The American Rescue Plan was too big

Lawmakers spent too much, too quickly — and overlearned the lessons of 2009

This piece is written by Milan the Intern, not the usual Matt-post.

Back in 2009 when President Obama’s economic team was crafting his stimulus plan, soon-to-be chief White House economist Christina Romer calculated that it would take between $1.7 and $1.8 trillion to fill the “output gap” — the difference between actual GDP and estimated GDP if labor and capital were both being deployed at maximum sustainable levels. But Larry Summers, another top advisor and one with more political experience, said that Congress wouldn’t be willing to spend that much money, so the administration eventually settled for the $831 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, with the hopes that they could ask Congress to authorize further spending if ARRA proved insufficient.1

But Republicans swept Congress in the 2010 midterms, and that was the end of that. The consensus today is that Romer was correct and the stimulus enacted in 2009 was too small, leading to a slow and painful recovery from the Great Recession in which weak demand contributed to elevated unemployment and the Fed consistently undershot its inflation targets. So when Covid-19 plunged the country into another recession in early 2020, policymakers opened the fiscal floodgates, spending around $5 trillion to stimulate the economy. But overall CPI inflation is at 8.5 percent, and core CPI inflation is at 6.5 percent. Real wages are falling for much of the workforce, and the Federal Reserve is beginning to raise interest rates.

At the same time, the 2020 Democratic trifecta is on the verge of midterm defeat with remarkably little lasting-policy legacy.

And these two facts are related. The Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan was nearly as costly as Obama’s ARRA and the Affordable Care Act combined. But while Obama paired an inadequate stimulus with a major permanent program, Biden (with the support of all the Democratic Party’s congressional factions) just did a really big stimulus — pumping more short-term demand into the economy than was needed in a way that created inflation and undermined support for creating permanent new programs.

Overlearning the lessons of the Great Recession

Marc Goldwein of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget told me that policymakers since 2020 have made two key errors in generalizing their analysis of the 2009 situation to the present.

First, they overestimated the economy's potential and therefore the size of the output gap. And second, they misread the output gap as mostly reflecting a shortage of demand rather than supply.

Here’s a chart showing the year-on-year change in core PCE inflation, the Fed’s preferred measure.

As you can see, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, the inflation rate remained consistently below the Fed’s goal of two percent, even during the tight labor market of 2018 and 2019. This led people, including Matt, to believe that we had underestimated the size of the demand gap and that the economy could handle much more stimulus in order to achieve full employment. But it seems like full employment hawks were overly optimistic.

In 2009, we were clearly suffering from a pure lack of demand. Nothing about the real economy had changed — we had the same number of workers and factories and fuel and so on. But in 2020, we had a supply gap in addition to the demand gap because Covid-19 limited the capacity at which businesses were able or willing to operate due to a lack of labor and effectively a lack of space due to distancing requirements. And that’s something fiscal and monetary policy just can’t fix.

There was a ton of stimulus in 2020

When the virus first hit and the potential economic impacts became clear, Congress was not stingy. In March, they passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, spending $225 billion on a pandemic paid leave program, money for testing, and food assistance for the needy. That was quickly followed by the $2.2 trillion CARES Act negotiated between Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, which included $1,200 stimulus checks, $260 billion to boost unemployment benefits by $600 per week, $350 billion for the Paycheck Protection Program, and $340 billion in aid to state and local governments.

Then in December, Congress tacked another $900 billion in stimulus onto the annual omnibus appropriations bill. The package included an extra $325 billion for the PPP, a reduced $300 per week boost to unemployment benefits, $600 stimulus checks, and a good energy bill tucked in Secret Congress-style. According to the CRFB’s calculations, the December stimulus would’ve been enough to almost close the output gap for 2021, and perhaps even close it entirely under optimistic assumptions.

But then a funny thing happened. Having just lost re-election, Donald Trump threw a temper tantrum and threatened to veto the December stimulus, requesting among other things that the stimulus checks be increased to $2,000 before relenting and signing the bill. The House quickly voted to increase the size of the checks, but Senate Republicans blocked the measure. In Georgia, Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff promised that a Democratic Senate majority would deliver $2,000 checks — and they won.

