand how to do politics, you had to understand the nuanced views of young people of color versus middle-aged white people, beyond the broad insight that the former are more progressive than the latter.

And we do sometimes see elections with contrasting demographic swings.

In 2016, for example, Trump really did do a lot worse than Mitt Romney with Hispanics and with college educated women, while also doing dramatically better with secular non-college whites. You cannot summarize that election as “Well, Trump was more popular than Romney so he did better overall.” He did do better overall, but there were notable pockets where he did a lot worse that were offset by doing better with a larger pocket.

But that was an exceptional election, and it’s a mistake to anticipate that a political generalist should invest in this kind of demographic targeting as a rule.

What happened in 2024?

We naturally tend to pay more attention to things that are interesting rather than to things that are boring. But for my money, the two most important charts in the Catalist report are two of the most boring ones. This one shows that though the gender gap increased, Kamala Harris did worse with both men and women — including Black women — in 2024 than Joe Biden did in 2020.

Similarly, while support for Democrats declined notably among the youngest voters, there was broad decline across generations.

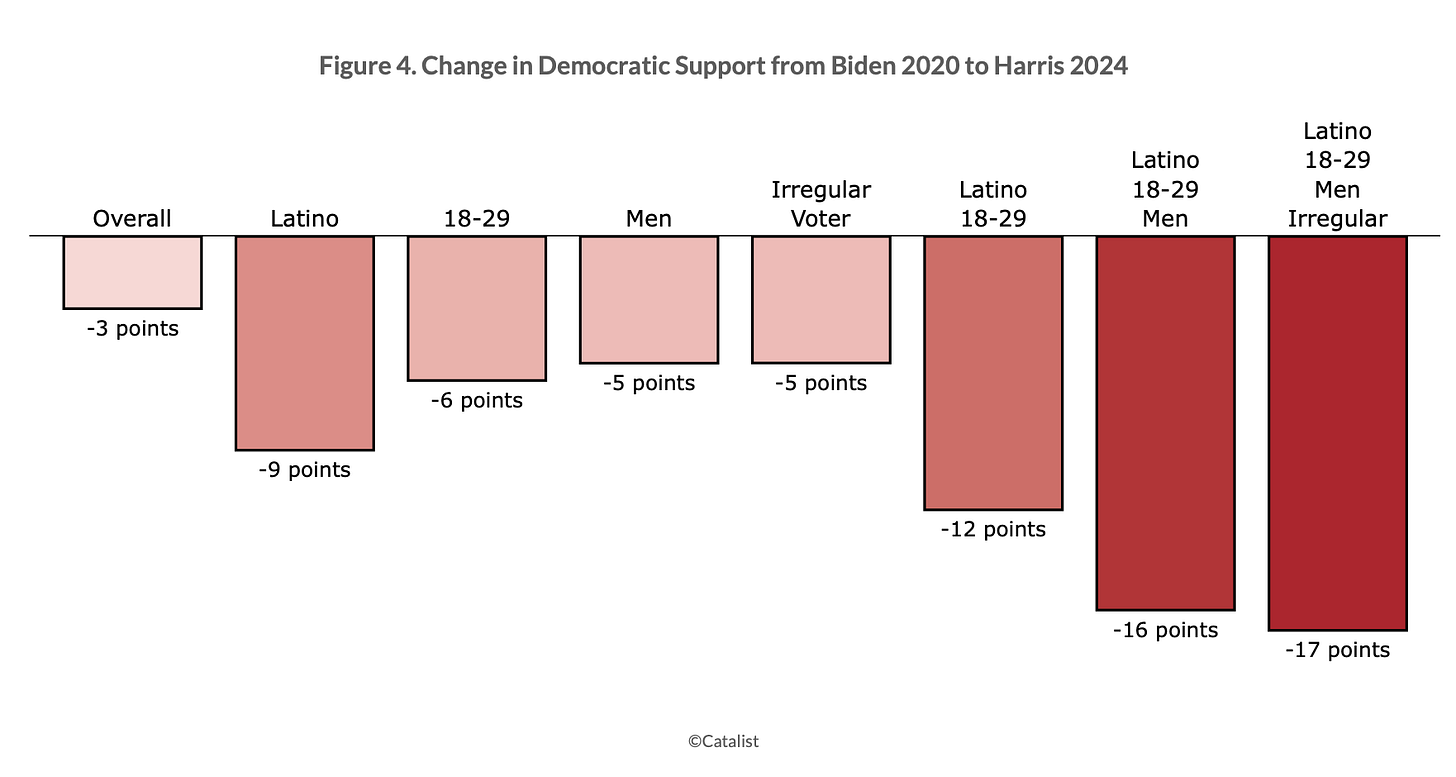

Of course, if you slice the salami thin enough, you can generate exceptions. I have seen some evidence that Harris did better than Biden with older white women, which is consistent with the buckets that we have here. And the non-boring headline conclusion that Harris did terribly with young Hispanic men, particularly the ones who are irregular voters, is certainly striking.

But even here, I think the most important point to make about this finding is the one Catalist itself makes in the text — do not over interpret the demographic slices, because you’re looking at a lot of overlap:

Importantly, it would be a mistake to consider these demographic attributes one at a time. For instance, Latinos are more likely to be irregular voters than white voters, young people are less likely to vote in midterm elections, and Latinos are more likely to be young. In other words, these groups overlap considerably. Further, groups that had a combination of these traits were more likely to move away from Harris. Among young Latinos, Harris lost 12 points; among young Latino men, 16 points; among young Latino men who are irregular voters, 17 points. Similar trends are evident across other combinations of these groups and sub-groups, including along racial, gender, age and vote history lines.

