William Julius Wilson Thought deserves a comeback

J.D. Vance's favorite sociologist explains "The Wire" and so much more

I never took a class with William Julius Wilson in college, but I did hear him speak a few times. I was also assigned his work in a course, and generally speaking, when I was learning about the intersection of race, economics, and politics, he was considered one of the leading intellectual figures.

So I found myself somewhat surprised by how rarely his work came up during Trump-era conversations about race and racism, and in particular, that his voice was largely absent from the great “reckoning” that followed George Floyd’s murder.1 His school of thought on these matters unfortunately seems to have slipped into a sort of obscurity. We instead had a brief time in which the naive and unworkable views of Ibram Kendi were fashionable, and we’re now suffering through an extended backlash, with all kinds of racists coming out of the woodwork.

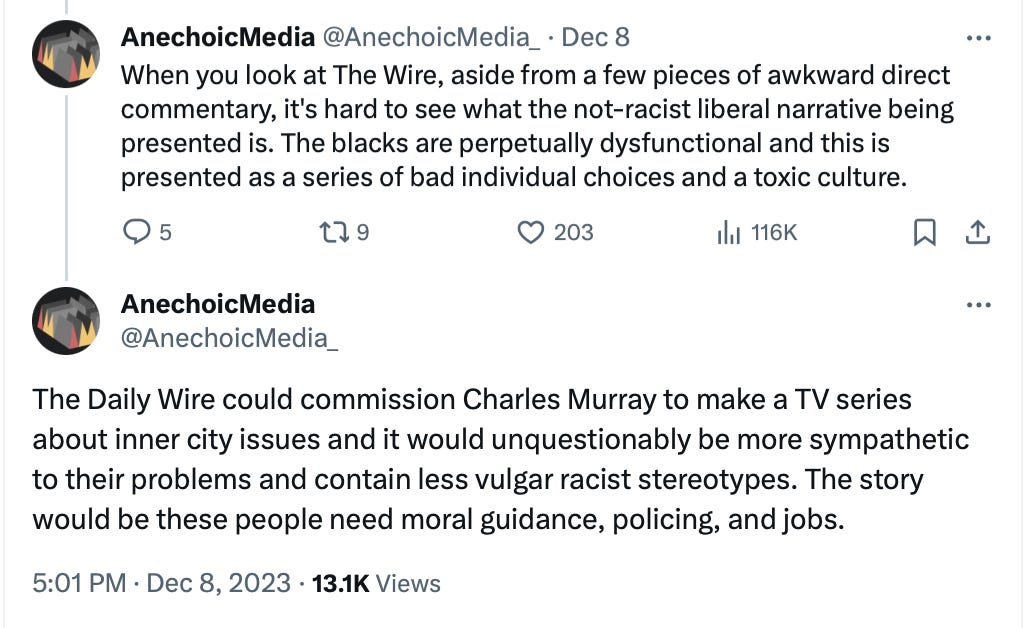

But what really brought home exactly how deep into obscurity his brand of progressive ideas had sunk were these offhand remarks about The Wire and its allegedly non-liberalness. This person genuinely can’t conceive of an account of urban dysfunction that is neither Kendi nor Charles Murray and is confused as to why this Bush-era show was considered progressive.

Part of the story here is that The Wire is well-made art, and different people can see different things in it. It’s pretty clear, for example, that the show’s creator, David Simon, thinks the Tommy Carcetti character is a bad guy. But in my self-consciously pragmatic view of politics, I think Carcetti is basically in the right, and the show is crafted skillfully enough that people can have different perspectives on that character, just as they would a politician in the real world.

But most of all, The Wire is a depiction of Wilson’s view of the crisis in urban America. That’s how I saw it when I watched the show, and as it turns out, that’s how Wilson saw it, too.

In 2009 he said the show “has done more to enhance our understanding of the challenges of urban life and the problems of urban inequality than any other media event or scholarly publications, including studies by social scientists.” That seems a little overstated to me; I think the social science (including Wilson’s) actually matters a lot. And his ideas continue to be relevant.

Some big ideas

Part of what’s great about Wilson is that he has really good book titles, and they sum up quite nicely his two key ideas.

