Against the "price gouging" theory of inflation

Demand-pull inflation by another name

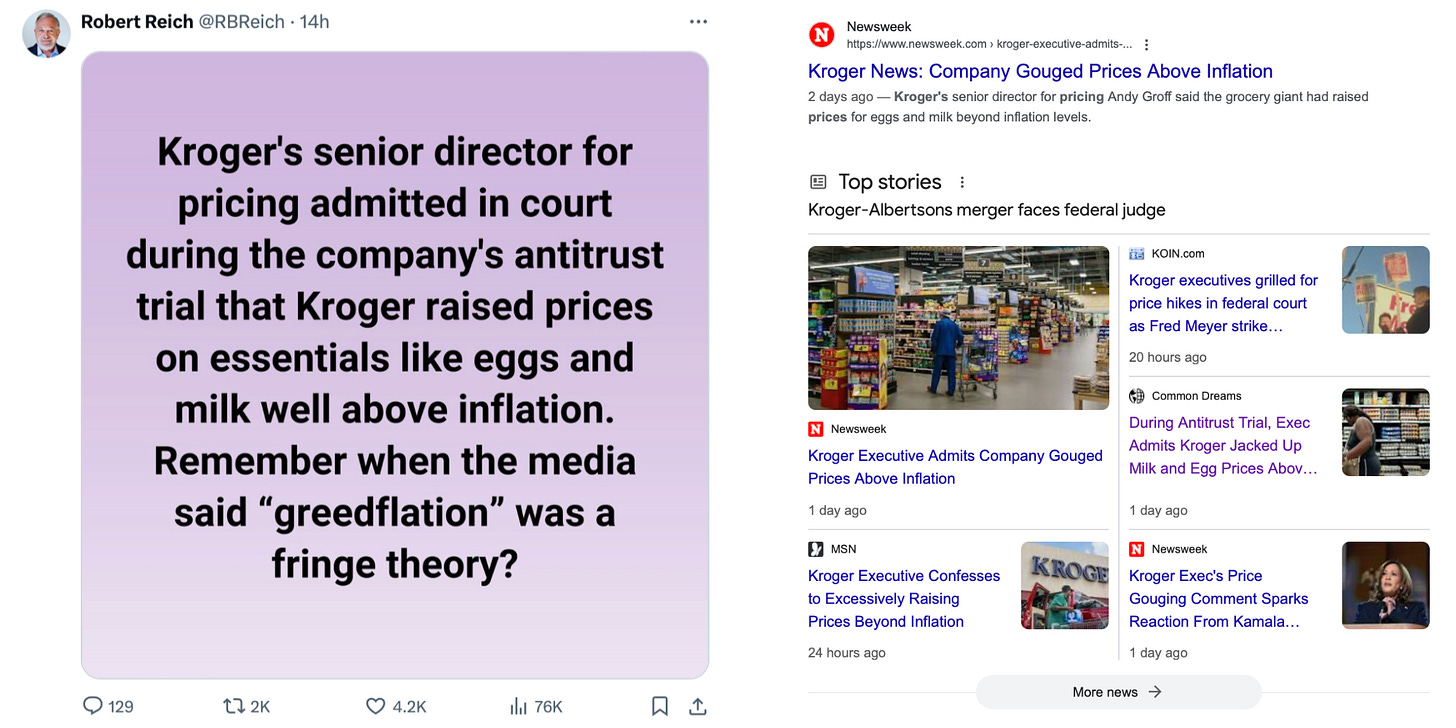

Hello! Today is Labor Day, and on federal holidays, we like to un-paywall and re-share a classic from the archives. Today’s piece originally ran in May of 2023 under the headline “Greedflation is Still Fake.” I’m bringing it back because I was considering writing this week about the theory that Kroger executives made a damning admission of “price gouging” when they conceded that they had raised grocery prices by a larger amount than their input costs went up.

The implication here is that you would expect retail prices to be a pure function of input costs rather than a function of supply and demand. But this doesn’t make sense! Rather than discover a new cause of inflation or a new theory of how it works, leftists have just decided to relabel standard demand-pull inflation as “price gouging.” Of course, people can use words however they want, but as an economic policy argument, this doesn’t get you anywhere.

Below is the original piece; I hope you enjoy it!

Greedflation is still fake

David Sirota roped me into a piece he wrote last week, the thesis of which is that “after corporate media lied America into a war and a financial crisis, data show they lied about a main source of price hikes — and brutal policies followed.”

My alleged sin was the May 2022 article “Greedflation is fake” about takes like this one from Public Citizen, which appeared to be arguing that inflation was caused by some kind of exogenous increase in corporate greed.

