Zohran Mamdani’s strong start

I feared disaster when he won the primary, but so far so good.

Zohran Mamdani’s approval ratings in New York City and New York State seem to have improved substantially between when he won the election and his inauguration last week.

I don’t live in New York, but I am part of the “warming to Mamdani” trend. A bit before the first round of the mayoral primary, I said I was dismayed that a field that featured several genuinely good candidates was winnowing to a choice between a bad option (Andrew Cuomo) and a potentially catastrophic one (Mamdani). But by the second Cuomo-Mamdani matchup in the general election, Mamdani had convinced me he was the better choice. And during the transition, he mostly made good reassuring moves.

My preferred path forward for American politics would be for politicians who I like to take over the Democratic Party on an explicit program of moderation. But a plausible second-best scenario is one in which self-identified progressive factionalists take over and then become ruthlessly pragmatic because they want power. There are sporadic hints of this in things that Bernie Sanders and A.O.C. say and do, and I think Mamdani has been on this trajectory ever since it became clear that victory was within his grasp.

Genuinely the worst of all worlds, I think, is a continuation of the Hillary/Biden trajectory in which establishment figures with moderate roots are so terrified of losing power to the left that they abandon the substance of moderate politics. I think it’s quite clear that policy moderation helps you win elections, but I don’t think voters care about meta-discourse on ideology or are impressed by dog-whistle forms of moderation.

Mamdani did not make himself over as a “moderate” or abandon his brand as a leftist outsider. But he has moved to address the substantive concern that he is soft on crime, has aggressively courted the YIMBY/abundance-minded set of economic moderates, has tried to avoid making any alarming moves on education, is attempting transactional outreach to small-business owners, and is trying to build bridges to moderate Democrats in state and federal politics (for example, by crushing Chi Ossi’s abortive primary challenge to Hakeem Jeffries).

Along the way, he has remained uncompromisingly progressive on Palestine — an issue that seems to be very close to his heart and on which public opinion has genuinely moved significantly left — in a way that keeps him distinctive. He of course cannot liberate Palestine as the mayor of New York City. But he can try to do a good job as mayor and be popular and successful and thereby demonstrate that conventional pro-Israel politics is out of juice, meaning that he does not need to try to reassure people on this front. Alternatively, if he scares off businesses or lets crime rise or screws up the schools, he knows there’s no shortage of detractors who’d be thrilled to dance on his grave and discredit the whole democratic-socialist project.

He’s familiar with the “sewer socialist” tradition out of Milwaukee, the basic message of which is that the best way to be a socialist mayor is to try to be a good mayor who delivers good city services. I’m not sure he can pull it off, but I find his early moves encouraging.

Mamdani also has the Trump-like quality of keeping both friends and foes focused on what he’s saying rather than what he’s doing.

His inaugural address included a bizarre line about his desire to “replace the frigidity of rugged individualism with the warmth of collectivism” — a phrase that doesn’t even sound like how left-wing Americans (who are very individualistic even if they have bad ideas about economics) normally talk or think — which was immediately denounced all up and down conservative media. And progressives, in turn, spent days defending their man and poking fun at the Zohran Derangement Syndrome on the right rather than infighting over his moves to the center.

Mayor of New York City is a high-profile job, but one that’s objectively difficult to use as a launching pad for higher office. The odds are against him. But I think he’s off to an encouraging start.

Mamdani’s moves to the center

The most important move he’s made, by far, is that months ago Mamdani started walking away from his record as a “defund the police” guy. His actual record of statements on this was very clear: He wasn’t just fussing about funding levels. Back in 2020, he fully hopped on the bandwagon of referring to the New York Police Department as both “racist” and a “rogue agency.”

But after a certain amount of hemming and hawing, he did the right thing and just apologized.

Of course, nothing that he’s done on this score has stopped people on the right from characterizing him as a dangerous left-wing extremist. Any time you flip-flop, you’ll find it hard to persuade most people that your new stance is sincere, and, no matter what you say, your opponents will keep slamming you harshly. Those considerations are how people talk themselves into the idea that moderation has no value. But I think Mamdani is showing that’s wrong.

Has he convinced everyone that his views have changed? No. Has he convinced Jessica Tisch to stay on as police commissioner? Yes. Do I think he is now tough on crime as a matter of profound conviction? Not really. Do I think he is now seriously worried that a rise in crime would derail his political career and therefore he needs to work extremely hard to avoid one? Yes.

And that’s probably good enough.

