America needs clearer goals on migration

More channels for legal immigration and temporary work should be part of the answer

I wrote a while ago about the virtue of policies that do exactly what they say on the tin — where the means and ends are clearly connected in an easy-to-understand way.

And it seems to me that if you want to understand the Biden administration’s struggles with asylum-seekers on the southern border, you have to understand it primarily in those terms — they have failed to establish clear goals. The White House’s viewpoint is that the media is being unfair to them, and I think there’s merit in that. ABC sending its entire Sunday show roundtable panel down to South Texas is an irresponsible effort to sow panic. In general, this is a tempting issue for journalists because they can be mean to Joe Biden (thus demonstrating independence and balance after they were accused of being too anti-Trump), but they can accomplish that in part by hitting Biden from the left, accusing him of having children detained in bad conditions, etc.

The flip side is that from Biden’s point of view, he is trying to balance a number of considerations, and that’s why nobody’s entirely happy.

And that’s fine as far as it goes. But it’s also a little question-begging. The policy largely seems to be designed to mollify various critics, which in turn is why nobody is happy with it. What is the actual desired end-goal here? I think ultimately, to have a politically sustainable approach, the goal needs to be something like “strict enforcement plus more legal migration through formal channels.” The effort to simply ease up a bit on enforcement and hope for the best isn’t going to stick.

Trump’s agenda: No asylum

Consider Donald Trump, who also struggled both substantively and politically with this issue.

One thing he had going for him is that his policy always had a fairly clear lodestar — he did not want people obtaining asylum in the United States. Because his goal was no asylum, his desired number of Central Americans making their way to the border to seek asylum was also zero. As a candidate, he seemed to believe that constructing a physical barrier between the US and Mexico would be a huge help here, but once in office that proved to not really be the case.

Eventually, he started “metering” people at the legal ports of entry so folks from Central America could not enter U.S. soil and make asylum claims. But that just left them wading across rivers, etc., so they came up with the idea of “zero tolerance.”

If you and your family crossed the border without papers, you’d be prosecuted. Since people being prosecuted go to jail, and since kids don’t get sent to jail just because their parents are being prosecuted, that ended up being the policy of family separation. Kids ripped from their mother’s arms in a deliberate effort to be cruel and scare people off from coming. That prompted a large political backlash, because normal people take a dim view of the deliberate infliction of cruelty on children. Trump had to back down. But because the Trump administration had a clear goal in mind, they were able to reboot the process.

I recommend Nicole Narea’s explainer on this for Vox if you want a detailed view, but the main story is that Trump largely externalized the process of halting asylum seekers.

Starting with Guatemala and then continuing with Honduras and finally El Salvador, Trump made diplomatic agreements with the three Northern Triangle countries that they would accept deportees from the United States. He also got Mexico to cooperate with his “remain in Mexico” initiative, in which the point was to prevent people from being physically present in the United States.

I’m not sure these particular agreements would have been fully stable over the longer term. But the point is that if you sincerely don’t care whether or not legitimate asylum claims are held, and you’re willing to make choking-off the flow of asylum seekers a diplomatic priority, there’s plenty you can accomplish. The same voters who recoil at cruelty afflicted in our names by our border agents are simply not as outraged by people suffering cruelly at the hands of gangs back home or the Mexican government. If Trump had been a savvier politician and frontloaded the idea of externalization from the start, it’s conceivable to me that he could have sold this as a successful regional strategy. Because he first covered himself with the moral stain of child separations, a fair number of semi-attentive progressives got semi-invested in this topic in a way that led Biden to unravel it.

Not Biden’s agenda: Welcome migrants

Erika Andiola, a longtime immigration activist and former Bernie Sanders operative, laid out the idea that Biden should do the opposite and welcome those seeking refuge here.

This is why conservatives have gotten increasingly comfortable describing the progressive position on immigration as “open borders.”

Nobody in the Democratic Party coalition has an Open Borders Act of 2021 or a formal plan to eliminate all immigration restrictions. But there is a broad discomfort with treating unauthorized migrants as criminals — up to and including several 2020 primary contenders vowing to decriminalize unauthorized immigration into the United States.

The problem with this approach and the reason the White House won’t adopt it as a goal is that “people seeking asylum (including children)” is not a fixed stock of people. The United States could easily welcome the several thousand people now in detention and would benefit from them settling to live and work in this country. But if thousands of people were willing to make a difficult and dangerous journey under the present circumstances, many more people might come if we were more deliberately welcoming.

Biden’s plan: Fix Central America

People immigrate to the United States from Canada all the time. But the life of an undocumented immigrant living in this country without a proper visa is really hard and difficult. So even though the U.S.-Canada border is not particularly hardened, people don’t really sneak into the country from Canada because Canada itself is a stable and prosperous country.

