Who are the groups?

Plus good DOGE, message discipline, and the case for an attention tax, all in today's Mailbag

I missed this last week, but apparently, Elon Musk has been telling people that he’s going to do “a lot less” political spending in the future.

Part of Slow Boring’s official case for donating money to Susan Crawford’s Wisconsin Supreme Court race was that the race was not only important for the merits for abortion rights and gerrymandering, but Musk was following up his 2024 spending with a big intervention in the race. I said that I believed if he lost there, he might become demoralized and decide that even though he can afford to make nine figure contributions to GOP campaigns every year for the foreseeable future, maybe he doesn’t want to. That seems to be happening, which I think is good.

And just to toot our own horn for a second, this is part of what I think is valuable about Slow Boring as an enterprise.

A million columnists are doing takes about how Democrats should do this, and Democrats should say that. But there are actually very few media outlets that try to tell you what you can do to make better things happen in the world. Some of that is that an NYT or Washington Post columnist isn’t allowed, ethically, to write things like “Hey, give money to Susan Crawford!” But a lot of it is that I genuinely think way too many content-providers are in the doomscrolling business because doomscrolling is good for business. All any of us can actually do in this world, though, is try to take action and not just gawk. So thank you to everyone who supports a business that tries to do that.

On that note, as usual, the first few questions of the last mailbag of the month are from our GiveDirectly donors. Another huge thank you to everyone who joined in that effort! You can read about how your donations were used here.

Anonymous: After spending my entire 20 year career in big tech, it’s become clear that most of my job will be done by AI in less than 5 years — a change I’m actually fine with, but leaves me grappling with what to do next. I’ve always been interested in technology policy, and it's clear we are on the wrong path at the moment, something I'd like to change.

With a technical background, zero policy experience, and not really being in close proximity to any policy centers — it's unclear where to start. But I’m also in a position where I could do something radical (eg internship or unpaid work for a time).

I've always valued your view on taking concrete, practical steps to achieve goals, so I'd love to hear your thoughts on a mid-career pivot towards supporting broadly positive policy agenda for technology.

I would look into the TechCongress fellowships programs (applications will open next month), which has a program intended for experienced professionals. Beyond that, it’s hard to know what might make sense without knowing more about you and where you align, though I would suggest the 80,000 Hours jobs listings as a good source of potential leads. There’s also the AI Futures Project, if you’re interested in that side of things.

That said, we are also in a mode where the posting-to-policy pipeline has never been stronger. A person with strong ideas who starts tweeting and skeeting and substacking about them has a real chance to catch people’s eyes and start making a difference. Oftentimes, this eventually involves a pivot to launching an organization, but something like The Center for Building in North America (one of the leading drivers of the single-stair apartment revolution) is really just Stephen Smith posting himself into becoming the executive director of a nonprofit with no staff.

Anonymous: What policy topic/area has the greatest gap between what the consensus experts believe and what the public wants? How can we navigate that gap?

I think it’s not a specific policy topic, but I think the answer is the general fact that experts broadly agree that a good way to tackle many problems is “tax the externality, use the revenue to offset other more distortionary taxes, and ease up on inefficient regulatory solutions.” Voters hate this, for whatever reason.

In terms of navigating the gap, I do think that it’s always important to try, as a policy writer, to elevate the public’s literacy on these topics, even if it’s hard to change minds. But beyond that, I’m also always trying to disenchant people with the model that important change needs to come from grassroots movements of highly engaged citizens who induce politicians to pass sweeping policy changes. America faces real problems of long-term fiscal sustainability. A large minority of highly engaged and politically influential people are very concerned about climate change. A largely distinct minority of also highly engaged and politically influential people are very averse to steeply higher capital taxation. There are clearly deals to be done here!