New York is actually a low-crime city, so it doesn’t particularly need a mayor whose passion project is law and order. What it does need is a mayor who is risk averse about public safety and prepared to empower qualified professionals to keep things on track so that he can focus on other problems.

Alongside the collectivism bit, in his inaugural address he also promised to “free small-business owners from the shackles of bloated bureaucracy.” This is a theme he debuted as a pitch to make it cheaper and easier to get halal cart permits, which was a form of deregulation culturally aligned for his particular Muslim/hipster coalition base.

Over time, though, he has built it out conceptually to the idea that regulatory burdens fall especially hard on smaller businesses and he wants to help reduce them. He has also tapped some leading figures from the neo-Brandeisian community for his administration, but I want to call out that this unshackling genuinely differs from neo-Brandeisian small-business politics. He’s not saying he wants to be conceptually hostile to chains, or to make it harder for small businesses to become big or for their owners to sell them. He is promising concrete deregulatory measures to help small businesses thrive. It’s just straightforward, moderate pro-business politics facilitated by some ideological fudging.

Similarly, on K-12 education, Mamdani decided after the election to abandon his promise to end mayoral control over the school system. Ending mayoral control is a longtime goal of teachers’ unions, which don’t like power to be concentrated in the hands of a high-profile official who is accountable for results. Their dream is for everything to be handled in low-profile down-ballot elections that they can dominate. I don’t anticipate any amazing things happening on education under Mamdani, but he’s moved to the center on this and picked a seemingly status quo chancellor and praised the Adams administration’s phonics initiatives. What I find especially encouraging here is that the key change happened after the election. It’s not just a stunt to appease nervous voters (they didn’t actually seem to care much about education during the race). Mamdani is trying to narrow his focus, and waging a battle in the state legislature on behalf of teachers’ unions over mayoral control is not part of the agenda.

The prospect of left-abundance

Where he is very much sticking to his progressive guns is on transportation issues, which in the New York City context means things like championing bike lanes and road diets over maximizing car speed.

