Could a shutdown finally end the filibuster?

An extremely conflicted take

What’s striking to me about the whole looming potential government-shutdown situation is how straightforward it is from the standpoint of a House Democrat:

If President Trump is willing to negotiate a fair, bipartisan compromise with Democratic Party leadership, you vote “yes” unless you’re specifically trying to position yourself as a left-wing dissident. What is a fair bipartisan compromise? It’s hard to say, but it almost certainly includes some provisions designed to reassure Democrats that the White House isn’t going to just call “backsies” on the deal via impoundment.

If he’s not, you vote “no,” and …

If Republicans unanimously vote for the bill, it passes anyway.

If they fracture among themselves, it doesn’t pass.

In scenario 2b, there is a government shutdown, but Democrats can say that they did not shut down the government — the government shut down because Republicans can’t get their shit together and refused to negotiate in good faith.

One important aspect of this, both politically and psychologically, is that nobody in the House has to vote for a bill that they don’t think is good. Either Republicans agree to a bill that most Democrats think is good and it passes on a bipartisan basis, or else Republicans pass a partisan bill on a party-line vote.

Everything that is weird about the current situation stems from the Senate.

A bill could pass the House on a party-line vote and all the Republican senators could be prepared to vote for it, but it still wouldn’t pass the Senate unless a bunch of Democrats vote for it. But why would a bunch of Democrats vote for a partisan Republican bill? Of course Democrats aren’t going to vote for a partisan Republican bill! The problem is that if Democrats don’t vote for it, the government shuts down. And because Democrats have been “jammed up” by the sequencing, the public blames the Democrats for shutting down the government. This has happened repeatedly over the course of my life, and it’s never worked out well for the party in the Democrats’ current position. And I agree with Matt Glassman that what’s failed before is very unlikely to work now.

And yet, I can’t really bring myself to agree with him that it’s a terrible idea, because there is something absurd about negotiating an appropriations deal with a counterparty who reserves the right to break the deal. Why would anyone vote for a bill like that? I wouldn’t want to, and I think it’s more than just hysteria that’s making Democrats in Congress deeply reluctant to do it.

The actual solution here — rather than tactical advice to Democrats — is that filibustering is dumb and this is just another example of what a distorting influence it has on American politics. If Republicans have unified control of the government, they should just write and pass appropriations bills! They won the election.

The health care gambit

Last weekend, I wrote a Bloomberg column arguing for a narrow shutdown demand focused on extending Affordable Care Act (A.C.A.) subsidies.

I talked myself into this by starting with the premise that the base and the rank-and-file are clearly demanding a fight. And while I agree with Glassman that a shutdown fight is unlikely to work, a shutdown focused on A.C.A. subsidies had, I thought, two key virtues:

Even if it totally failed on substance, it would drive attention to the expiring subsidies, an issue that plays strongly in Democrats’ favor but is also boring and always getting crowded out of the news agenda.

There is non-zero Republican support in Congress for doing what Democrats want on this, so it’s at least conceivable that Dems could win the fight.

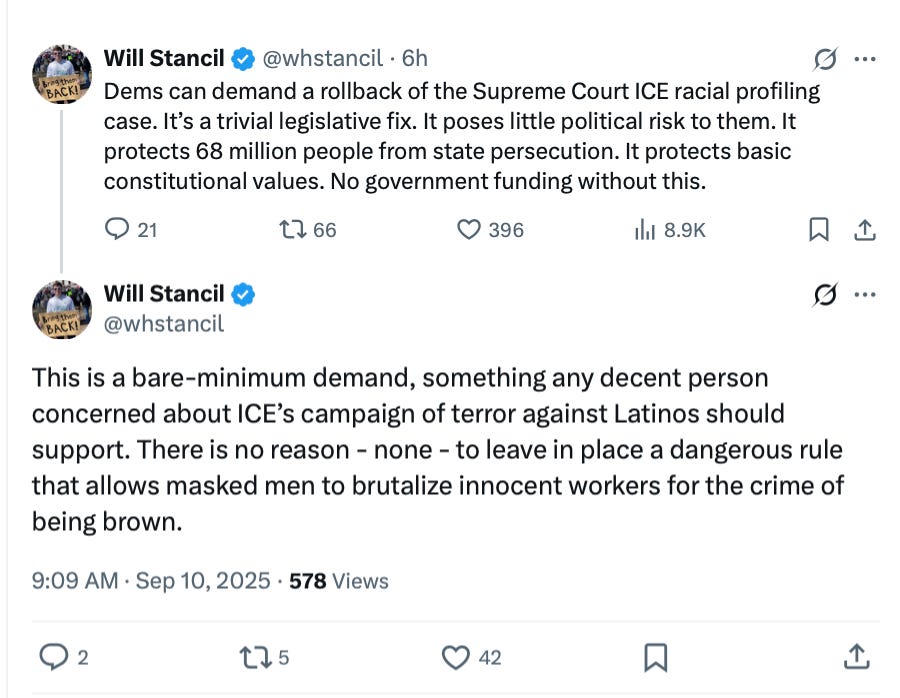

Basically, I was arguing for a harm-reduction shutdown. In a world where members and the base are champing at the bit for a fight, it’s best to pick a fight that you have some vague chance of winning and where, even if you lose, getting the issue in the headlines has upside. The risk is that if everyone who sympathizes with Glassman’s points takes his position, the baton passes to guys like Will Stancil, who want Democrats to pick obviously unwinnable fights that do nothing to help in any of the key Senate battlegrounds.

The problem with the health care gambit is that almost as soon as it got into the water it began to expand. Members were saying that if we’re going to fight over health care, we should fight for National Institutes of Health funding and against Medicaid cuts too. What’s more, extending the subsidies will help Republicans in the midterms, so do we even want to do that?

