The most money goes where it matters the least

Presidential campaign donations are subject to diminishing marginal returns

Donations are rightly regarded as an important factor in a presidential election. They’re how campaigns hire staff, run get-out-the-vote operations, and, crucially, spend billions of dollars in ad buys.

That’s why it’s newsworthy — and quite alarming — to see a swell of right-wing tech billionaires pledge substantial sums of money to the Trump campaign and its associated political groups. Conversely, one reason (among many others) President Biden’s presidential campaign seems doomed is that his mega-donor operation has been driven into a state of paralysis by post-debate fears over his ability to win the election.

It’s true that campaigns need substantial funds to maintain operations. And it is certainly eye-popping to see individuals spend such outrageous sums of money on a political campaign. But I think we need to pump the brakes on how much we think this actually matters.

For presidential elections, particularly this presidential election, massive campaign donations are subject to diminishing returns.

That’s largely because the two candidates running for president are incredibly well-known, and seem to have incredibly calcified political support. While their campaigns and associated groups will be spending their money on a wide variety of functions, the most expensive and more important method of persuasion is advertising. And the relevant polling data and academic literature suggests that in elections like this one, it’s really just incredibly hard to change voter opinion.

How effective are presidential campaign ads, really?

The effectiveness of presidential campaign advertising is literally a multi-billion dollar question, and has been the subject of extensive research.1

The findings, as you might expect, are not entirely straightforward. But the basic story is that it requires very large amounts of aggregate campaign spending to move votes, in part because it’s hard to know what kinds of ads are going to be effective. Political obsessives often have strong and inaccurate intuitions about this, since the kinds of people who are persuadable via campaign ads are, almost by definition, quite different from the kinds of people who donate to candidates or obsessively follow out of state campaigns.

First, the aggregate. In 2021, the American Political Science Review published a study by John Sides, Lynn Vavreck, and Christopher Warshaw that compared election outcomes between 2000 and 2018 in areas where Democratic ads outnumbered Republican ads to outcomes in neighboring counties that saw comparatively fewer ads.2 They concluded that if a Democratic presidential candidate aired 100 more ads in a given television market over the final 64 days of an election compared to their opponent, they would gain a 0.018 percent increase in their support. The absolute maximum vote gain they could expect, even if they aired significantly more ads than their opponent, was 0.5 percent.

This is slim bang for the buck. But American elections have binary outcomes, so slim margins can make a big difference.

Yale political scientist Alexander Coppock led a study in the 2016 presidential election that analyzed a representative sample of 34,000 people who were shown a series of 59 randomized ad experiments. They found that not only are most ads fairly unpersuasive, the “weak effects are consistent irrespective of a number of factors, including an ad’s tone, timing, and it’s audience’s partisanship.” Overall, the impact on voters candidate preferences ended up being a measly 0.007 percent. It’s hard to persuade people to change their minds (just check out the comment section on any Slow Boring article), and people are instinctively skeptical of paid advertising.

That said, a more recent study Coppock worked on in 2024 suggests that with extensive testing, it is possible to identify certain ads that are far more (or less) effective than the average one.

The team looked at over 600 ads from 51 campaigns and outside groups in 2018 and 2020 and found that the best-performing ads had the potential to shift immediate vote preferences by 2.3 percentage points in 2018 down-ballot races, 1.2 percentage points in 2020 down-ballot races, and 0.8 percentage points in the 2020 presidential campaign. They also found that it is common for advertisements to be 50 percent less or 50 percent more persuasive than the average ad. But the researchers found that there were no consistent patterns for whether a certain type of advertisement (positive or negative) was more effective. The only way to figure it out is by testing it on a sample audience.

In his analysis of the study, Vox’s Eric Levitz writes:

Ad testing is very expensive. Not only do you need to hire consultancies that can assemble statistically significant survey pools, but you also need to pay to fully produce many ads that you don’t end up airing. And yet, according to the 2024 study, ads vary so much in their efficacy that campaigns would benefit from dedicating at least 10 percent of their media budgets to testing.

So old school political intuition is about as helpful as a screen door on a submarine. It looks like rigorous ad testing is the future.

The implications for 2024

I was curious how effective Professor Coppock thought ads would be in the 2024 election, given the fact that both Donald Trump and Joe Biden are incredibly well-known.

He told me, “If you’re predicting the effectiveness of the average ad in 2024, my guess is that it's having a positive but very small effect on vote choice.”

Thus far in the cycle, I think the polling data has largely proven that to be true.

Earlier this year, before the debate sent Democrats into an existential tizzy and the GOP began fantasizing about one of the largest electoral landslides of the 21st century, Trump was clinging to a small polling lead, and Biden was banking on his sizable cash advantage to close it.

