The case against "creating jobs"

With full-ish employment, efficiency should be back in style

The infrastructure legislation that Joe Biden signed earlier this fall is formally known as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and it descends in some sense from the American Jobs Plan that the White House rolled out at the beginning of the year.

Emphasis on jobs reflects the fact that government spending money on infrastructure projects entails hiring people to do work. But it’s not actually true that “in order to create jobs” is the reason to build infrastructure. And this is not unique to the infrastructure issue. Across a whole range of issues, emphasizing the job creation aspect of public expenditures is a staple of progressive rhetoric — in part just because it sounds good to people, and I can’t begrudge politicians for doing politics. But in part, it’s a reaction to a very prolonged labor market slump that we had in the 21st century which made “creating jobs” seem like priority number one at all times.

In the real world, though, this is not why we want to promote clean energy, expand health and dental coverage, or bolster the availability of early childhood education. Those things are all virtuous and important in and of themselves. The job creation sales pitch was a reaction to 20 years of catastrophic macroeconomic mismanagement. But you want to power people’s homes, reduce pollution, and clean their teeth. And now that we have an economy where it’s much easier to find a job than it was at any time during the 20 pre-pandemic years, it’s time to adjust our thinking.

Back in September, Rachel Ramirez and Ella Nilsen wrote a piece for CNN headlined “Democrats say a Civilian Climate Corps will create jobs. Here's how it could work.” The model here, obviously, is FDR’s Civilian Conservation Corps, which among other things provided much-needed work relief for an economy ravaged by the Great Depression. The job-creating aspect of the CCC wasn’t an incidental piece of framing — Roosevelt was desperately trying to put people back to work during a time when jobs were scarce.

Today, though, jobs are not scarce.

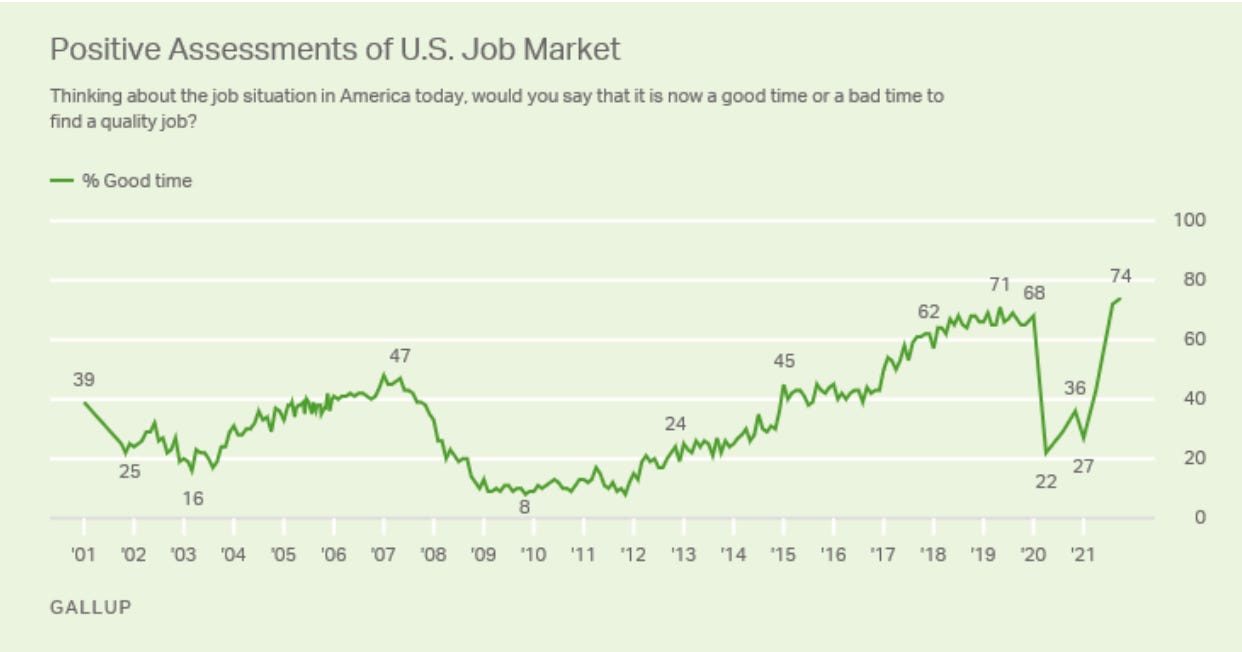

It’s not that everything is perfect in America. Far from it. But at the moment we have many more cases of employers struggling to fill open positions because the labor force has shrunk than we do of people who can’t find work. Indeed, even as the economic mood has turned sour thanks to inflation, people say this is the best time throughout the 21st century to find a job.

I’m not sure how much this change of circumstance will alter the politics of selling ideas as job-creating. But it ought to at least somewhat alter the substance of what elected officials try to do. Unfortunately, people tend to fight the last war, so while Obama-era Democrats had a somewhat perverse obsession with “bending the cost curve” on health care even while tons of labor went idle in the United States, today’s politicians are not thinking as clearly as they should about what kinds of new spending make the most sense in an era of full employment.