At that time, some were floating the idea that the economy needed price controls in order to combat this surge in greed. If you need to jog your memory, I’d recommend reading Robert Reich’s article “Corporate greed, not wages, is behind inflation. It’s time for price controls.” Or taking note of Elizabeth Warren’s “Price Gouging Prevention Act of 2022,” which would have turned the FTC into a kind of national price regulator.

There is absolutely a time and a place for price controls and rationing in economic policymaking. One of my grandfathers was a communist and a naval aviator during World War II. My other grandfather was an economist who spent the war working at the Office of Price Administration where he helped secure the future of the free world by organizing a rationing and price control system for footwear. I recommended rationing and price controls for Europe during the winter of 2022-2023 to help deal with Vladimir Putin’s efforts to cut off the continent’s supply of natural gas.

But my point in the greedflation piece was twofold:

Greed is a constant in the economy, not a variable, and it doesn’t explain why inflation was so much higher in 2022 than in 2019.

Price controls and rationing are a reasonable response to certain kinds of supply disruptions associated with war or natural disaster, but if you use them to address run-of-the-mill excess of demand you end up with shortages.

Sirota’s new piece completely ignores the text of what I actually wrote, and instead goes to town on the idea that a large share of the increase in prices is accounted for by an increase in profits. This supposedly proves that I am part of a cabal of media liars whose “inflation myth crushed the working class.”

This is nonsense.

The whole point is that overstimulating the economy generates price increases and windfall profits, which is why ideally you wouldn’t overstimulate the economy.

We somewhat overstimulated the economy

A good clue as to how we ended up with an overstimulated economy is Joe Biden’s statement on February 5, 2021 that “the way I see it is the biggest risk is not going too big — it’s if we go too small.” I heard similar variations on this theme both on and off the record from the White House’s economic and communication teams multiple times during the transition and during the debate over the American Rescue Plan. Joseph Stiglitz, endorsing the administration’s approach, explained several months later that “while weighing the risks, we also must plan for all contingencies. In my view, the Biden administration has correctly determined that the risks of doing too little far outweigh the risks of doing too much.”

This is something that I also said at the time because I thought it made a lot of sense.

Policymaking is difficult because it involves a lot of uncertainty. If, when faced with uncertainty, you decide it’s important to err on the side of overstimulating rather than understimulating, then the odds are good that you will end up overstimulating. And that’s what happened.

With my critical hat on, I would say that relative to sound policy design, the ARP made two errors. One is that it included a bunch of state and local fiscal aid money that was knowably unnecessary given the actual condition of state budgets. This has contributed somewhat to inflation, and also politically allowed Greg Abbott, Ron DeSantis, and other GOP governors to position themselves as hostile to Biden’s big spending while also using Biden’s big spending to cut taxes and hand out raises to cops and teachers. The second problem with ARP is that it included a pilot version of the refundable Child Tax Credit that was always meant to become a permanent program and not a temporary stimulus. That’s fine in the spirit of “don’t let a good crisis go to waste,” except it turned out that Joe Manchin had fundamental objections to the idea, which meant it wasn’t a good idea to spend money on it.

But still, the correct policy ex ante was to do something that more likely than not would look like overstimulus ex post. And that was the stated policy.

And as I said, despite certain quibbles, I think it was a fine calculus. The past couple of years of high inflation have been tough. But inflation is falling and I don’t think the bad inflation of the past will have any serious long-term consequences for the American economy. That’s in contrast to high unemployment, which causes a lot of long-term scarring. The super-rapid jobs recovery is a very important policy achievement, and inflation has been an unfortunate downside of that achievement. But it’s very easy to understand in conceptual terms, and it fits perfectly with the observation that profit margins have risen.

Supply, demand, and profits

Two things can happen if demand for the goods or services you sell goes up. One is that you can sell more stuff — an increase in quantities. The other is that you can raise prices.

What one hopes for in a stimulative policy is a large increase in quantities and a small increase in prices. And at a time of high unemployment, that’s a very reasonable thing to hope for. After all, most companies should be able to relatively easily increase quantities sold by hiring unemployed people to do the extra work. That’s the stimulus working.

But if you go too far, the economy starts to run out of easily available unemployed workers, so the quantities don’t increase much. When there’s a lot of demand for something and the quantity of that thing can’t expand very much, what happens is that prices rise a lot (inflation), which creates a windfall for sellers (profits).