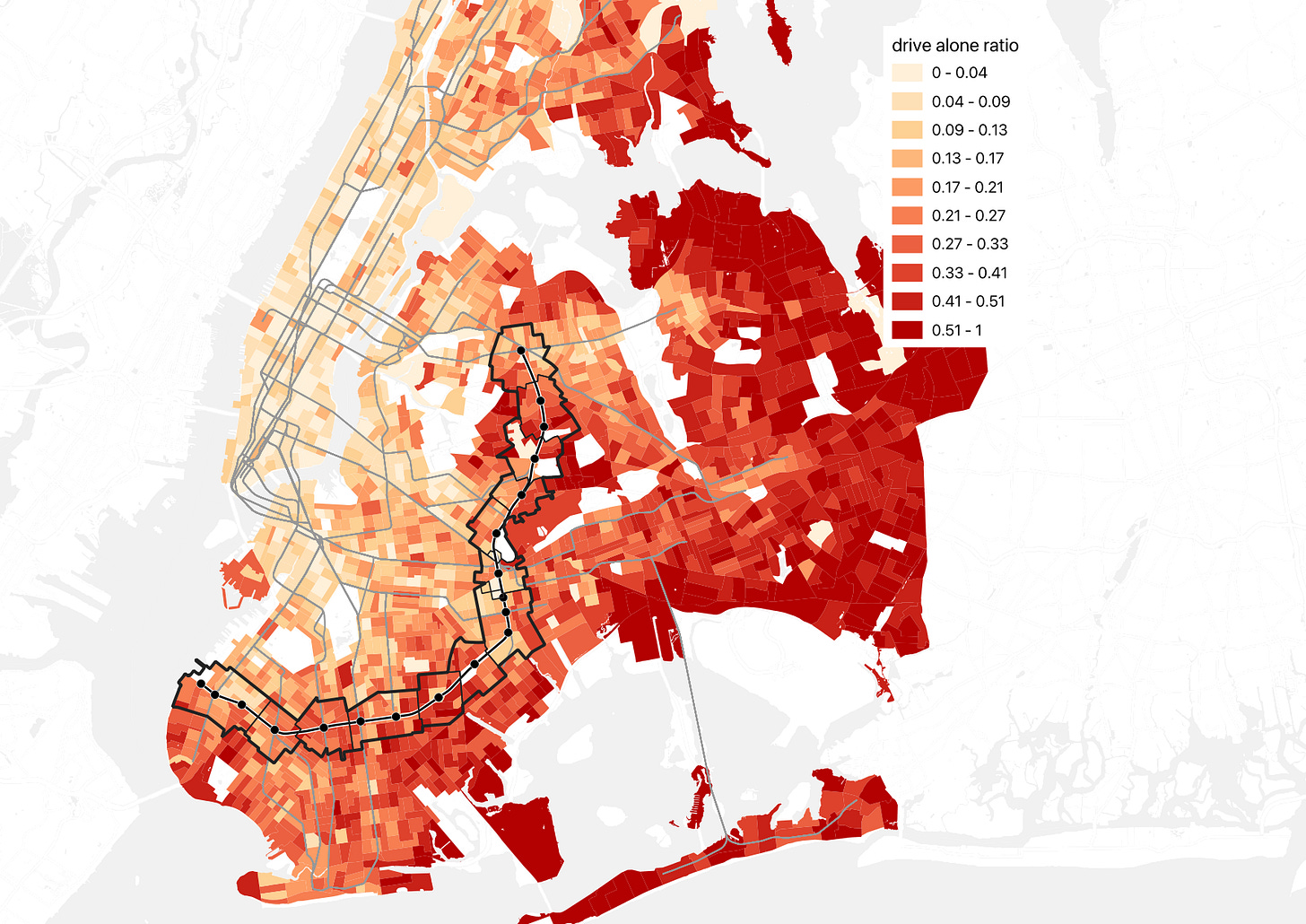

This kind of thing really ought to be a technocratic question without a lot of ideological baggage. But if you look at a map of the modal splits in New York City, you see that there’s a strong association between the car-oriented parts of the city and the politically conservative parts of the city — a correlation that only grows stronger if you consider Staten Island, where there is no subway service.

This association is not an iron law, of course. The Upper East Side was a stronghold of anti-Mamdani voting and is very transit-oriented. Not coincidentally, Michael Bloomberg was both a factional moderate and a champion of alternative transportation. But broadly speaking, this cause is associated with the left in the city, and they also happen to be (in this context at least) right on the merits. Congestion pricing was extremely controversial and a huge lift, but it was the technocratically correct policy, it has worked well, and political support for it is rising. Being the kind of progressive who champions good progressive ideas while dropping unsound ones is smart.

A similar dynamic helps explain why Mamdani has emerged as a bigger champion of housing development than the newly elected Democratic governors of New Jersey and Virginia, even though it’s in some ways a more natural fit ideologically for the more moderate figures.

Among real ideologues, YIMBY = deregulation = right-wing. But one thing newer academic research keeps showing is the importance of symbolic politics and aesthetic judgements to housing.

Basically, people who subjectively like dense neighborhoods are more supportive of upzoning, and that includes neighborhoods they do not live in. Obviously people who don’t like density don’t want to upzone their own neighborhood, but the point of this research is that the link to symbolic considerations extends well beyond self-interest. Mamdani’s base not only lives in high-density neighborhoods, but is disproportionately composed of people who deliberately moved to New York City from elsewhere. Even if they’re not gung-ho about deregulation, they are gung-ho about denser building forms and influxes of newcomers.

From the beginning, Mamdani’s outreach to swing voters has primarily emphasized his YIMBY streak, which aligned him with the outgoing Adams administration but contrasted strongly with Cuomo. He then put a strong YIMBY in as deputy mayor for housing, signed multiple YIMBY executive orders on his first day, and name-checked abundance in his inaugural address.

Finally, on the urbanism front, while I continue to think the “free bus” pitch is a somewhat misguided waste of money, in recent months he has consistently characterized the plan as “free and fast bus,” which incorporates the aspect that is actually important.

In many contexts, “free bus” reads to me as politicians wanting to be pro-transit while actually giving up on the hard work of addressing transit quality. Shorn of the bad ideas around policing and education, we’re now looking at what seems to me to be a plausible left-wing version of an abundance agenda focused on increasing the supply of housing and public services. And we have a mayor who is charismatic enough that his own supporters are mostly focused on being excited about what’s in the agenda rather than getting mad at what’s been cut.

Getting to win-win

Of course, as you would expect, it’s not like all of Mamdani’s moves have been ideas that I love. He’s given big jobs to Julie Su and Samuel Levine and other figures from the leftward end of the Biden administration’s economic regulators. That’s not to say these guys’ ideas are all bad. Informed people tell me Levine’s proposals with regard to app-based delivery companies address good-faith safety concerns and aren’t just pretextual hostility to big business. Regulation is important, especially in a big crowded city where everyone’s actions impinge on everyone else.

