Trump turned off critical food assistance for millions

SNAP is good; killing it is bad.

Today’s post is about SNAP and the harm Republicans are inflicting by refusing to fund it. If you’re interested in helping Americans who aren’t receiving their benefits this month, our friends at GiveDirectly are raising money to send cash to those impacted. Please consider helping if you can.

It’s hard to cover ongoing, dynamic events like the government shutdown on a newsletter publication schedule, and I also trust that people are not relying on Slow Boring as their only news source. I assume that you, like me, are reading stories every day about the back-and-forth between congressional leaders.

But I do want to take some time today to talk about the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps), because over the weekend the Trump administration essentially decided to turn the program off.

During an appropriations lapse, most of the government’s discretionary programs shut down, but programs like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid that are funded on an ongoing basis rather than through annual appropriations continue.

SNAP is one such program, which is why it wasn’t impacted when appropriations originally lapsed. However, administering the program requires a modest amount of spending over and above the expenditure on the benefits, and the appropriations for that administration ran out at the end of October.

The White House could — but chose not to — tap an emergency fund that exists to keep the program running.

There’s going to be litigation as to whether Trump truly has discretion here or is just breaking the law. But SNAP benefits won’t be paid this month unless judges intervene. And while the non-payment is in a sense because of the shutdown, it was not a forced move. The White House believes that cutting off SNAP payments will increase pressure on Democrats to cave, because they believe that Democrats care a lot about the safety net and the lives of poor people.

An interesting quirk of American politics is that lower-income states tend to be more conservative so, in a sense, the economic hit of sharply curtailed low-end consumption falls harder on red America.

For a very long time, though, this was a bit of a fallacy of composition. Democrats did better in richer places but worse with richer people. In 2012, for example, even though Barack Obama lost the white working class pretty badly, he actually won a majority of support from poor white people. And, of course, he dominated with low-income Black and Latino voters.

In 2016, though, poor whites swung hard to Trump. Then in 2020, Trump gained a lot of ground with Hispanics; in 2024, he gained even more. Across all three cycles, meanwhile, he made small-but-real gains with African-American voters. There is no publicly available polling on how SNAP beneficiaries specifically voted, but my understanding from people who’ve tried to look at it is that he did historically well for a Republican among public assistance beneficiaries.

So the politics of firing this gun may not play out exactly how Republicans hope.

That said, what I actually want to talk about today is the substance of SNAP. It’s hard, journalistically, to cover static facts about the world, but SNAP is a big important program that makes a real difference in people’s lives. Trump shutting it down is a good time to talk about that, and also a good time to mention GiveDirectly’s program where you can give money to Americans directly impacted by this situation.

SNAP is a really big deal

SNAP is a large program, but most people don’t think about it very much, to the extent that one of the most common reactions I saw to news of looming cuts was incredulity that nearly 12 percent of the population could really be receiving food assistance benefits. And a lot of that spiraled into conspiratorial thinking about massive underestimates of the immigrant population or benefits fraud.

But the poverty rate in the United States is either 10.6 or 12.9 percent, depending on which measure you use, so the scale of food assistance shouldn’t be surprising. And the demographics of SNAP are similar to other American anti-poverty programs: the biggest groups of enrollees are children, the elderly, and the disabled, and the program skews significantly toward single mothers and their kids rather than two-parent households.

In general, I think people tend to underrate both the fact that the United States is a very rich country — not just in the sense of billionaires or the top 1 percent, but that our median living standards are much higher than in Europe or Asia — and also that it’s a really hard place to be poor. The prosperity of the country tends to make things a little expensive here, because you’re either hiring the labor of residents of a rich country or bidding against the residents of a rich country for scarce goods.