One is “The Declining Significance of Race,” and the other is “The Truly Disadvantaged.” The point about the declining significance of race isn’t that race doesn’t matter or there’s no such thing as racism or that racial equality has been achieved. Rather, Wilson means that contrary to the tenor of many recent conversations in American life, race-as-such has come to matter a lot less than it used to. It used to be the case that a Black attorney or a Black medical doctor or a Black Harvard graduate was living in a completely different social reality from a white attorney or a white medical doctor or a white Harvard graduate. And that’s just not nearly as true today. Race hasn’t lost its social salience or significance, but it’s not overwhelming in the way it once might have been. A person who has gone to a selective college and entered a profession is going to have a meaningful amount in common with his classmates and colleagues of another race, alongside some meaningful differences.

And this is something you see in The Wire.

It’s just not true that “the blacks” are “perpetually dysfunctional.” There are huge differences between the different African-American characters based on their class, educational background, interests, and opportunities in life. It’s not that Cedric Daniels or Tony Gray have nothing in common with Marlo Stanfield or Avon Barksdale, but they really are coming from different worlds, even within the city of Baltimore. There are people who, regardless of skin color, are in a practical sense integrated into the power structure and civil society of mainstream American life. The nature of the crisis in the city isn’t that everyone is excluded in the way that they would have been 50 years earlier, it’s that despite the declining significance of race, there’s still a huge excluded population.

And it’s that population that is the truly disadvantaged — the kids you see in school in Season Four, but also the young people involved in gangs and drugs in the earlier seasons. Despite the end of Jim Crow and meaningful elements of both de jure and de facto segregation, a huge swathe of Baltimore society is totally cut off.

When work disappears

Season Two of the show, which focuses on a group of downwardly mobile white people, illustrates one of Wilson’s other major themes from “When Work Disappears: The New World of the Urban Poor.”

Wilson argues in that book that deindustrialization and the suburbanization of work, coming on the heels of Civil Rights success stories, left a lot of African-Americans trapped in a dysfunctional situation, right as many others were ascending to the middle class. The Wire illustrates the aftermath of that process in Baltimore’s poor Black neighborhoods, but also depicts it as an ongoing process that can afflict white communities as well in the decline of the port.

A few things happen when work disappears — one is just that people in a very literal sense get less money, but there are also broader consequences for society.

Nick Sobotka has a daughter. But he doesn’t live with his daughter, and he’s not married to his daughter’s mother. Instead, he lives in his parents’ basement. He tells his girlfriend that “as soon as I start getting more hours, the first thing I do is get my own place.” But he never gets those hours.

Without steady, blue collar work available, he’s not playing a conventional provider/husband/father role. A lot of men in those situations turn to high risk criminal undertakings. And when young men start going down that path, some of them do get money. But a lot of them end up dead or incarcerated, and that has second- and third-order consequences. For starters, the dead or imprisoned “missing men” create a skewed gender balance that encourages polygynous behavior and low-commitment, unstable relationships. Kids (especially boys) growing up without consistent engagement from their fathers are more likely to act out and misbehave. Raj Chetty and his co-authors find that the presence or absence of fathers makes a difference at a neighborhood level to boys’ outcomes. The white working class community in Season Two is just taking the first steps down that road to dissolution, but things are clearly heading that way.

Senator J.D. Vance, before he took his Trumpist turn to get elected, liked to talk about the application of Wilson’s ideas to white “rust belt” communities where work — specifically steady, male-oriented blue collar factory work — started to disappear after the publication of Wilson’s book. Vance’s original take on Trump, of course, was that backing Trump was a sort of lashing-out from dysfunctional communities that were suffering from very real problems:

The great tragedy is that many of the problems Trump identifies are real, and so many of the hurts he exploits demand serious thought and measured action—from governments, yes, but also from community leaders and individuals. Yet so long as people rely on that quick high, so long as wolves point their fingers at everyone but themselves, the nation delays a necessary reckoning. There is no self-reflection in the midst of a false euphoria. Trump is cultural heroin. He makes some feel better for a bit. But he cannot fix what ails them, and one day they’ll realize it.

I’m not sure when or how that realization arrives: maybe in a few months, when Trump loses the election; maybe in a few years, when his supporters realize that even with a President Trump, their homes and families are still domestic war zones, their newspapers’ obituaries continue to fill with the names of people who died too soon, and their faith in the American Dream continues to falter. But it will come, and when it does, I hope Americans cast their gaze to those with the most power to address so many of these problems: each other. And then, perhaps the nation will trade the quick high of “Make America Great Again” for real medicine.