Anonymous: I’m a department chair at a large private university, so I’ve been in a lot of bleak meetings recently about the triple whammy of the endowment tax increase, cuts to NIH and NSF grants, and cuts to Medicaid (which will hit the university’s hospital system). Kneecapping research and making American universities less appealing to highly skilled foreigners seems obviously bad. Assuming that some or all of these actually happen, what are the prospects for reversing them after Trump is out of office? Is this a job for Secret Congress, do we need Democratic control of the Senate, or do we need something like broader public support for R1 higher education? On the last point, I’m sympathetic to calls for “ideological diversity,” for reasons of both political alliances and epistemology, but the actual proposals I’ve seen strike me as unworkable at best — not just because there are not binders full of right-wing (or even right-leaning) academics at the ready, but because so much of the intellectual and practical work of the university is grounded in cosmopolitan values, seeks to lessen inequality of various kinds (or at least is justified as such), and isn’t focused on the kind of direct commercial application that Vance, for example, seems to want. Are we screwed?

I agree with you that this is bad, and I also agree with you that solutions seem a little hard to come by.

I don’t particularly want to pile on and beat up higher education at a time when it’s under assault, but I did often look around at the higher ed landscape in 2020 and 2015, and even 2005, and wonder exactly what it was that America’s professor community thought it was doing.

Faculty were presumably aware five or ten years ago that American higher education relied on a lot of direct and indirect government support. They knew, I think, that conservatives are broadly inclined toward spending less rather than more money. They were aware that the political leanings of academics were well to the left of the political views of the overall American public, and they were also aware that there is no easy non-destructive way to change that. So you’d have thought that there would be a mandate to bend over backwards to avoid giving the appearance of excessive politicization, beyond the truly unavoidable consequences of working in a field where a majority of the human capital is left-wing. To at least try to be welcoming to the minority of faculty with right-of-center politics, or at least a desire to articulate the occasional right-of-center view in the context of overall left-of-center politics.

But that obviously was not how most schools operated, and it’s left higher education in a vulnerable position, because it’s challenging to regain lost goodwill quickly.

That said, over the longer term, I really do think course correction is more workable than you are suggesting. What you say about the difficulties are true, but the actual conduct of universities goes well beyond “not a lot of conservatives work here.” When Harvard announced, as they did in 2019, that they will “hire a cluster of faculty in the area of ethnicity, indigeneity, and migration during the upcoming academic year,” this was clearly an institutional choice to respond to criticisms from the left rather than from the right. That’s not a smart call. Educators and researchers need to push back against MAGA wreckage, and also resolve both publicly and privately to take more seriously the reality that this is a democracy, and institutions asking for public support need to take the sensibilities of the mass public seriously.

Eliot D: Matt repeatedly makes the good point that the lack of a pivot from Biden administration to deflationary economic bills in 22/23 helped sink his popularity. However, doing that pivot (just like with the Obama presidency) would have required the cooperation of a Republican House barely held together by Kevin McCarthy. In hindsight, could Biden have handled the budget/debt limit negotiations to better pivot the economy and in the future how should Democrats make it so that they can respond to the economic situation on the ground if/when they lose the mid-terms?

One thing to remember is that a pivot can have political benefits even if it doesn’t “work” in terms of substantive political outcomes. One major progressive critique of Barack Obama is that he seemed obsessed with “negotiating with himself” in showdowns with congressional Republicans. The point of that, though, was that Obama wanted to make sure that when talks broke down, cross-pressured voters would see Obama as the reasonable one. A fundamental asymmetry that Democrats need to take seriously is that since conservatives outnumber liberals, if the parties polarize perfectly and split moderates down the middle, the Republicans will win.

Biden (and later Harris) ran on budget proposals that would have raised taxes on the wealthy considerably, calculating that alienating a certain number of rich people was a price worth paying for the upside of more revenue.

