The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic left a lot of obvious scars on the country — death, Long Covid cases, lost jobs, shuttered businesses, and the loss of valuable learning time in school.

But I think it’s also left significant psychic and political scars.

I spoke last year to a taqueria owner in Texas who told me she’d been a Democrat all her life but voted for Trump in 2020 because he and Greg Abbott were trying to keep her business open while Democrats wanted to shut it down. And having become unmoored from conventional Mexican-American Democratic Party loyalty, she discovered that there was a lot to like about GOP politics. She’s Catholic who favors legal restrictions on abortion, and a small business owner who’s skeptical of minimum wage increases. Which is to say she’s part of a larger trend of conservative Hispanics discovering that they want to vote for the more conservative party — that sounds banal, but the pandemic was such a shocking and disruptive moment that it caused people to rethink a lot of things.

Conversely, for many others, the definitive moments of pandemic policy were things like Donald Trump promising the virus would vanish by spring, the infamous “cubic model” chart, the boast that he’d cured the virus with Regeneron, the endless rounds of hype about hydroxychloroquine, and various other forms of nonsense peddled by the political right.

And even today, almost nothing gets people fighting in the Slow Boring comments like disputes over what really happened during the pandemic — not so much about whether lockdown forever would have been a good idea (nobody thinks that) or whether Trump was correct to promise that the virus would simply vanish without harming anyone (he clearly wasn’t), but about the actual balance of wrongness. People tend to engage in a lot of flattering misremembering about their own views and the views of their ideological fellow travelers, with Covid doves taking real facts about the situation from late 2021 and retrocasting them to summer 2020 and hawks declining to specify exactly what they wish would have been different on a policy level.

My goal in this piece is to recount the evolution of my own thinking in an honest way, reflecting on what I think I got right and on my current retroactive view of things, but also owning up to the fact that, like most people, I was making assessments in real-time with imperfect information and minimal experience. In other words, what I got wrong.

Early Covid fatalism

I never covered public health or infectious disease issues professionally, but I’ve had a kind of hobbyist interest in this stuff since childhood.

I loved Laurie Garrett’s 1994 book “The Coming Plague,” and I was a big fan of both Jared Diamond’s “Guns, Germs, and Steel” and William H. McNeill’s macrohistory “Plagues and Peoples.” I’ve read “The Stand” several times and watched multiple film adaptations. I joke about “Dune” a lot, but Frank Herbert also wrote a pandemic apocalypse book “The White Plague” that I was a huge fan of in high school. So when a novel virus arose in Wuhan, China, the story was very much on my personal radar.

As the events of February 2020 played out, it became clear to me that the pandemic was going to go global (the correct call) and my view was that basically nothing would be done to halt it (incorrect).

I thought the pandemic would play out essentially as it did in March of 2020. The virus was spreading rapidly in the tri-state area and as governors there imposed heavy restrictions, many of the region’s more skeptical residents departed for Florida. Ron DeSantis responded by trying to impose mandatory quarantines to prevent northern transplants from spreading the virus locally. I thought every jurisdiction on earth would:

Attempt border controls only once the virus had already entered on a small scale

Impose internal controls only once the health care system was overwhelmed

By imposing internal controls, encourage people to flee, thereby restarting this cycle in a new location

The result would be a huge, intense pandemic in which many, many people were going to die. My role, as a husband and father and pandemic-book-enjoyer, was to prepare my household for a situation in which chaos would sweep over Washington D.C., with hospitals absolutely jammed and elderly patients triaged out of care, left to die in the hallways or in their homes. My thought was that during the peak of the crisis, it might be important to shut ourselves up at home for a while, so I went to Costco to stockpile stuff — dried pasta, jars of Rao’s, frozen vegetables, canned beans, over the counter medicine, first-aid supplies (including surgical masks), bottles of water and purification tablets, batteries, and everything else we’d need to ride out a disaster.

But this was prepper stuff, not personal Covid caution.

In the first week of March, I took a brief work trip to New York City to attend a Vox Media revenue conference and meet with my editors on “One Billion Americans.” I brought hand sanitizer and wipes with me on the trip, but that was the extent of the precautions I took. A couple of days later, we hosted a fifth birthday party for our son — again, with an unusual degree of vigilance about hand-washing and basic hygiene, but no thought of shutting down society. Meanwhile, I was waiting to ride out an inevitable crisis because I didn’t expect any policy response at all.

