Democrats can't hide from immigration forever

An approach to openness that serves the national interest

My number-one mixed-feelings issue is immigration, where I recognize that I am someone whose sincerely held convictions on a hot-button policy topic are far out of line with public opinion.

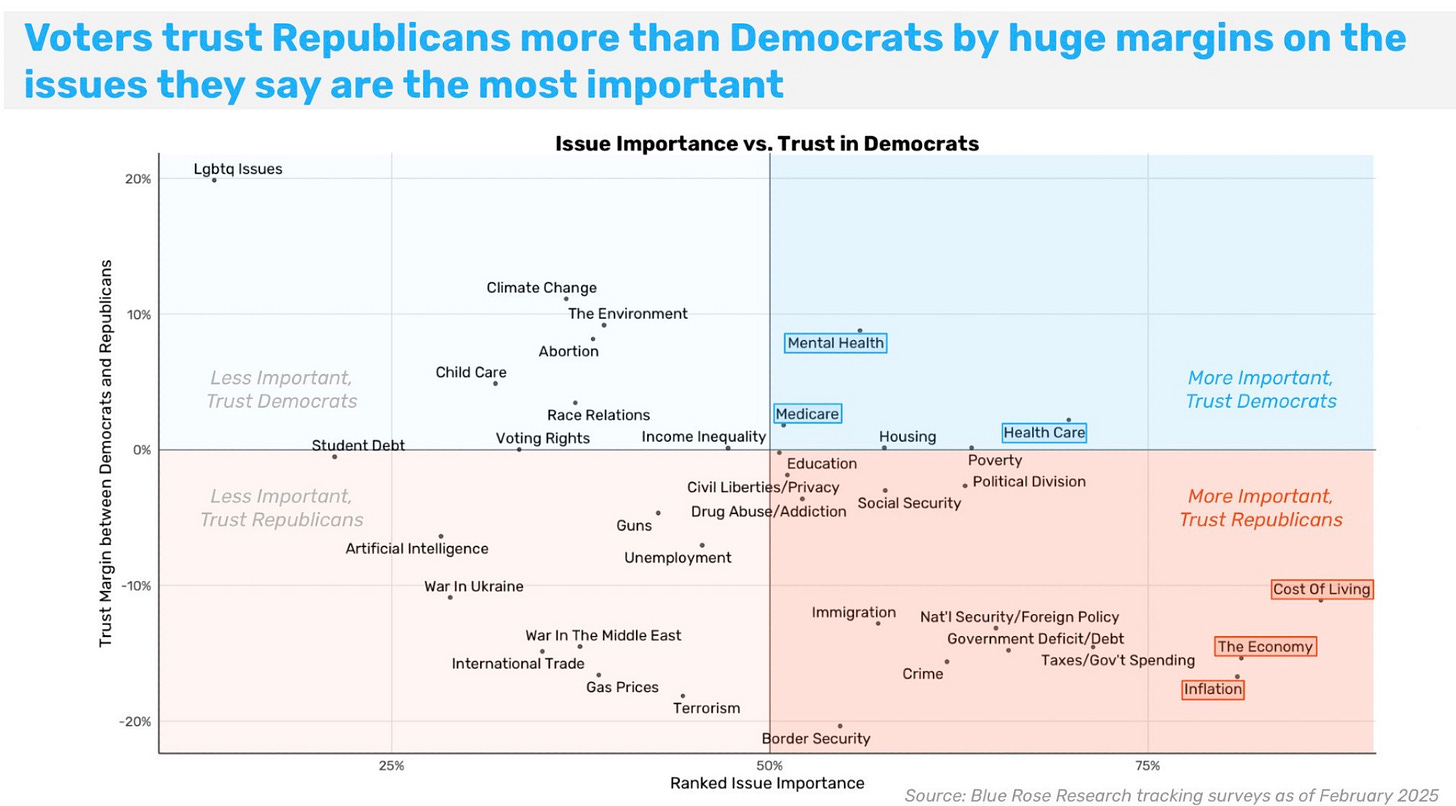

Even with Trump’s approval rating sliding in the face of a falling stock market and a general backlash to the administration’s many instances of overreach, his numbers on immigration remain strong. Immigration policy is the topic on which Republicans enjoy the largest trust advantage.