ARP spent too much and too fast

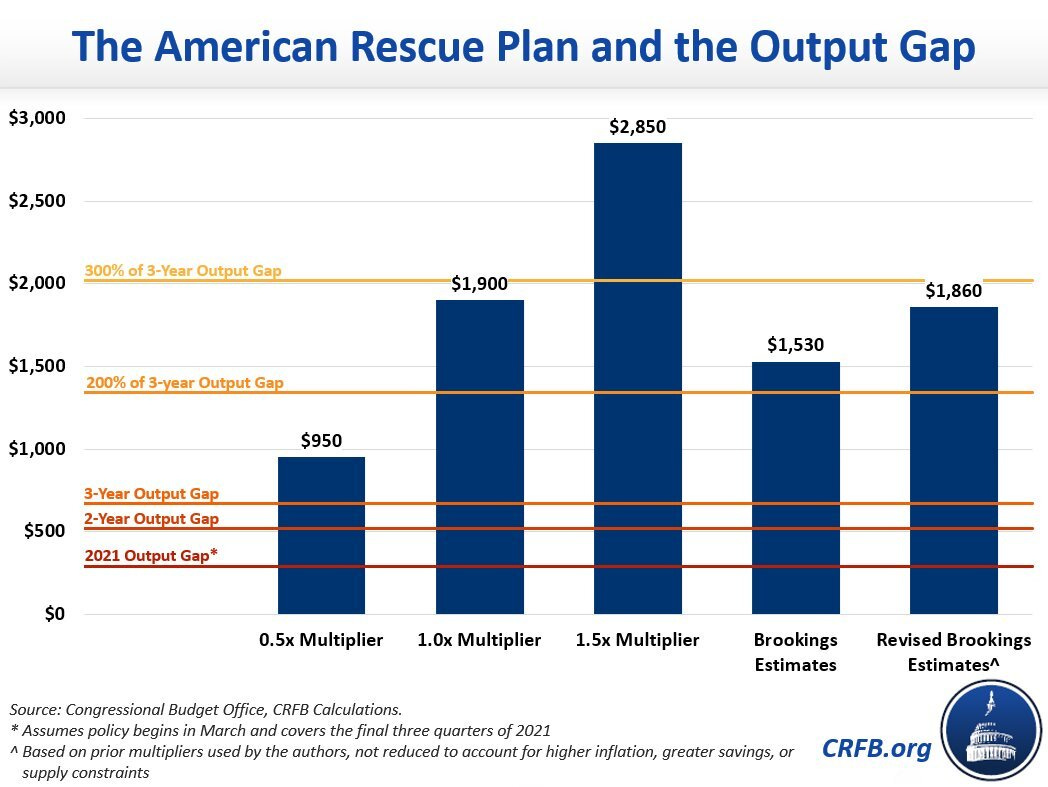

When Joe Biden came into office, his team quickly drew up a $1.9 trillion stimulus package: the American Rescue Plan. Summers argued that the bill was too big and would be inflationary, and the CRFB produced this chart showing that even assuming a low fiscal multiplier, the ARP would overshoot the output gap.

But people really thought that an overshoot would be okay! Vox’s Emily Stewart wrote that while the risks of going too big were real, “going too small could be riskier.” Matt argued that $1.9 trillion was “not too big.” Here’s Joe Biden, reflecting on 2009:

“One thing we learned is, you know, we can’t do too much here,” the president said while speaking to reporters in the Oval Office in February. “We can do too little. We can do too little and sputter.”

Democrats’ hope was to create an economic boom and lay the groundwork politically for an additional budget reconciliation bill passed on party lines. This second bill, they hoped, would take several of ARP’s one-year initiatives (the expanded Child Tax Credit, enhanced ACA subsidies) and make them permanent while also enacting major investments in clean energy production, care for the elderly and disabled, and family programs. The second bill was supposed to be Joe Biden’s legacy, but hopes for this second bill have dwindled over time. Once envisioned as a $3.5 trillion package over 10 years, it shrank to $1.7 trillion with lots of reliance on phase-out gimmicks. There was some thought of negotiating a true $1.7 trillion bill with Joe Manchin, but as inflationary problems have piled up, Manchin has become more skeptical of big new spending. Biden is now facing the possibility of securing none of these major legacy items, while progressives are left to hope that they can maybe salvage the energy investments.

The rise and fall of Build Back Better and its relationship to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework have generated lots of factional infighting. But the real problem was the bill all factions agreed on — ARP spent $1.9 trillion in essentially just one year. Doing fewer things while spreading the money out over a longer span of time would have left the economy in better shape while also securing a more durable legacy.

Of course, any such effort would also need to take political reality into consideration.

Goldwein argues that the $1,400 checks were a mistake from a macroeconomic perspective. That may well be true, but politically it would’ve been impossible not to do the checks after promising them in the Georgia runoffs. But Democrats could have structured the $1,400 as $100 monthly checks with a somewhat sharper means test instead of the lump sum to smooth out the spending and reduce the inflationary impact. And that’s just one area where ARP could have been productively restructured.