Obviously, that did not happen.

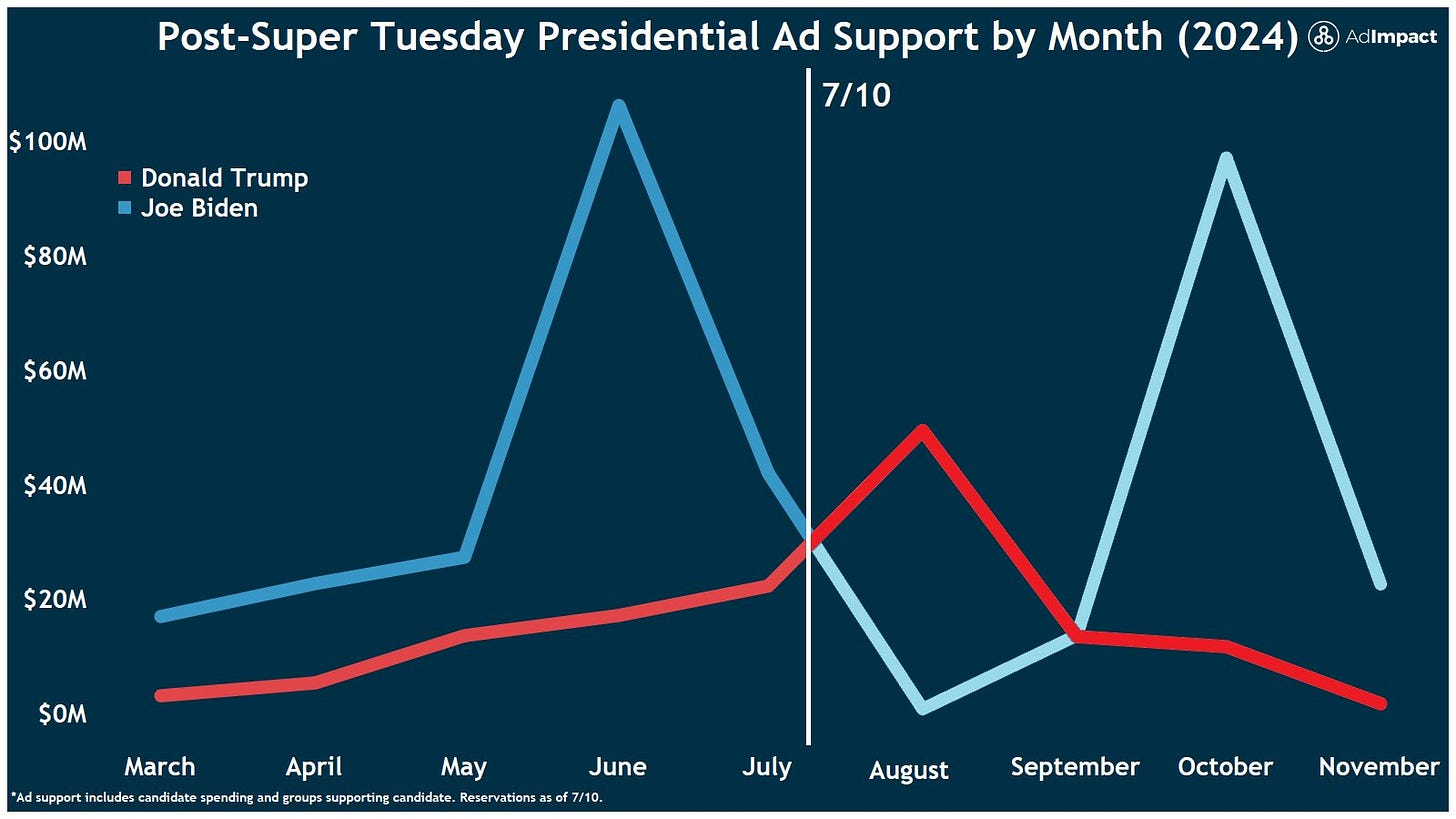

Starting in May, the Biden campaign and its associated political groups did massively outspend the Trump campaign. And by the end of June, right before the catastrophic debate performance made things even worse, his polls generally did not meaningfully improve.

I’m assuming the Biden campaign used rigorous ad testing to determine the efficacy of certain ads; this was just calcified political support in action.

The consensus seems to be, at the moment, that a new candidate will be taking over the Democratic ticket. So it’s worth noting that Coppock did say, while qualifying that it was speculation, that for a less-known candidate, “the average ad would have a bigger effect than the average ad for a Biden.”