Trump’s big edge on issues related to the economy and inflation is likely to fade in response to his actual governance, and I think Democrats can reposition themselves in a number of ways there, including many that I personally agree with.

On immigration, though … it’s tough.

I warned after just two months in office that Biden was losing the plot on asylum and the border. If you scour the text of One Billion Americans, you’ll find that I am often bending over backwards to endorse strong border security, tougher enforcement measures, and selectivity in immigration — I’ve always been well-aware of the political risks involved in an immigration policy that just amounted to backing off on enforcement. That said, I wrote One Billion Americans because I believe, very strongly, in the productive power of immigration. I wrote this whole bizarre alternate history of Gilded Age politics recently, in part, because I think that Trump is importantly wrong about the tariff and immigration debates between Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison. I’ve long been a fan of a paper Doug Irwin published back in 2000 (when free trade was conservative-coded and immigration was largely non-partisan) showing that 19th Century tariffs did little to promote industrialization and that the actual key driver was “population expansion and capital accumulation.”

But I think that the average person badly underrates the long-term economic benefits of migration because of Malthusian intuitions that are deeply embedded for evolutionary reasons and don’t really stand up to scrutiny. And while I don’t think it makes a ton of sense on the merits to talk about “abundance” as a concept without talking about immigration, I also appreciate that as an intervention in factional controversies, it makes a lot more sense to duck the issue.

Indeed, for all the intra-party bitterness right now, all factions of Democrats seem largely aligned on this.

If you ask the most chickenshit moderates and frontliners, they want Democrats to focus on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. And if you tune in to Bernie Sanders’s “resist oligarchy” rallies, he’s focusing on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. This is not to say that Democrats have been categorically silent. There’s been pushback to ending Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelans (trying to appeal to traditionally conservative Cuban-Americans and other anti-Communist Hispanics). Hakeem Jeffries reiterated Democrats’ commitment to protecting Dreamers, while arguing that mass deportation could cause economic harm at a briefing organized by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ). Still, even in the context of that NAHJ event, Democrats were trying to put more emphasis on Medicaid.

“Run for the hills” is a reasonable tactical response to the vicissitudes of the moment, and Jeffries’s instinct to tell NAHJ about Medicaid is a positive sign that Democrats have moved away from thinking that immigration policy is the key to winning Hispanic votes.

But even on issues you’d rather not talk about, you’re eventually going to need to say something. And, of course, if Democrats win, they’re going to have to govern.

What Trump is doing

In quantitative terms, the biggest thing that Trump has done since taking office is intensify the trend that Joe Biden started with his June 2024 asylum crackdown. Biden’s orders came on the heels of successful diplomatic efforts to get Mexico to intensify its interdiction efforts. And that combination of changed executive policies plus pressure on Mexico was working, perhaps given a boost by a cooling of the labor market in the United States.

Under Trump, labor market cooling has continued, so “pull” factors are weaker than ever, and Trump has increased the intensity of enforcement by sending more active duty troops to the border region. He has also leveraged the fact that these policies are working to revoke a major Biden humanitarian parole program for people from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

This CHNV program allowed up to 30,000 individuals per month from those four countries to enter the US legally and stay for up to two years, as long as they had an American sponsor. The rationale for CHNV was largely political. Since the Cold War, the US has given would-be emigrants from Cuba special treatment, and there’s a longstanding push from the Congressional Black Caucus for equal treatment of Haitians and Cubans in the name of racial equity. And Nicaragua and Venezuela have Cuba-aligned socialist regimes, and those communities in the US are integrated with the Cuban emigré community. But the policy rationale for CHNV is that creating orderly, legal pathways reduces irregular migration and pressure at the border. Biden was trying to narrowly solve for border chaos and CHNV helped.

Trump’s team loves to make political hay out of border chaos, but they also very sincerely want less immigration, so for them it’s not, “CHNV is good because it helps relieve pressure at the border,” it’s, “Deterrence is all you really need and we’re scrapping this because we want fewer immigrants.”