The Biden strategy, as articulated in his campaign, is not exactly to turn Central America into Canada. But it is to make things nice enough that people don’t feel the need to flee.

The plan has more detail behind the bullet points, and you can read all about it here.

I don’t really have a big take on whether this plan will work, other than the basic observation that addressing endemic corruption, rampant gang violence, and widespread poverty sounds really hard.

The main thing about this is that it’s a decidedly long-term strategy. Even on very optimistic assessments, a comprehensive four-year, $4 billion regional strategy is not going to address migration this spring.

So you’re still left with the question, do you welcome migrants or do you try to deter them? In theory, you could combine aspects of Trumpian cruelty with a humane approach to the regional development challenge. But as Senator John Cornyn put it while criticizing Obama, the administration has preferred to attempt to be humane.

And indeed, this was Biden’s promise; he vowed to “immediately do away with the Trump Administration’s draconian immigration policies and galvanize international action to address the poverty and insecurity driving migrants from the Northern Triangle to the United States.”

But this has left him in a little bit of a dead zone, with his officials now going out on camera to emphasize that the new more humane situation is still pretty harsh.

As a parent and just as a human being, I think it is hard to fault the Biden administration for trying to reduce cruelty to children. And since both Republican members of Congress and prominent TV journalists seem to want to make this the main issue of political debate, I would really urge reporters to ask Republicans if they want to go on the record as saying we should inflict more cruelty on children as a deterrent. I think anyone with a basic sense of morality ought to acknowledge that this is a bit of a tough problem.

The problem in terms of “what it says on the tin” is that I think Biden wanted to get a lot of credit for cruelty reduction without wanting to see a large rise in asylum claims.

My Weeds cohost Dara Lind always emphasizes that it’s a mistake to assume we know exactly how to connect the dots between U.S. policy changes and what people in Central America are hearing. But I think we know that in terms of domestic communications, Biden did try to signal a big break with Trump, even though I think he actually only intended a small one. The policy objective from both presidents is that asylum-seekers shouldn’t come here — with Biden trying to be a bit more humane about it, but not fundamentally eager to open the doors.

Externalization 2.0

To that end, I think the most striking Biden administration decisions on the migration front have been his foreign policy calls.

Back on February 6 when there was not a lot of attention being paid to this story, Biden rescinded the Trump-era “safe third country” agreements with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

Under the terms of those deals, you were obligated to seek refuge closer to home rather than in the United States if you said you were fleeing your home country due to persecution. The U.S. could thus reject your asylum claim promptly, and send you back to Central America. These deals were not operating in practice when Biden took over, because everything had been superseded by CDC orders related to COVID-19 that Biden didn’t revoke. So it was purely gestural politics. Biden could have said he was putting those agreements under review. Or that he planned to tweak them sometime in the future when the Secretary of State was able to visit the region. Or after a summit of Central American leaders that he would host in the states. But instead, they made a show of tearing them up.

But at the end of the day, the line between the strategy Trump settled on (coerce regional governments into making deals that block people from seeking asylum) and the Biden strategy (generous aid and regional development) can get a little blurry. In both cases, the policy goal is to externalize the problem. You don’t want people in harsh conditions in U.S. facilities, but you also don’t want them to come.

And indeed late last week, in what officials in both the U.S. and Mexico insist is not a deal, the Biden administration said it would send surplus COVID-19 vaccines to Mexico, and the Mexican government promised to be more cooperative on the asylum issue.

I don’t think it is that hard to imagine this relationship evolving in the direction of a regional strategy of essentially paying Mexico to do our dirty work for us. You wouldn’t call it that, obviously. But Mexico surely doesn’t find it desirable to have migrants traversing their country en route to the U.S. border. And if the arrival of migrants reliably puts Biden in a damned if you do, damned if you don’t situation, then it’s worth it to him to be generous with Mexico to avoid that dilemma.

Immigrants are really good

To me, the unending tragedy of this is that we are perennially stuck debating policy around asylum-claimants and illegal immigration when what we should be doing is increasing legal immigration.

Central Americans with low levels of education are not the strongest candidates for U.S. permanent residency in an expansion scenario. But as Michael Clemens and Kate Gough write, the United States would benefit from an expanded but less exploitative version of the H2A agricultural worker visa program.

Less exploitative would mean eliminating the provision in current law that ties recipients of temporary work visas to a single employer. If you’re working on a farm and being mistreated, you should be allowed to offer your services to the next farm over.

Expanded means both quantitatively expanding the number of visas available and also allowing temporary visas for work in sub-sectors like dairies that aren’t considered “seasonal.” Mostly, though, agricultural work is pretty seasonal. And it’s just a question of letting more people come and do it. Matthew Rooney, Laura Collins, and Cris Ramon also call for more H2B visas for temporary non-agricultural work.