State governments didn’t need extra aid

During the Great Recession, state and local governments saw their tax bases contract drastically, with effects such as long-lasting budget cuts for public colleges. Initially, there was good reason to worry that we would see a repeat of that cycle. If you look at tax data collected by the Census Bureau, you can see that most states lost revenue in fiscal year 2020 compared to FY 2019.

But FY 2020 ended in October and stimulus money takes time to disperse, so that data doesn’t tell the whole story. In addition to the direct aid appropriated in CARES, states got to tax expanded unemployment benefits and stimulus checks, and some got a windfall from corporate and capital gains tax collections swelled by a booming stock market. So by the time ARP was being written, it was clear that state finances were in pretty good shape.

Charles Lane wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post arguing that the ARP was being too generous with state aid, and the CRFB summarized the arguments for less aid:

For example, Moody’s Analytics recently estimated that an additional $86 billion of aid is needed to cover revenue losses, while a number of experts at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) have argued an additional $100 billion of aid is warranted. Even the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), which has been a strong advocate of large state and local aid, estimates $225 billion of net revenue shortfalls (each of these estimates assume states will use their rainy day funds).

In hindsight, the lower figures seem to have been correct: aid should have been much more limited and only allocated to replace lost revenue.

It would be one thing if the state aid was excessive but ultimately benign, but it’s making the economic situation worse. Despite ARP provisions designed to prevent this kind of thing, many states including Arizona, Iowa, and Wisconsin are using the money to pay for large, permanent tax cuts, even though the windfalls they are enjoying are the result of temporary policies such as expanded unemployment benefits and more generous federal contributions to Medicaid. This places them at risk when the next downturn hits and contributes to a negative cycle where states need federal aid in lean times and then cut taxes in good times, which means they require even more aid next time.

Lessons from 2021 and beyond

The bottom line is that the American Rescue Plan, while well-intentioned, spent too much money too quickly, meaningfully overshooting the output gap and contributing to inflation. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, pandemic fiscal stimulus (CARES and ARP) increased the inflation rate by three percentage points by the end of last year. In hindsight, Democrats should have passed a smaller bill, with less upfront stimulus and more spread-out spending on permanent programs. The CRFB put together a framework for a slimmer package totaling $1.1 trillion featuring fewer temporary programs, reduced aid to states, and automatic stabilizers.

If I were given a magic wand and a time machine, I would write a bill looking something like this, with emphasis on doing a few permanent programs while delivering a modest stimulus to the economy.

While slightly smaller than the actual bill, $1.55 trillion is still a tremendous amount of money, and I think this package would have spent that sum in a wiser and less inflationary manner than the real-world ARP did.

Going forward, we really ought to enact automatic stabilizers that adjust spending based on economic conditions for programs such as expanded unemployment benefits and state aid. When Democrats had the chance to let the economy go up in flames and tank Donald Trump’s re-election, they did the right thing and put country over party. But we might not get so lucky next time. The fate of the economy shouldn’t rest on whether the speaker or the Senate majority leader feels like doing an opposite-party president a favor.

But in the present, what we have to do is stop the bleeding. That means reducing the deficit and the Fed increasing interest rates without throwing us into a recession. It means reducing energy prices and capping the cost of insulin and prescription drugs. It means winding down Covid-19 relief spending that is contributing between 0.14 and 0.68 percentage points to the inflation rate and diverting unspent stimulus funds to pandemic prevention and ending the pause on student loan payments. And we should do what we can to address the supply side by promoting vaccination, making pharmaceutical treatments available, and otherwise accepting the new normal and getting back to our lives.

Technically Congress did around $1.8 trillion of stimulus between 2008 and 2012, but given the high unemployment and low inflation rates observed for years after the Great Recession, Romer’s estimate of the size of the output gap was almost certainly too small.

You sure you haven’t been to college yet? Good article Milan.

I’m curious as to your final prescription to end college loan forbearance. I actually think it’s right, but wow the backlash.

I also think that the switch from services to goods should be mentioned every time we talk about Covid and inflation.

On a related point, the migration of people from cities to suburban areas probably Exacerbates this. If u live in an apartment you have less room for stuff. You use more services. In suburbs we have entire garages and rooms to fill with stuff. Lawn mowers. Spare beds. 65 Mustangs. Etc.

I also wonder what this whole thing says about Yangs Basic Income proposal. Doomed I expect.

Anyone else see great twitter battle between Matty and Rep Ro Khanna