The deterrence strategy isn’t just border enforcement, though. Trump has made reducing migration his administration’s top diplomatic and economic priority when engaging with all Latin American countries.1 And if he just left it at that, he would probably notch a huge political win — “I secured the border” — and Democrats wouldn’t necessarily need a response beyond throwing Biden under the bus for being so slow to react to the breakdown of the asylum system.

But Trump keeps pushing the envelope in alarming ways:

We’ve had weeks-long lockups of European tourists who were crossing the US-Mexico border.

The administration is deporting alleged members of the Tren de Aragua gang with zero due process, perhaps on evidence as flimsy as a Real Madrid tattoo.

They are seeking to deport lawful permanent residents for constitutionally protected speech.

A Mescalero Apache tribe member was questioned in New Mexico and asked by ICE to show his passport.

And, of course, we have the ongoing litigation over birthright citizenship.

Some of this explains how questions related to interior enforcement became a policy priority for Hispanic-origin American citizens: People with Spanish names (just hypothetically), especially those who have darker skin or who speak English with an accent (or who have close family members who do), are the people who are most likely to be profiled or wrongly detained in the sort of undisciplined crackdown Trump has begun. And in addition to the impacts on the people and families who are experiencing this directly, the administration risks crippling American tourism, making American universities undesirable places to study, and breaking the virtuous cycle in which the most talented tech entrepreneurs and workers from the non-Chinese world want to move here.

Notably, though, Trump has not yet stepped up workplace raids or sanctions on employers, even though there was lots of buzz about this during the transition.

Back to the future

Here’s something that Ezra Klein wrote in October 2021 and that I think is important for everyone who cares about immigration to consider:

David Simas, the director of opinion research on Obama’s 2012 campaign, recalled a focus group of non-college, undecided white women on immigration. It was a 90-minute discussion, and the Obama campaign made all its best arguments. Then they went around the table. Just hearing about the issue pushed the women toward Mitt Romney. The same process then played out in reverse with shipping jobs overseas. Even when all of Romney’s best arguments were made, the issue itself pushed the women toward Obama. The lesson the Obama team took from that was simple: Don’t talk about immigration.

This is why, when it comes to immigration, many of the Trump administration’s most egregious excesses are going to be fought primarily through litigation rather than vocal politics.

It’s also important to remember what happened after Obama successfully ran this “don’t talk about immigration” reelection campaign — his team went out and told reporters that Democrats had won thanks to Hispanic backlash against Romney’s self-deportation rhetoric. The RNC then did an “autopsy” report on the election that concluded that Republicans needed to move to the center on immigration. And an immigration reform bill including a path to citizenship for millions of undocumented residents passed the Senate with overwhelming bipartisan support.

Which is just to say that as far as I can tell, the Obama team fibbed about the role that immigration played in the 2012 campaign as part of a strategy to psyche Republicans into agreeing to an immigration deal — and it almost worked!

Unfortunately, one of the problems with lying in politics is that while you sometimes trick your opponents, you are much more likely to trick your own supporters. The Gang of 8 bill that Obama was trying to get done was good legislation and I wish it had happened, so I can’t criticize the team too harshly for trying their best. But the ultimate legacy here was to mislead Democrats about the actual politics, which isn’t that voters hate all immigrants or want to see immigration ended, but is that people worry a lot about the downsides of being too lax. And unfortunately for Democrats, the advocacy groups they outsourced their immigration policy thinking to are very anchored in the community of immigration lawyers and in broad progressive skepticism of law enforcement. It’s not just that those voices can push fairly extreme positions, it’s that they don’t really have a coherent account of why immigration is good that is persuasive to most American voters.

Immigration in the national interest

People who immigrate to the United States of America obtain large benefits by doing so, and I am deeply sympathetic to the vast majority of the many, many people who would like to do this. All of my great-grandparents moved to this country at a time before the imposition of numerical quotas on the places they were coming from, and I feel incredibly fortunate for that. None of them were “highly skilled” in the contemporary sense or superstars in any particular field of endeavor.

I also believe that, precisely because immigration is so valuable, it’s important to be realistic about what’s politically possible here. Simply throwing sand in the gears of enforcement is not a viable strategy.