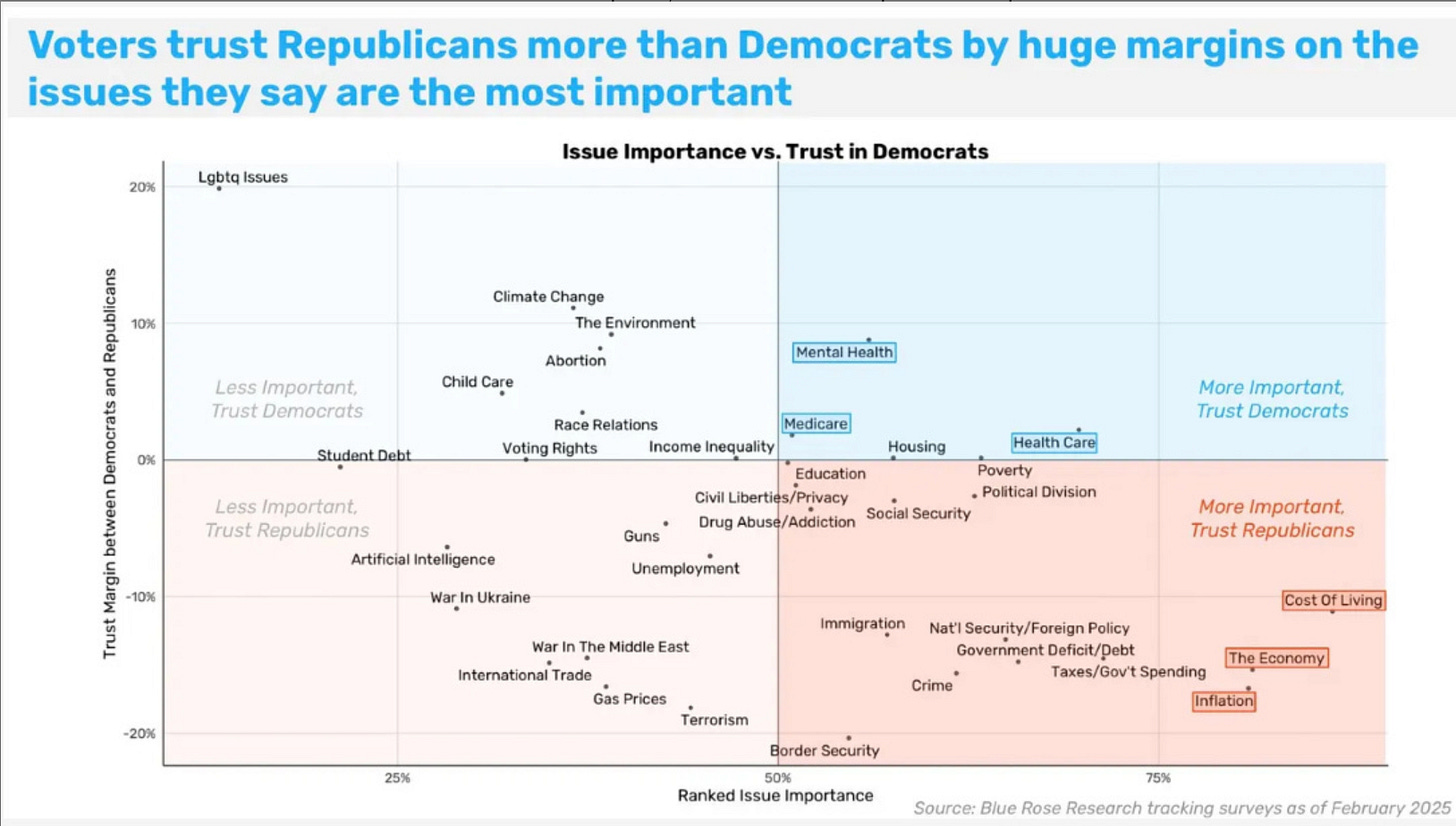

But they then proposed spending the vast majority of that revenue on big new programs when they could have scaled back their new programs and emphasized deficit reduction to reduce inflation and interest rates. When you look at what voters said was most important to them, deficit/debt and taxes and government spending ranked much higher than progressive priorities like child care and student debt, and I'm not sure it made sense to promise new spending initiatives as Democrats’ cost of living solutions, rather than debt reduction to bring down interest rates.

