Why teacher evaluation reforms flopped

The strange death of education reform, Part V

This is part five of an ongoing series. Check out part one on the nature of the education reform movement, part two on the rise and fall of the achievement gap, part three on the successes and failures of charter schools, and part four on the right’s embrace of unregulated privatization.

I can’t believe I’ve gone this far in the series without discussing what was probably the single most important component of Obama-era Education Reform: the large-scale effort to shift teacher compensation and teacher evaluation from a system that was very focused on seniority and credentials to one focused on teachers’ measured ability to generate learning gains for students.

Obama was not only convinced by this strategy on the merits, but his administration was also empowered in a very unusual way to implement this change.

This was in part thanks to the Great Recession, which left state and local governments short on money and the macroeconomy in need of fiscal stimulus. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act allocated money for a grant program called “Race to the Top” that, instead of giving federal money to school systems based on some formula, granted funds based on the extent to which schools implemented Department of Education-approved reforms. It was also in part a somewhat peculiar legacy of the original No Child Left Behind law, which deliberately gave states unrealistic proficiency targets and required non-compliant states to obtain “waivers” from the federal Department of Education.1

The nexus of RTTT and the NCLB waivers gave Arne Duncan unusual influence over K-12 policy (which is typically more of a state and local matter), and Obama empowered Duncan to wield that influence fairly aggressively — especially to push states to adopt quantitative teacher evaluation systems.

This was politically dicey. Teachers unions hated it, and while rank-and-file Democrats never turned on Obama over his advocacy for this idea, the dispute drove a lot of intra-party tension and organizing. A lot of people who are today firmly anchored in the progressive wing of the Democratic Party don’t realize (or don’t remember) that downstream disputes about teacher evaluation 10 to 15 years ago were the genesis of so much factionalism, but they were. At the same time, while this cause had a degree of bipartisan support, it wasn’t really something Republicans or the conservative movement leapt to give Obama credit for. Rather than right-of-center people praising Obama for taking on the unions, conservatives generally negative-polarized away from their belief in the reform project, leading to today’s revived interest in vouchers.

If it had all worked out as intended, we would today see this as a major pillar of the Obama legacy — ARRA might not have been large enough to fully close the output gap, but it was large enough to drive systematic and beneficial change in American education.

The unfortunate reality though is that while there are some teacher evaluation success stories, these reforms did not on the whole generate great results. The upshot is that a ton of political capital was poured into something that didn’t work, the energy for reform dissipated, and a tremendous opportunity was lost.

The 10,000-foot case for evaluation reform

As I’ve argued before, in politics it’s really helpful to be right about everything all the time. Unfortunately, Obama and his allies were wrong about this, and I was, too. The upside, though, is that I feel like I can describe pretty clearly what the reformers were thinking.

The basic point is that when it comes to setting teachers’ salaries (or deciding who gets laid off during a budget crisis), you have to pick some system. You could pay everyone the exact same amount (or do layoffs randomly), but that would still be a choice. And I think paying every teacher the exact same amount would probably be a mistake. Instead, districts typically pay teachers based on seniority, with extra pay based on their possession of graduate degrees. Because of the way pension and health benefits work, a veteran teacher is more expensive to have on the payroll than a rookie, even if their salaries are identical. So in practice, the system is even more weighted toward seniority than the salary schedule alone would suggest. Meanwhile, many systems operate on a “last in, first out” system for layoffs, meaning the most junior teachers are the ones who have to go in the event of a budget crisis.

You can model this as just union clout, but I think many who support this system have a good-faith belief that seniority serves as a rough proxy for teacher skill. That’s even clearer for the graduate degrees — giving people extra comp for extra credentials makes no sense unless you think the credentials are a good proxy for quality.