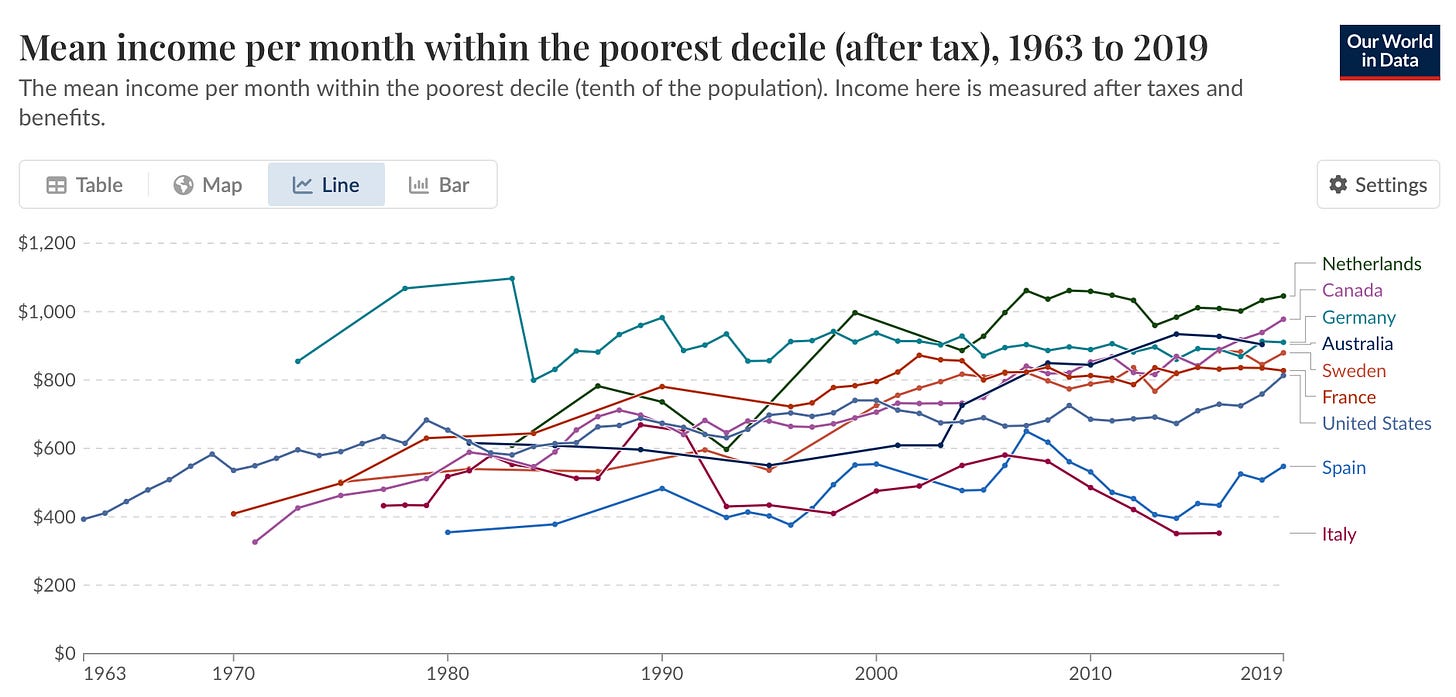

If you look at living standards in the poorest 10 percent of the population, the bottom decile of Americans is doing worse than the bottom decile of Canadians or Australians or residents of northern Europe.

Reasonable people can disagree as to what to make of that, but it’s one of the most important structural facts of American life.

Somewhat flexible help for the poor

On average, SNAP recipients receive $187 per month, but poorer families get more and less-poor ones get less. It’s not a particularly generous program. But relative to the rest of the American safety net, it’s a flexible program in that it takes a fairly expansive view of what counts as groceries. When I was a kid and recipients had to bring actual food stamps to the grocery store to get their benefits, their use of the program was quite obvious to anyone behind them in the checkout line. But in the modern world, benefits are administered via an Electronic Benefits Transfer card that looks and functions like a debit card or a credit card, so it’s easy to miss — perhaps one reason people seemed to be surprised by the scope of the program.