Opportunists like J.D. Vance like to make the argument that immigration is a plot by the rich to drive down wages.

I think the bulk of the evidence says otherwise. I also think that if you’re worried about the aggregate skill composition of immigrant flows to the United States, far and away the best way to address that is to open the doors to more foreign-born doctors, dentists, engineers, etc. Own the libs by granting more visas to foreign professionals! I will be extremely owned!

That said, I don’t think anyone’s economic aspiration for their kids is to get a job doing seasonal agricultural work. Even at the depths of the Great Recession, native-born Americans were not clamoring for these jobs. And it’s challenging to use farm-labor shortages as a tool to raise wages because if you make labor-intensive crops expensive to harvest, people switch to imported crops or just eating other stuff. There’s no universe in which people are going to be buying hyper-expensive U.S.-grown strawberries or whatever. What happens in reality is that immigrant farmworkers create complementary jobs for Americans (manufacturing farm equipment or doing accounting work for farms) while doing very difficult work for pay that is considered desirable relative to the standards available at home.

The H2Bs are trickier and, I think for obvious reasons, a nonstarter with unemployment very high. But if Jay Powell and Co. really can bring the unemployment rate down below 4% by next year, then I think it becomes timely to have that conversation about H2B expansion.

The immigration debate needs to be about legal immigration

To me, it is just fundamentally bad that the “openness to immigration is good” pole of the debate has come to be occupied by the idea that “enforcement of immigration law is bad.”

What we should be aiming for is better-organized refugee resettlements (here Biden has already taken action), more pathways for skilled workers to get green cards, and legal opportunities for temporary work by less-educated residents of nearby countries. We should be exploiting foreign demand for our universities as a key source of comparative advantage. We should be letting Silicon Valley hire foreign-born programmers in unlimited numbers. We should be following Dean Baker’s prescription for free trade in medical services — aka let foreign doctors and dentists work here.

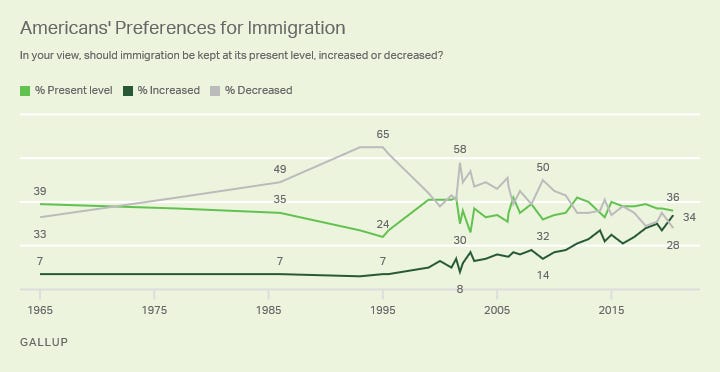

We should be inviting young, foreign-born college graduates to move to cities suffering population loss, where their presence will stabilize local economies. Public opinion has become more favorable to immigration, and I think that pro-immigration forces can win this argument.

But an argument about irregular flows of people transiting through Mexico and arriving without papers at the southern border is not a favorable terrain. Biden is already shifting back toward a crackdown. And though he can hopefully generate something of a kinder, gentler version of externalization of the problem, that’s fundamentally where this is headed. If we want the country to welcome more immigrants — and we should — we’re going to have to fight that out squarely, not try to sneak it through the back door.

Side note- There's a good amount of literature that the relationship between a country's income and emigration is inverse U-shape. Emigration takes thousands of dollars, so when a country is real power their people can't really afford to immigrate to another country. However, as the country's income approves their people have the money to immigrate to a higher income country where they believe their kids can have a better life. However, once the country's income reaches more of the middle income level, emigration slows down as emigrating becomes less attractive b/c of the lower income differential. For example, immigration from Mexico is much lower nowadays b/c Mexico has become middle income country.

So the United States shouldn't bet on immigration from Northern Triangle countries slowing down even if we somehow help their economies. It's going to take more than a one or two presidential administrations to get Northern Triangle's GDPs to converge to Mexico's. Meanwhile if their economies improve, there's a good chance that it might actually increase emigration b/c more people will be able to afford to pay the coyotes.

Who else here actually works with a lot of highly skilled/educated foreigners? I do, and watching them--STEM PhDs from fancy schools, etc.--struggle with visa issues has totally radicalized me. They're amazing, and dithering about keeping them when they would otherwise be in China or wherever but they want to be here is the most unbelievably self-destructive thing I have ever observed. I do not need the US government protecting my job from my brilliant colleagues. My brilliant colleagues are the reason my job is fun and prestigious in the first place. Chasing them out so people like me have less competition is the definition of cutting off one's nose to spite one's face.