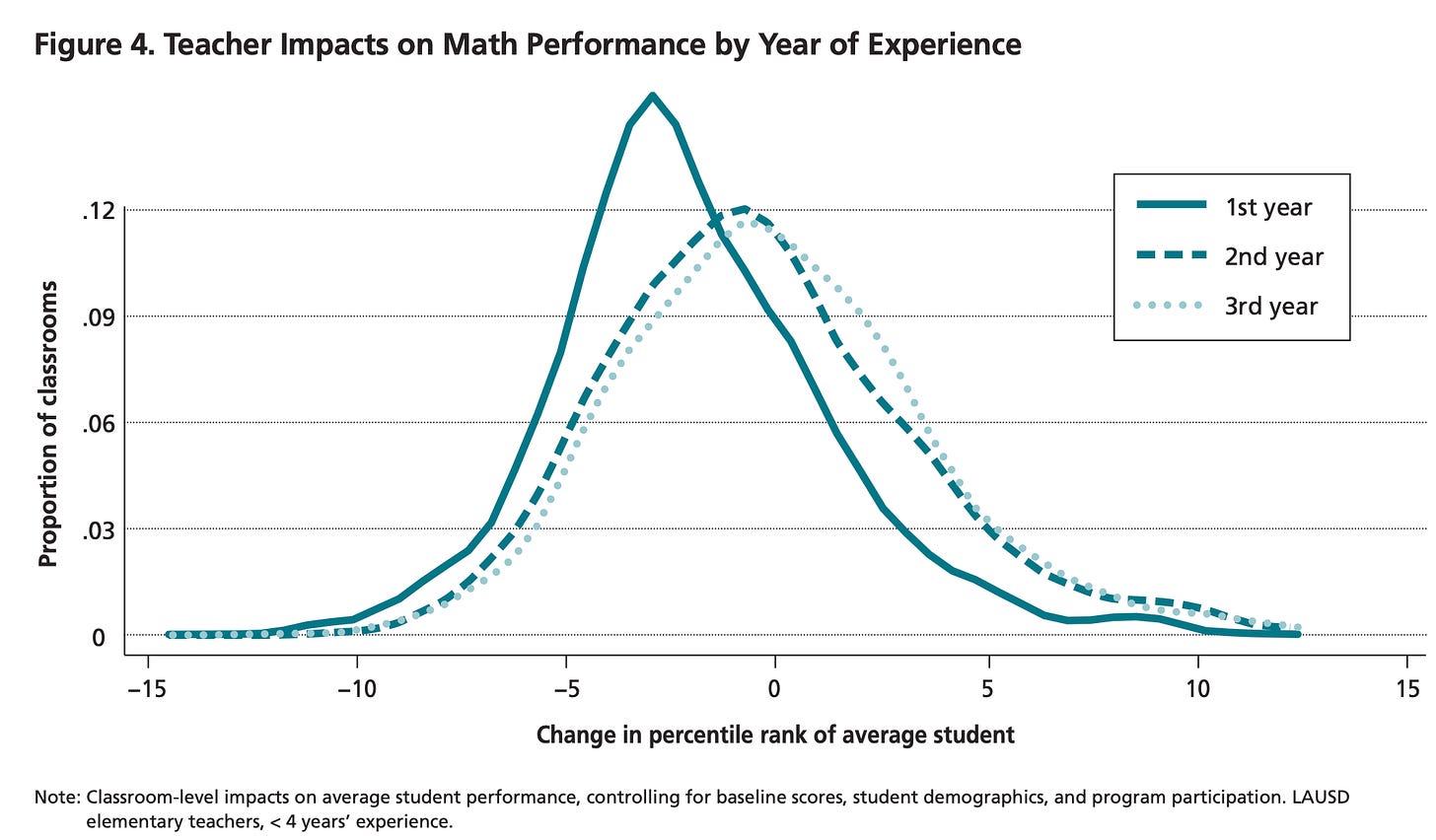

In reality, though, seniority is a pretty weak proxy for quality. In a very influential paper published in 2006 by the Hamilton Project at Brookings, Robert Gordon, Thomas Kane, and Douglas Staiger argued that the positive impact of experience on performance plateaus fairly rapidly.

The research on paying teachers extra for getting Master of Education degrees is, if anything, much clearer — these degrees do not help teachers become more effective, in part because the incentives are obviously screwy. Teachers are strongly incentivized to get the degrees whether or not the degrees are valuable, so universities compete in the marketplace to make the degrees as easy to obtain as possible. And as any teacher could tell you, that is not a good way to teach anything useful to anyone.

That’s what made the idea of switching to a system that emphasizes measured effectiveness so compelling.

Is it straightforward to measure what makes a great teacher? Of course not. Are there problems and shortcomings with value-added measures based on test scores? Sure. At the same time, a highly imperfect proxy still seems much better than a proxy that definitely doesn’t work well, like seniority. And the master’s degree thing is worse than useless — the teacher ends up with less than 100 percent of the raise because some of the money goes to pay off the student loans that financed the useless degree.

Surely we can do better than this.

It’s hard to do better

I think that we can, in fact, do better, and the teacher pay reforms that Washington, D.C. enacted during this era have had some clear benefits.

