The myth of the "great resignation"

It's a hiring boom

The American labor market is being haunted by the specter of a “Great Resignation.” I think this is, in crucial respects, fake.

The rate at which people are quitting their jobs really is unusually high, and policymakers ought to take it into consideration when thinking about the labor market. But this high quits rate is often framed as a kind of cosmic revaluation — a Bloomberg headline suggests “workers are opting out” while Yahoo reports that “Americans are rethinking their work expectations” — in a way that’s not supported by the data.

The quits rate is unusually high, but the hires rate is also unusually high, and the ratio of hires to quits is very normal.

In other words, people aren’t dropping out of the labor force or embracing the ideology of “antiwork.” They are quitting their jobs in the sense that back when I was 25, I quit The American Prospect to go work at The Atlantic — in other words, I got a better job.

It’s also worth saying that while the current quits rate is at a historic high, our history of this metric only goes back to December 2000. We know it varies with the state of the labor market, but we don’t really know what kind of quits rate we’d expect in a boom because the quits data doesn’t go back to any labor market boom years. And that’s what we are seeing here: with a very strong demand for hiring, lots of people are taking the opportunity to switch jobs. This ought to reorient our policy thinking — efficiency matters more and “creating jobs” matters much less than it did in the Bush and Obama years — but it’s not some kind of mass walk-off.

The great hiring surge

The United States right now is experiencing an extremely elevated rate of hiring. Businesses have spent the past 18 months reopening on a rolling basis as legal restrictions on activities have rolled off and consumer demand has rolled on. At the same time, the federal government has pumped dollars into people’s pockets, generating a lot of spending and also a lot of hiring to meet the demand that the spending creates.

But new hires don’t materialize out of the ether. You need to hire them from somewhere.

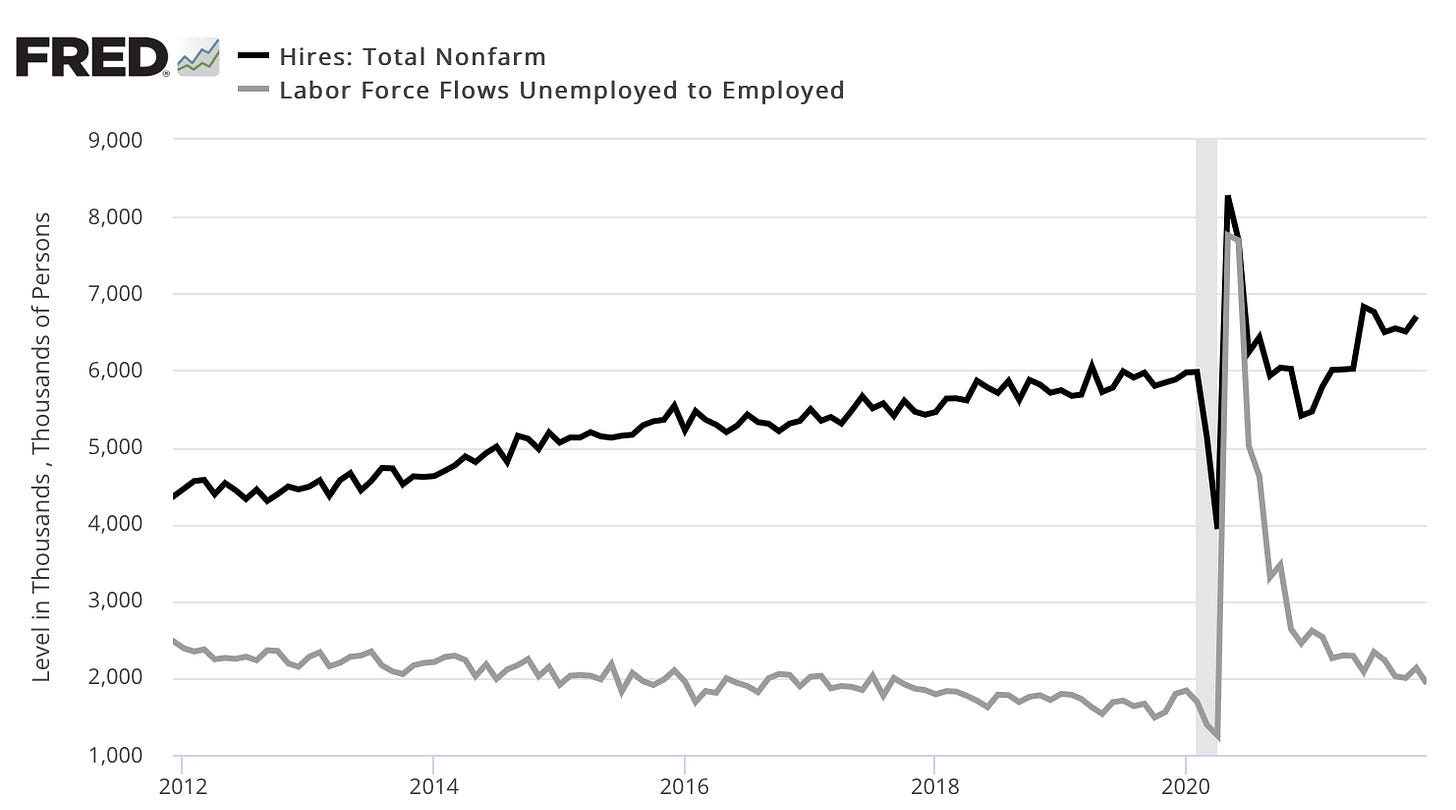

You can, of course, hire currently unemployed people. But except in the special case of recalling workers from temporary lockdown-related furloughs, the volume of gross hiring always greatly exceeds the number of unemployed people who get jobs.

And going from “not in the labor force” and supposedly not looking for a job to employment is actually much more common than going from unemployment to employment.

But even when you add these two up, there is significantly more total hiring happening than non-working people getting a job.

That’s because when a company hires someone, they are usually hiring someone who already has a job, oftentimes a pretty similar job. That’s how the economy has always worked. These are called “quits” in the Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers, but that doesn’t necessarily mean someone got so fed up that they quit their job and slammed the door on the way out. That is a quit in the BLS numbers, but so is thanking your manager for a few good years and a lot of lessons learned, letting her know you got an attractive offer elsewhere, then shaking hands and having some cake in the break room.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.