The upshot, again, is that to a first approximation, there was a broad swing against the Democrats. People were upset about inflation and about immigration, they had a particularly negative assessment of Joe Biden, and the candidate swap helped a lot but not enough. I have my own theories of how the swap could have been handled better and what Harris could have said differently, but I don’t want to grind those axes again.

The point I want to make is that even though the declines were concentrated among younger voters and disengaged voters, there’s no reason to think that micro-targeted appeals to young disengaged Latino men were the key here. The backlash was broad-based (and, as many people have noted, it afflicted incumbent parties everywhere). What we see in the demographic slices is just the kinds of people who were unusually amenable to changing their minds.

To give an example, most of the people I know think that Donald Trump did a really terrible job with Covid and that Joe Biden greatly improved things once he took over.

If this were a majority view, Trump would have lost. I’m with the group who judged Trump’s performance harshly at the time, but was then disappointed to see Biden make mistakes in the other direction. But because I’m a 44 year-old professional journalist with lots of deeply held opinions about public policy issues, I don’t switch my partisan preferences just because I’m annoyed. A 23 year-old who doesn’t really follow politics is either not going to vote, or else he’s going to be heavily swayed by events like this. To the extent that there’s a lesson here, it isn’t anything about 23 year-olds or people who don’t follow the news, it’s just that you should try to make decisions that make people happy. Or that if you’re going to dump your unpopular candidate, you should swap in someone who has more distance from him.

Politics is boring

Equis Research does the best work helping Democrats understand Hispanic public opinion, and their new report focusing on how this has evolved since Inauguration Day is good.

But to the extent that I have any criticism of their work, it’s that because the whole business model is focusing on Hispanic public opinion, it’s sort of in their interest to downplay how banal the relevant dynamics were this election.

It turns out that the group of low-information voters who swung heavily toward Trump because they were angry about the economy is now mad at Trump, because they are still angry about the economy. It’s true, factually, that “young people who don’t follow politics closely” is a much more Hispanic slice of the population than the national average. Or alternatively, it’s true that the Hispanic population contains a large fraction of young people who don’t follow politics closely. But either way, the people at issue are not responding to events in a distinctively Hispanic way. They are responding to events like people who lack strong partisan attachments or deep interest in the issues and just care a lot about whether the economy seems to be doing well.

Similarly, in the Equis poll, Latinos think Trump has gone too far on immigration but many have relatively conservative views on some aspects of immigration policy.

For example, when asked about the most important aspect of immigration for Congress to focus on, 33 percent say protecting law-abiding immigrants from deportation and 13 percent say defending the asylum process. But a larger group chose tightening border security (26 percent), closing it altogether (12 percent) or “supporting president Trump’s efforts to deport immigrants that are in the U.S. illegally” (12 percent). A majority of Hispanics agree that “immigrants and asylum seekers who arrived recently unfairly receive benefits while American citizens and immigrants who have been here a long time are neglected.” Overwhelming majorities want to deport violent criminals. And these hawkish views sit alongside a lot of practical reluctance to deport people who’ve been living here and haven’t committed crimes.

These are good things to know, but they basically confirm that Hispanic public opinion has the same contours as everyone else’s — concern about border security, about migrant crime, and about immigrants competing for welfare state resources, paired with sympathy for deserving cases. Also, the share of Hispanics citing immigration as a key issue is only 17 percent, with 40 percent saying either “cost of living and inflation” or “economy and jobs.”

All sub-groups have some marginal voters

That’s a lot of words to say that you don’t need to pay attention to this, but I do think it’s important for Democrats to rid themselves of the habit of thinking of the country as composed of demographic slices.

Most voters care a lot about their personal material prosperity and are looking for strong performance on this from incumbents and good messages on it from opposition figures.

Demographic analysis is pretty important if you’re literally making ads or deciding which ads should be placed where. But the thing that gets lost in much of this analysis is that while different blocs of voters are different on average, every group contains some marginal people.

In other words, if you look at a group of non-college white men, the average is going to be a pretty hardcore Republican. And if you look at a group of African-American women, the average is going to be a pretty hardcore Democrat. But there are non-college white male Democrats and (a smaller number of) Black female Republicans. And in both groups, there are some people who are having trouble making up their minds. And these marginal voters mostly have the same bundle of contradictory impulses, regardless of their demographic qualities:

Want to see spending cut, but are pretty supportive of almost every major actual spending program

Worried about climate change, but don’t want to make any personal sacrifices to address it

Think the rich should pay higher taxes, but no matter how rich they are, they think “the rich” means someone richer

Believe the system is broken and we need major change, but in practice are incredibly change averse

You know the type. This is the electorate in all its contradictory glory. People disagree about how best to appeal to this kind of cross-pressured voter, and while I have a view on that, I don’t want to grind the axe here. But what I do want Democrats to take more seriously going forward is the fact that cross-pressured people exist in all demographic categories. A sound political strategy is going to address them broadly rather than in micro-detail and recognize that understanding the average attributes of different demographic blocs isn’t actually informative about the views of the marginal members.

The Blue Rose data that David Shor presented on the Ezra Klein Show a few months ago is somewhat different in its specifics, but broadly aligns with Catalist’s top line conclusions.

It's a banal observation, but focusing solely on minority demographic groups is not a winning strategy in a democracy, because they are not a majority. And minority groups cannot be added together to create a majority, because as the Catalist report makes clear, many people in different minority demographic groups overlap.

"Joe Biden greatly improved [Covid] things once he took over."

One (not the only) ways that Biden disappointed was that he did NOT dramatically improve on Trump's handling except for not having those ridiculous press conferences. Did CDC finally start giving individuals and public policy makers information to make better more cost effective decisions? Did retaining international travel restrictions and testing to fly make any sense by then if ever? If Biden really DID do something better why wasn't it mentioned in the campaign?