But in terms of the big national push for compensation reforms, the news is bad. That’s the conclusion of a recent and convincing paper co-authored by Joshua Bleiberg, Eric Brunner, Erica Harbatkin, Matthew Kraft, and Matthew Springer:

Federal incentives and requirements under the Obama administration spurred states to adopt major reforms to their teacher evaluation systems. We examine the effects of these reforms on student achievement and attainment at a national scale by exploiting the staggered timing of implementation across states. We find precisely estimated null effects, on average, that rule out impacts as small as 0.015 standard deviation for achievement and 1 percentage point for high school graduation and college enrollment. We also find little evidence that the effect of teacher evaluation reforms varied by system design rigor, specific design features or student and district characteristics. We highlight five factors that may have undercut the efficacy of teacher evaluation reforms at scale: political opposition, the decentralized structure of U.S. public education, capacity constraints, limited generalizability, and the lack of increased teacher compensation to offset the non-pecuniary costs of lower job satisfaction and security.

I really like this paper because it not only presents a provocative result but offers a good explanation for what went wrong. Federal officials saw local reforms that seemed to be producing good results and decided to create a financial structure whereby the federal government would try, via the states, to make localities adopt similar reforms.

But not only do education interventions in general have an annoying habit of failing to work at a large scale, but this particular effort was beset by huge problems of political implementation.

Lots of the state-level politicians thought these evaluation systems were a good idea, of course. But the marginal elected official in these jurisdictions often didn’t think this was a particularly good idea, and only went along with it because they wanted the RTTT money. That meant there wasn’t a strong state-level political coalition that really wanted to overhaul the teacher personnel system. And this was atop another implementation layer of school boards (or occasionally mayors) who almost certainly didn’t want to change things. This then filtered down to another layer of implementation where principals were suddenly dealing with teachers who didn’t like being subjected to a new evaluation framework. Meanwhile, a range of actual practitioners (including some fervent reformers) has emphasized to me that reformers at the time tended to ignore the fact that most principals in schools with challenges really, really hate needing to fill vacancies. There isn’t some huge line of skilled teachers looking to take jobs in high-poverty schools.

The last line in the quote above about “the lack of increased teacher compensation to offset the non-pecuniary costs of lower job satisfaction and security” is really important in my opinion.

A key linchpin of the D.C. merit pay efforts is that average compensation went up by a large amount — and is only partially undermined by the high cost of D.C. housing. Every teacher, every year, needs to make a choice between “keep teaching” and “change careers.” The goal of compensation reform is to make the above-average teachers marginally more likely to keep teaching and the below-average teachers marginally more likely to change careers. But if teachers on average find the assessment process annoying and the reduction of job security troubling, then you’re making retention of average teachers harder and undermining the whole process.

Revisiting the original recommendations

The Gordon/Kane/Staiger paper I mentioned earlier was very influential on my thinking. And it’s not just me. The Hamilton Project, in the late Bush years, played a major role in developing the policy agenda of what would turn out to be the Obama administration. Then-Senator Obama was even a featured speaker at Hamilton’s launch.

I think it’s fair to say that the paper wasn’t just one of the research documents that supported the Obama administration’s approach; it was, in a sense, the intellectual blueprint for the whole thing.

Still, it’s worth saying that this policy agenda was conceived during a different set of circumstances than those under which Obama became president. He says in the talk above that “when you keep the deficit low and our debt out of the hands of foreign nations, then we can all win,” and the policy panel that followed really focused on deficit reduction. Democrats in the mid-Bush era were not expecting the Great Recession, a huge collapse in aggregate demand, soaring unemployment, and ultra-low interest rates. They believed the Bush policy mix of tax cuts, wars, and Medicare expansion was unsustainable and that it would fall on them to replace it with something more responsible. By the same token, Obama name-checks Gordon as one of the Hamilton people “I have stolen ideas from liberally.” But Gordon’s paper does not propose using federal stimulus funds to try to strong-arm states into changing teacher evaluation policies, in part because the whole idea of doing a big federal stimulus wasn’t on the radar.

What they wanted the federal government to do instead was pick up the tab for “up to ten states” to create a system that would offer bonus pay to highly effective teachers who were willing to work in high-poverty schools while denying tenure to highly ineffective teachers.

That’s similar enough to RTTT that you can see how one idea became the other. But it’s also genuinely different — Gordon proposed, essentially, a subsidy to a handful of states whose political leaders were genuinely enthusiastic about reform, with the reform in question designed to take nothing away from veteran teachers. It’s a policy change that is designed to generate a much higher level of top-to-bottom alignment, from teachers to principals to district leaders to state-level politicians. The hope, obviously, was that the reforms would prove to be a huge success, which would generate pressure for further adoption.