On exactly those lines, I’ve always thought Trump’s core base sort of resembles a white version of the people who loved Marion Barry here in DC or the fictional Mayor Royce in Baltimore. Those are politicians who are good at speaking to people’s sense of marginalization, but not that good at running the government and actually fixing things. These dynamics emerge not from material deprivation as such, but from a kind of community destabilization. And while there absolutely is a racial specificity to this as a result of the long arc of American history, it’s not “about race” in the sense of here-and-now discrimination.

You fix things by fixing things

Way back in 1990, Wilson wrote an important article for The American Prospect arguing that Democrats should “promote new policies to fight inequality that differ from court-ordered busing, affirmative action programs, and antidiscrimination lawsuits of the recent past.”

He argued that those kind of policies, by triggering white backlash, put Republicans in office and left African-Americans, especially the truly disadvantaged, much worse off than they’d be with race-neutral economic programs. In a 2011 followup piece, he argued that in light of shifts in the American political landscape, you didn’t need to tread quite as carefully and endorsed things like the Harlem Children’s Zone that are specifically targeted but that continue to “reinforce the belief that the allocation of jobs and economic rewards should be based on individual effort, training, and talent.”

To me, though, the most important lesson of Wilson’s work is the importance of actually wrestling with the details of problems.

I started this post with someone on Twitter observing that The Wire depicts the truly disadvantaged as needing “moral guidance, policing, and jobs.” They characterized that as a conservative view, and certainly the emphasis on moral guidance has a rightward inflection. But would conservatives, in fact, favor a significant investment in providing better public services and employment in Baltimore? I’m pretty skeptical. There’s a reason that every Trump administration budget submission called for cuts in federal policing grants. The reason isn’t that Trump hates cops, but that Republicans hate giving money to poor cities. And they definitely don’t want to finance inner-city job creation schemes. Any effort to meaningfully invested in better public services and better employment opportunities in high-poverty communities would be a form of progressive policymaking.

But this person is correct to note that it would be a very different form of progressive policymaking than one that focuses on anti-racism programming or telling people that being on time is white supremacy.

On some of this, we actually have a really strong story in recent years with the Black-white wage gap sinking to its lowest level on record as the employment rates converge.

Of course, problems exist. A lot of people have overcorrected from “educational outcomes are largely explained by selection effects” (which is true) to “educational outcomes are entirely explained by selection effects.” In fact, lottery studies show charter schools outperforming traditional public schools by increasingly large margins and particularly doing so in urban areas. Unfortunately, as the evidence for charter schools has gotten stronger, both parties have walked away from them. And while crime has fallen a lot in 2023, that decrease followed a huge increase in 2020.

We need to be firing on all cylinders: better job opportunities, safer streets, better schools, with all of these factors reinforcing each other. This is more difficult than just spotting disparities and applying the label “racism” or appointing endless rounds of reparations commissions that everyone knows aren’t really going to do anything. But it’s difficult because actually solving hard problems is hard.

I don’t have any particular information about his personal health, but I gather that even though he hasn’t passed away, he’s been unwell these past few years, which is unfortunate.

The day after Trump got elected, I went to a panel discussion at Harvard about race in America, where one of the panelists was William Julius Wilson. He was unforgettable.

Some details that stick out to me now: he criticized the BLM activists who pushed Bernie Sanders away from a race-neutral economic message; he criticized social scientists who refused to include data on poor whites alongside poor minorities.

But the most memorable moment was his speech. He mentioned his support for a jobs program in Chicago, and rather than asking the audience to take it on faith, he asked the other panelists if he could have ten minutes to present his case. They gladly agreed. He then walked up to the podium with a binder in hand (I don't know where he got it), and his argument was just overwhelmingly forceful -- not because the conclusions sounded nice, but because his evidence was clearly solid, the result of decades of serious research.

I wish more of my fellow academics would take a page from Prof. Wilson's book and follow the evidence, rather than confabulating arguments to fit trendy conclusions.

"Trump’s core base sort of resembles a white version of the people who loved Marion Barry here in DC." My brain went "aha!" after reading this. A very useful comparison that helps me think more critically about both situations.