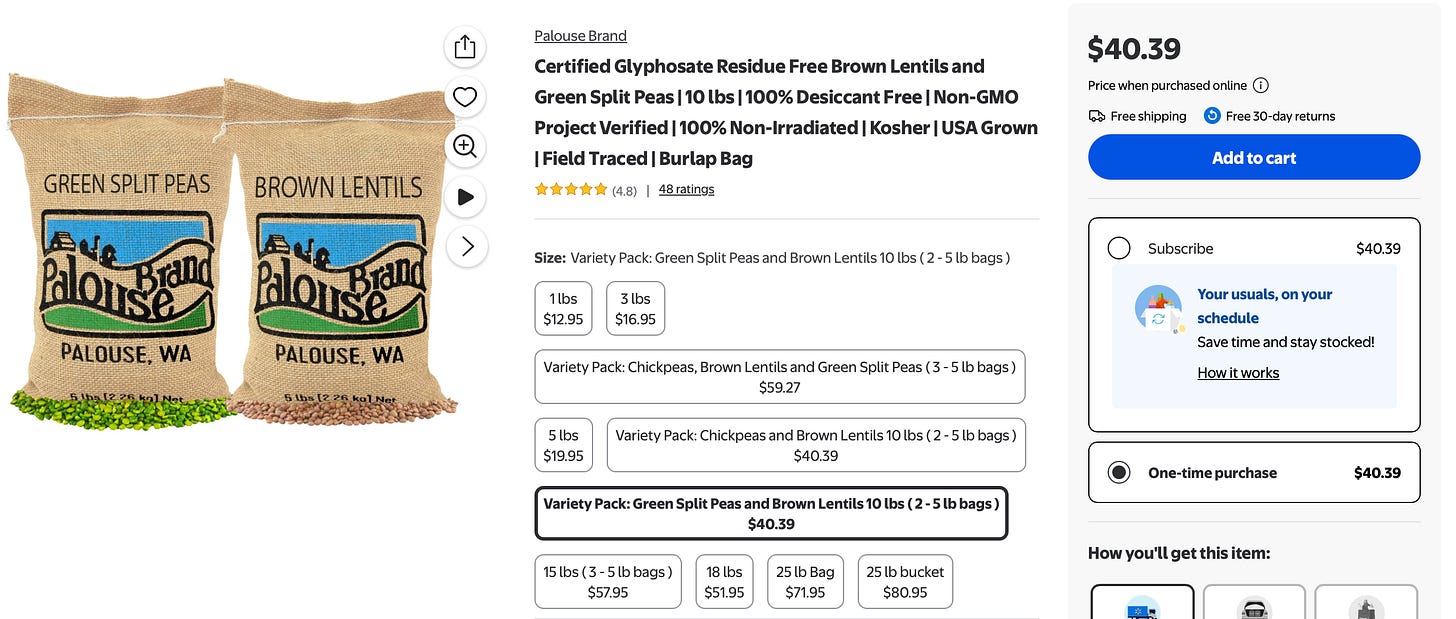

The merits of SNAP as a relatively user-friendly program also leave it somewhat vulnerable. We could make giant sacks of dried legumes available to needy families to avert starvation rather than subsidizing the purchase of a wide range of groceries of their choice at normal stores, and that would more closely fit some people’s sense of what “nutrition assistance” should look like.

The flip side, of course, is that flexible assistance is much better at meeting people’s subjective needs than handing out giant sacks of lentils.

Because I tend to like things to be conceptually tidy, my personal preference would be to have a cash assistance program for the poor and an in-kind nutrition assistance program. The nutrition program of my dreams would be much more paternalistic than SNAP and geared specifically toward getting people healthy food. The cash program would be cash that people could spend on food they like or housing or socks or diapers or whatever else. But that is not the world we live in, and SNAP plays a dual role as an actual nutrition program and as general income support.

An interesting fact about SNAP, though, is that, as Justine Hastings and Jesse Shapiro show, it really does increase food consumption more than an abstract economic model might predict.

You can look at households that receive SNAP but have household expenditures on SNAP-eligible items that are higher than their SNAP benefits. When a family like that gets more SNAP, they in some sense “should” keep buying the exact same amount of food and simply spend less cash on food and more on something else. But that’s not the case. Instead, every new dollar of SNAP generates about 50 to 60 cents of additional spending on SNAP-eligible items. So not only do the program rules matter, they in some sense matter more than they ought to. This is part of a larger literature on mental accounting that finds, for example, people bought more premium gasoline during the Great Recession because gas prices fell.

The SNAP literature itself, meanwhile, mostly shows good effects.

It’s good when people have food

An interesting paper from Martha Bailey, Hilary Hoynes, Maya Rossin-Slater, and Reed Walker on the impact of SNAP published in April of 2020 provides important context for the debate over universal basic income.

The authors take advantage of the fact that the food stamp program rolled out on a county-by-county basis over a period of 14 years (1961 to 1975). They combine that with large-scale Census Bureau and Social Security Administration data to track 43 million people over time and look at the long-range impacts of early exposure to these benefits.

What they find:

Children with access to greater economic resources before age five experience an increase of 6 percent of a standard deviation in their adult human capital, 3 percent of a standard deviation in their adult economic self-sufficiency, 8 percent of a standard deviation in the quality of their adult neighborhoods, 0.4 percentage-point increase in longevity, and a 0.5 percentage-point decrease in likelihood of being incarcerated.