Due process for immigrants facing detention or deportation is important in part because it’s a safeguard for American citizens. By the same token, one reason to support immigration is that immigration is (on average) good for American citizens. An affirmative agenda on immigration should aim to tweak the system to make it more beneficial to American citizens, understanding that the better you can make immigration for America, the stronger the case for more immigration. That means strong borders, it means deporting people who actually do commit crimes, and it means to an extent “building a wall around the welfare state” to make sure that immigration is fiscally beneficial for the United States.

The 2012 Democratic Party platform called for “comprehensive immigration reform that brings undocumented immigrants out of the shadows and requires them to get right with the law, learn English, and pay taxes in order to get on a path to earn citizenship,” emphasizing the fiscal benefits of taking a non-deportation approach to people who have been living and working here for a long time without committing non-immigration crimes. That version of the party also talked about the need to “hold employers accountable for whom they hire” — the immigration enforcement measure that Republicans refuse to take. I think Democrats today could also start talking about making it easier for companies to get visas to bring highly paid workers over and for foreign-trained doctors and dentists to come and practice in the US. An idea I keep floating is a small bump in employer-side payroll taxes for foreign-born workers to help keep Social Security solvent.

I think it’s important to take Simas’s lessons from the 2012 campaign seriously and recognize that all things considered, even the best immigration arguments probably aren’t big winners.

But politicians still need to have policy ideas they can explain when directly asked and a blueprint for how to govern the country. Shining a light on the most egregious instances of Trump’s cruelty in enforcement is important, but if that’s all Democrats do, they’ll end up with an immigration policy that amounts to “do less enforcement,” which doesn’t really work. We need to start with the premise that economic growth is good, that good immigration policy can contribute to economic growth if approached with an empirical spirit rather than cultural panic, and come up with ideas that facilitate that.

When Susan Rice, a former UN Ambassador and National Security Advisor, was somewhat oddly tapped to run Biden’s Domestic Policy Council, I thought this was what was going to happen. Why would you put a career foreign policy person in charge of the DPC? Well, the DPC runs immigration policy. If you plan to confront immigration policy primarily by externalizing enforcement, it might be smart to put a foreign policy person in charge. This forecast was not correct, and I don’t really know what happened.

Matt writes: "That means strong borders, it means deporting people who actually do commit crimes..."

My one (and relatively small) point of disagreement with Matt on this topic -- he is broadly right in his advocacy for increased immigration -- is this: If one wants "strong borders", presumably that is to keep out people who are attempting to enter illegally. So, why limit deportation to those who "actually do commit crimes"?

This rhetorically sounds to me like illegal immigration isn't a crime and isn't subjected to deportation. It is fuel for the view that we want open borders.

Our stance should be: Strong Borders, Deport Illegal Immigrants, Increase Legal Immigration Pathways.

Immigration is one of those Slow Boring hot-button issues, and at a certain level I think it's one of those ultimately irreconcilable topics because of psychological and emotional preferences.

I'm always cautious with work in political psychology, because doing good surveys is hard, but it does seem to be the case that people are roughly broken down between between a preference for sameness and a preference for difference. I'm not saying one is better - I know which one I prefer, but that is me and my preference doesn't really matter.

Being a political geographer, though, I would argue that if we're being honest with ourselves, technocratic details about immigration don't matter at a certain point. I agree that nailing the politics of immigration preferences - the topic of this essay - is essential for Democrats in the short term, but taking a step back, the notion of bounded political community that confers privileges on insiders and restrictions on outsiders relies on boundaries that are ultimately arbitrary. Deciding where those boundaries lie is inherently political - there is nothing natural or eternal or transcendent about them (on this point I disagree with e.g. Damon Linker, who wants to argue based on e.g. Isaiah Berlin that national communities have moral ontological status).

As is often the case, I'm not really sure what I'm trying to say other than that it strikes me that a lot of the debates that play out here over immigration seem to be more resistant to data-driven explanation and rely on prior beliefs and preferences more than is the case for other topics (big exception: trans issues, which is the ultimate "yell at each other" topic), and I think that's inherent to the topic itself.