And I take the point that Brian Beutler made to me on Politix: Even though I’m trying to avoid the mistakes of past shutdowns, I am in fact directly copying the pattern of saying Democrats should hold appropriations hostage to a separate issue.

Beutler’s case is that Democrats should insist on an end to impoundment and rescission, because that is germane to the negotiation. If you want us to vote yes on a bill, then the bill has to mean something. For the bill to mean something, the money it appropriates needs to be spent. And I do think that beyond the larger psychological dynamics and a desire to be seen as “fighting,” this does get to the core of why almost no Democrats in Congress want to vote yes on a long-term continuing resolution or other measure that doesn’t reflect a real bipartisan process. When you vote yes on a bill that segments of your base wanted you to vote down, you want the ability to go back home and walk people through the provisions that you think are good and made the bill worth voting for. If Trump can just welch and not spend the money, that’s hollow.

What’s crazy isn’t that Democrats don’t want to vote for such a bill — it’s that their refusal to vote for such a bill would shut the government down.

The incredible vanishing filibuster

One of the untold stories of the current Congress is the extent to which Republicans are already chipping away at the filibuster rule.

In part that’s because of a major asymmetry between the parties. In typical Democrat fashion, the left-of-center community spent 2020 to 2022 having heated public arguments about the merits of the filibuster and the options for changing the rules and then did literally nothing.

Republicans, by contrast, have spent almost no time debating Senate procedure. Instead, they quickly and relatively quietly adopted a “current policy baseline” gimmick that allowed tax and spending changes that normally would be subject to filibuster to pass via the budget reconciliation process instead. Just last week they swiftly and quietly allowed for nominees to be confirmed in large batches so as to make it harder for the minority party to gum up the works. This follows their successful effort to rapidly, and without much debate, change the rules to make it impossible to filibuster a Supreme Court confirmation when Democrats tried it on Neil Gorsuch.

I have no real complaints about any of this. The current policy baseline is absurd as a way of looking at actual budget tradeoffs. But the filibuster rule is dumb, and I would rather scrap it than find weird loopholes.

Even as I’ve come to identify more as a moderate and less as a progressive, I continue to think that the merits of the filibuster is something that moderate Democrats really get wrong. It’s just not factually true that the era of ubiquitous filibustering was also some golden age of bipartisan legislating. The main reason that bipartisan legislating happens is that unified party control of the White House and both houses of Congress is relatively rare. And it’s often easier to get things done in a bipartisan way. Lots of Republicans think ethanol subsidies are dumb, and they’re right. But you’re never going to stick a knife in the back of farm states on a party-line vote. If that ever gets reformed, it’s got to be bipartisan. The same is true for the Jones Act and any number of other issues that involve concentrated costs and diffuse benefits.

Most of the good housing reforms that have been enacted in state legislatures have passed on a bipartisan basis, whether in Texas or Florida or California or Washington. That’s not because of magic filibuster rules; it’s because it’s much easier to do things when you can get some bipartisan cover. Filibustering just makes it harder to do things, including bipartisan things.

So if the endgame for the shutdown could be that Democrats refuse to vote for a partisan appropriations bill and Republicans reopen the government by ending filibusters for appropriations bills, I think that’s good. The Republicans get what they want (their preferred spending bill), the Democrats get what they want (the ability to vote no on legislation they don’t like), I get what I want (an end to the filibuster), and America gets to have a proper partisan tussle over appropriations, without all the procedural weirdness distorting things after the midterms. While Democrats won’t “win” the battle, we still end up with a better outcome.

Or maybe I’m wrong

I like my takes to have punchy conclusions, but I feel ambivalent about this.

One critique I’ve heard is that Democrats should be much more risk-averse about the filibuster. I know people who argue that if Trump pushes some kind of Enabling Act nine months from now, we’re all going to be really sorry that we scrapped the filibuster over an appropriations dispute.

I don’t really buy this, because deep down, I don’t think the filibuster really prevents anyone from doing anything. As we saw with Gorsuch, and even more clearly with the baseline hijinks, if the filibuster stands in the way of something Republicans care about, they just change the rules. Democrats, too, spent all that time paralyzed over filibustering not really because of Senate procedure, but because members were relying on the filibuster to paper over disagreements on the merits. This is part of what’s bad about the filibuster, and we should herald its decline.

My big doubt, though, is about whether Donald Trump gives a damn about congressional appropriations at all. The assumption underlying all shutdown talk is that if the government shut down, Trump would try to reopen it. What if he just laughs? Is R.F.K. Jr. going to be sweating the shutdown of all Health and Human Services programs? ICE will be designated “essential” and keep working. Maybe Trump breaks the law and makes sure they (and the troops and the other federal cops and whoever else he wants to keep operating) get paid on time and dares Democrats to sue to block the troops from getting their money.

If Democrats really pull it together and deliver a focused, coherent message, I think they can maybe navigate this situation. But I’m not sure they can do that. And I’m concerned that we would be plunging the country even deeper into a weird “state of exception” with no endgame. On the other hand, I’m deeply sympathetic to any senator who looks me in the eye and says, “I don’t want to vote for a temporary budget that just keeps current spending levels in place that the president then violates at will.”

All I really know for sure is that the existence of the filibuster is creating this dilemma, and I don’t think it’s good.

Congress is withering as an institution. For it to revivify, creaky old procedures have to go and legislating has to become possible. If you don’t like the imperial presidency, you should really hate the filibuster.

The correct synthesis is that both the filibuster and the concept of the government shutdown are bad and dumb and entirely self-inflicted and we can just get rid of both of them.