Curve-flattening and suppression

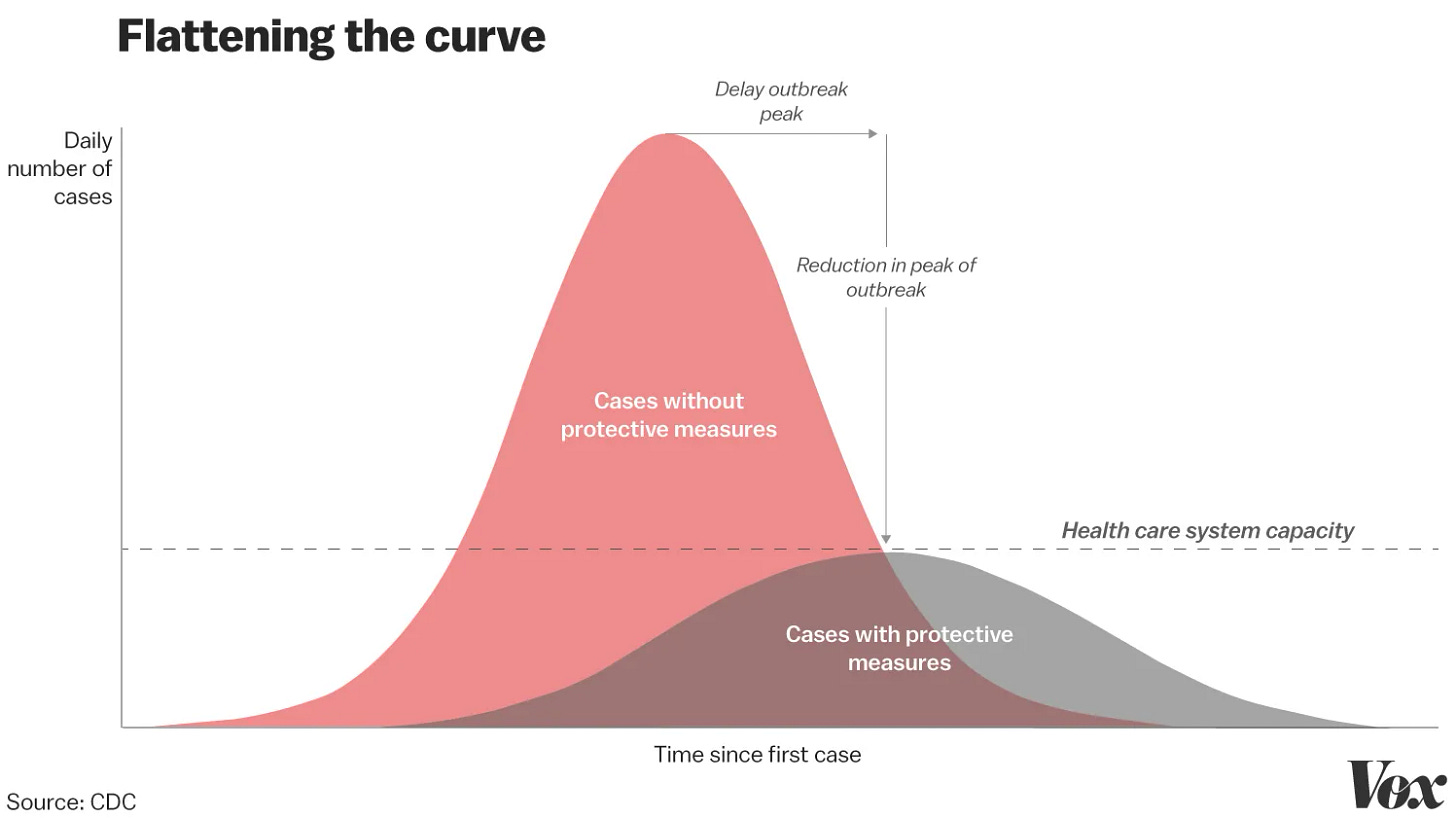

It was soon after this that I learned about the idea of flattening the curve.

The idea — which I think is still underrated — is essentially harm reduction for pandemics. The point is that while there probably isn’t a cost-effective way to prevent a new disease from coming to your city, you can avoid the crisis situation I was worried about and make sure that everyone who’s sick gets treated.

The way you achieve this, to quote a March 10 Vox graphic, is by trying to impose enough restrictions on activity to slow the spread of the virus and distribute the caseload over time. This ensures that everyone who needs treatment gets treatment and prevents the infection fatality rate from soaring.

This struck me as convincing, and of course that’s the difference between worrying about something as a human individual and worrying about it from a policy viewpoint. I’d thought a lot about pandemics over the years but never really considered them as a subject for coordinated policy.

My worst call of the year, though, came about six weeks after that piece ran when I got a bad case of Taiwan envy and called for the United States to try to emulate Asian-style total suppression of the virus.

