When the "culture war" was about religion

The past and future of the United States of Canada vs. Jesusland

Back in 2005, then-president George W. Bush held a press conference in Texas where he was asked a question about intelligent design, a once-faddish account of the origin of species that some people felt should be taught alongside or instead of the standard Darwinian account of evolution.

“What are your personal views on that,” the reporter asked, “and do you think both should be taught in public schools?”

Bush responded that when he’d faced this topic in the 1990s as governor of Texas, “I said that, first of all, that decision should be made to local school districts, but I felt like both sides ought to be properly taught ... so people can understand what the debate is about.”

The journalist pressed him: “So the answer accepts the validity of ‘intelligent design’ as an alternative to evolution?”

And Bush said, “You're asking me whether or not people ought to be exposed to different ideas, and the answer is yes.”

This controversy — which raged for years as a top-level culture war issue — now seems to have been forgotten by many. It’s vanished so completely from public debate that when I asked Milan for help researching the intelligent design controversies of the aughts, he didn’t believe that this was a real thing. But it was extremely real and in part a sign of how different the political dialogue was back in the Bush years.

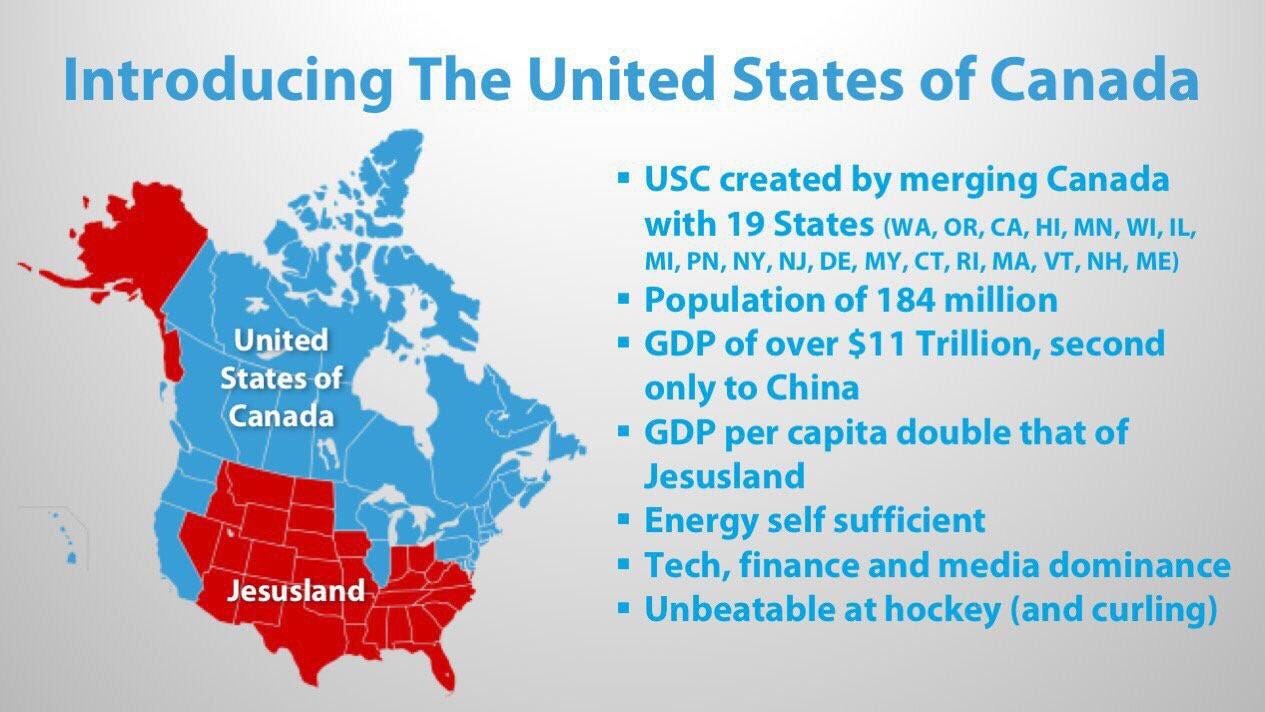

One particularly vivid example is that while Donald Trump’s victory in 2016 led progressives to focus on the prevalence of racism among the American electorate, the dominant progressive response to Bush’s re-election in 2004 was this viral map depicting the Bush states as “Jesusland.”

Note that this way of conceptualizing the red/blue split as about religion rather than racism actually involved different states. Back in 2005, the racist, immigrant-hating voters of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania were solid citizens of the United States of Canada, while Nevada, New Mexico, Virginia, and Colorado were lumped in with the Jesus freaks. And it’s a bit amusing given my relative positioning among progressives today, but one of my big early-career hot takes during the Bush presidency was that the media tended to understate the significance of race in American politics, ignoring, for example, the large number of religiously observant Black and Hispanic Kerry voters.