The long slump

Everyone knows the Great Recession was bad. But what I think is underappreciated is that even though the recession starting around when George W. Bush took office wasn’t especially severe, it was weirdly long-lasting and the recovery was very slow.

The employment-to-population ratio for prime age workers kept falling literally for years after the official end of the recession. And by the time a new and worse recession happened, it still had not recovered.

In pure “shape of the curve” terms, the bounce-back that started in 2010 was actually better, but this time the economy was in a really deep hole. By Obama’s second term, people were convincing themselves that it was impossible to get back to where we were in 1999. But then the recovery just kept on continuing for Obama’s last two years and Trump’s first three, and I now think it’s obvious that had the pandemic not intervened, we would have gotten there.

For a long time, policymakers were much too slow to react to this slump.

That manifested, in part, in a lot of worrying about the budget deficit even though interest rates were super low and tons of people were out of work. If you looked past the veil of money, this never made a lot of sense. Obama’s OMB Director Peter Orszag was obsessed with wasteful health care spending. As a guy who likes things to be orderly and rational, I basically agree with all the high-level points he was making about this. But in practical terms, it’s hard to understand what the fire was. The United States was not suffering from any shortages of labor or capital goods that could be attributed to bloat in the health care sector. So even the best-executed plans to make it work more efficiently weren’t going to accomplish very much.

But people in progressive nonprofit land started to get seriously Keynes-pilled during this period, so Democrats’ post-Obama policy agenda was heavily structured around the idea of mobilizing idle workers to do things.

New Deals, green and otherwise

The most obvious version of this framing was the Green New Deal, which in a very literal sense positioned itself as a solution not just to climate change but to mass unemployment. The Sunrise Movement said its ideas would “create millions of jobs,” and the GND House resolution, similarly, has a pledge “to create millions of good, high-wage jobs in the United States.”

In Bernie Sanders’ version of this he posited 20 million new jobs, while Elizabeth Warren had “10.6 million green jobs.”

Sanders got the higher figure, I think, because he was counting child care jobs as green jobs, which other Democrats didn’t do. But if you look at the child care provisions of Build Back Better, it’s clear that Democrats are aiming to expand the child care workforce.

This all goes to show that New Deal-ism was not limited to the climate topic. And critically, it’s not particularly limited to the left wing of the party, even though the left’s programs and jobs numbers are bigger. Back in March, Biden was talking about “the largest jobs investment since World War II,” referring to his infrastructure plans but also his proposal to expand home care subsidies for the elderly and disabled.

And these were all themes that carried over from Biden’s campaign. The original use of the Build Back Better slogan came with a release that started like this: “After six months in the pandemic, we are less than halfway back to where we were — with 11.5 Million Americans not yet getting their jobs back.”

Today, workers are scarcer than jobs

But while it’s true that employment has not yet fully recovered, it really does not seem to be the case today that the proximate issue is a lack of demand for labor.

You can say that the jobs available don’t pay enough or they’re not good enough or criticize them however you like. But it’s just obvious walking around and living your life that tons of places are hiring. Just the past couple of days, I’ve seen “help wanted” signs at Target, Whole Foods, Sweetgreen, Starbucks, and McDonald’s along with God knows how many independent restaurants. And D.C. doesn’t even have a particularly hot job market since we’re heavily impacted by remote work hurting the foodservice and retail sectors of our downtown office district.

Now, none of this is to say that the missing workers from the pre-pandemic era will never return. The economy does keep adding jobs at a decent clip, and I think things will pick up even more when (if?) the public health situation improves.

It’s just to say that we are not currently constrained by an objective lack of employers trying to hire workers. And even though many of the jobs offered are fairly low-wage, that’s still very different from what we saw in 2002-05 or 2007-14. Back then, lots of people desperate for work couldn’t find any — and in particular, people who didn’t have a work history or who had a red flag somewhere on their record were locked out of the opportunity. That’s not the case today, which is good.

But it also means that if you really did want to hire millions of people to go work in new child care centers or zero-carbon energy projects, they’d probably have to come from somewhere.

Progressives’ implicit theory of social transformation

If you look at the specifics of the House’s version of Build Back Better, I honestly don’t think there’s a major problem.

But if you think about a more expansive version of progressive ambitions like the original $3.5 trillion proposal or Bernie Sanders’ $6 trillion one, then I think it starts to emerge. Progressives believe that Medicare beneficiaries are currently underinsured and should be receiving dental, hearing, and vision coverage so that they can consume more health care services. And of course, they also believe that non-recipients of Medicare are even more underinsured and should receive additional coverage of their own so that that can consume more health care services, too. They believe college is too expensive, and people should be consuming more higher education services. And they also want us to consume more preschool and child care services. Then there’s the home care idea for the elderly and disabled that we have too many people receiving care in institutionalized settings and more should be getting care at home in a more customer-friendly but less labor-efficient manner.

Well, for that to happen, you’d need a lot more people working in the health care and education sectors, and the question is … who?