I think that if you read the specific arguments of that piece, it sort of makes sense. I was saying, basically, that a super-intense total suppression lockdown could be relatively brief and then allow more freedom (as well as more lives saved) than a prolonged period of curve-flattening. But it was totally detached from political reality. Not only was the consensus in favor of pandemic-halting action already breaking down in conservative areas, but progressives would never in a million years license things like cops kicking in doors to bust up illegal house parties.

I pretty soon started writing more pragmatic pieces about how we should reopen parks and encourage people to do stuff outside (April 30) and make reopening schools in the fall of 2020 a top priority in our social and economic planning (May 28). But what I never did while I was still at Vox was write clearly about how, in practice, that all meant giving up on suppression and returning to curve-flattening as a standard. Instead, as I think you’ll see in the May episodes of The Weeds that I did with Ezra Klein, we were both kind of fascinated with highly technocratic ideas like Paul Romer’s mass testing plan. Re-listening to that episode, I think Ezra did a much better job than I did of articulating how unlikely it was that anything like this would ever be done given the actual realities of the American situation, while I just really wanted to believe in the power of a good idea.

Vaccine time

Once vaccines were approved in November 2020, I think I consistently had the correct high-level view:

It made sense to be very cautious in your personal behavior until you could get the vaccine.

It made sense to have a simple prioritization scheme for scarce doses — give it to old people — so as to maximize benefits.

Vaccination reduced society-level vulnerability so much that it made sense to lift all restrictions once the shots were widely available.

In curve-flattening terms, the point was that a highly vaccinated population was just extremely unlikely to develop crisis-level case volumes. The benefits of non-pharmaceutical interventions became much lower, while the costs remained high.

On the details, though, this was also a time when I took a number of wrong positions in public.

I was very frustrated, intellectually and emotionally, with school closures. I argued against closing schools before the vaccines were available, but had lost that argument internally to the politics of blue states. I wanted vaccination to be the game-changer that ended NPIs, so I expressed erroneous overconfidence about the vaccines’ ability to block transmission. And because I overestimated vaccines’ ability to block transmission, I overestimated the case on the merits for mandatory and quasi-mandatory means to promote vaccination. A lot of conservatives see arguments for vaccine mandates as an example of Covid hawk extremism, but I think a lot of us embraced them as an alternative to Covid hawk extremism.

But factually, though the vaccines are very useful, their impact on transmission (especially post-Delta) was limited. Mandates turned vaccination into a wedge issue that advantaged Republicans rather than Democrats. And the Biden administration spent months continuing to support increasingly ineffective mask mandates, only truly seizing the vaxxed and relaxed mantle when forced to do so by federal courts.

This was a sort of interesting period in American political life. Biden dragged his feet too much on the masks; DeSantis turned into a soft anti-vaxxer. But I think a lot of non-famous governors from both parties converged fairly quickly on the correct policy, and eventually so did Biden.

We should have followed the plan

I, personally, struggled to make correct decisions about Covid because I was responding to a new and unfamiliar situation with imperfect information.

But looking back on it, I think the best course of action for the United States was the one embedded in that March 10 Vox article about curve-flattening. I really think it’s worth everyone’s time to revisit commentary from that early March 2020 era, because it’s strikingly different from what eventually emerged out of a very polarized debate. There’s no dismissal or denialism of the severity of the virus in the piece, none of Trump’s false assurances and none of the biting mockery of people for being concerned about it. But relative to what would later become the Covid hawk position, it’s incredibly moderate:

“Even if you don’t reduce total cases, slowing down the rate of an epidemic can be critical,” wrote Carl Bergstrom, a biologist at the University of Washington in a Twitter thread praising the graphic, which was first created by the CDC, adapted by consultant Drew Harris, and popularized by the Economist. The chart has since gone viral with the help of the hashtag #FlattenTheCurve.

And later:

The CDC advises that people over age 60 and people with chronic medical conditions — the two groups considered most vulnerable to severe pneumonia from Covid-19 — to “avoid crowds as much as possible.”

“If more of us do that, we will slow the spread of the disease,” Emily Landon, an infectious disease specialist and hospital epidemiologist at the University of Chicago Medicine, told Vox. “That means my mom and your mom will have a hospital bed if they need it.”

And last:

“From a US standpoint, you want to prevent any place from becoming the next Wuhan,” said Tom Frieden, who led the CDC under President Barack Obama. “What that means is even if we’re not able to prevent widespread transmission, we want to prevent explosive transmission and anything that overwhelms the health care system.”

These are serious, sober-minded public health professionals outlining a fairly dovish stance on Covid. Not “let ’er rip” by any means, but a policy approach with fairly limited ambition. I think this approach would support things like the NBA bubble season and remote work, and would generally validate cautious behavior as virtuous. But most businesses would at least be allowed to continue operating, and critical social services like schools and the court system could have kept functioning, except when cases were threatening to overwhelm hospitals.

