What to make of Javier Milei's early successes

This is not the first time Argentina's seen a quick boom

Argentina recently released its first quarter economic data showing very strong 5.8 percent year-on-year growth. This led to a lot of football-spiking over Javier Milei’s economic reforms, with many on the right dunking on left-wing economists’ pre-election open letter warning of “devastation” if he won power.

My take is that Milei’s reforms are mostly good.

But I also want to wrestle this discourse under control before it fuels further populist nonsense. I don’t claim any great expertise on Argentine politics, but I think it’s important for everyone to understand the following:

Argentina has experienced a lot of individual quarters of solid economic growth during its 100-year experiment in structural economic decline — there’s a lot of game left to play.

Milei’s successful stabilization of the short-term macroeconomic situation is largely the result of a completely conventional mainstream Neo-Keynesian economics framework endorsed by the IMF and other boring institutions.

After talking nonstop about replacing Argentina’s peso with the US dollar during the campaign, Milei simply has not implemented his signature campaign initiative.

The most interesting lessons to learn here are about the relationship between the populist style of politics and the actual practice of policymaking.

Advocates of populism are often either right-wingers who are absolutely convinced that the essence of populism is doing insane stuff on trade policy or being dogmatically anti-immigrant, or else left-wingers who want price controls on veterinarians or some other hyper-specific policy agenda. But imagine Milei running for president in Argentina by saying, “I’m going to implement austerity budgets and various free market reforms that IMF staff economists like in exchange for some IMF fiscal support and basically try to run a boring technocratic administration.” That probably would have been a huge flop politically.

Mario Draghi tried a version of this in post-Covid Italy with the support of the European Central Bank, and even though his ideas were good, it failed as an electoral program. You need to sell the sizzle in democratic politics.

Milei was fearless about denouncing skeptics of his dollarization program as know-nothing out-of-touch elites, but he was equally fearless in abandoning dollarization when it was unworkable. And while I think it’s much too soon to proclaim the reform agenda a success, it is succeeding for now, and that’s boosting his approval ratings. Now that he’s governing, the political success of the program is going to hinge on his substantive success at managing the economy. Populist vibes or no populist vibes, if you win power, what you want to do is a good job.

Getting the context right

I think it’s important to understand how central a role both outsider vibes and the dollarization proposal played in defining Milei’s political identity.

Back in 2023, the Argentine economy was being destroyed by runaway inflation overseen by a leftist government. Under the circumstances, you would expect to see a big electoral win by the conservative opposition party running on a platform of spending cuts to control inflation.

And, indeed, the conservative opposition party nominated Patricia Bullrich, a former national security minister with a vague track record on economic issues, and she ran for president on a platform of spending cuts to control inflation.

Bullrich’s problem, electorally, is that she was outflanked on the right by Milei, a charismatic outsider who was promising not only fiscal austerity, but the adoption of the US dollar as Argentina’s currency. The conventional wisdom, as encapsulated in this August 2023 profile by Natalie Alcoba, was that Bullrich would win the election, and Milei would end up as a kind of junior partner in implementing the austerity agenda:

In that sense, Bullrich’s metamorphosis can be interpreted as a mirror of Argentine society—a society now exhausted and fed up. Yet how she will respond to greater public appetite for change remains to be seen. Bullrich’s camp has opposed some of Milei’s more radical ideas, such as eliminating the central bank and ditching the peso for the US dollar, but she plans “deep structural changes” that include lifting currency controls “as soon as possible” and trading a system of social welfare that she says “humiliates” people and is riddled with corruption, for unemployment insurance with strict time limits. Even before the primaries, when the polls had suggested that they were in a stronger position, Bullrich’s camp was talking about working with Milei on slashing public spending.

Had this come to pass, I don’t think anyone outside of Argentina would find current Argentine politics to be particularly noteworthy. But instead of Bullrich advancing to an easily-won second round matchup with the leftists, she ended up finishing in third place, with Milei advancing to the runoff against Sergio Massa and beating him easily. This triumph of an outsider candidate who’s conversant in contemporary social media and wired into international right-wing populist politics made Argentina a really interesting story. But in terms of policy programs, “Argentina needs to cut spending to get inflation under control” wasn’t the interesting, radical, outsider idea that captured the public’s imagination. That was the platform of the boring third-place finisher Bullrich.