The other important plank of Gordon/Kane/Staiger was reducing barriers to entry in teaching. They cite data indicating that while traditionally certified teachers are better on average than uncertified ones, the difference is small with plenty of overlap. The idea was that by pairing certification reform with tenure reform, you’d cycle through more cohorts of rookie teachers faster, weed out the least-effective ones, and over time raise average teacher quality. And you could achieve that without doing anything negative from the standpoint of veteran teachers.

Because of the Great Recession, we ended up in a situation where districts weren’t hiring new teachers or creating new bonus programs. There was instead a lot of emphasis on using effectiveness evaluations to structure layoffs, which makes sense conceptually but is a clear and present danger to veteran teachers, and the point of RTTP was to tempt jurisdictions that didn’t particularly want to do compensation reform to do it anyway.

I think the hope was that this would bring reform to scale much faster.

Instead, it generated tons of ill will while creating a very strong socio-psychological connection between the evaluation movement and a period of severe education austerity in which budgets were slashed, jobs were lost, and inflation-adjusted salaries fell. And it was from within the union backlash milieu that we first started hearing from Ibram X. Kendi that the idea that an achievement gap exists is racist and that we can’t try to evaluate teachers based on student test performance because standardized testing is also racist.

Pitfalls of change

As I mentioned above, I was a true believer in this particular reform idea.

And I still believe that the 10,000-foot version of it is correct. If anything, I’m more focused than ever on the role that screwy compensation practices play in supporting rent-seeking graduate schools of education and in incentivizing them to operate as highly ideological enemies of sound social science and pedagogy. One potentially promising compensation reform proposal is to simply eliminate all new graduate degree bumps on a forward-looking basis and plow the savings into higher base pay across the board. This would have only minor educational benefits, but down the road it would have good political economy benefits.

More broadly, though, my thinking about the other great municipal workforce — cops — is greatly shaped by my understanding of what did and didn’t work here.

My points about the spatial misallocation of police officers are directly parallel to the Gordon/Kane/Staiger points about the utility of paying bonuses for highly effective teachers who are willing to take on the most difficult assignments. The discourse about “merit pay” flew off in a different direction, but the basic idea was never intended to be anti-teacher — it’s simply harder to teach classrooms full of kids who are dealing with a lot in their lives and whose parents are less likely to have the bandwidth or the financial resources to participate actively in their education. But the system as a whole does not serve its intended goals if valued teachers all self-select out of those assignments, leaving the toughest jobs to a mix of rookies, idealists, and people who’ve washed out of other schools.

Similarly, whether you’re talking about cops or teachers, if you want to hold people to a higher standard you need to be willing to spend money on higher pay and to think hard about recruiting pipelines.

The next, and probably final, entry in this series will focus on something that, based on the arc of ed reform, I am both hopeful and concerned about: I’m inclined to support the new wave of enthusiasm for phonics and “the science of reading,” but I also worry it will turn out to be another example of something that’s hard to bring to scale in a decentralized system.

The story behind the specifics of this law is interesting, but I have to confess that it was before my time and I don’t fully understand it — and the people I’ve spoken to who were involved have somewhat conflicting accounts. In a nutshell, a new law was expected to supersede NCLB at some point and address this, but the timeline for writing a new K-12 bill slipped all the way to 2015, so the waiver era lasted a long time.

I always wanted to be a teacher. Somewhere along the way I realized engineering would be more challenging and rewarding, and went that route instead. But I was maybe 5 years out of college when all this stuff really came to a head. I was not loving engineering so much and I recall thinking that if they wanted to “fix” the teaching profession, whatever they did, it ought to make it more appealing/accessible to people like me. (Egocentric, right?) To this day, if they had a program where, say, I could do a 3-month boot camp and then start teaching high school Physics and Calculus and STEM at half the salary I make now, I’d jump on it. But the hoops are too big and the pay is too low.

The low point of the push for teacher evaluations in NYC came when the Bloomberg administration released the evaluation results of all the public school teachers to the press, and the NY Post did this story about “the worst teacher” in the city, printing her name and picture for all to see:

https://nypost.com/2012/02/26/queens-parents-demand-answers-following-teachers-low-grades/amp/

It later came out that this teacher’s students were recent immigrants with special needs who did not speak English, so they had some academic challenges to say the least, and couldn’t possibly have scored well on the state exams that made up a big part of the evaluation.

https://www.politico.com/media/story/2012/03/fellow-teachers-come-to-the-defense-of-pascale-mauclair-singled-out-as-the-worst-by-the-post-000338/

The NY Post didn’t retract the story or add any context, and to this day if you google the teacher’s name this story shaming her is the first thing that comes up. It was pretty much impossible to get teacher buy-in for the system after that.