Donald Trump is also quite a well-known political commodity, and despite the fact that he has amassed a significant campaign war chest (that has, in part been going to his legal bills), there’s little reason to believe it will substantially alter his position in the race.

When the aforementioned 2021 study reviewed some literature around political persuasion, authors Sides, Vavreck, and Warshaw summarized that “…when people have relevant prior attitudes, and especially strongly held attitudes, they are less likely to change their attitudes in response to new information.”

It’s fair to say that this applies, perhaps more so than any other presidential candidate in history, to Donald Trump. He attracts some of the most strongly held opinions of any contemporary politician. And while it’s clear that he’s gaining support among certain demographic groups, I doubt TV ads are the reason why.

Back in 2016, Hillary Clinton famously outspent Trump by a two-to-one margin. And Trump, even more famously, won the race.

I think this is largely because Trump was already an omnipresent figure in our media, and he frequently appears to voters in many forms that are not paid media. Perhaps his ad team will conduct a ton of ad testing and move the needle by an exceedingly small margin and swing certain battleground states. It’s hard to be sure. But the polls show that he’s going to win those states by a margin that is outside the reach of even the best performing ads. And his exceptional level of press coverage will compete with any carefully curated ad that his campaign might deploy. As a result, I think his swell of new mega-donors might be better off contributing their sizable fortunes to other candidates.

Money is better spent down-ballot

I am not personally interested in advancing the project of right-wing politics in the United States, but if I was, and I had few billion to spend, I’d probably put it towards down-ballot races.

As we’ve seen in each study, the effect of advertisements are small, but they are notably higher in non-presidential races. Sides and his co-authors spell out the logic, explaining, “This pattern suggests more potential for persuasion in down-ballot races, where people have thought less about the candidates and have fewer stored considerations and weaker affective tags, if any.”

In the 2024 cycle, there are incredibly important Senate and House races in which Democrats have a considerable cash advantage. This is largely driven by the fact that individual campaign contributions are limited, and Republicans’ small dollar donor operations generally fare worse than Democrats’. And the spending by outside political groups (where donors face fewer restrictions) on these races isn’t large enough to help Republicans make up the sizable cash discrepancies.

In Wisconsin, the GOP candidate is a wealthy real estate mogul named Eric Hovde who seems to have primarily lived his adult life in California. Despite plowing $8 million into his campaign, Hovde is being outraised by a nearly two-to-one margin by incumbent Tammy Baldwin. I’m sure his associated political groups wouldn’t mind $10 million from a tech CEO with recently discovered right-wing politics.

The margins are even higher in other critical races. In Ohio, Senator Sherrod Brown has raised nearly $36 million more than his opponent Bernie Moreno. In Montana, Senator Jon Tester has maintained a similar advantage over his opponent. And while it’s even less-sexy, Democrats are holding cash advantages in the swing districts of NY-03, VA-07, and CO-03.

The majority in the House and Senate could very well come down to those elections, which in turn, will decide the fate of Trump’s second term legislative agenda. Perhaps boosting Trump’s image will trickle down to the candidates in those races. Or, perhaps mega-donors are on the brink of writing some massive down-ballot checks right now, and we just haven’t heard about it yet.3

Or, and I think this is most likely, I’m just missing the point here.

Campaign donations are primarily used to help candidates win elections. But they’re also signals. Some of these mega-donors might be looking to ingratiate themselves with a future Trump administration, and don’t actually care whether Eric Hovde wins his Wisconsin Senate race or scurries back to his Orange County mansion.

Ultimately, these donors probably don’t care how the money is spent, it matters more that everyone knows that they spent it.

The exact methodology here is worth looking at if you’re interested

Imagine how cooked we would be as a society if political ads were super effective. The vast majority of people tuning out political advertising is so much better than the alternative.

"President Biden’s... mega-donor operation has been driven into a state of paralysis...."

I'm not a mega-donor, or even a micro-donor, more on the pico-donor scale, but I can tell you that I am not suffering paralysis.

I am delaying my donation until after the convention. If Biden is still the nominee, then I'll give what I can, because anything is better than Trump. If (as I hope) Harris is the nominee, then I'll give what I can in order to signal a burst of enthusiasm, or at least a pico-burst, which perhaps in combination with other donors will look like a burst of enthusiasm at the national scale.

Until then, I'm keeping my powder dry. Not paralysis, just an attempt at strategic timing.

Updated on July 22, after Harris is clearly the nominee: I have now dropped a considerable sum, several pico-trillions, on a donation to the Harris campaign. The first 24 hours after Biden's announcement are going to break records, and I'm happy that I waited to be a part of that.