In office, Milei has pursued a program of aggressive spending cuts to drastically reduce Argentina’s budget deficit and end the central bank debt monetization that was fueling inflation. But he has not replaced the peso with the US dollar.

I’m being pedantic about this because I want to emphasize that “Argentina needs spending cuts” was not some kind of outlier notion that defied conventional wisdom.

It’s true that the Guardian ran that letter from 100 economists. But there are a lot of economists in the world. The American Economic Association has 23,000 members, and most economists aren’t American. Thomas Piketty is famous, but he’s an outlier in the economics profession in both his methods and his views. The Guardian writeup of the letter also touted Branko Milanović and Jayati Ghosh as signatories. These are, again, smart people, but also self-conscious left-wing outliers in the field. It’s just not the case that the conventional wisdom among economists held that spending cuts were a bad idea for Argentina. I’m not some kind of far-right fiscal superhawk, but when I wrote about Argentina in 2023 I also said they needed fiscal austerity. They just clearly needed fiscal austerity. This was, in fact, so clear that Massa was also promising fiscal austerity — campaign season articles like “Massa's gradual approach versus Milei's radical plans” ran in the Buenos Aires Times.

What Milei has done

Beyond the chainsaw stunts and populist atmospherics, Milei’s actual policymaking has been fairly conventional, albeit drastic. He has not tried to do what Massa was proposing and sugar-coated austerity with a lot of gradualism or elaborate efforts to shield the poor from hardship. Low-income Argentinians whose living standards had been ravaged by inflation ended up even worse off last year in the face of spending cuts. The unemployment rate rose.

In exchange for his decisiveness in this regard, he secured IMF support for a bailout/loan package, which has made it easier to continue financing the now-smaller budget deficit.

This austerity imposed very real costs on people, but also had a lot of benefits. The central bank is no longer printing money to cover the deficit. This has helped bring down inflation. It also means that since Argentina is no longer relying on funny money, the government has been able to relax currency controls and the use of dual exchange rates. Along with exchange rate liberalization, he’s also cut tariffs.

Argentina’s inflation is still incredibly high by American standards. If you look at the headlines, something like inflation ticking up to 1.9 percent in June from 1.5 percent in May may not sound so bad, but that number is a measurement of inflation on a month-to-month basis rather than year-over-year. So that 1.5 percent inflation rate is more like what we would call 17-18 percent. But the reduction is still incredibly meaningful. Pre-Milei, inflation was so high that it wasn’t just an annoyance to consumers or a source of hardship, it meant that trying to make guesstimates about future inflation trends was a dominant consideration for all kinds of businesses. Inflation is still much higher than is ideal, but it’s low enough that businesses can focus on business.

As a result of this overall regularization of the macroeconomic situation, Argentina is now enjoying a little surge in business investment. Foreigners aren’t deterred by exchange rate rules, and domestic entrepreneurs can focus on their businesses.

Combine this with scrapping rent control to bring more apartments onto the legal market, and deregulating prices in everything from airlines to maritime transport, and you’re left with a much more normal economy. This is roughly the opposite of the left-populist notion of addressing the high cost of living by doing price controls. But it’s also not some exciting new right-populist synthesis. It’s standard technocratic economics — “neoliberalism,” if you will — that’s ditched the signature outsider policy proposal (dollarization) and focused on expert-approved measures.

The hundred billion peso question

This, to me, all seems good. I believe in a market-oriented economy plus a generous social welfare state. Milei’s regulatory moves are unambiguously good. The spending cuts are less good, but were necessary to get inflation under control. Hopefully, if Argentina enjoys several years of macroeconomic stability and steady growth, they will be able to afford a higher level of spending on a social safety net. But the government needs to be bounded by macroeconomic reality.