I’m not a big fan of mining history for analogies to prosecute arguments about the present. But I do think that if you want to understand the current trajectory of American politics, you need to start with an accurate sense of the prior situation. The waning of religion-forward strife is implicated in a lot of present-day trends, including the shift of many white working-class northerners into the GOP, but also recent Republican gains with Black voters, some of the tumult you see among newly right-coded intellectuals, and a backlash to “sex-positive” feminism forecast by Katherine Dee and Michelle Goldberg.

The evolution wars, revisited

The evolution wars were on some level similar to contemporary debates over teaching about race in public schools.

Christopher Rufo, the leading popularizer of the anti-CRT movement, started his CRT work at a now-obscure conservative think tank called the Discovery Institute. But Discovery was anything but obscure 15-20 years ago. A couple of months before Bush addressed the intelligent design issue, the New York Times wrote about Discovery proudly announcing that a new intelligent design film would be premiering at the Smithsonian Institute, prompting a backlash and leading the Smithsonian to back out of the deal. That same spring, the Kansas Board of Education held hearings on the incorporation of intelligent design into the curriculum, hearings characterized on progressive blogs as “The Scopes Monkey Trial: Take Two.”

There was also during this period a steady drip of intelligent design legislation introduced in state legislatures: Louisiana, Michigan, Georgia, and Arkansas in 2001; Pennsylvania in 2005; Mississippi in 2007; Florida in 2009. And in 2002, Ohio adopted curriculum guidelines that included “critical analysis” of the theory of evolution.” Texas during this time had a mandate that science classes teach the “strengths and weaknesses” of the theory of evolution, and there were many fights about the contents of their textbooks.

It was never entirely clear to me how this issue was playing politically.

Certainly neither Bush nor John Kerry nor John McCain nor Barack Obama was very interested in discussing the topic. When McCain in a low-key way endorsed teaching intelligent design, intelligent design got very excited. And when Paul Waldman and David Brock wrote a book about how the media was giving McCain a free ride, they characterized non-coverage of his position on this as part of that free ride.

One reason elected officials seemed leery of this topic is that mainstream opinion is kind of hard to characterize. The median voter seems to say that evolution is real but guided by God.

But what does that mean? I’m not entirely sure and I think the voters aren’t either — as Pew found, these numbers move around a lot based on exactly how you ask the question. The point I want to leave you with here, though, is that a large minority of Americans are out-and-out creationists (in the General Social Survey, about a third of people say the Bible is the “literal word of God” as opposed to merely divinely inspired), but we don’t hear as much from them these days and we also don’t hear so much about them. But once upon a time, the fact that many Americans are devoutly religious was a huge subject of discussion.

The secularization of America

Another once-prominent topic of aughts politics that has faded away is the New Atheism movement led by Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, the late Christopher Hitchens, and Sam Harris, the youngest of the foursome and the one with the most influence today.

The difference between New Atheism and normal atheism was that New Atheists wanted to be really vocal about not being religious and published books and manifestos. Part of that was a sense that religion wasn’t just false but actually bad, so we should scold people out of it. And though the United States remains much more religiously observant than most other rich countries, the share of people not affiliating with any religion is rising fast — so fast, in fact, that there were more unaffiliated Republicans in 2021 than there were unaffiliated Democrats in 2006.

This secularization trend has been a huge defeat on its own terms for the conservative movement of the aughts.

But that hasn’t meant the end of conservatism. On the contrary, the political right has simply become a bigger tent that accommodates a wider range of religious views. Andrew Sullivan used to inveigh frequently against “Christianists” but is now more likely to be found denouncing left-wing racial politics. Similarly, Harris — the New Atheism leader — was at the center of a huge controversy more recently about his promotion of Charles Murray’s work on race.1

In 2008, Bill Maher made a movie called “Religulous” dedicated to making fun of religious people, while today he’s more likely to make news talking about how Democrats have gone too far left.

As I wrote when Elon Musk was complaining about this leftward shift, I think it is clearly true that Democrats have embraced some big ideological changes. But I also think a big part of why some people feel more alienated from the left these days is simply that they feel less alienated from the right on religious grounds. And I think this is probably true of the larger political trajectory of the Silicon Valley c-suite class. During the Bush and early Obama years, having a secular-rationalist worldview was strongly left-coded. Today, “arguing about religion” isn’t nearly as much of a thing, and “guy who’s really persnickety about biology is fighting with politics activists” is likely to be fighting about trans women in athletic competitions rather than evolution in high school.

I don’t know how long this new alignment will hold up. The Supreme Court is poised to toss out Roe v. Wade, and Republicans will make serious efforts to ban first-trimester abortions in many places. This is going to be a clear and vivid example of a policy that imposes significant practical harms in the name of an essentially religious (and specifically Christian) conception of moral personhood, and I think it may re-elevate the salience of religion in a now-less-religious country. But for now, religion as such is not as big of a deal as it was back then, and it’s scrambling old alliances.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.