But there is a contrast of worldviews here that speaks to the dilemmas of left-abundance.

One big thing that progressives want to do is spend more money on helping people. That’s Mamdani’s plan for child care and is also reflected in the revised version of his thinking on public safety. In his inaugural speech, he argued that he needs a new agency to “tackle the mental health crisis and let the police focus on the job they signed up to do.”

And in a city like New York, by far the best way to obtain fiscal resources is to simply dismantle barriers to growth. If you let profit-seeking developers build market-rate housing and sell or rent it to affluent people while delivering on the promise to make it easier for other profit-seeking people to launch and operate businesses aiming to sell services to those new residents, you will get a revenue windfall. That windfall will make it easier to invest in transit, mental health, child care, or whichever public service you like. Doing this requires you to win a political fight with people who’d rather use the windfall for tax cuts. But it absolutely does not require some kind of twilight battle to the death against a wealthy oligarchy.

Something that I see all the time on the D.C. Council is that often the progressive members are better, conceptually, on housing and land use issues than the moderates. As with Mamdani, they tend to have a younger, more transient, more instinctively urbanist electoral base that does not fear density or newcomers and is ready to say yes to new housing of all types.

But those same members also have the instinct to say yes to every regulatory proposal that comes down from tenant groups, labor groups, green groups, and whoever else, which ultimately creates an unattractive environment for investment. I don’t anticipate Mamdani embracing my gospel of billionaire positivity, but you fundamentally can’t have housing abundance without embracing the legitimacy of the profit motive — which is not how these regulatory appointees think.

Still, all in all, it’s a very positive start to his term. Especially because, from where I sit, the entire trajectory since winning the primary has been very positive.

One of the nice things about democracy as a political system is that, at least when it comes to executive office, the incentives are pretty aligned. To be a successful leftist mayor, you need to be a successful mayor, and to be a successful mayor you need economic growth and safe streets and to avoid blowing up your school system. After a primary campaign that I found alarming — though obviously it worked — Mamdani has done a lot to indicate that he understands what the job is and wants to build a strong team and do it well.

It also helps that he has that quality that makes you want to root for him. There’s something attractive about his youth that allows you to see him evolving in front of you. Apparently, yesterday he name checked a transportation Vital City writer when he was asked about streetscape during Congestion Price celebration. There is an openness that draws people in.

The other thing is that while Zohran is super woke he doesn’t seem preachy like he is looking down on you for not agreeing with him. AOC can never fully pivot but she can learn from Zohran on how to deal with skeptics on both culture & econ. He avoids evincing resentment towards either the rich (Bernie) or the culturally conservative (AOC).

I feel like you unwittingly made the case for why new fresh faces taking power is actually pretty important to a functioning democracy.

You’re note about how in DC it’s the younger council members who are more YIMBY is instructive. You’ve touched on this before but I think it’s really underemphasized how much the YIMBY/NIMBY divide is an old vs young thing and not a right vs left thing.

I think about our last two presidents and how much their mental mindset of the world was basically set in the 70s and 80s. For Biden, it meant supporting old school unions like Dock Workers when it wasn’t all that clear this is a group worth supporting anymore given realities of modern technology. It also meant treating the Presidency as a senate majority leader straight out of the late 80s and early 90s which is likely how you got “the groups” getting too much influence* (that and it seems like his focus was extremely foreign policy oriented which meant domestic concerns kind of feel by the wayside).

For Trump it’s almost a cartoonish version of this. I still think “protect the housewives of Long Island” is an underrated window into his worldview. I feel like David Roth nailed this when he noted that somewhere around 1990 Trump’s brain turned to goo and he became incapable of learning anything new. Hence is late 80s obsession with tariffs never changing.

I think in cities it’s a little bit different but has similar dynamics of council members winning in uncompetitive elections and basically protecting in the desires of various interest groups that got their ear years maybe decades prior (guessing this how absurd rules around building scaffolding in NYC manage to stay around. Zohran that’s a good one to tackle).

So all in all. Somewhat tongue in cheek, I guess I’m calling for “Gallego 2028”.

* in fairness, Biden’s long time in the senate probably did help pass more bills than expected. We sort of forget how much more legislatively successful his term was than we expected. But it still sort of came about because of Biden’s ability to play on sort of the last vestiges of how senate worked 30 years ago instead of tackling the inert institution it’s become today.