Those aren’t huge impacts1, but they’re large relative to SNAP’s cost of a bit over $2,000 per year.

I think it was reasonable to look at those results and suggest that giving even more financial assistance to low-income families would lead to even bigger results. Unfortunately, it does not seem that this is as obviously true as one might hope. One possible takeaway from the disappointing results from the cash experiments is that this was wrong and that diminishing marginal returns set in pretty fast. But in that case, the upshot would be less that giving poor families money doesn’t improve long-term outcomes for kids, so much as that small amounts of additional money don’t help with long-term outcomes when support already exists.

The Bailey and coauthors study is my favorite and I think has the strongest research design, but there are various other studies showing positive impacts of SNAP.

A noteworthy one looks at variation in timing. SNAP benefits pay out once a month, so poor families are normally more flush at the beginning of the SNAP cycle and more stretched at the end. The paper shows that low-income students who take the SAT or ACT in the final two weeks of the cycle get lower scores and have lower odds of attending a four-year college. Again, in part that’s a story about the quirks of human decision-making. Theoretically, poor families could and should smooth their consumption. But in practice they don’t, and kids go hungry.

The safety net matters

Economic growth matters more than redistribution to the long-term prosperity of humanity, and I’m always happy to urge any and all to adopt pro-growth policies. But I don’t see that as a major partisan dividing line.

What I do see as a big dividing line is the one that separates a right that is obsessed with minimizing the tax burden on the wealthy by any means necessary from a left that believes in crafting institutions that guarantee a rising tide lifts all boats. I think that’s better in a utilitarian sense and also provides a solid foundation for the existence of a stable but economically dynamic democratic society over the long run.

To me, personally, these questions around defending and improving a basic social-safety net are at the core of politics. But these topics have really fallen into abeyance over the past 10 years.

There’s a style of left politics that is obsessed with the wealth of the richest people, that insists a politics that prioritizes making the tax code more progressive and expanding the safety net for the poor isn’t worth the effort. This brand of politics insists that middle-class Americans are living in some kind of economic hellscape, and it’s only real economic populism if you’re focused on crushing the power of the rich rather than lifting up the poor.

That does not appeal to me, any more than a right-wing politics of cultivating indifference to human suffering, and I think this shift has been pretty unfortunate. I wish we could spend more time talking about things like SNAP and Section 8 and Medicaid and how to improve these programs.

But here we are, in a government shutdown that is fundamentally about Trump’s thirst for personal aggrandizement. And as part of that, he’s decided to just turn off a crucial program to support the well-being of low-income families while plowing ahead with the construction of a ballroom and blowing up boats in international waters. It’s bad!

And just a reminder that if you also think it’s bad and would like to do something in the short term to help the people who are suffering the most from the shutdown, you can support GiveDirectly’s efforts here.

Reporting things in terms of standard deviations is annoying, but if you look at the charts in the paper this amounts to saying that they get more education and are less likely to be in poverty by small but statistically significant amounts.

Matt writes: "I assume that you, like me, are reading stories every day about the back-and-forth between congressional leaders."

That sounds awful, and I hope very few of my fellow readers are doing this.

But to each his own, I guess.

To me guarantee of sufficient food is the kind of moral imperative that a society as wealthy as ours can't ignore. It also demonstrates the dangerous game the Republicans have played by empowering someone so fundamentally callous. Trump isn't a risk free decision, even in red America. I'd like to think some of the grumbling we've heard about it, even on the right, is maybe a sign that deep down there's some understanding of just how bad this, and the cut of the ACA subsidies is, not just from a policy standpoint but for the national character. Not that I'm holding my breath for any kind of reassessment of priorities on their part anytime soon, but it's telling that you don't hear a lot of standing up for it on the merits.

Anyway Matt's aside on just how wealthy the US makes me want to re-share part of my comment yesterday on the open/question thread, which was: "The north star [of left wing politics] is probably still something like ensuring fairness and that the wealth of our society is distributed such that everyone has a reasonable standard of living. But it also has to deal with the fact that we probably aren't ever going back to a mass employment industrial economy, that technology is increasingly going to result in fewer low skill (and at some point high skill as well) living wage jobs, and that the organized labor movement has run its course as a force for progress."

I think SNAP is one of the better operationalized programs to that end, and it's worth defending as such, even as other ideas probably need to fall by the wayside. It's flexible, portable, and has a universal kick-in which should be the model for as much as possible.