Note that while you can certainly turn to any one individual company and say “why don’t you just raise wages if it’s hard to recruit unemployed workers?” this does not work for the economy as a whole. When there are lots of unemployed workers, you can have a large shift of people from not producing anything to producing something, and production rises. But when there are few such workers, people are mostly switching from producing one thing to producing another thing, and the increase in aggregate production is small. Part of the inflationary process is indeed that nominal wages go up a lot (this has been happening), but prices go up, too. In other words, a large share of the price increases induced by overstimulating the economy are captured in the form of windfall profits.

That is, indeed, undesirable. But it’s not an alternative to the “too much stimulus” explanation for inflation; it’s a description of why, ideally, you would not do too much stimulus.

As we already covered, I think the Biden White House mostly had good reasons to do what they did. But I would like to see progressives acknowledge that ARP was mission accomplished (and then some) on stimulating the economy. The risk of going too small was larger than the risk of going too big, so they went very big and it worked. But that means depression economics is done and it’s time to return to regular economics with tradeoffs rather than have this weird argument about profits.

What is this argument even about?

The blessing and the curse of the internet is that it lets people converse across vast differences.

And to an extent, I think the American inflation debate is getting crossed up with a debate happening in Europe where the situation is different. European governments did less fiscal stimulus, European countries faced a bigger supply shock from the Russia/Ukraine war, and European societies have different labor market institutions. In Europe it is common to have much stronger labor unions, sectoral bargaining, and even some degree of what’s called “tripartite bargaining” where the government, unions, and the corporate sector work together to set wages.

In a tripartite system, if the government pushes very aggressively for wage hikes in excess of productivity, that could create a “cost-push” scenario where companies must raise prices or else be driven out of business. In a tripartite system, the government also could try to generate disinflation by forcing workers to accept lower wages. In that case, making the point that profit margins have actually expanded would be a good counterargument to the proposal. So when European Central Bank chief Christine Lagarde argues that profit margins statistically account for a large share of inflation, she is intervening in a European policy debate (it’s in the name of the bank) with limited relevance for the American situation.

What’s actually happening in the United States is that the Federal Reserve has been raising interest rates.

This has reduced asset prices nationally and altered time preference in a way that’s bad specifically for software startups. It’s also created a fair amount of problems in the banking system. If you’re a major shareholder in a medium-sized regional bank, this has not been a good spell for you. But Sirota’s claim that the working class has been “crushed” by “brutal policies” inspired by greedflation doubters doesn’t make any sense. The pace of job growth has slowed down, which is what you would expect with a very low unemployment rate. I’d expect it to continue slowing down. The prime age employment-population ratio is near record highs and overall population growth has become much slower than it was 20 or even 10 years ago, so we’re not going to keep adding jobs rapidly.

Greedflation nonsense just serves as a pointless distraction from what’s actually needed: policy focus on supply-side reforms that allow for productivity growth and real wage gains. Trying to use price controls to prevent excess demand from transforming into rising profits and prices is only going to generate shortages and make it harder to unwind the underlying pathology. We just need to admit what happened here — the architects of ARP deliberately erred on the side of going too big with stimulus and we’re now living with both the upsides and the downsides of that choice. I think the upsides far outweigh the downsides:

Prime-age employment is at the highest level of the 21st century.

Wages are growing fastest at the bottom of the distribution.

Black unemployment is at the lowest level on record.

Women’s employment rate is at the highest level on record.

This is not to deny that inflation is bad, but the long-term benefits of a strong labor market are considerable and inflation is a surmountable problem. I believe the choice to go bold on full recovery as soon as possible will work out well in the end. But to make it work out well, we need to make smart, ongoing choices that reflect a cogent understanding of the current situation, which means acknowledging that price increases have been driven by strong demand, and the alternative of rationing would make things worse.

I have a huge issue. People received a lot of money in stimulus and saved a lot of money by being at home. Indeed the credit card companies were worried as balances had been paid down so much. Now the public could have just accepted their new and better financial position and continued on. But no. They had to rush out and spend all the money burning a hole in their pocket. And that caused inflation.

I was just reading the comments on a NYTimes about the housing crisis. Almost every comment was about how it’s all the fault of private equity. Even though it’s obvious the people claiming it’s all private equity are the same people apoplectic at the thought of a townhouse going on down the street.

It’s always someone else’s fault and it’s always people clinging onto a comfortable lie rather than confront their own complicity.

You've missed the role of market power here. As Flavio Menezes and I have shown, firms with market power will increase their profit margins when demand is strong. That doesn't require any assumptions about increasing greed or increasing market power, and fits with the way a lot of people understand "price gouging".

Menezes, F., and J. Quiggin. 2022. Market Power Amplifies the Price Effects of Demand Shocks. Economics Letters 221 11090.