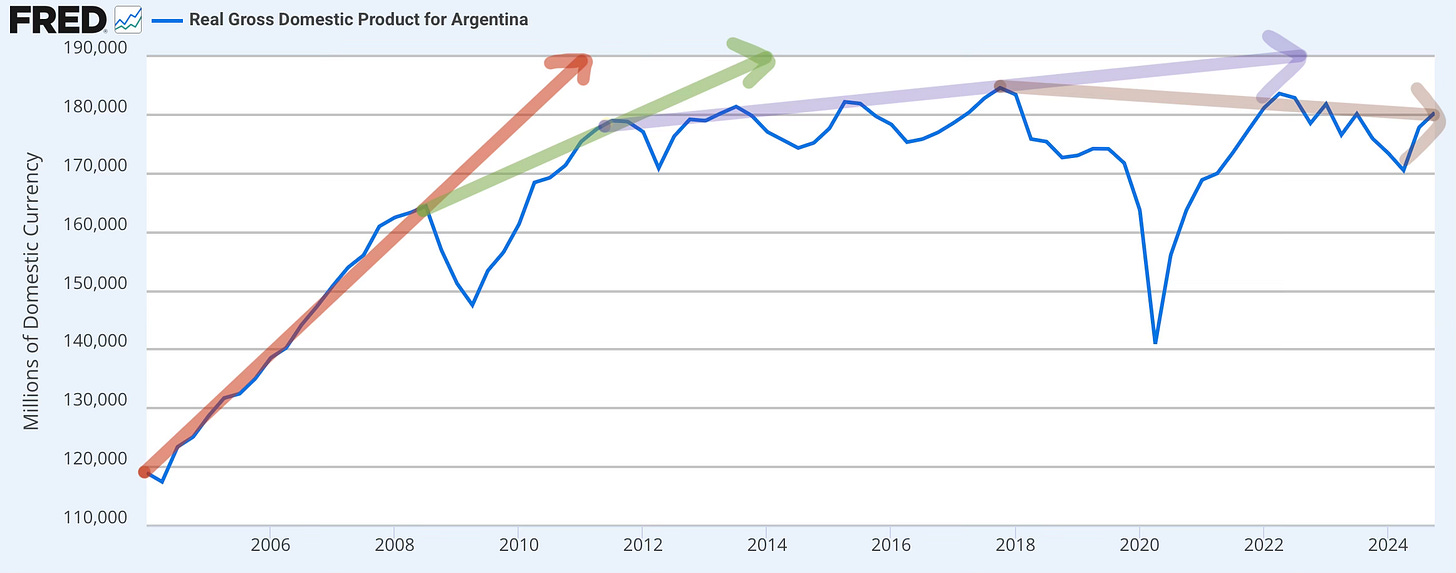

Speaking of macroeconomic reality, though, the huge cautionary note I would sound about all of this is that it’s not like Argentina has never enjoyed a good year of economic growth. If you look at their 21st-century track record, things were going okay for a fifteen year span before falling into crisis. On a time frame of a century or more, Argentina’s growth record looks bad but there have been lots of good spots along the way.

That early red line of the Argentine economy growing like a rocket ship is particularly important to note.

Argentina suffered a massive depression from 1998-2002 because a prior political regime insisted on pegging the peso to the US dollar as an anti-inflation measure. The peg required constant balanced budgets regardless of the macroeconomic situation and, like the gold standard in 1929-1933, meant that a negative shock to aggregate demand turned into an endless downward spiral. The Kirchner family became the dominant force in 21st century Argentine politics because they were the ones to bust out of this, defaulting on external debt, yanking the currency peg, embracing inflationary fiscal and monetary policy, and stimulating macroeconomic demand.

This brand of macroeconomic populism had a great six-year run (the red line) until the global financial crisis whose origins had nothing to do with Argentina and spurred a pretty good recovery from the crisis (the green line). The problem with this strategy isn’t that it didn’t work, it’s that it became less and less appropriate over time, eventually giving you the disappointing purple line and a downward spiral of collapse.

Going further back, one reason Argentine elites clung so tightly to the currency peg is that right up until it generated depression-scale conditions, that policy was working really well. Carlos Menem took over in 1989 during a period of hyperinflation, imposed macroeconomic normalization, privatized major companies, initiated deregulation initiatives, and successfully scored a huge influx of foreign investment that broke the back of inflation and led to a years-long economic boom.

All of which is to say that while it’s great that Milei has shifted Argentina from an inappropriate to an appropriate macroeconomic regime, that’s happened twice already during my lifetime, and both times, it’s created a very real economic boom that eventually petered out. What neither Menem nor the Kirchners was able to do was consistently change macroeconomic postures in correct ways, or generate sustained long-term productivity growth. That earlier leaders failed doesn’t mean that Milei will. But he hasn’t yet succeeded where his predecessors have failed.