And because these were serious, sober-minded public health professionals, their harm reduction line was not infected by conspiracies, dismissiveness about the virus, the impulse to tout fake cures, or other hallmarks of Trump’s response in the summer of 2020. Importantly, the reason public health professionals converged on this curve-flattening idea in early March 2020 is that it’s what the pandemic response playbook written in the period between 9/11 and the swine flu scare of 2009 said we should do. Most of us did not pay a lot of attention to that pandemic planning work, but it resulted in some pretty good ideas and we should have stuck with them. I’m not 100% sure why we didn’t. But during Trump’s “15 Days to Slow the Spread,” two crucial things happened — Trump decided he didn’t actually care about slowing the spread, and the public health community flipped to something more like a Covid Zero mindset. I still don’t really know why either of those things happened.

I, personally, was a little too impressed with Taiwan. But why didn’t the public health professionals who originated “flatten the curve” (presumably because they had thought this through more clearly than I had) not stick with it? Rather than mandates, the reasonable approach would have been to combine curve-flattening with CDC advice that reflected our emerging understanding of the scientific facts: Outside is better than inside, windows open are better than windows closed, HEPA filters help, good masks help, physical fitness helps, age is the main predictor of severity, etc.

My dream is that someday, someone will do really rigorous reporting on this, which I haven’t yet seen. But my best broad guess is that two factors drove the dysfunctional response. One is that Trump is an undisciplined guy whose go-to political move is driving polarization rather than consensus. The other is that social media totally wrecked America’s epistemic institutions. Once “Trump should take this more seriously” (which was true) became a narrative on Twitter, the situation quickly devolved into one in which the best lacked all conviction and the worst were full of passionate intensity. In the media, the number one constituency for clicking on and sharing Covid-related articles was the most neurotic super-doves, and the number two was nut-job conspiracy theorists.

That kind of dual-humped debate was antithetical to the harm reduction goal of articulating a sustainable strategy.

Really enjoyed this article. I do think it misses a key part of the story which is the seeming success of South East Asian, Australiasia and even European countries in supressing the virus compared to Britain and America. That really fed the narrative that the two English-speaking countries led by the hated populists had taken the virus lightly, and if we just had the common sense/determination to impose a proper lockdown then all would be well. This gets discredited as the virus spreads around Europe to the point that the UK is a middling rather than unusually bad performer, China proves to have been lying about its covid success, and other countries with the harshest lockdowns struggle to come out of them. And of course US/UK lead the world in developing and distributing vaccines. But I think in 2020 there was a real crisis of confidence in American and British science/medical communities that they had gotten this big call wrong

I had the very interesting experience of going into the pandemic as a public health person, but only on the undergraduate education side, and as an expert on pandemics specifically, but from a historical standpoint--that was my original academic training, and I had opened an exhibit on pandemics at Philadelphia's Mutter Museum at the end of 2019, literally a couple months before the actual pandemic (it was tied with a big Flu 1918 retrospective). So I knew a lot but had nothing to do with actual policy in any respect; I was just an observer. I had a lot of time to watch and think about what was happening. I did a little bit of writing about it on my blog that I think held up pretty well (if you're interested, website in my profile).

But one of the things I did both predict and watch happen in real time was a kind of breakdown amongst public health people who had actual or theoretical policy influence. Basically, you had a lot of people who I think in their heart of hearts believed that their expertise would matter more than it did. A lot of those folks kept thinking or even saying something along the lines of, "When it gets bad enough, people will realize that they should pay more attention to me / us." If you go back and re-read about Florida's reopening, for instance, you will find some great quotes along those lines. And a lot of those folks, or at least the smart ones, had a more or less accurate view of how bad it would be. I think we forget just how bad the numbers were: a lot of people died or were long-term disabled. Like, a lot a lot.

Since I had studied the history of pandemics, I knew that this would not happen. That's just not how it works. Public health people in Philadelphia got ignored while they were burying the dead in trench graves with steam shovels. Humans get comfortable with very surprising levels of suffering at astonishing speed, in a this-is-fine-dog-meme kind of way. The moment was never going to come for my colleagues where everyone was like, "This is your moment! Lead us! We agree with you about all kinds of things that we didn't agree with you about earlier!"

And I think a kind of sincere bitterness or disappointment over that drove at least some of the counterintuitive hardcore Covid doomerism amongst some of the public health community, because those folks kept expecting (and, because they were human, kind of secretly wanting) their moment to come, and it was never going to come. At least, that was one of my impressions.