A lot of these ideas were developed during Obama’s second term when the idea was to mobilize the millions of idle workers. Just because you don’t have millions of idle workers doesn’t mean you can’t add jobs in the health and education sectors, but you need to shift them from some other sector. This is not really an idea that I’ve seen many progressives tackle, though Rebecca Gordon in The Nation did recently float the notion that maybe we don’t need a “24-hour economy.” And you could definitely imagine that. The world wouldn’t end if the CVS in my neighborhood were open 16 hours a day instead of 24 or if Chipotle closed at 8 p.m. instead of 10 p.m.

But I think the more likely candidate is full-service restaurants. That’s because restaurants with servers and bussers already compete fairly directly with fast-casual restaurants that serve food in a less labor-intensive manner. We know how to feed people with fewer workers, food service jobs are not particularly desirable, and even though full-service restaurants have a halo of quality around them, nothing about the table service aspect necessarily speaks to the quality of the meal. An America where a larger share of the population is working in the care economy is probably one where a smaller share is working in the foodservice economy. And that would plausibly be a change for the better.

And obviously we are not communists, so you don’t need to actually specify in detail where the labor is coming from. The market can work it out. But the fact remains that if you’re not starting with a very depressed economy, you can’t do a “new deal” and conjure labor out of idleness.

A walk on the supply side

And this is where I think the recent focus on trying to find increasingly exotic ways to tax increasingly narrow bands of hyper-wealthy people kind of falls down.

I do see the view, from a standpoint of abstract cosmic justice, that it’s annoying to see someone like Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos get so rich without contributing more to the Treasury. So there is a case for taxing wealth or unrealized capital gains or at a minimum changing the stepped-up basis rule. But fundamentally, I do think there are profound reasons why things like VAT and payroll taxes are the workhorses of European welfare states. Musk is not employing 10,000 butlers who can be taxed away and turned into preschool teachers. Inducing him to liquidate financial assets and fork over the proceeds does not generate any real resources that are available for new use. What a Nordic-style tax system does is broadly constrain consumption in order to free up resources for more extensive consumption of health, education, and other social goods.

You can achieve the same thing by taxing Musk’s unrealized capital gains and then using the proceeds to overbid the private sector for labor, leading to inflation. But it’s much sloppier and more chaotic than the European way. Besides this, if the problem with the European way is that it’s unpopular, well, it turns out that inflation is also unpopular. On some level, you can either sell people on the idea that the transformation is good or you can’t.

But the other way to go is just to reflect that we should probably have more emphasis on finding ways to expand the labor supply. Creating easier paths for foreign-trained doctors, dentists, and nurses to move to the United States and start practicing makes it much easier to provide expanded health care services. Instead of putting tariffs on imported solar panels because we want clean energy to “create jobs,” we could just let foreign manufacturers make the solar panels so we can get more clean energy without a massive reallocation of labor. And instead of celebrating the job-creating virtues of infrastructure spending, we could look to make our infrastructure work more cost-effective by improving productivity.

At the end of the day, the labor is a cost, not a benefit. So if you can come up with more cost-effective ways to do things (what if we had robot nannies that would make it possible to run high-quality daycare centers with lower staffing levels?), that’s good. After all these years of job-creation this and job-creation that, it’s hard to get your mind around making policy in a world of labor scarcity. But it’s actually kind of nice and everything makes more sense once you have a mindset of trying to reduce costs. And there’s no time like the present to get started.

"But I think the more likely candidate is full-service restaurants. That’s because restaurants with servers and bussers already compete fairly directly with fast-casual restaurants that serve food in a less labor-intensive manner. We know how to feed people with fewer workers, food service jobs are not particularly desirable, and even though full-service restaurants have a halo of quality around them, nothing about the table service aspect necessarily speaks to the quality of the meal. An America where a larger share of the population is working in the care economy is probably one where a smaller share is working in the foodservice economy. And that would plausibly be a change for the better."

I got out of restaurant management about 2.5 years ago after about 15 years in the trenches at your average casual dining chain, but my wife still works in them so I have a pretty good picture of what things are like both pre- and post-pandemic.

My take is that your average American chain restaurant is too damn big and closes too late. It was too big before COVID, and it's certainly too big now with so many sales dollars moving from dine-in to carry-out. Most casual dining chains could probably get away with being half as large as they currently are....chop off the parts of the restaurant that aren't the lounge/bar area, hire less servers and more to-go staff, and close an hour or two earlier. You'd still have space for folks wanting to dine-in, but you'd avoid those Mon-Thur nights when your restaurant is 2/3 empty at 6:30, but you don't want to send too many people home because you're still open for three and a half more hours.

The restaurant I managed was notoriously slow from 8-10 pm basically every night of the week....seldom was there a compelling reason to pay multiple employees to work for two extra hours, yet we were required to stay open until the posted time, because....duh. I was always told that closing that earlier (meaning, changing the posted hours, not doing it randomly) would scare customers off.

I think that COVID has challenged many assumptions about the sorts of tightly-held beliefs about the consumer that the people making decisions in certain sectors put forth as gospel, and it's a good time to re-evaluate some of those.

OMG guys we can edit comments now.