The actual economic situation is always evolving, so I don’t think it’s a good idea to get too locked-in to any particular approach. But my fundamental critique of Biden-era Democrats is that for all the talk about saving American democracy, they did a pretty poor job of practicing the idea that government should be responsive to the desires of the population. If people are telling you that their top priority is the cost of living, you have to find ways to genuinely prioritize that over other things. Trump, of course, is now making the same mistake.

Chris P: I found ai-2027.com to be a compelling and plausible future path for AI. It lays out two futures: one where AI alignment succeeds (the “slowdown ending”) and one where it catastrophically fails. Assuming we navigate the alignment crucible successfully, we'd face the new challenge of governing aligned superintelligence, with potentially immense power resting in a small oversight body. Do you have any thoughts about navigating that transition? What would an ideal governance structure look like from your perspective assuming we got something like the “slowdown ending”?

I will say for starters that while I recommend reading the document, I do not find the scenario they are sketching out to be particularly plausible, mostly because their modeling of President Trump’s decision-making strikes me as wildly optimistic.

If technological advance proceeds on the timeline that they’re talking about, then I think the odds are very high that our staggeringly corrupt president is going to end up selling the country down the river to foreign autocrats and America is cooked. History will record that, in retrospect, voters were highly focused on the short-term cost of living to the point that they put a buffoon in charge of the government at the most critical period of human history and that was lights out for democracy. So I hope the technical forecast is wrong!

By the same token, though, democratic governance of superintelligence seems like an inherently unsolvable problem given American political institutions.

In Germany or Denmark or the Netherlands, no matter what happens in any given election, the result is a coalition agreement among multiple political parties where some centrist party controls the pivotal seat. Under the circumstances “use the power we won to crush our enemies” doesn’t really work as a program. That could hold up even if “the power we won” includes governance over a superintelligence. America has traditionally obtained the non-crushing result thanks to the parties being ideologically diffuse and undisciplined with power decentralized to the states and the judiciary. But decentralization doesn’t work in a world where we are counting on the government to supervise a unitary superintelligence. So it’s doom all around.

Michael H: How do you think policymakers should be approaching AI in the context of schools? Rampant cheating currently seems to be happening in any writing assignment. Is this a question best handled on a school by school basis or does it call for a more broad based approach?

This is too hard a question to answer here.

What I can say is that the whole education system needs to get out of a mindset where they conceptualize the use of AI as “cheating,” and try to devise ways to get people to not cheat. You can devise assignments that involve not using a computer — blue book exams, oral exams — but you also have to devise assignments where the intention and expectation is that students will be using AI. It’s similar to the way calculators have been integrated into math and science courses for a long time now. We don’t just act like calculators don’t exist and then try to stop people from “cheating” by using them.

James C: Why do studios keep making movies with increasingly bloated budgets that almost invariably fail to turn a profit? Is their downside risk limited due to insurance or tax deals (the UK is particularly profligate in this regard)? Was it a product of ZIRP and more modestly budgeted blockbuster movies are on their way?

This seems kind of overstated to me. If you look at the most expensive movies of all time in inflation adjusted terms, you’re mostly looking at successful hit movies. You’re also mostly looking at movies that were produced pre-pandemic at a time when the revenue potential of movies was stronger.

The big exception in terms of both profitability and timing is Fast X, where the poor financial performance of that film seems to be leading to the end of the series or, at a minimum, an effort by Universal to scale things back and get costs under control.

What’s true, obviously, is that a lot of these movies are bad. Even if you’re a fan of the MCU, I don’t think anyone regards “Age of Ultron” as a particularly successful iteration. It’s ranked 27th out of the 36 Marvel movies on Rotten Tomatoes, which I think is generous. “The Rise of Skywalker” is an abomination. But this is a nice thing about movies. There are things you can accomplish with big budgets that cannot be done on the cheap. But there are no scaling laws for cinematic quality, where just pouring more more more into the production makes the movie better. You need a good screenplay!

David: I’d like to see a more in depth description of the groups. Are they all about equally counter productive in your view or are some doing good work while others are more harmful?

The groups are basically uncountable because there are always more groups.

Let me quote three press releases:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.