Policies matter more than vibes

This article is about Argentina, but also on my mind, of course, is the United States of America.

In terms of vibes and political style, Milei and Trump are two peas in a pod.

In terms of actual policy, Milei took over a country that desperately needed fiscal austerity and is delivering it. Trump took over a country with a much milder need for fiscal austerity and is delivering a big increase in budget deficits. Trump is deploying trade policies that are reminiscent of Milei’s Peronist predecessors — not only high tariffs, but a kind of reveling in discretionary interventions in the economy because that maximizes his personal authority. I would not mind the aesthetics of Trumpism — the over-the-top rhetoric, the bombast, the cringe memes, the aspects of personality cult — if he were implementing smart, technocratically sound reforms. And there are maybe some areas, like clinical trials, where this is happening.

But we’re mostly getting attacks on free speech, attacks on scientific research, and attacks on the idea of independent civil society.

Meanwhile, I’m also concerned that a lot of people on the left have learned the virtues of a relentless political focus on affordability and the cost of living (as seen in Zohran Mamdani’s primary campaign) without actually learning any economics. If you try to deliver a rising living standard by imposing price controls on everything, you’re going to make the economic situation worse.

I’m not above the idea of pandering to the vote. But it’s a lot smarter to pander on questions of symbolism, rhetoric, and vibes than to adopt policies that have major technical failings. If people want complaints about greed or fulsome denunciations of the experts, then by all means, go ahead. I understand why a lot of the surface-level rhetoric around inclusionary zoning sounds appealing to people, for example, but the problem is the policy doesn’t make housing more affordable. You can probably keep the rhetoric, though, and just do better policy. I don’t think I can fully endorse the Milei move on dollarization, where you promise to do something incredibly stupid and then just don’t do it, but that’s a lot better than doing something stupid just because you promised it.

Because that’s ultimately a recipe for bad policy and political failure. The lesson of Argentina is that one of the richest countries in the world at the start of the 20th century lost that status thanks to generations of bad technical choices and has struggled to get itself back on track. This lesson deserves to be taken seriously.

For today's article, I have the good fortune of being an economist with family in Argentina. I have to say I disagree with several key points (as well as, ultimately, the takeaway for electoral strategy).

One thing you have to remember with developing countries like Argentina is that while the "macroeconomic management" does matter for growth to a certain extent, these countries' growth problems are mostly *microeconomic* and *political* in nature. The economy sputters because markets basically don't work at all, and the central bank/fiscal policy are way too captive to political considerations to keep *trend inflation* low.

Argentina is no exception. Over the past 20 years, a system had developed where there basically wasn't a single market-determined price in the entire economy. Successive Peronist governments (with a brief Macri interlude) had delivered a dizzying array of market controls, regulations, and subsidies, each meant to patch over an issue created by a previous government intervention. On the political side, one major reason the peg failed is that politicians, faced with incentives to over-spend before elections, never actually managed to get spending down to a sustainable level. Inappropriate "Neo-Keynesian management" is not the main reason why Argentina has failed to grow.

Milei's radicalism really can't be reduced to the dollarization proposal. The chainsaw/"Afuera!" represent a commitment to deal with the microeconomic problems. Indeed, Milei's government (advised by Sturzenegger) has already gone a long way in liberalizing Argentina's markets, with reforms to housing, labor markets, and trade policy. This more libertarian perspective is precisely what he was selling, and he was promising to do it in a much more extreme way than Bullrich. This was certainly not some sort of "centrist" approach to policy -- although economists see the merits of these reforms, many were worried about insufficient planning for the adjustment period.

Finally, we need to ask ourselves: if moderation is the key to winning elections... why didn't Bullrich win? I think you can't really escape the conclusion that Milei was just leagues ahead in terms of selling his agenda. Moreover, people were reasonably worried that Bullrich would talk a big game about "reasonable" reforms, which would then lead to something like the mild, temporary relief of the Macri administration rather than a true path forward. In a place like Argentina, sometimes you can't afford to be as risk-averse as a conventional candidate. Sometimes you just need to take a calculated risk and roll the dice!

Worth mentioning that Milei's party, La Libertad Avanza, has been a minority party in the National Congress and has had to form a coalition with Republican Proposal, the party of noted neoliberal Mauricio Macri, and a handful of independent parties to pass legislation. Dollarization was simply never on the table without an outright LLA majority.